science revisited

neuromuscular transmission

The steps involved in neuromuscular transmission are:

- Motor nerve depolarization produces action potentials

- Sodium enters the nerve through voltage-gated sodium channels

- Repolarization of motor nerves, stopping action potential propagation

- Potassium leaves the nerve through voltage-gated potassium channels

- Opening of presynaptic nerve terminal VGCCs in response to nerve terminal depolarization, allowing calcium to enter the nerve terminal

- Migration and exocytosis of ACh-containing vesicles

- Binding of released ACh to ACh receptors (AChR) on the muscle surface

- ACh binds transiently to the AChR before being released and metabolized by acetylcholinesterase (AChE), or diffusing away

- Opening of AChRs, cation influx (mainly sodium) and muscle membrane depolarization

- Nerve depolarization produces the release of about 100 vesicles which is measured on the muscle surface as an end-plate potential (EPP)

- If the EPP is of sufficient amplitude an all-or-none muscle fiber action potential is generated

- Excitation–contraction coupling and muscle contraction

other important phenomena

- The generation of a muscle fiber action potential depends on the product of pre- and postsynaptic events:

[ACh released] × [Available muscle surface AChRs].

- An excess of released ACh and available AChRs constitutes the “safety factor” of neuromuscular transmission.

- A reduction in either of these may result in neuromuscular transmission failure at a muscle fiber.

- If NMT fails at sufficient numbers of muscle fibers, the compound muscle action potential (CMAP) amplitude will be reduced and the muscle will be weak.

- High-frequency nerve depolarization (during a maximal voluntary contraction or with high-frequency [20–50 Hz] repetitive nerve stimulation [RNS]) increases nerve terminal calcium. This increases ACh release if this is a limiting factor.

- With low-frequency nerve depolarization (e.g. 3 Hz RNS), ACh release is gradually reduced, reaching its nadir at the fourth or fifth stimulation. Other ACh stores are then mobilized and ACh release increases again. If the reduction in released ACh causes the product of [released ACh available × AChRs] to fall below the safety factor – neuromuscular transmission fails at that muscle fiber.

Clinical Features

Although overlapping somewhat with myasthenia gravis (MG), LEMS has distinctive symptoms and signs (Table 18.1) with gradual onset over months or even years. P-LEMS may have a more rapid progression and be associated with recent weight loss. However, P-LEMS and NP-LEMS are otherwise indistinguishable clinically. The cardinal features of LEMS are weakness, usually predominantly affecting the proximal legs and producing gait problems, areflexia or hyporeflexia, and autonomic dysfunction. Subjective gait problems and leg weakness are often more than the objective weakness of individual muscle groups would suggest, underlying the “3 As” of LEMS: gait apraxia, areflexia, and autonomic involvement.

Table 18.1. Myasthenia gravis (MG) versus Lambert–Eaton myasthenic syndrome (LEMS)

| LEMS | MG | |

| Pathophysiology and target antigen | Presynaptic disorder of NMT with antibodies against VGCC | Postsynaptic disorder of NMT with antibodies against AChR or MuSK |

| Clinical | “Legs first” with leg weakness earlier and more severe and EOM or bulbar involvement later and milder | “Head first” with early and more striking EOM and bulbar involvement and legs involved later, if at all |

| DTRs reduced or absent | DTRs normal | |

| Autonomic (PNS > SNS) involvement | No autonomic involvement | |

| Associations | 50% P-LEMS with SCLC in >90% of these 50% NP-LEMS with increased rate of other autoimmune diseases and HLA-B8, -DR3, and -DQ2 | Thymoma in 15% generalized AChR antibody positive MG Hyperplastic thymus in early onset MG with increased rate of other autoimmune diseases and HLA-B8, -DR3, and- DQ2 |

| Electrophysiology | Reduced CMAP amplitudes | Normal CMAP amplitudes |

| Decrement with low frequency (2–5 Hz) RNS | Decrement with low frequency (2–5 Hz) RNS | |

| Increment (>60–100%) with high frequency (20–50 Hz) RNS or after MVC | Significant increment rare | |

| +++ jitter and blocking on SFEMG | ++ jitter and blocking on SFEMG | |

| Serology | Anti-VGCC antibodies in > 90% | Anti-AChR antibodies in 85% generalized MG and 50% ocular MG Anti-MuSK abs in 5% generalized MG |

| Treatment | 3,4-DAP most useful symptomatic | Pyridostigmine most useful symptomatic |

| Immunomodulation with IVIG ≥ Plex (?) | Immunomodulation with Plex = IVIG | |

| Immunosuppression | Immunosuppression | |

| ±removal of SCLC | ±removal of hyperplastic thymus |

3,4-DAP, 3,4-diaminopyridine; AChR, acetylcholine receptor; CMAP, compound muscle action potential; DTR, deep tendon reflexes; EOM, extraocular muscles; IVIG, intravenous immunoglobulin; LEMS, Lambert–Eaton myasthenic syndrome; MG, myasthenia gravis; MuSK, muscle-specific kinase; MVC, maximal voluntary contraction; NMT, neuromuscular transmission; Plex, plasma exchange; RNS, repetitive nerve stimulation; SCLC, small cell lung cancer; SFEMG, single-fiber EMG; VGCC, voltage-gated calcium channel.

Weakness

Present in at least two-thirds of patients initially, almost all LEMS patients eventually develop proximal leg, and to a lesser degree arm, weakness. A history of fluctuation and fatigue suggests a disorder of NMT. Extraocular or bulbar weakness, especially if early or prominent, is unusual in LEMS. Ptosis is more common than diplopia. Severe ptosis or external ophthalmoplegia suggests MG. Said to be characteristic in LEMS is an initial improvement in strength during muscle contraction, before strength fatigues again. This author is not impressed with the sensitivity or specificity of this finding in a blinded assessment.

Hypo- or Areflexia

Deep tendon reflexes (DTRs) are reduced or absent in over 90% of LEMS patients. DTRs of 2+ or more virtually exclude the diagnosis of LEMS. The DTRs may also increase or return after an MVC.

Autonomic

Up to 75% of LEMS patients eventually develop autonomic manifestations. Cholinergic dysfunction produces parasympathetic, or less frequently sympathetic, involvement. A dry mouth is the most common symptom, along with postural hypotension, constipation, or erectile dysfunction. Sluggish pupillary reflexes and abnormal sweating also occur.

Other

Less common manifestations include respiratory involvement, rarely the presenting feature. Given its association with smoking and SCLC, dyspnea from LEMS must be differentiated from underlying pulmonary disease. Myalgia, especially of the proximal legs, occurs in a fifth patients initially and a third eventually. Prominent sensory symptoms with an underlying SCLC suggest a coexistent paraneoplastic sensory neuronopathy. Similarly, ataxia occurs in up to 10% of LEMS cases, and may represent a cerebellar paraneoplastic disorder with antibodies against Hu or even VGCC.

Epidemiology

LEMS is uncommon, with an incidence of approximately 0.4 in 106, 15 times less than MG. The prevalence, even more reduced because of the poor survival of P-LEMS, is about 30–45 times less than MG at 2.5 in 106. However, when specifically looked for, approximately 3% (range 0–6%) of SCLC cases have LEMS, suggesting that it is underdiagnosed. In the author’s experience P-LEMS is more common in newly diagnosed patients than NP-LEMS. Although LEMS occurs from childhood through to being elderly, its association with SCLC means that most individuals are diagnosed in the fifth decade or later. Both genders are equally represented.

Paraneoplastic LEMS

Of LEMS patients 50–60% have an underlying malignancy – SCLC in >90%. SCLC is rare when LEMS starts before the age of 40. Malignancies other than SCLC may simply be incidental findings in P-LEMS, with an as yet undetected SCLC, or in NP-LEMS. In most patients, a SCLC is discovered within 2 years of diagnosing LEMS, rarely as long as 5 years. SCLC may be less extensive in the presence of LEMS, so that investigations looking for a SCLC may initially be negative.

Non-Paraneoplastic LEMS

In 40–50% of LEMS patients no malignancy is found. Other autoimmune diseases and organ-specific autoantibodies are found in up to 30% of patients with NP-LEMS, more than in P-LEMS. NP-LEMS, is associated with the “autoimmune” human leukocyte antigen (HLA) haplotype -B8, -DR3, -DQ2. Thus, NP-LEMS is likely a primary autoimmune disorder such as myasthenia gravis, pernicious anemia, or Graves’ disease.

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of LEMS is often delayed because it is uncommon and may be confused with the more common MG. Presumably because of its association with SCLC, P-LEMS tends to be diagnosed more rapidly than NP-LEMS.

Clinical

The biggest obstacle to diagnosing LEMS is to consider it in the differential of patients presenting with leg weakness. In a patient with what looks like MG, but where extraocular and bulbar manifestations are minimal and DTRs reduced, especially if there is autonomic involvement, LEMS should be considered and the appropriate electrodiagnostic studies and VGCC antibodies performed.

Electrophysiological

The electrophysiological triad in LEMS consists of:

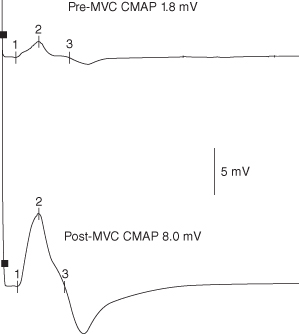

- reduced CMAP amplitudes

- decrement >10% with low-frequency repetitive nerve stimulation (LFS)

- increment with high-frequency stimulation (HFS) or after an MVC.

Motor conduction velocities and sensory studies are normal, unless there is an associated neuropathy.

CMAP amplitudes are reduced, often less than 10% of the lower limit of normal, in over 90% of LEMS patients, especially in studies of distal hand muscles such as abductor digiti minimi (ADM), the most sensitive muscle for studies in LEMS (a paradox given the prominent proximal leg weakness clinically). If normal and LEMS is still suspected, studies to abductor pollicis brevis (ABP), anconeus, or extensor digitorum brevis (EDB) can be performed. Normal amplitudes in all of these muscles virtually exclude LEMS.

Decrement with LFS is found in over 95% of LEMS patients, although this can be difficult to detect if initial CMAP amplitudes are significantly reduced.

Once LEMS is suspected, this should lead to studies looking for increment (also described as facilitation or potentiation) – an increase in CMAP amplitude within seconds of a brief (10–15 s) MVC or during high-frequency (20–50 Hz) RNS. The former is as sensitive as and much less painful than HFS. HFS is still useful in patients too weak to maximally contract or when cooperation is suboptimal, such as in the intensive care unit (ICU). Studies of distal muscles are also more sensitive to detect increment in LEMS. The degree of increment needed to diagnose LEMS is controversial. Although most LEMS patients have increment of more than 2 standard deviations (SDs) above control values, this cut-off would also include a number of MG patients, where increment is occasionally seen. Various authors have used increments of 60%, 100%, or even more as a cut-off for LEMS. Depending on the cut-off, increment is eventually found in over 95% of LEMS patients in at least one of the above target muscles. An increment of more than 100% is seldom found in MG, although rare patients with MG have increments of 300% or more (Figure 18.1).

Figure 18.1. Post-maximal voluntary contraction (MVC) studies of the ulnar nerve to abductor digiti minimi in a patient with Lambert–Eaton myasthenic syndrome. A supramaximal compound muscle action potential (CMAP) was obtained at rest (top) and after 10 s of MVC (bottom). A 340% increment in the CMAP amplitude is demonstrated.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree