Chapter 9 Readers of this chapter will be able to do the following: 1. Discuss intervention policy issues at the developing language level. 2. Describe intervention goals appropriate for developing language. 3. List a range of intervention procedures with an evidence base in the developing language period. 4. Discuss the SLP’s role in developing emergent literacy skills. 5. Describe various contexts and models of service provision at the developing language level. 6. Discuss intervention issues and strategies for older clients with severe impairment who function at the developing language level. 7. Describe interventions aimed at improving communication and social integration for children with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) at the developing language level. We talked in Chapters 6 and 7 about the reauthorized Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA) of 2004, the federal law that mandates free, appropriate public education (FAPE) to all children with handicaps. Part B of IDEA is concerned with school-age children, but its mandate extends to 3- to 5-year-olds as well. We talked about using the Individual Family Service Plan (IFSP) mandated under IDEA to plan intervention services for infants, toddlers, and their families. Educational plans for preschoolers and for older children with disabilities who function at DL levels, however, may be written in a somewhat different format. This format is the Individual Educational Program (IEP). IEPs differ from IFSPs in several ways. The content and format are somewhat dissimilar. The biggest difference is that the focus of the IEP is on the child, rather than on the family. IEPs do not by any means leave the family out of the picture, though. IDEA has some very specific requirements about how families participate in the process of developing an IEP. The family is considered central members of the IEP team. They must be notified of an IEP meeting with sufficient time for them to arrange to attend. The meeting must be at a time that is convenient for both educational staff and parents. The parents have the right to accept or reject the IEP and to request that modifications be made to it. They also must approve the plan being proposed for the child before any program is initiated. A sample IEP format is provided in Appendix 12-1. The best practice for all our clients is family-centered; this is especially true for young children. Does this mean that family members must deliver the intervention? Not necessarily. As we discussed in Chapter 7 when we talked about intervention for emerging language, we need to remember that every family is different. For some families, having parents be primary agents of intervention makes sense. In these families, parents may feel they want to be centrally involved in their child’s program, that they have the time and energy to devote to delivering the intervention, and that they are comfortable with the shift in role from parent to teacher. A second issue in family-centered intervention involves the extent to which families are involved in the choice of intervention goals and methods. As we discussed in Chapter 3, for most clients there are more potential goals than there is intervention time to achieve them. This means we must pick and choose among the potential targets. In Chapter 3, we talked about some criteria to use in making this selection, such as teachability, functionality, and so on. Another factor to be considered, though, is family preference. Families are very likely to have feelings and opinions about areas in which they would like their child to show improvement. This information is an important part of the intervention planning process. We have an obligation, in family-centered practice, both to elicit this information from parents and to take it seriously in devising the intervention program. In Chapter 3, we talked about three aspects of intervention that McLean (1989) suggested we consider when designing a management plan for a child with a language disorder: the products, or intended goals of the intervention; the processes, or methods used to achieve these goals; and the context, or physical and social milieu in which the intervention takes place. Let’s look at each of these aspects of the intervention program and see how they apply to children in the DL phase. For many children who, like Rachel, are within or only a few years beyond the preschool period chronologically, goals of intervention include some of the forms and functions acquired by typical children between 3 and 5 years of age. Some special considerations are involved in planning intervention programs for older, severely impaired clients still in the DL phase, which we will discuss later. In general, though, the goals for language intervention in this phase are to help the child acquire intelligible, grammatical, flexible forms of expression for the ideas and concepts the child has in mind, to enable the child to understand others, to give the child the tools to make communication effective, efficient, and rewarding so that social interaction proceeds as normally as possible, and to strengthen the oral language basis for success in literacy. As we discussed in the previous chapter, the preschool years are normally a period of exponential language growth, when children with typical development move from mean lengths of utterance of less than two words to more than five. Another way to describe this period is to say it is the interval between Brown’s (1973) stages II and V+, the period of the acquisition of basic structures, functions, and meanings of the language. Table 9-1 reviews some of the major changes that take place in the language of normally developing children during the preschool years. These milestones provide a basis for establishing the goals of intervention at the DL level. Table 9-1 Milestones of Normal Communicative Development: Preschool Years One thing you will probably notice right away about the list in Table 9-1: it’s long. Not every child with DL will achieve everything on this list during the intervention period. As always, we will have to choose intervention goals judiciously. Knowing the normal sequence of acquisition is necessary to make these decisions, but it is not enough. Other considerations, such as those discussed in Chapter 3 and those we just talked about in terms of family involvement, must come into play. Later we’ll talk more about the issue of choosing intervention goals for the older, severely impaired client. Let’s look now at each of the major areas of intervention goals for children with DL and discuss some of the considerations necessary to establish individual targets in each one. We talked in the previous chapter about how to decide when and how to assess phonological production. In general, children at developing levels of language are not candidates for speech sound intervention unless their intelligibility is significantly impaired. Because so much phonological growth is going on in the DL period, intervention for particular sounds can usually be deferred until school age, since many speech sound problems resolve on their own by then (Shriberg & Kwiatkowski, 1994). However, if a child is seriously unintelligible, intervention is warranted. Social disvalue and even social isolation, as well as frustration and behavioral and emotional reactions, can occur in children who have difficulty in getting messages across, even if they would eventually outgrow the unintelligibility. Although the specific targets of the intervention in this area will be the acquisition of particular sounds or the suppression of particular simplification processes, we need to remember that the important long-term goal is to increase the client’s overall intelligibility. All the issues we discussed in Chapter 3 about being careful to ensure that behaviors learned in intervention generalize to real conversation must be addressed to ensure that phonological production improvement leads to real gains in intelligibility. Kent, Miolo, and Bloedel (1994); Gordon-Brannan and Hodson (2000); and Morris, Wilcox, and Schooling (1995); discussed a variety of instruments that can be used to evaluate changes in intelligibility in the course of an intervention program. Although the range of approaches to speech sound intervention is beyond the scope of this text, Williams, McLeod, and McCauley (2010) provide a comprehensive description and evaluation of the bases in evidence of a large number of interventions in this area, categorizing them into three major groups: interventions that focus specifically on speech sound production but assume that errors stem from phonological, rather than motoric sources; interventions that place speech sound production in the broader context of speech perception, language, literacy, and communication; or those that focus primarily on the motor acts involved in speech production. We need to remember, too, that speech sound and language disorders often co-exist in the same child (Pennington & Bishop, 2009). So assessing syntactic and semantic skills in unintelligible children is always important in order to avoid missing deficits in these areas that are masked by the difficulty in understanding what the client says. When assessment of an unintelligible child indicates that syntactic and semantic deficits are present, it makes sense to address those targets early in the intervention program, rather than waiting until the child is fully intelligible. One way to address them is through input, providing indirect language stimulation, focused stimulation, or auditory bombardment (see Comprehension versus Production Targets, later in the chapter) of the forms we want the child to begin learning. These activities can be supplemented with more direct production activities that control for pronounceability of target words. In general, in accordance with our principle of requiring the client to do only one new thing at a time, we will want to address phonological and semantic/syntactic targets separately, not within the same activity. However, Tyler, Lewis, Haskill, and Tolbert (2002, 2003) showed that, when children have both phonological and morphosyntactic deficits, working on morphosyntax leads to changes in both areas. This research suggests that, for children with both speech and language problems, morphosyntactic deficits should be addressed first, followed by work on whatever phonological targets have not resolved in the course of the first segment of intervention. One further consideration in planning phonological intervention at the preschool level concerns the connection between phonology and metaphonology. Metaphonology, or phonological awareness (PA), is the ability to detect rhyme and alliteration; to segment words into smaller units, such as syllables and phonemes; to synthesize separated phonemes into words; and to understand that words are made up of sounds that can be represented by written symbols or letters. These PA skills develop sequentially through the late preschool period (Hodson, 1994; Swank, 1999; Schuele & Boudreau, 2008). Several of these abilities have been shown to be closely related to success in learning to read (Hogan, Catts, & Little, 2005; Scarborough, 2003; Swank, 1994, 1999) and spell (Bourassa & Treiman, 2001; Clarke-Klein & Hodson, 1995; Gillon, 2002; Kirk & Gillon, 2007). Bird et al. (1995), Larrivee and Catts (1999), Pennington and Bishop (2009), and Rvachew et al. (2003) have shown that children with productive phonological problems during the DL period sometimes have trouble acquiring PA and are at risk for developing reading problems. This information suggests that when working with preschoolers who have phonological production problems, incorporating PA activities within the speech therapy may be helpful in preventing literacy difficulties. A few studies have shown that doing so does improve both speech and PA in children with speech delays (e.g., Hesketh, Adams, Nightingale, & Hall, 2000; Kirk & Gillon, 2007; Van Kleeck, Gillam, & McFadden, 1998). Hesketh (2010) summarizes this literature, concluding that children as young as 4 can be taught PA, that PA instruction improves literacy performance especially when alphabet letters are taught as well, and that including PA in a speech program leads to as much improvement in speech as is seen when the focus is speech only. Since incorporating PA activities in speech therapy may help shore up preliteracy weakness in children with speech sound disorders, clinicians can consider including PA activities in speech intervention for preschool children with reduced intelligibility. Some suggestions for doing this appear in Box 9-1. Kiewel and Claeys (1999) and Noble-Sanderson (1993) also provided phonology programs built around storybook activities that integrate speech sound remediation with the development of PA for children at the DL level. Children with developmental language disorders (DLD) appear to acquire words in comprehension much the way typically developing children do, but may need to hear a new word twice as many times as other children before comprehending and independently using the new word (Gray, 2003; Rice, Buhr, & Oetting, 1992). Children with language impairments also have particular difficulty in the acquisition of words to talk about cognitive states, like thinking (Lee & Rescorla, 2008), with verb vocabulary (Loeb, Pye, Redmond, & Richardson, 1996) as well as the use of verb particles (pick up, put down, etc.) (Watkins, 1994). In addition, children with DLD are less able to identify semantic features than their peers with normal language. These findings suggest that children with DLD have broader difficulties with receptive vocabulary than simply a reduced ability to acquire labels; they may need enriched input with repeated opportunities to see connections between words and their referents in order to learn new lexical items. Gray (2005) found that providing both semantic and phonological cues aided learning new words by preschoolers with DLD. This suggests that as we introduce new vocabulary, it makes sense to highlight both semantic (“triangle is the name of this shape; it’s a shape that has three sides; a piece of pizza is shaped like a triangle”) and phonological (“triangles have three sides and tri an gle has three parts; triangle starts with the same sound as toy) aspects of the word. Owens (2004) provided a list of likely vocabulary targets for the DL period. These appear in Appendix 9-1. But Neuman and Dwyer (2009) point out that, because of the known relationship between complexity of vocabulary in preschool and reading achievement as much as 2 years later, it is important not only to teach basic words, but to expose students to rare words, as well. Ruston & Schwanenflugel (2010) showed that conversational input from an adult emphasizing use of rare words, linguistic recasts,and open-ended questions increased expressive vocabulary in children with low levels of vocabulary development. Paul (2011) gives guidelines for providing this kind of enriched input. These techniques can be important not only for preschoolers with DLD, but also for children who have impoverished vocabularies for other reasons, such as limited English proficiency, as well. You’ll notice from the list in Table 9-1 that this area contains targets not only in vocabulary, which is, of course, important, but also in the kinds of semantic relations conveyed within and between clauses of sentences. In the early DL phase, an important goal of intervention is helping children broaden the range of ideas they can talk about. Toward the end of this phase, we want to help clients make their sentences more efficient by combining ideas, or propositions, within a sentence to convey specific semantic relations between clauses. Assessment information collected during the standardized and informal portions of the evaluation should guide us toward the level of semantic complexity to target within the client’s language. Remember that, when we’re planning targets and methods of intervention for language, we artificially segment language into components such as semantics and syntax. But really, when we target a particular sentence type, that sentence is, of course, conveying a meaning. Similarly, when we target a particular meaning for expression, that expression takes a syntactic form. So in practice it is hard to separate the semantic and syntactic components of sentences. When we plan intervention targets and activities involving semantic and syntactic expression in sentences, the main thing to remember is the principle we talked about in Chapter 3: only one new thing at a time. When asking a child to produce a more complex sentence form, we want to be sure it encodes a meaning that the child has already expressed in a simpler way. When asking the child to talk about a new meaning or combine new meanings in sentences, we need to control for syntactic complexity, making sure that the form we want the client to use in producing this new meaning is already within the production repertoire. Bound morphemes are particularly difficult for children with language problems of a variety of etiologies (Goffman & Leonard, 2000; Leonard, 1997; Rice, Warren, & Betz, 2005; Rice & Wexler, 1996). Auxiliary verbs and small, closed-class morphemes, such as articles (a, an, the) and pronouns (e.g., I, you, he, she, we they), also seem to cause particular difficulties for children with language impairments (Bates, 2003; Beverly & Williams, 2004; Eisenberg, 2005; Rice, Warren, & Betz, 2005). Irregular past morphemes and use of –ing endings seem to be a relative strength (Redmond & Rice, 2001; Rice, Warren, & Betz, 2005). Studies of children with slow expressive-language development as toddlers who show chronic delays through the preschool years (Paul & Riback, 1993; Rescorla & Roberts, 2002) substantiate this pattern. Difficulties with the elaboration of sentences through complex sentence production have also been reported (Eisenberg, 2005; Thordardottir & Weismer, 2001). It would appear, then, that verb marking with auxiliaries and inflections, closed-class morphemes, pronoun use, and the acquisition of complex sentences are areas in which children with language disorders can be expected to show particular difficulties during the DL period. These areas would be especially appropriate targets for intervention, when, of course, these deficits are documented by the assessment process. Fey, Long, and Finestack (2003) discuss some guiding principles for selecting goals for syntax and morphology during the DL phase. These are summarized in Table 9-2. Table 9-2 Principles of Goal Selection for Grammatical Targets in the Developing Language Period Adapted from Fey, M., Long, S., & Finestack, L. (2003). Ten principles of grammar facilitation for children with specific language impairments. American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 12, 3-15. We talked in Chapter 3 about the issue of targeting comprehension as opposed to production in the intervention program. There we said that, when assessment indicates a form or meaning is comprehended but not produced, production training is indicated. Lahey (1988) emphasized the fact that equivalent comprehension and production responses are often not present in normal language learners. She argued that a child should be exposed, through multiple meaningful exemplars in the input language, to forms and meanings that are not in the comprehension repertoire. But she concluded that comprehension responses, such as pointing to contrastive stimuli, do not need to be trained before production of the forms is targeted. Guided production activities appear to facilitate both comprehension and production of new meanings and forms in children. Recall, too, that Chapter 3 included some suggestions about targeting comprehension versus production performance in the intervention program. Production training should be a high priority for forms and meanings for which the child demonstrates comprehension. For forms and meanings that the child does not yet appear to comprehend but that are chosen as intervention targets on the basis of other considerations we’ve discussed, an input component should be part of the intervention plan. This might include focused stimulation or indirect language stimulation activities that provide multiple opportunities for the clinician to demonstrate use of the structure in context. Auditory bombardment is another viable input option. Hodson and Paden (1991) advocated using this approach to facilitate phonological development. They argued that phonological skills are acquired, at least in part, by listening. This implies that children need to listen carefully and often to the sounds they are being asked to produce. Kouri (2005) showed that, in a vocabulary training program, auditory bombardment had effects comparable to an elicited imitation program on the use of target words in real communication. Hodson and Paden suggested having children listen to a list of target words. It is worth noting that Flexer and Savage (1993) showed that both children with language impairments and those with normal hearing showed improved attention when assistive listening devices were used to improve signal-to-noise ratios during a testing situation. There is, then, some evidence that these devices might be useful in auditory bombardment activities for children with language needs. In auditory bombardment activities, the child simply sits and plays quietly with nondistracting material such as Play-Doh as the clinician reads the list of words. Although traditional auditory bombardment uses simply a list, it might, alternatively, consist of listening to a story that contains numerous examples of target forms. Hoffman, Schuckers, and Daniloff (1989) provided poems and stories that are weighted with examples of phonological targets. Cleave and Fey (1997) discussed the development of “syntax stories” created to provide auditory bombardment of particular target forms within a story context. Box 9-2 gives an example of an excerpt from one of their “syntax stories.” Regardless of whether a list or a story is read, the auditory bombardment segment generally makes up about 5 minutes of the intervention session. The child is not required to perform any discrimination activities, only to listen. Such activities also make excellent “homework” assignments for families interested in working on targets at home. They can easily be substituted for the child’s usual bedtime story and don’t require the parents to judge or correct the child’s communication. If follow-up activities, such as illustrating the clinician’s “syntax story” and rereading it with cloze procedures, are added, as Cleave and Fey suggest, even more benefit can be derived from the auditory bombardment. A better way to incorporate pragmatics in the intervention program, in our view, is the method advocated by Craig (1983) and Marton (2005). They argued that, rather than defining pragmatics as an additional set of rules that the child needs to learn, we are wiser to see pragmatics as the context in which intervention takes place, and to make sure that each new form learned is practiced in a variety of pragmatic contexts. That is, rather than teaching turn-taking as a separate skill, we would develop activities in which the client could take turns with the clinician using a linguistic form that was a target of intervention. Or, instead of teaching topic maintenance as a separate skill, we would give the client an opportunity to talk about a topic of interest for an extended number of turns, using newly acquired forms. We could, for example, ask a client who is working on past-tense forms to describe each step used to, make the pudding now being shared with a parent who was not present during its preparation. If the child strays from the topic, the clinician could provide a prompt to return to describing the sequence, such as, “Wait a minute, weren’t you saying how we made the pudding? ‘We stirred the milk,’ you said. Then what happened?” Must these pragmatic contexts be present in every intervention activity? We don’t think so. In fact, in our view they should not be, because that would lead us to violate Slobin’s (1973) principle of one new thing at a time. If past-tense forms are just being elicited, we won’t want to ask the child to use these new forms to fulfill a new function such as maintaining a topic—not until the new form has been somewhat stabilized. A more reasonable approach, to our way of thinking, is to incorporate pragmatic contexts into the intervention plan for every objective, but not for every activity. Some activities should be devoid of pragmatic context, to allow the child to focus attention on the linguistic objectives. Other activities can be designed to help clients use the new structures in real pragmatic contexts. The real communicative contexts chosen should be based on the pragmatic assessment data. Suppose Rachel, for example, had been evaluated with Prutting and Kirchner’s (1983) Pragmatic Protocol and had been found to have deficits in conversational repair. Once appropriate question forms had been added to her repertoire by means of semantic and syntactic intervention, these forms might be put to use in the context of conversational repair. The clinician might feign misunderstanding of something Rachel said, model asking a clarification question, and encourage Rachel to answer it to repair the breakdown. The clinician might then give a mumbled or otherwise unclear message and encourage Rachel to ask a question to get clarification. In this way the client can be helped to use new semantic and syntactic forms in pragmatic contexts identified as problem areas as a result of the pragmatic assessment. Brinton and Fujiki (1989, 1995) provided detailed procedures for this aspect of intervention. A variety of studies (summarized by DeKroon, Kyte, & Johnson, 2002; Johnston, 1994; Leonard, 1997; Mainela-Arnold, Evans, & Alibali, 2006; Rescorla & Goossens, 1992) have shown that children with language problems perform less well than normally speaking peers on a variety of cognitive tasks, including symbolic play, even when they score within the normal range on nonverbal intelligence tests. During the preschool period in normal development, as Vygotsky (1962) pointed out, language begins to help to structure thought, and thought is carried out primarily in the modality of language. One of the major accomplishments of normally developing children in the preschool period is the beginning of the integration of language and cognitive processes, each feeding off and growing out of the accomplishments of the other. Much learning about concepts, categories, and the physical world during the preschool years goes on through the medium of language, instead of through direct perception and experience, as it did in the sensorimotor period. Children structure symbolic play through language both when they play alone (often talking out loud to pretend playthings) and when they play with peers (often negotiating the roles and rules of the play by talking about them: “I’ll be the baby and you be the mommy, but be a nice mommy and don’t scold me when I spill my bottle.”). It should not be surprising, then, that children with language problems would begin to lag behind in some of these skills that are so intertwined with language. Many preschoolers with language delays develop problems in learning to read and write, even when their oral language problems appear to resolve (Skibbe et al., 2008; Stothard, Snowling, Bishop, Chipchase, & Kaplan, 1998). Research reviewed in the National Joint Committee on Learning Disabilities (2007) Technical Report 12, Learning Disabilities and Young Children: Identification and Intervention, has shown that deficits in phonological processing can be a major obstacle in learning to read. This research suggests that strong oral language, phonological awareness, understanding about print, alphabet knowledge, invented spelling, rapid naming, and a child’s ability to write his or her own name prior to kindergarten are all indicators of literacy success in school (National Early Literacy Panel, 2005). And research has shown that the most effective interventions for children at risk for later reading problems focus on oral language instruction in preschool and kindergarten, and include explicit teaching of phonemic awareness, letter-sound relationships, vocabulary, and language comprehension (Dickinson, McCabe, & Essex, 2006; Lyon, 1999). Increasingly, and for good reason, speech-language pathologists are being expected to address these areas of instruction in preschool programs for children at risk, and to promote preliteracy development in these children (American Speech-Language-Hearing Association [ASHA], 2000b; Justice & Ezell, 2004; National Joint Committee on Learning Disabilities, 2007; Wallach, Charlton, & Christie, 2009). That’s because SLPs are usually the professionals with the deepest understanding of phonological processing and the broadest knowledge about the connections between reading and oral language (Spencer, Schuele, Guillot, & Lee, 2008) and have much to offer others who work with young children when designing pre-literacy programs not only for those at risk, but for all children in the preschool classroom. When working with children in the DL phase, incorporating pre-literacy goals and contexts is an important part of our direct work with clients, and can also serve as a fruitful basis for collaboration with classroom teachers and care-providers. Kaderavek and Justice (2004) outlined the major goals of pre-literacy development during the DL period. These appear in Table 9-3. The goals can be divided into three major categories: phonological awareness, print and alphabet knowledge, and literate language. Table 9-3 Domains for Preliteracy Intervention Adapted from Kaderavek, J., & Justice, L. (2004). Embedded-explicit emergent literacy intervention II: Goal selection and implementation in the early childhood classroom. Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools, 35, 212-228. In addition to PA, however, Kaderavek and Justice (2004) argue that skills related to print and alphabet knowledge are also crucial to emergent literacy development. These skills are sometimes called literacy socialization (Serpell, Sonnenschein, Baker, & Ganapathy, 2002; Snow, 1999), and involve understanding how books work and how print represents speech through written language units like letters, words, and punctuation. Activities that provide instruction and practice in literacy socialization are also important aspects of a pre-literacy program. Finally, the third aspect of pre-literacy instruction has to do with the development of literate language. Literate language is the style used in written communication and is typically more complex and less related to the physical context than the language of ordinary conversation. We’ll say a lot more about literate language in Chapter 10, but for now, we need to be aware that the ability to understand literate language is the “third leg” of a comprehensive pre-literacy program. As we work with children in clinical sessions, with teachers as consultants, or in classrooms as collaborative interventionists, we can introduce literate language forms to preschool children by exposing them to stories, poems, plays, and other texts that exemplify this more elaborate language style, and giving them the opportunity to interact with these texts by hearing them, acting them out, retelling them, and relating them to personal experiences. Kaderavek and Justice (2004) review research that demonstrates that both for children with language impairments, and for those at risk for reading problems due to poverty or language differences, explicit pre-literacy instruction in these areas, which is embedded in preschool classroom routines and activities, has positive effects on children’s readiness for learning to read. Preschool programs that provide direct instruction and practice in name recognition and writing, alphabet recitation and recognition, awareness of book and print conventions, and PA games have been shown to lead to significantly greater growth in emergent literacy skills than programs that merely expose children to books and print (Justice, Chow, Capellini, Flanigan, & Colton, 2003; Justice & Ezell, 2004). In addition to incorporating PA within speech intervention for children with speech delays, SLPs can also consult with teachers on how to address emergent literacy for all children in the preschool classroom. SLPs can identify the relevant areas of pre-literacy to address, using guidelines like those in Table 9-3; assist in designing lessons to provide instruction and practice of these skills in high interest activities tied to classroom themes; work alongside the classroom teacher to present the instruction and provide extra support to children who are having difficulty; and carefully monitor children’s participation and progress in the classroom activities to identify those who might need more intensive intervention in these areas (Gillam & Justice, 2010; Kaderavek & Justice, 2004). In Chapter 3, we discussed three major methods of intervention identified by Fey (1986): clinician-directed (CD), child-centered (CC), and hybrid. As we discussed in Chapter 3, the goal for us as clinicians is not to choose one method and use it consistently, but to have a repertoire of methods available that we can match to the needs of individual clients and the particular goals being addressed. In this way we can maximize the efficiency of our intervention and have the greatest chance that it will generalize to the client’s everyday communication. Let’s look at each of these methods to see how they might be applied to the child with DL. In Chapter 3, we looked at a variety of clinician-directed approaches geared for the DL period. These included drill; drill play; Leonard’s (1975a) CD modeling; and Lee, Koenigsknecht, and Mulhern’s (1975) Interactive Language Development Teaching. There also are a variety of commercially available intervention packages, including some computer software, that use a CD approach to intervention for targets within the DL phase. Remember that CD approaches are highly effective in eliciting forms in production that the child has not used before or has used very infrequently. When initial elicitation of new forms is the goal, CD approaches make good sense for clients who can tolerate them. The weakness of CD approaches is their failure to generalize to real communication and their tendency to place the child in a passive respondent role. There are two ways to address these problems. One is to follow Fey’s (1986) advice and use the techniques outlined in Chapter 3 to increase the naturalness of CD activities. The second is to supplement CD approaches with other methods that give the client an opportunity to practice newly acquired forms in assertive roles and in the service of genuine communication. Let’s look at some examples of CD approaches that might be used for several of the typical goals of intervention at the level of DL. One issue that often arises in phonological training is the question of whether to provide discrimination drills in which the child must identify pictures of words containing contrasting sounds (toe/sew) before production practice begins. This practice has been controversial, but recent research (Rvachew & Grawburg, 2006; Wolfe et al., 2003) suggests that discrimination training is helpful only if the child fails to discriminate sounds on which production errors appear, prior to therapy. For these sounds, active discrimination drills worked better than auditory bombardment in increasing discrimination ability. But for sounds the child could discriminate at the beginning of training, additional discrimination training showed no positive effects. These findings suggest that assessing discrimination of sounds in error should be part of the assessment for speech delays and the use of discrimination drills should be reserved for only those sounds the child has been shown to have difficulty differentiating. Articulation drills are a standard part of traditional intervention for speech disorders. Shriberg and Kwiatkowski (1982a) showed that drill was effective for improving phonological production in children in the DL period (even though neither clinicians nor preschool children liked it very much). Contrastive drills are one particular kind of drill often used in phonological intervention for children with DL. Contrastive drills involve developing lists of pairs of words in which the two words in each pair differ in specific ways. In a minimal pairs approach, two words that differ by only one feature of the target phoneme are presented for contrast (Baker, 2010; Saben & Ingham, 1991; Weiner, 1981). For example, if stopping of fricatives is a pattern being targeted, a list of pairs of words would be developed in which one word contained a fricative and a contrasting word contained the corresponding stop. Examples would be sew/toe, zoo/do, fat/pat, and nice/night. The client is asked to say each pair of words. The hope is that having the contrasting words in the same context will encourage the client to differentiate between them, preferably by suppressing the phonological pattern that would make them homonymous. The maximal opposition (Gierut, 1990) or multiple oppositions (Williams, 2010) approach also opposes pairs of words, but this approach contrasts words that differ maximally on the target phoneme, so that the contrasting words differ not just on one feature of the target phoneme but on several. Using stopping of fricatives as our example target pattern again, a maximal opposition approach would contrast pairs such as sew/no, zoo/moo, fat/cat, and nice/nine. Lists of words for use in contrastive drills for various phonological process targets have been published by Elbert, Rockman, and Saltzman (1980) and Godar, Fields, and Schreiber (2004). Kuster (2010) provides additional internet resources for finding these lists. Additional CD approaches for speech sound treatment can be found in Williams et al. (2010). Drill play is often a preferred form of CD intervention at this level. The production practice segment of the Cycles approach, discussed by Prezas and Hodson (2010), uses a drill play format. These authors offered several possible drill play activities that can be incorporated into the production practice phase of phonological intervention. All the activities involve the use of small cards, each with a picture drawn by the client that represents one of the words containing the target phoneme or sequence that is used in the practice session. Some example activities from Hodson & Paden (1991) include the following: 1. Hide and seek. The clinician hides the cards in obvious places around the room; the client says each word as he or she finds the card. 2. Safari. Each card is clipped to a picture of an animal. The client uses binoculars (which may be made from two toilet-paper tubes taped together) to find each animal and says each word on the card attached to it. 3. Sack ball. Large, open shopping bags, each with one of the client’s cards taped to it, are placed around the room. The client throws a softball into a bag and then names the card on that bag. The game is continued until the client has thrown at least once into each bag. 4. Buried. The client’s cards are buried in sand or foam peanuts. The client names each card as it is unearthed.

Intervention for developing language

Intervention policy issues at the developing language level

Individualized educational plans

Family-centered practice

Intervention for developing language: products, processes, and contexts

Intervention products: goals for children with developing language

Area

Goals

Phonology

Increase consonant repertoire.

Increase production of closed syllables.

Decrease use of phonological processes.

Increase production of multisyllabic words.

Increase accuracy of sound production.

Increase intelligibility.

Semantics

Increase vocabulary size.

Increase use of verbs for specific actions (sweep, slide, bend, fold, etc.).

Increase appropriate pronoun use.

Increase understanding and use of basic concept vocabulary (spatial terms, temporal terms, diectic terms, kinship terms, color terms, etc.).

Increase range of semantic relations expressed within sentences (possession, recurrence, location, etc.).

Increase range of semantic relations expressed between clauses (sequential, causal, conditional, etc.).

Increase use of appropriate conjunctions (but, so, etc.).

Syntax

Increase sentence length.

Increase sentence complexity (use of prepositional phrases, noun modifiers, verb marking, etc.).

Increase use of a variety of sentence types (questions, negatives, conjoined and embedded, passives, etc.).

Increase use of appropriate auxiliary verbs (can, will, must, have, is, are, etc.).

Increase use of copula verbs (is, am, was, were, etc.).

Increase understanding of word order in sentences.

Morphology

Increase use of simple morphemes on nouns (plural, possessives, etc.).

Increase use of verb markers (tense, number, aspect, etc.).

Increase use of higher-level morphemes (-er, -est, etc.).

Increase appropriate use of articles (a, an, the).

Pragmatics

Increase use of verbal forms of communication.

Increase use of language to achieve communicative goals.

Increase flexibility of language forms for various contexts.

Increase ability to initiate communication with appropriate forms.

Expand range of communicative intentions expressed with a variety of language forms.

Increase ability to maintain conversational topics.

Increase ability to manage conversational turn-taking, topic-shifting.

Begin to use various genres of language (e.g., narration).

Increase ability to make and request conversational repair.

Play and thinking

Increase ability to use objects to represent others.

Increase use of pretend and imaginative play.

Increase play that involves social role-playing.

Increase ability to use language to foster abstract thought.

Increase ability to use language to negotiate peer interactions.

Increase ability to use language to self-monitor and inhibit aggressive behavior.

Preliteracy

Listen to stories; talk about pictures and events in books.

Look at books independently; orient book properly, turn pages.

Recognize parts of books: pages, title, orientation of print.

Recognize words in print (e.g., find first word on a page, count words on a page).

Begin to develop metalinguistic and phonological awareness:

Develop awareness of rhyme.

Count syllables in words.

Sing alphabet song; identify letters.

Begin to be able to segment words into syllable and sound units.

Know what a word is.

Identify words that start/end with the same sound.

Count sounds in words.

Match sounds and letters.

Phonology

Semantics

Syntax and morphology

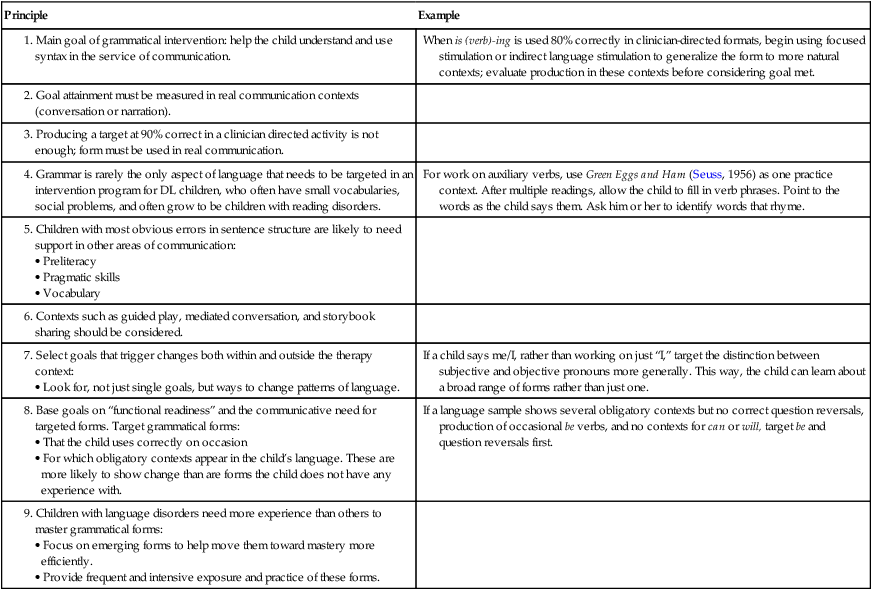

Principle

Example

When is (verb)-ing is used 80% correctly in clinician-directed formats, begin using focused stimulation or indirect language stimulation to generalize the form to more natural contexts; evaluate production in these contexts before considering goal met.

For work on auxiliary verbs, use Green Eggs and Ham (Seuss, 1956) as one practice context. After multiple readings, allow the child to fill in verb phrases. Point to the words as the child says them. Ask him or her to identify words that rhyme.

If a child says me/I, rather than working on just “I,” target the distinction between subjective and objective pronouns more generally. This way, the child can learn about a broad range of forms rather than just one.

If a language sample shows several obligatory contexts but no correct question reversals, production of occasional be verbs, and no contexts for can or will, target be and question reversals first.

Comprehension versus production targets

Pragmatics

Play and thinking

Preliteracy

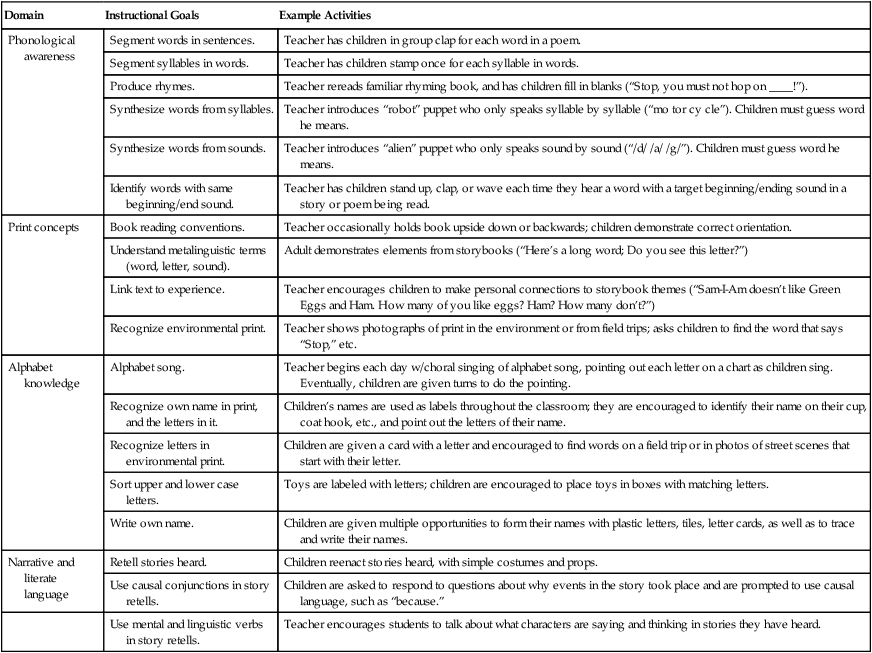

Domain

Instructional Goals

Example Activities

Phonological awareness

Segment words in sentences.

Teacher has children in group clap for each word in a poem.

Segment syllables in words.

Teacher has children stamp once for each syllable in words.

Produce rhymes.

Teacher rereads familiar rhyming book, and has children fill in blanks (“Stop, you must not hop on ____!”).

Synthesize words from syllables.

Teacher introduces “robot” puppet who only speaks syllable by syllable (“mo tor cy cle”). Children must guess word he means.

Synthesize words from sounds.

Teacher introduces “alien” puppet who only speaks sound by sound (“/d/ /a/ /g/”). Children must guess word he means.

Identify words with same beginning/end sound.

Teacher has children stand up, clap, or wave each time they hear a word with a target beginning/ending sound in a story or poem being read.

Print concepts

Book reading conventions.

Teacher occasionally holds book upside down or backwards; children demonstrate correct orientation.

Understand metalinguistic terms (word, letter, sound).

Adult demonstrates elements from storybooks (“Here’s a long word; Do you see this letter?”)

Link text to experience.

Teacher encourages children to make personal connections to storybook themes (“Sam-I-Am doesn’t like Green Eggs and Ham. How many of you like eggs? Ham? How many don’t?”)

Recognize environmental print.

Teacher shows photographs of print in the environment or from field trips; asks children to find the word that says “Stop,” etc.

Alphabet knowledge

Alphabet song.

Teacher begins each day w/choral singing of alphabet song, pointing out each letter on a chart as children sing. Eventually, children are given turns to do the pointing.

Recognize own name in print, and the letters in it.

Children’s names are used as labels throughout the classroom; they are encouraged to identify their name on their cup, coat hook, etc., and point out the letters of their name.

Recognize letters in environmental print.

Children are given a card with a letter and encouraged to find words on a field trip or in photos of street scenes that start with their letter.

Sort upper and lower case letters.

Toys are labeled with letters; children are encouraged to place toys in boxes with matching letters.

Write own name.

Children are given multiple opportunities to form their names with plastic letters, tiles, letter cards, as well as to trace and write their names.

Narrative and literate language

Retell stories heard.

Children reenact stories heard, with simple costumes and props.

Use causal conjunctions in story retells.

Children are asked to respond to questions about why events in the story took place and are prompted to use causal language, such as “because.”

Use mental and linguistic verbs in story retells.

Teacher encourages students to talk about what characters are saying and thinking in stories they have heard.

Intervention procedures for children with developing language

Clinician-directed methods

Phonology

Speech sounds

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Rachel was a friendly, likable little girl who loved to talk even though people sometimes had trouble understanding what she said. She was born with Down syndrome and has been enrolled in early intervention since she was an infant, first in a home program and later in a mainstream preschool, with special services in speech-language and special education provided by the local school district. Now she was close to 7 years old. Her parents were very committed to continuing mainstream education for Rachel, and her preschool teacher, special educator, and speech-language pathologist (SLP) thought Rachel could function in a mainstream kindergarten class, with some support services. Her school district and the kindergarten teacher were somewhat hesitant to go along with this plan. The kindergarten teacher was afraid Rachel would “hold her class back.” The school district felt it would be more manageable logistically to provide services in a self-contained program for children with intellectual disabilities (ID), which was housed on the other side of town from Rachel’s home. The school district developed an Individualized Educational Plan (IEP) for Rachel that included the self-contained class placement. At the IEP meeting, the parents rejected that plan, insisting that Rachel be allowed to try the kindergarten class in the neighborhood school. Reluctantly, the school-district team agreed to the plan and devised a range of special services that Rachel would receive within the classroom setting, including special education, speech-language pathology, and occupational therapy.

Rachel was a friendly, likable little girl who loved to talk even though people sometimes had trouble understanding what she said. She was born with Down syndrome and has been enrolled in early intervention since she was an infant, first in a home program and later in a mainstream preschool, with special services in speech-language and special education provided by the local school district. Now she was close to 7 years old. Her parents were very committed to continuing mainstream education for Rachel, and her preschool teacher, special educator, and speech-language pathologist (SLP) thought Rachel could function in a mainstream kindergarten class, with some support services. Her school district and the kindergarten teacher were somewhat hesitant to go along with this plan. The kindergarten teacher was afraid Rachel would “hold her class back.” The school district felt it would be more manageable logistically to provide services in a self-contained program for children with intellectual disabilities (ID), which was housed on the other side of town from Rachel’s home. The school district developed an Individualized Educational Plan (IEP) for Rachel that included the self-contained class placement. At the IEP meeting, the parents rejected that plan, insisting that Rachel be allowed to try the kindergarten class in the neighborhood school. Reluctantly, the school-district team agreed to the plan and devised a range of special services that Rachel would receive within the classroom setting, including special education, speech-language pathology, and occupational therapy.