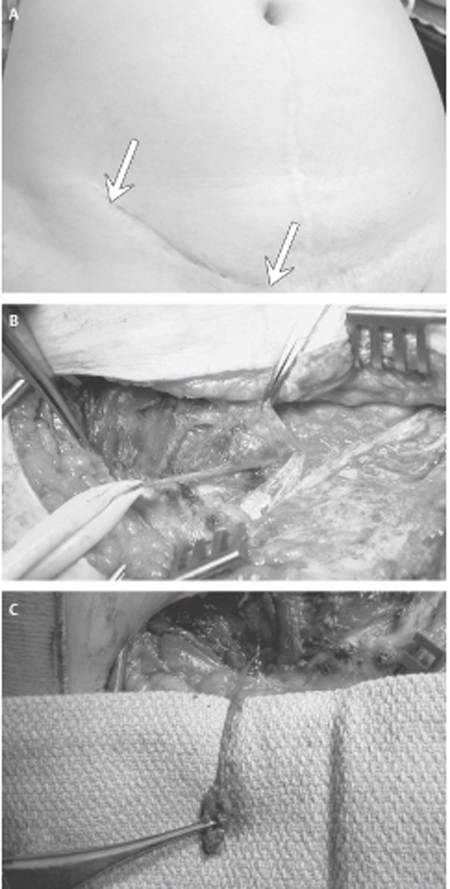

35 Ilioinguinal/Iliohypogastric Neuropathy There is no “typical” case history, though the following illustrates some of the difficulties experienced by both patient and physician in dealing with this entity. A 31-year-old woman developed intermittent right lower quadrant pain following a miscarriage. Three years later, a right inguinal hernia was repaired and the symptoms subsided. The hernia recurred 5 months later following childbirth. The hernia was repaired again a year later, and at the same time the ilioinguinal nerve was explored and scar tissue removed. Her pain was not relieved but progressed in severity and radiated to the anteromedial thigh and sometimes to the posterior superior iliac spine. There was constant discomfort but, at times, the pain was sharp and she graded it as 8 out of 10 on the visual analog scale. The severe pain was precipitated by coitus, and she was unable to lie supine without flexing her hips. Assessment by three gynecologists, two laparoscopic examinations, abdominal ultrasound, barium enema, and colonoscopy showed no abnormalities. Five years after the second hernia surgery the patient presented to us with ongoing severe pain. Several medications had failed to provide significant benefit. Examination demonstrated focal tenderness medial to the anterior superior iliac spine and at the external inguinal ring (Fig. 35–1, arrows ), mild hyperalgesia in the ilioinguinal dermatome, and restriction of back extension and left lateral bending due to right lower quadrant pain. Two ilioinguinal nerve blocks relieved the pain on each occasion. The inguinal region was explored and the ilioinguinal nerve was found to be invested in dense scar tissue, necessitating removal of a 5 cm length of the nerve (Fig. 35–1 B,C). The patient did well for 6 months, but the pain recurred and began to interfere seriously with her life. Paravertebral blocks of the T11, T12, and L1 nerve roots relieved her pain and, a year after her neurectomy, microsurgical dorsal root ganglionectomies of T11, T12, and L1 were done. The patient resumed her normal activities and remained pain free 5 years later. Ilioinguinal and iliohypogastric neuropathy Figure 35–1 (A) The right groin scar from prior inguinal hernia surgery is shown, including the areas in the scar that are exquisitely tender to touch (arrows). (B) At surgery, the ilioinguinal nerve (Penrose drain) is identified heading into an area near the external inguinal ring where it is heavily invested in scar from prior operation. (C) The neuroma at the end of the scarred nerve is shown. The neuroma and proximal nerve were resected, with the proximal stump allowed to retract into and deep to the abdominal wall musculature The cutaneous branches of the lumbar plexus give rise to the iliohypogastric, ilioinguinal, and genitofemoral nerves, the lateral femoral cutaneous nerve of the thigh, and the obturator nerves. The iliohypogastric is a motor and sensory nerve arising from the T11, T12, and L1 nerve roots. It emerges from behind the lateral edge of the psoas muscle and pierces the transversus abdominis muscle above the iliac crest. Its anterior branch runs forward between the internal oblique muscle and the external oblique aponeurosis, which it penetrates to supply the skin above the pubis. Its posterior branch supplies an area of the buttock just posterior to the iliac crest. The ilioinguinal nerve is also a mixed nerve arising primarily from L1 but also receiving branches from T12 that emerge behind the psoas muscle below the iliohypogastric nerve. It passes obliquely across the quadratus lumborum and iliac muscles and perforates the transverse abdominal and internal oblique muscles medial to the anterior superior iliac crest. It runs along the inguinal canal and emerges through the external ring. It provides sensation to the upper medial aspect of the thigh and the base of the scrotum and labia. In several hundred cases studied by Moossman, a “normal” course of the ilioinguinal nerve was seen in only 60%, with the remainder having the ilioinguinal nerve as a branch of the iliohypogastric or genitofemoral nerves. The genitofemoral nerve arises from L1 and L2 and consists mainly of sensory fibers with a motor branch to the cremasteric muscle (efferent component of the cremasteric reflex). It travels obliquely through and over the psoas muscle, emerging in the retroperitoneal space opposite the L4 vertebral body. It divides into the genital (external spermatic) and femoral (lumboinguinal) branches, which travel separately behind the ureter and across the base of the broad ligament. The genital branch crosses the lower end of the external iliac artery and enters the inguinal canal through the internal ring. It follows the spermatic cord or round ligament and supplies sensation to the scrotum or labia and medial upper thigh. The femoral branches descend lateral to the external iliac artery behind the inguinal ligament; passing through the fascia lata, they enter the femoral sheath where they lie lateral to the femoral artery. These branches supply sensation to the upper anterior thigh. Ilioinguinal and iliohypogastric neuralgia and entrapment may occur spontaneously, as a result of congenital bands. More frequently it is seen as a complication from operations on the lower abdominal wall and inguinal region (Table 35–1)

Case Presentation

Case Presentation

Diagnosis

Diagnosis

Anatomy

Anatomy

Characteristic Clinical Presentation

Characteristic Clinical Presentation

| 1 | Inguinal hernias or postherniorrhaphy |

| 2 | Previous abdominal surgery |

| a. Appendectomy (McBurney incision) | |

| b. Gynecological (Pfannenstiel incision) | |

| c. Retroperitoneal | |

| 3 | Congenital tendinous bands |

The ilioinguinal clinical triad includes the following:

- Pain—sharp, stabbing, or aching and burning, in the groin with radiation to the pubic tubercle and proximal inner thigh

- Sensory abnormalities–hypesthesia, hyperalgesia, or allodynia in the ilioinguinal dermatome

- A circumscribed trigger point medial to and below the anterior superior iliac spine, where pressure reproduces the characteristic pain radiation

Iliohypogastric pain is distributed above the pubis, and the point of maximum tenderness is often above the midpoint of the inguinal ligament. Genitofemoral pain is more medial than ilioinguinal pain, and the point of maximum tenderness is at the pubic tubercle or external inguinal ring. Distinguishing genitofemoral neuralgia from ilioinguinal neuralgia can be difficult and at times impossible.

Differential Diagnosis

Differential Diagnosis

Pain in the groin region has a wide differential diagnosis, including visceral origin from hernias or other bowel problems, pelvic and urological pathology, musculoskeletal disorders in the hip joint, and vascular pathology.

The ilioinguinal, iliohypogastric nerves can be entrapped following appendectomies, blunt trauma, or urological and pelvic operations as well as inguinal herniorrhaphies.

Persistent pain following inguinal hernia repairs is a significant problem. Marsden reported a series of 939 inguinal hernia repairs in which 2.8% of patients still suffered significant wound pain at 1 year and 1.4% were substantially disabled at 3 years. Some of these failed cases likely represent an initial misdiagnosis, where ilioinguinal entrapment was the true diagnosis. More frequently, entrapment of the ilioinguinal or the iliohypogastric nerves may be caused by suture placement, tendinous bands, fibrous or mesh adhesions, or neuroma formation from nerve injury. Ongoing pain or a new onset of pain (especially neuralgic) following inguinal hernia surgery should alert the clinician to the possibility of injury or persisting entrapment of the ilioinguinal and/or iliohypogastric nerves. A careful history and clinical exam, aided by appropriate nerve blocks, often allows the diagnosis to be made.

Diagnostic Tests

Diagnostic Tests

Unfortunately, electrical and imaging tests are not useful in elucidating the diagnosis of iliohypogastric and ilioinguinal neuropathy. If suspected on clinical grounds, local blocks of the ilioinguinal–iliohypogastric nerves with bupivacaine (or another local anesthetic with an intermediate duration of action) at the trigger point medial to the anterior superior iliac spine help confirm the diagnosis. A similar block of the genitofemoral nerve at the external ring may help to differentiate between these two neuralgias. The addition of steroids does not produce prolongation of pain relief. Differential paravertebral blocks of the T11, T12, L1, and L2 nerve roots are also useful in some patients to substantiate the neuropathic nature of the pain.

Management Options

Management Options

The initial approach may be conservative, using one or a combination of physical modalities, psychotherapy, and pharmacotherapy. Many of these patients have already visited a pain clinic and been treated with various medications. If not, a course of tricyclic agents is worthwhile, such as amitriptyline or nortriptyline. Other medications that may be beneficial include anticonvulsant agents such as carbamazepine (Tegretol, Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corp., East Hanover, NJ) and gabapentin (Neurontin, Pfizer, Inc., New York, NY).

For those patients with an obviously painful or entrapped ilioinguinal or iliohypogastric nerve, especially where a nerve block has been successful in ameliorating pain, a peripheral nerve surgical procedure is warranted. Intraoperative management is dictated by the findings at surgery, with the two main options being neurolysis or neurectomy.

Surgical Treatment

Surgical Treatment

Decompression or Neurolysis

The inguinal area was explored by means of an incision beginning superior and medial to the anterior superior iliac spine, extending parallel to the inguinal ligament, and ending at the pubic tubercle. The external oblique aponeurosis was opened parallel to its fibers down to the external inguinal ring. The ilioinguinal and iliohypogastric nerves were identified and dissected along their courses from the internal oblique to the external ring and rectus sheath, respectively. There was considerable anatomical variability in the course of these nerves. If the nerve was obviously entrapped by tendinous bands at the point of exit from the internal oblique muscle a decompression or neurolysis was done.

Successful pain relief was achieved in 34% of patients, whereas 50% of cases were failures and 16% were lost to follow-up. Three of these patients required repair of an unsuspected direct hernia at the time of surgery.

Neurectomy

Neurectomy was done in patients who had failed decompression or where previous surgery had invested the nerve in extensive scarring.

Successful pain relief was obtained in 60% of patients, failures were observed in 38%, and one patient was lost to follow-up.

Dorsal Root Ganglionectomy

This procedure was offered to the remaining patients who failed the foregoing procedures (˜20% of initial total), and demonstrated good relief of pain from paravertebral blocks. The microsurgical resection of the sensory components of T11, T12, and L1 nerve roots was done through a paraspinal muscle-splitting incision ˜1 cm lateral to the lateral portion of the intervertebral foramina. Permanent anesthesia in the groin area was produced, but in four patients it was subsequently necessary to extend the ganglionectomies up to T9 and T10 or down to L2. The success rate was 50%, whereas failure to produce pain relief was observed in 30%. Twenty percent of patients were lost to follow-up.

Discussion

Discussion

Neurolysis carries the benefit of preservation of sensory function (if, in fact, this is retained postinjury). Neurolysis appears to achieve reasonable results where the nerve is primarily entrapped and not injured, as demonstrated in about one third of the patients in this series. However, the results of neurolysis appear to be poor for long-term pain control in over half the patients. This is similar to the generally poor results of neurolysis for cutaneous nerve injuries that result in painful neuromas. In circumstances of excessive nerve scarring and painful neuroma, a neurolysis procedure is probably doomed to failure. The most reliable procedure remains a neurectomy. The patient must accept the trade-off: loss of sensory function for probable relief of pain. Because the ilioinguinal and iliohypogastric nerves do not supply sensation to a critical area, the sensory deficit is well tolerated. Modulation via electrical stimulation (see Chapter 57) is emerging as a promising avenue to managing painful nerve injuries.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree