Chapter 53 Laminotomy, Laminectomy, Laminoplasty, and Foraminotomy

Positioning

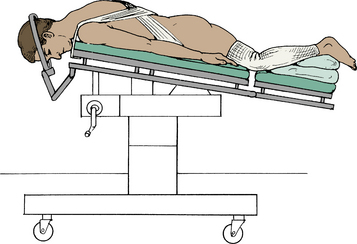

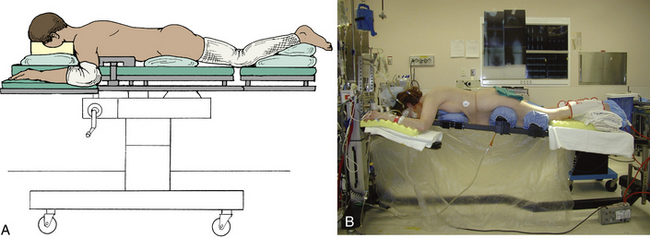

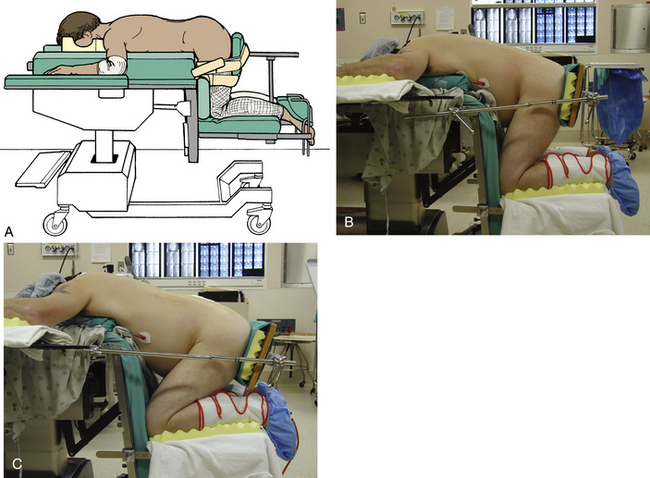

Positioning for thoracic and lumbar decompressive surgery is dictated by the level of the spine being operated upon. Exposure of the upper thoracic spine requires that the patient be prone with the neck moderately flexed, the arms at the side, and the shoulders depressed (Fig. 53-1). Middle and lower thoracic spine exposure requires that the patient be prone, with the arms either at the side or abducted at the shoulders and flexed at the elbows (Fig. 53-2). We recommend that head tongs, such as Gardner-Wells tongs, be used to allow the head to hang freely, thereby avoiding external pressure on the eyes and reducing intraocular pressure. In addition, we prefer that the head of the bed be elevated to reduce facial swelling, which can contribute to airway edema (see Fig. 53-2B). Lumbar exposure may be facilitated in either the prone position, kneeling position (Fig. 53-3), knee-chest position, or lateral decubitus position. The important common feature of all of these positions is the absence of abdominal compression, reducing intra-abdominal pressure and epidural bleeding. It is important to limit hip and knee flexion to approximately 90 degrees or slightly greater to avoid hyperflexion of the knees, which can result in calf swelling and possible compartment syndrome (see Fig. 53-3C). The prone and kneeling position, as compared with the lateral decubitus position, allows complete exposure of the dorsal elements from the cranium to the sacrum. It allows the surgical assistant to have an adequate view of the vertebral column and allows at least four hands to be available to help with the procedure. Surgeries are currently rarely done in the lateral decubitus position. There are, however, potential disadvantages of the prone position. These include restriction of thoracic expansion, compression of the abdominal viscera (producing increased venous pressure in the epidural venous plexus), and the potential for ocular and peripheral nerve compression. These disadvantages can be obviated by use of a Jackson operating table with Gardner-Wells skull traction, as was noted earlier in the chapter (see Fig. 53-2B). This setup allows the abdomen to hang freely, thereby eliminating abdominal compression, and suspends the head, thereby eliminating the potential for ocular pressure and facial abrasions.

To position for upper thoracic procedures (T1-5), the head is placed in three-point fixation using Mayfield tongs (see Fig 53-1) to provide stability to the lower cervical and upper thoracic spine. Ophthalmic ointment is applied to the eyes, which are taped shut prior to prone positioning. If head tongs are not employed, plastic goggles may be utilized to minimize the risk of pressure on the eyes. Compression stockings and serial venous compression devices should be placed on the patient’s legs to reduce the likelihood of deep venous thrombosis and possible pulmonary embolus. In turning the patient to the prone position, care is taken to prevent twisting the neck. The patient is log-rolled onto soft bolsters that extend from the shoulders to the pelvis, allowing the weight to be carried at these four points and allowing the chest to expand and the abdomen to be free from compression. The skeletal head holder is positioned so that the cervical spine is mildly flexed (“military position”). All bony prominences, particularly the elbows, are padded, and the arms are tucked to the side. Exposure can be facilitated by using 3-inch-wide adhesive tape to depress the shoulders by extending the tape from the tip of one shoulder to the opposite side of the table in a crisscross fashion, ensuring that the cross occurs at the thoracolumbar region and does not involve the upper thoracic region. Care must be exercised to avoid extreme shoulder depression, which can produce a traction injury to the brachial plexus. The operative table is then tilted in a mild, reverse Trendelenburg position to elevate the head in relation to the feet and to place the upper thoracic vertebrae parallel to the floor (see Figs. 53-1 and 53-2B).

Positioning for lumbar spine exposure may be prone, lateral decubitus position, or knee-chest position. Our preference is either the kneeling position on an Andrews operating table (see Fig. 53-3A) or modified kneeling frame (see Fig. 53-3B) or the knee-chest position. These positions avoid abdominal compression, thereby reducing epidural bleeding. It is important to check preoperatively that the patient is able to flex both hips and knees to 90 degrees. The kneeling types of positioning are generally not appropriate for patients who weigh more than 300 pounds because of the risk of pressure blisters on the knees with prolonged kneeling. For most adults, this is an excellent method of positioning for lumbar exposures. The authors have used this position without difficulty for many patients in the late stages of pregnancy. If the Andrews table is used, it is important to measure the chest-to-knee distance accurately before turning the patient to the prone position. As with all face-down positioning, eye protection is necessary, and venous compression stockings and alternating leg compression devices (pneumatic compression stockings) are important. The patient’s feet should be padded before they are placed in the stirrups of the Andrews table. As the patient is being slid into the knee-chest position, it is important to keep sliding until the thighs are flexed 90 to 95 degrees. The buttocks board should be placed high on the buttocks so that it does not compress the sciatic nerves in the upper thigh. The arms are abducted 90 degrees at the shoulders, and the elbows are flexed 90 degrees, with padding of the axilla and the elbow to prevent peripheral nerve compression.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree