Issues in Health Outcomes Assessment

Zarya A. Rubin

Samuel Wiebe

Introduction

Epilepsy is a multidimensional disorder with potential consequences for nearly every aspect of a patient’s life, from physical effects, to social and vocational challenges, to personality and mood changes. In addition, total estimated health care costs are $12.5 billion in the United States annually.12,46 Results of recent large clinical studies indicate that 25% to 40% of patients diagnosed with partial epilepsy will not be controlled with medication,37,60,72,73,74,88 and a larger proportion experience adverse antiepileptic medication effects. Epilepsy patients are also more likely to suffer from comorbid depressive disorders than the general population or patients with other chronic illness, with prevalence rates of depression estimated to be 20% to 40%.11,33,50,61,78,84 The comprehensive picture of the experience of epilepsy is more complex and detailed than is often assumed, reaching beyond the seizures themselves and extending into multiple domains of patients’ overall health.

The Concept of Health-related Quality of Life in Epilepsy

Measures of success in treating medical illness have traditionally been characterized as freedom from disease or other intermediate quantifiable endpoints such as reduction in systolic blood pressure, serum glucose, or seizures.21 Over the last decade, however, the emergence of health-related quality of life as a reliable, valid, and significant indicator of overall outcome in patients with epilepsy has begun to alter that perception.28,41,49,95,101

The concept of quality of life is not new, and dates back at least to the time of Aristotle, who attempted to define the attributes of happiness.4 The Constitution of the World Health Organization defines health as “A state of complete physical, mental and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity.”102 The current definition of quality of life encompasses both the concept of health and functional ability, as well as the patient’s perceived satisfaction with this level of functioning. Thus, both objective and subjective measures are incorporated into the final assessment of overall quality of life.

As defined by Gotay et al.,45

Quality of life is a state of well-being that is a composite of two components: (1) the ability to perform everyday activities that reflect physical, psychological and social well-being and (2) patient satisfaction with levels of functioning and the control of disease and/or treatment-related symptoms.

The initial formulation of an instrument designed to measure quality of life in health care occurred in 1948 with the development of the Karnofsky Performance Status Scale. The 100-point scale defined a patient’s ability to perform various activities of daily living (where 100 is capable of performing all normal activities and 0 is deceased).19,58 In 1992, Vickrey et al.95 developed one of the first reliable and valid measure of quality of life in epilepsy, the Epilepsy Surgery Index-55. Baker et al.9 concurrently constructed a model of assessment of physical, social, and psychological impairment related to refractory epilepsy. In 1995, Devinsky et al.29 developed the Quality of Life in Epilepsy Inventory (QOLIE-89), an 89-item, disease-specific inventory to help characterize the impact of epilepsy on patients’ global functioning. Since then, a QOLIE-1025 has been developed in addition to other more specific inventories relating to aspects that contribute to overall quality of life in epilepsy such as medication side effects (Adverse Events Profile)6 and the NDDI-E (Neurologic Disorders Depression Inventory for Epilepsy),38 a newly developed tool for differentiating depression in epilepsy from antiepileptic drug (AED) and cognitive effects.

In a study of 81 consecutive epilepsy patients, Gilliam et al.40 systematically assessed the specific concerns of patients with recurrent seizures. The most frequently cited concern was driving, at nearly 70%, whereas

other significant factors listed by more than one third of patients included independence, work and education, social embarrassment, medication dependence, mood/stress, and safety (Table 1).

other significant factors listed by more than one third of patients included independence, work and education, social embarrassment, medication dependence, mood/stress, and safety (Table 1).

Although these patient-oriented outcome measures are not intended to replace traditional indicators of health status in epilepsy such as seizure frequency or severity, they may offer additional information that allows us to expand our knowledge of the experience of epilepsy and better treat our patients. This review examines the contributions of seizure status, outcomes of epilepsy surgery, mood effects, medication toxicity, and other comorbidities to overall health-related quality of life (HRQOL) in epilepsy.

Seizure Frequency and Health-related Quality of Life

Although seizure frequency was previously believed to predict overall quality of life and seizure reduction continues to be a goal of therapeutic interventions for epilepsy, there in fact exists no clear gradient establishing a direct correlation between number of seizures and degree of HRQOL improvement or worsening. In fact, the only true amelioration in quality of life can be observed when patients are rendered entirely seizure free.14,63,69,96

Table 1 Quality of Life in Epilepsy-89 (QOLIE-89) total and subscale score differences between groups according to depression diagnosis | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

In the multicenter study by Leidy et al.,63 patients were classified according to seizure frequency and evaluated on the Medical Outcomes Short Study Form (SF-36), a “gold standard” measure of quality of life. Scores for seizure-free patients were similar to those of the general population, whereas increasing frequency of seizures predicted a small but inverse shift in HRQOL across all domains.63 Although some differences were observed between groups with differing seizure frequency, these differences were subtle, and the greatest discrepancy in quality-of-life scores was observed in the seizure-free group versus all seizure groups.63 In a recent study by Birbeck et al.,14 these results were confirmed using the QOLIE-31, QOLIE-89, and SF-36, with positive changes in HRQOL occurring only in the group that achieved seizure freedom and not in the groups that achieved seizure reduction. Thus, although many AED trials use a 50% reduction in seizure frequency as a desirable endpoint, it appears that the complete eradication of seizures provides the only definitive HRQOL benefits for patients with epilepsy.14,63

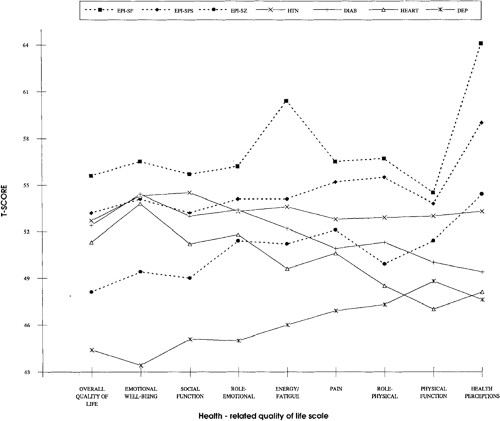

Vickrey et al.95 compared the health status of patients who had undergone epilepsy surgery with those who suffered from other chronic illnesses such as hypertension, diabetes, and heart disease (Fig. 1). Although patients who were rendered completely seizure free scored higher on all measures than patients with chronic illness, patients who continued to have seizures, even without alteration in consciousness, scored similarly to patients with other chronic medical conditions in terms of social and emotional well-being; patients with residual complex partial or generalized tonic–clonic seizures scored significantly worse than patients with myocardial infarction or congestive heart failure on overall QOL and social and emotional well-being.95

These results further emphasize the importance of eliminating seizures to achieve adequate quality of life; even occasional auras impair quality of life to a degree similar to a chronic medical condition such as diabetes.33 By achieving total cessation of seizures, through medical or surgical interventions, patients with epilepsy may attain of a level of quality of life that approaches or surpasses that of the general population.14,63

Surgery and Health-related Quality of Life

In the first randomized, controlled trial comparing epilepsy surgery to conventional therapy, Wiebe et al.100 demonstrated that surgery was far superior to medical treatment in terms of rendering patients free of disabling seizures (58% vs. 8%), with correlative improvements in quality of life. In a recent multicenter observational study with long-term follow-up by Spencer et al.,90 66% of patients experienced a 2-year remission. Success rates for temporal lobe epilepsy with corresponding mesial temporal sclerosis and supportive electroencephalographic (EEG) findings may be considerably higher.39,83

Despite compelling evidence in favor of epilepsy surgery, few patients who are possible candidates are being offered this potentially curative treatment, and those who are being considered for surgery may wait an average of 20 years from diagnosis.42,61 The risks of delaying epilepsy surgery are not insignificant, given that the rate of epilepsy-related death may exceed 1%,91 whereas the reported rate of mortality for epilepsy surgery is <0.2%.13

In addition to freedom from seizures, which is associated with significantly improved health outcomes, Gilliam et al.42 looked at patient-oriented measures after temporal lobectomy for refractory epilepsy, using validated instruments for assessing HRQOL such as the Epilepsy Foundation of America’s (EFA) Concerns Index, the Epilepsy Survey Inventory-55, the Adverse Events Profile, and the Profile of Mood States (POMS).42 In a comparison of a presurgical group of 71 patients to 125 patients who had previously undergone anterior temporal lobectomy, 65% of postoperative patients were found to be seizure free (vs. 0%) and 60% (vs. 27%) were driving.42 Multivariate regression analysis in the postoperative group

demonstrated that factors associated with improved quality of life included mood status, employment, driving, and AED cessation but did not include seizure freedom or IQ status.42

demonstrated that factors associated with improved quality of life included mood status, employment, driving, and AED cessation but did not include seizure freedom or IQ status.42

Markand et al.69 found improvement in overall score and 10 of 17 scales of the QOLIE-89 in patients who had undergone temporal lobectomy versus those treated with conventional medical therapy. However, these improvements were dependent on achieving total seizure freedom.

These studies suggest a complex interaction among variables contributing to HRQOL in patients with epilepsy. By assuming that freedom from seizures, although a primary goal, is the only valuable postsurgical endpoint, we may be missing additional opportunities for intervention in the domains of transportation options, vocational counseling, and treatment of mood symptomatology with medication or psychotherapy. Through examination of the influence of patient-oriented outcomes on postoperative measures of success, we may better be able to characterize the impact of these factors on overall HRQOL in epilepsy and tailor therapeutic approaches accordingly.

Medications and Health-related Quality of Life

Several recent studies have emphasized the importance of medication effects on overall HRQOL in epilepsy. Baker et al.7 surveyed >5,000 European patients with epilepsy and found that 44% of respondents had changed their medications at least once in the last year due to unsatisfactory control. Only 12% of patients reported no side effects from medication; common side effects included tiredness (58%), memory problems (50%), difficulty concentrating (48%), sleepiness (45%), difficulty thinking clearly (40%), and nervousness or agitation (36%). Thirty-one percent of patients had changed their medication at least once in the last year due to side effects.7 This study included patients’ self-report of adverse effects from medication. Baker and colleagues also developed an instrument to systematically evaluate medication-related toxicity: The Adverse Events

Profile (AEP).6 This 19-item instrument was tested and evaluated for internal consistency and was then administered to 200 consecutive epilepsy patients, 62 of whom met enrollment criteria. Patients were then randomized to receive usual care from a neurologist (no AEP) or to have the AEP provided to their neurologist at each visit. Baseline scores on the AEP correlated with scores on the QOLIE-89, and significant improvements in both the AEP and QOLIE-89 were observed in the group for which the neurologist had access to the AEP.6,40 Availability of the AEP also resulted in a significant reduction in seizures as well as more adjustments in medication by their physician compared to patients for whom this additional information was not available.6 These results emphasize the importance of measuring and evaluating medication toxicity as part of the overall care of the epilepsy patient, not only to control for side effects, but also to potentially reduce seizure frequency and improve overall quality of life.

Profile (AEP).6 This 19-item instrument was tested and evaluated for internal consistency and was then administered to 200 consecutive epilepsy patients, 62 of whom met enrollment criteria. Patients were then randomized to receive usual care from a neurologist (no AEP) or to have the AEP provided to their neurologist at each visit. Baseline scores on the AEP correlated with scores on the QOLIE-89, and significant improvements in both the AEP and QOLIE-89 were observed in the group for which the neurologist had access to the AEP.6,40 Availability of the AEP also resulted in a significant reduction in seizures as well as more adjustments in medication by their physician compared to patients for whom this additional information was not available.6 These results emphasize the importance of measuring and evaluating medication toxicity as part of the overall care of the epilepsy patient, not only to control for side effects, but also to potentially reduce seizure frequency and improve overall quality of life.

Gilliam et al. specifically evaluated medication side effects and their association with HRQOL in a prospective study of 195 consecutive patients.37 Patients were screened with the AEP, the QOLIE-89, and the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI). After controlling for age, gender, generalized tonic–clonic seizure frequency and depressive symptoms, adverse medication effects were the strongest predictor of HRQOL. Severity of depression was also found to be independently correlated with overall HRQOL; seizure frequency, however, was not.37

There has been equivocal evidence in the literature as to the relative superiority of monotherapy over “rational polypharmacy” in the treatment of medically refractory epilepsy.82 Although monotherapy may be felt to be insufficient, polytherapy may not necessarily reduce seizure frequency but may incur a host of other, undesirable effects.

A recent study by Pirio Richardson et al.82 looked at QOL and monotherapy in a group of patients with medically refractory epilepsy who had been converted to monotherapy and maintained on treatment for at least 12 months. Forty percent of patients became seizure free and experienced statistically significant improvements in quality of life in several domains, including memory loss, concern over medication long-term effects, difficulty in taking medications, trouble with leisure time activities, and overall state of health.82 Despite methodologic issues in this small study, it suggests that further consideration be given to the notion of monotherapy in medically refractory epilepsy.

In a large study of 547 patients with partial-onset epilepsy and inadequate seizure control or intolerable side effects, conversion to monotherapy was achieved with lamotrigine. Patients were evaluated with the QOLIE-31 and showed significant improvement in multiple domains after conversion to monotherapy. This improvement was independent of seizure control.24

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree