Chapter 7 Intramedullary Tumors

ASTROCYTOMA

EPIDEMIOLOGY

• In the pediatric population this tumor is the most common glial neoplasm and is typically low grade.2

DISTRIBUTION

• Astrocytomas may involve any region of the spinal cord, although the cervical area is most commonly affected in children.2

HISTOLOGY/GRADING

General

• These tumors are composed of neoplastic astrocytes that demonstrate immunoreactivity for glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP).

Pilocytic Astrocytoma (Grade I)

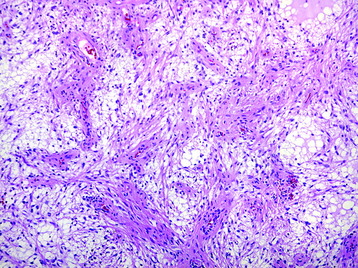

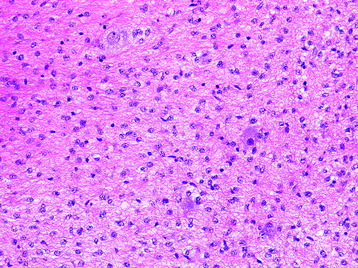

• The classic histologic phenotype is of a biphasic neoplasm composed of looser (and cystic) areas with protoplasmic astrocytes and densely cellular areas composed of hair-like (piloid) cells (Fig. 7-1).

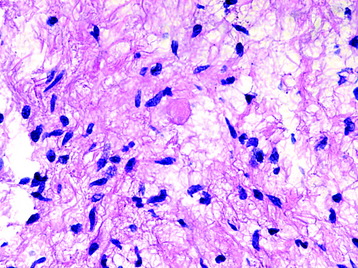

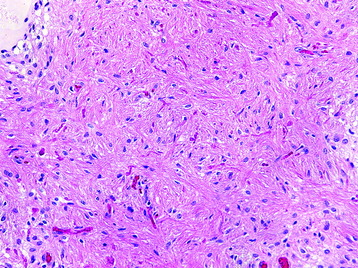

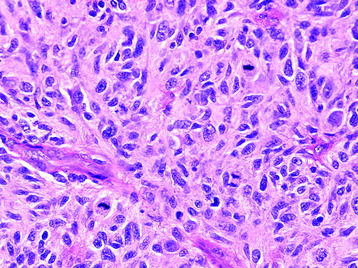

• Eosinophilic granular bodies (Fig. 7-2) are more commonly found in loose areas, whereas Rosenthal fibers (Fig. 7-3) predominate in densely cellular areas.

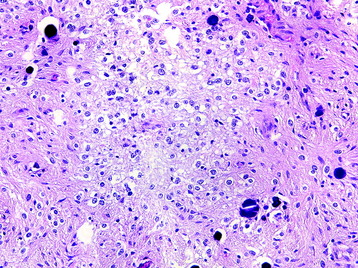

• Oligodendroglial-like cells (cells with rounded nuclei and perinuclear clearing) may be prominent in some regions (Fig. 7-4).

• The histologic differential includes gliosis (particularly when only densely cellular areas are sampled) and rarely occurring oligodendrogliomas or other tumors with clear cell histology (e.g., ependymoma).

Diffuse Astrocytoma (Grade II)

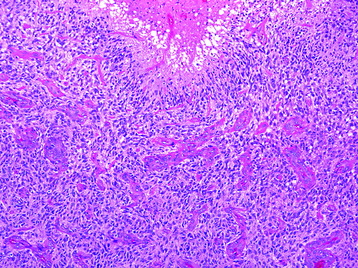

• This neoplasm shows relatively low cellularity and is composed of cells with angulated nuclei and modest nuclear pleomorphism (Fig. 7-5).

• The neoplastic astrocytes may have varied appearances, including fibrillary or gemistocytic (plump).

• Low mitotic activity without evidence of microvascular proliferation or pseudopalisading necrosis is characteristic.

• The histologic differential includes ganglioglioma if infiltrated gray matter is sampled. The presence of a population of clearly dysplastic ganglion cells should be sought to make the diagnosis of ganglioglioma.

Anaplastic Astrocytoma (Grade III)

• The histologic features are similar to the grade II tumors just described, but with the presence of increasing cellularity and mitotic activity.

Glioblastoma (Grade IV)

• Features of anaplastic astrocytoma (Fig. 7-6) with microvascular proliferation and/or pseudopalisading necrosis (Fig. 7-7).

• Occasionally true sarcomatous differentiation may be found (gliosarcoma), but these tumors typically involve the cerebral hemispheres.

• Small cell glioblastoma may be confused with an anaplastic oligodendroglioma. Cytogenetic analyses may help distinguish these tumors. Many oligodendrogliomas demonstrate deletions of the short and long arms of chromosome 1 (1p) and chromosome 19 (19q), respectively, and amplification of the epidermal growth factor receptor gene is found in some small cell glioblastomas.

RADIOLOGY

• Astrocytoma shows slightly low signal or iso-intensity relative to the cord on T1-weighted images (T1WI) and high signal on T2-weighted images T2WI) (Fig. 7-8).

• After injection of intravenous gadolinium, no enhancement of the intramedullary mass is noted. Syringomyelia and hemorrhage are not found.

EPENDYMOMA

EPIDEMIOLOGY

• Spinal intramedullary ependymoma arises from the central canal and accounts for 1.5–3% of central nervous system (CNS) tumors.

DISTRIBUTION

• Ependymomas may be found at any region of the spinal cord, although cervical and cervicothoracic segments are slightly more favored.

HISTOLOGY/GRADING

Most spinal ependymomas are histologically benign and rarely show infiltrative growth. Though they do not form tumor capsules, the interface between the tumor mass and the surrounding normal cord tissue is relatively well defined.4

General

Ependymomas demonstrate cytoplasmic GFAP immunoreactivity. Both punctate intracytoplasmic and ring-like epithelial membrane antigen (EMA) immunoreactivity have been reported in ependymomas.5,6

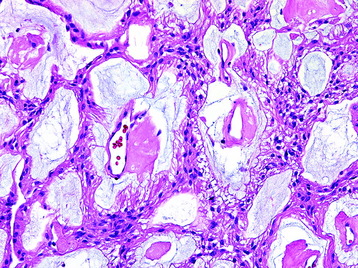

Myxopapillary Ependymoma (Grade I) (Fig. 7-9)

• These tumors demonstrate a papillary architecture composed of vessels covered by a layer of monomorphic cells and separated by pools of mucin.

Ependymoma (WHO Grade II)

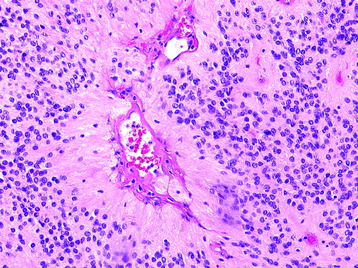

• The cells often aggregate with processes extending to centrally positioned vessels forming perivascular pseudorosettes (Fig. 7-10).

• Microvascular proliferation and sheet-like growth patterns are not found to an appreciable degree.

• Depending on the degree of sampling, the histologic differential can include other clear cell neoplasms (e.g., oligodendroglioma) and other papillary neoplasms (e.g., choroid plexus lesions), all of which should be distinguishable based on their immunohistochemical profiles.

RADIOLOGY

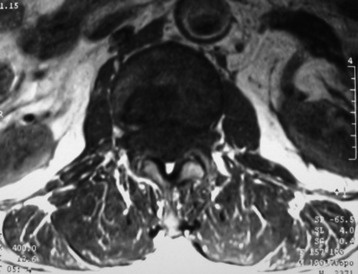

• Spinal intramedullary ependymoma usually shows low-signal intensity on T1WI and high-signal intensity on T2WI MRI (Figs. 7-11 and 7-12).

• It has good contrast enhancement and a well-demarcated margin, but the signal intensity and the degree of enhancement are variable because of the different distributions of the vascular component of the connective tissue in the tumor mass (Figs. 7-13 to 7-15).7

• Homogeneous enhancement is observed in 47% of tumors and heterogeneous enhancement in 53%. In most cases, the interface between the tumor and the spinal cord is clearly identified.

• Associated syrinx is commonly seen in intramedullary ependymomas. It is known that tumor syrinx occurs in more than 50% of cases of intramedullary ependymomas, which is greater than the incidence of syrinx in spinal astrocytomas.

• Syrinx is more commonly found on the cephalic side of the tumor mass than on the caudal side and at the cervical level rather than the thoracolumbar level. These tendencies suggest that the development of the syrinx may be related to the cerebrospinal fluid circulation.9

• The presence of syrinx in intramedullary spinal cord tumors is known to be a good prognostic factor because it enables complete resection of the tumor mass with the provision of an excellent dissection margin between the tumor mass and normal cord tissue.

Fig. 7-12 T1 sagittal MR of myxopapillary ependymoma. The mass signal is isointense to the spinal cord.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree