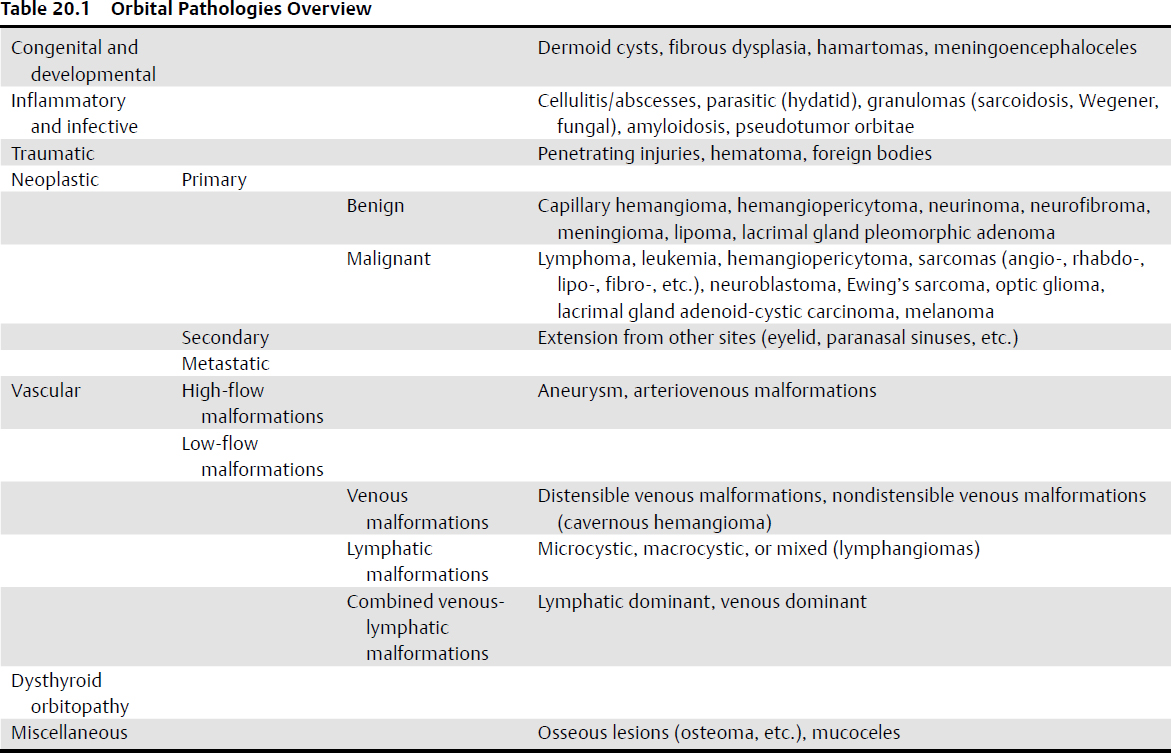

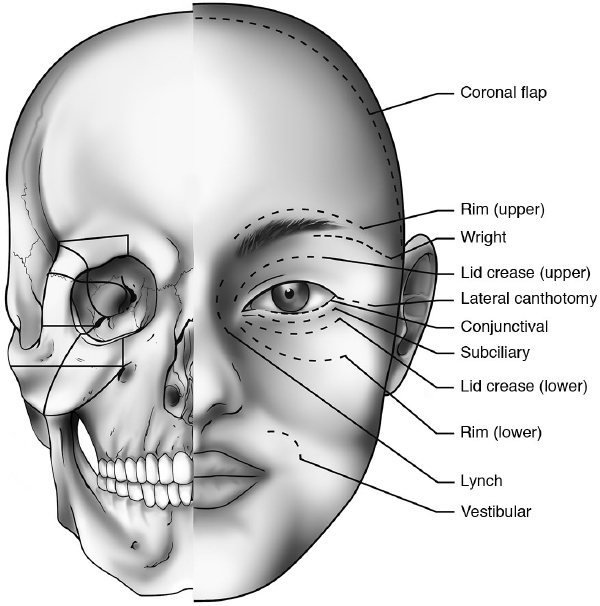

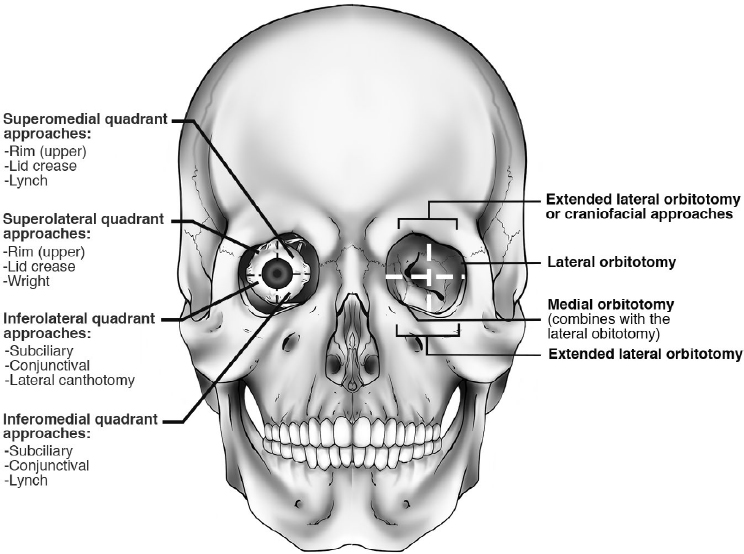

20 Intraorbital Pathologies and Surgical Approaches • Intraorbital diseases have different age-related patterns of progress over different periods of time (Table 20.1). • Thyroid-associated orbitopathy is more frequent in Western countries and is the most common intraorbital disease in the Americas and Europe. • In adults, the most frequently diagnosed malignant lesions involving the orbit are non-Hodgkin’s lymphomas; extensions from basal cell carcinoma (BCC); and metastases, most commonly of BCC.1,2 Choroidal melanoma is the most commonly diagnosed primary ocular malignant lesion, but it occurs less frequently than the other malignancies cited above. Cavernous hemangioma is the most common benign lesion involving the orbit. • Dermoid and epidermoid cysts are the most common benign lesions in children, whereas sarcomas (rhabdomyosarcomas) are the most common orbital malignant tumors (retinoblastoma is the most common intraocular malignancy in the pediatric population). Lymphoproliferative diseases are rare in children, accounting for less than 5 to 10% of orbital lesions. • Orbital cellulitis: incidence: 1.6/100,000/year in children; 0.1/100,000/year in adults.3 Orbital infections are more common in younger patients and more severe in older ones. Infectious orbital pathologies, although rare (about 2% of the pathologies affecting the orbit), are a serious condition with potentially life-threatening consequences.4 • Review anatomy in Chapter 2, page 43. • Basic principles of all surgery: bloodless field, adequate exposure and visualization, proper instrumentation, delicate manipulation. In benign expansive lesional surgery, keep the most intimate plane around the capsule of the lesion. Clinical Evaluation of Patients with Orbital Diseases: Practical Checklist • Vision acuity: It is critical to measure visual acuity before any treatment is performed. Documentation for medicolegal issues is paramount. Reduced vision suggests involvement of the optic nerve or globe. • Pupils: Evaluate the shape and symmetry of pupils. Extraocular movements: It is useful to note even minimal abnormal movements because a slight limitation in one eye may be the only evidence of orbital pathology. • Color vision: Assessment of color vision is very important for evaluating optic nerve function. It can be done simply with Ishihara color plates; there is no need for more sophisticated tests. • Inspection: Evaluate the entire face, focusing on proportion and symmetry. • Globe displacement: Globe displacement does not always result in diplopia, but evaluating the position of the globe can be an important sign for many conditions (e.g., orbital trauma). • Palpation: Palpate the upper and lower eyelid very carefully. Check the orbital rim for any step deformities or fractures. • Eyelid color: Eyelid color can provide some information regarding orbital pathologies. In inflammatory disorders, eyelids are often erythematous. Spontaneous hemorrhage most frequently occurs with hemangioma and lymphangioma, which can also have bluish color. Specialist Evaluation (see also Chapter 10) • Slit-lamp examination: This exam is useful for evaluating the status of the cornea (and for evaluating exposure keratopathy). Several pathological conditions cause dilatation of conjunctival vessels and edema. In very severe cases the suspicion of a carotid-cavernous fistula should be raised. • Intraocular pressure • Fundus examination: This exam is necessary to assess the optic nerve. For example, tumors compressing the optic nerve produce disk edema or optic atrophy. • Pulsations: Pulsations can be present in neurofibromatosis or in any other conditions in which brain pulsation can be transmitted to the orbital content. Extremely vascularized orbital tumors can also generate pulsations. • Exophthalmometry: to evaluate proptosis. • Forced duction test: to evaluate the movement of a given extraocular muscle. • Nasal endoscopy: to evaluate the presence of sinonasal pathologies (inflammatory, neoplastic). • The choice of the approach should be made based on the site, the anatomic relationships, and the suspected nature of the lesion; for example, a regional approach is appropriate for the orbit.4 Each area can be reached by different approaches, with each providing a different angle of attack. • The orbital skeleton and bony rim can limit surgical maneuvers in a narrow anatomic space. Sometimes bony work is necessary to increase operative space. Orbital or cranio-orbital bone segments may temporarily be removed and replaced in their original position without any morphological sequelae. • Surgical access to orbital skeleton and periorbital structures through the eyelids and anterior orbit can be done using a wide range of skin and conjunctival incisions5 (Fig. 20.1). The choice of the incision is greatly influenced by the surgeon’s personal experience and the surgical target lesion. • Orbital marginotomies available for surgical treatment of orbital diseases can be classified into four procedures based on the bony wall to be treated: inferior, lateral, superior, and medial.6 Orbital bony disassembling can be performed as required (Fig. 20.1). • Transcranial approaches can be used for orbital tumors located medially in the orbital apex, optic canal, and select orbital tumors with intracranial extension. Among these approaches, the frontal, frontotemporal, and frontotemporal-orbitozygomatic (FTOZ) approaches, with or without preservation of the supraorbital rim, are very versatile (Table 20.2). Fig. 20.1 Skin and conjunctival incision (right) and orbital marginotomies (left) to access orbital lesions. Table 20.2 Surgical Approaches to the Orbit

Intraorbital Diseases

Intraorbital Diseases

The incidence and prevalence of various orbital pathologies vary geographically.

The incidence and prevalence of various orbital pathologies vary geographically.

Orbital Approaches

Orbital Approaches

Superior orbit | Coronal approach Superior eyelid approach Eyebrow approach Other neurosurgical approach (temporal, frontotemporal, etc.) |

Lateral orbit | Lateral orbitotomy (Kronlein approach and variations) Superior eyelid approach Superior eyebrow approach Swinging eyelid approach |

Inferior orbit | Swinging eyelid approach Transconjunctival approaches Inferior eyelid approach Transantral-transvestibular approach |

Medial orbit | Trans-/precaruncular transconjunctival approach Transfacial approach (Lynch or paralateronasal incision) Transnasal approach |

• Endoscopic-assisted orbital approaches can offer improved visualization in select cases and minimize the amount of bone work required.

Coronal Approach

Coronal Approach

• Very versatile with multiple accessible areas: fronto-orbital region, upper and middle regions of the facial skeleton, anterior and middle cranial fossa

• Enables adequate management of the superolateral aspect of the whole orbit

Dissect the lateral orbital rim in a subperiosteal fashion. Complete the exposure of lateral orbital rim and zygomatic regions.

Dissect the lateral orbital rim in a subperiosteal fashion. Complete the exposure of lateral orbital rim and zygomatic regions.

Surgical Anatomy Pearl

In orbital dissection, be aware of the position of the medial canthal tendon.

Approaches to the Anterior Half of the Orbit (Fig. 20.2)

Approaches to the Anterior Half of the Orbit (Fig. 20.2)

Medial Approaches

These approaches are used to access the roof and floor of the orbit, nasolacrimal region, ethmoidal complex, sphenoid sinus, and medial aspect of optic canal.

Transcutaneous approach—Lynch incision7: Make a slightly curved vertical incision down to the periosteum, beginning along the inferior aspect of the medial brow, midway between the medial canthus and the dorsum of the nose. Manage the local vessels (angular artery and vein). Once the periosteum is reached, dissect it in a subperiosteal plane. The medial canthal ligament may be elevated, but reapproximate it at the end of the procedure.

Transcutaneous approach—Lynch incision7: Make a slightly curved vertical incision down to the periosteum, beginning along the inferior aspect of the medial brow, midway between the medial canthus and the dorsum of the nose. Manage the local vessels (angular artery and vein). Once the periosteum is reached, dissect it in a subperiosteal plane. The medial canthal ligament may be elevated, but reapproximate it at the end of the procedure.

Superior eyelid incision (medial half) and medial lid crease4: Used to access the medial wall and floor of the orbit as well as anterior orbital fat.

Superior eyelid incision (medial half) and medial lid crease4: Used to access the medial wall and floor of the orbit as well as anterior orbital fat.

• Make the skin incision on a crease. Elevate the orbicularis muscle flap and identify the orbital rim. Laterally push the levator muscle. Expose the intraconal orbital fat. Trochlea and superior oblique muscle should be identified, and they can be temporarily detached (with limited functional impairment). Less scarring will occur postoperatively, but this approach provides a narrower window for deep work.5 Incise and elevate the periorbita to gain access to the medial orbital wall.

• Potential risks: damage to lacrimal system and trochlea with subsequent diplopia.

• Limitations: limited access to orbital floor, and residual scarring (may be minimized with technical modifications).

Transconjunctival approaches: include the “pericaruncular” approaches (precaruncular and transcaruncular), as well as the medial inferior fornix approach.

Transconjunctival approaches: include the “pericaruncular” approaches (precaruncular and transcaruncular), as well as the medial inferior fornix approach.

1. Pericaruncular approaches (pre- and transcaruncular). Induce vasoconstriction in the caruncle and semilunar fold region. Protect the cornea. Retract the upper and lower eyelid with sutures or retractors. Minimally retract the globe laterally with a malleable retractor and make a vertical incision. In the transcaruncular route, the incision is made in the region of the caruncle, whereas in precaruncular approaches, the incision is made just anterior to the caruncle.8 Perform subconjunctival dissection. Identify the posterior limb of the medial canthal tendon and dissect it until the posterior lacrimal crest is reached (the posterior lacrimal crest can be identified with the surgical instruments). Identify the periorbita and incise it immediately posterior to the posterior lacrimal crest. Then, push the orbital content laterally in order to expose the medial wall of the orbit, from the floor to the roof, and from the posterior lacrimal crest to the optic canal/nerve. Identify and manage the anterior and posterior ethmoidal arteries. The following intraorbital dissection is based on the pathology to be treated. For example, orbital and optic nerve decompression can be performed by removing the lamina papyracea and medial aspect of the optic canal. If intraconal work is needed, the medial rectus muscle can be detached (it must be reattached at the end). If more space is needed, perform a lateral orbitotomy with lateral displacement of orbital content, in order to move the eyeball more laterally.9 At the end of the procedure, closure of the conjunctiva is essential.

2. Medial inferior fornix approach. This approach provides access to the anterior intraconal space. Perform a medial 180-degree conjunctival incision close to the corneal limbus. Elevate the conjunctival flap and identify the anterior attachment of the medial rectus muscle. This approach eventually requires resection and medial retraction of the medial rectus muscle. Next, enter the tenon capsule. Intraconal fat is gently managed, and the anterior segment of the optic nerve can be exposed. Conjunctiva closure is essential following procedure completion.

Potential risks: bleeding from vortex veins, and damage to the posterior ciliary vessels and central retinal artery.

Complications: Disruption of the Horner muscle might allow the medial aspects of the eyelids to fall anteriorly away from the globe; lacrimal system damage.

Lateral Approaches

These approaches are used to access the lacrimal fossa region, lateral extra- and intraconal spaces, and anterior and middle cranial base.

Superior eyelid incision (see Superior Approaches, below). This versatile route provides adequate exposure of the lateral wall of the orbit until the superior orbital fissure is reached. It is mostly utilized for extraconal work and cranial base approaches instead of for intraconal work. Endoscopic assistance is very helpful in deep work.

Superior eyelid incision (see Superior Approaches, below). This versatile route provides adequate exposure of the lateral wall of the orbit until the superior orbital fissure is reached. It is mostly utilized for extraconal work and cranial base approaches instead of for intraconal work. Endoscopic assistance is very helpful in deep work.

Lateral rim approach/lateral canthal approach. Mostly dedicated to laterally placed, retrocanthal, anterior and mid-orbit lesions. Make a cutaneous incision from the lateral canthus toward the temporal fossa. Then perform a lateral canthotomy and superior and inferior lateral cantholysis. The superior and inferior palpebral limbs are tagged with stitches. Incise the periorbita and lift it from the lateral orbital wall to gain access to the superolateral extraconal space. At the end of the procedure, reapproximate the limbs of the lateral canthal tendons.10,11 The lateral canthal tendon can sometimes be spared and not bisected by working just above and below it.4

Lateral rim approach/lateral canthal approach. Mostly dedicated to laterally placed, retrocanthal, anterior and mid-orbit lesions. Make a cutaneous incision from the lateral canthus toward the temporal fossa. Then perform a lateral canthotomy and superior and inferior lateral cantholysis. The superior and inferior palpebral limbs are tagged with stitches. Incise the periorbita and lift it from the lateral orbital wall to gain access to the superolateral extraconal space. At the end of the procedure, reapproximate the limbs of the lateral canthal tendons.10,11 The lateral canthal tendon can sometimes be spared and not bisected by working just above and below it.4

• Possible complications: eyelid retraction and lateral canthal tendon malfunction

Lateral lid crease/lacrimal keyhole approach. Mostly dedicated to the lacrimal gland region. Make the incision as for the superior eyelid approach. Drill out the superolateral rim from a lateral direction and create a segmental superior rim opening. Spare the Whitnall tubercle region.

Lateral lid crease/lacrimal keyhole approach. Mostly dedicated to the lacrimal gland region. Make the incision as for the superior eyelid approach. Drill out the superolateral rim from a lateral direction and create a segmental superior rim opening. Spare the Whitnall tubercle region.

Another option is drilling down the rim in order to visualize the lateral wall through the eyelid incision.4

Another option is drilling down the rim in order to visualize the lateral wall through the eyelid incision.4

Transconjunctival approach/lateral inferior fornix approach. Mostly utilized for inferolateral orbital wall, anterior and mid-orbit inferolaterally located lesions.

Transconjunctival approach/lateral inferior fornix approach. Mostly utilized for inferolateral orbital wall, anterior and mid-orbit inferolaterally located lesions.

• Make an incision in the lateral inferior fornix and perform an inferior lateral cantholysis as well. Dissect the periorbita from the orbital wall. Skeletonize the orbital wall as needed and manage the intraorbital lesion. At the end, reattach the lateral portion of the inferior tarsal plate to the residual portion of the lateral canthal tendon (the suture should grasp the superior limb of the tendon in order to make the inferior eyelid adapt well to the globe).

• Complications: pre-septal scarring with eyelid retraction, inferior eyelid malposition, bleeding.

Superior Approaches

These approaches are used to access the extra- and intraconal anterosuperior and superonasal spaces, lateral wall, anterior and middle cranial fossa. Various cutaneous incisions are possible: superior eyelid (which is more appealing cosmetically), brow, and sub-brow incisions.

Brow and sub-brow approach. Make the incision to reach the periosteum of the orbital rim. Elevate the periorbit until the target area is reached, and open the periorbita for management of the intraorbital lesion. Drainage and closure in layers is essential following procedure completion.

Brow and sub-brow approach. Make the incision to reach the periosteum of the orbital rim. Elevate the periorbit until the target area is reached, and open the periorbita for management of the intraorbital lesion. Drainage and closure in layers is essential following procedure completion.

Superior eyelid approach. Make the skin incision on a lid crease. Identify the orbicularis muscle. Raise the suborbicularis flap and reach the superolateral orbital rim. The orbital septum can be spared or violated, depending on the target one wishes to reach. If it is violated, orbital fat invades the field and should be managed. If an intraconal target has to be reached, cut the levator aponeurosis and Müller’s muscle. This maneuver can be done transversally or vertically. The latter option causes fewer postoperative problems. In the transverse maneuver, the superior aponeurotic system should be reapproximated at the end of the procedure.

Superior eyelid approach. Make the skin incision on a lid crease. Identify the orbicularis muscle. Raise the suborbicularis flap and reach the superolateral orbital rim. The orbital septum can be spared or violated, depending on the target one wishes to reach. If it is violated, orbital fat invades the field and should be managed. If an intraconal target has to be reached, cut the levator aponeurosis and Müller’s muscle. This maneuver can be done transversally or vertically. The latter option causes fewer postoperative problems. In the transverse maneuver, the superior aponeurotic system should be reapproximated at the end of the procedure.

Surgical Anatomy Pearl

Care should be taken to prevent damage to the superior oblique muscle tendon. The septum should not be closed, to avoid postoperative lagophthalmos.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Paralateronasal incision: an inferior extension of the Lynch incision. It is performed when a wider window is needed and the lesion is not confined to orbital spaces.

Paralateronasal incision: an inferior extension of the Lynch incision. It is performed when a wider window is needed and the lesion is not confined to orbital spaces.