55 Lumbar Disc Arthroplasty

Indications and Contraindications

KEY POINTS

Introduction

Total disc replacement (TDR) surgery began in Europe over 20 years ago and migrated to the United States in 2000 with the first TDR Food and Drug Administration (FDA) Investigational Device Exemption (IDE) trial of the Charité III disc. Results based on the long-term follow-up from European literature have been promising so far, as have the early results from our U.S. experience.1–5 Some of the first 5-year follow-up data from the FDA IDE trial comparing the Charité disc to lumbar fusion are now available.6 The results show no statistically significant differences in outcome measures (visual analog scales (VAS) assessing pain and the Oswestry Disability Index) between the groups at the five-year mark, substantiating the noninferiority of the disc arthroplasty group. Additionally, the Charité patients had a statistically greater rate of part-time and full-time employment and a lower rate of long-term disability at 5years. Furthermore, the range of motion of the prosthesis, as evaluated by radiographic criteria, remained the same at 5-years compared with the 2-year data, showing preservation of motion at the surgical level.

At the time of writing of this chapter, a recently published systematic review analyzing the association of symptomatic adjacent segment disease (as distinguished from asymptomatic adjacent segment degeneration) in lumbar arthroplasty compared to arthrodesis showed that 14% of arthrodesis patients developed adjacent segment disease, compared with 1% of arthroplasty patients.7 Given this positive trend for arthroplasty, it is reasonable to assume that disc replacement surgery will remain a valid tool in the spine surgeon’s armamentarium and will likely become more prevalent in years to come.

Clinical Practice Guidelines

Indications

The established indication initially set forth by the FDA IDE studies for lumbar disc arthroplasty is severe unremitting low back pain resulting from single-level degenerative disc disease that has failed to respond to a prolonged course of conservative measures. The trial period for conservative treatment is usually defined as a minimum of 6 months, although the exact time frame itself is less important than the extent to which nonoperative management has been attempted. Nonoperative treatments should incorporate the use of various antiinflammatory, nonnarcotic, and even narcotic medications if necessary; physical therapy, including active exercise and core stabilization; chiropractic modalities; and a trial of spinal injections, including epidural injections and facet injections as appropriate. The purpose of these conservative efforts is to ensure that the patient has been afforded every opportunity to obtain a satisfactory result without surgery. We know that MRI alone is not a reliable indicator in predicting whether a degenerative-appearing disc is truly symptomatic.8,9 In some cases, discography may be helpful in delineating whether the disc is responsible for the patient’s clinical symptoms. The exact role for discography as part of the clinical work-up for potential surgical candidates is not clearly established, and is still an issue of significant controversy. That being said, at our institution we incorporate the use of discography in all patients that we feel might be appropriate candidates for total disc replacement. Because the interpretation of results from discography can heavily depend on the skill of the technician performing the procedure, the established relationship between the surgeon and the physician performing the test cannot be overemphasized. In our opinion, a poorly-done discogram is worse than no discogram at all.

Clinical Case Examples

Case 1

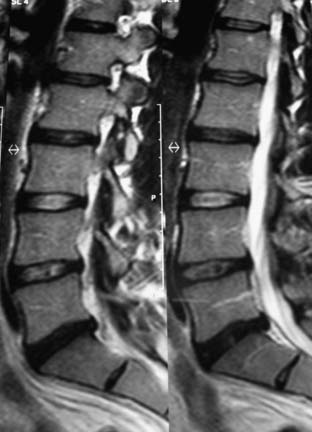

A 54-year-old woman presents to your clinic with complaints of severe low back pain that has progressed over the past 2 years. She has been through physical therapy focusing on core muscle strengthening and has had a trial of epidural steroid injections and various facet injections that did not improve her symptoms. She denies any radicular leg pain, but states that her low back pain is constant and is aggravated by prolonged standing, sitting, or walking. She has been on NSAIDs for the past few years, and has recently started to take narcotics because of increased pain. A complete neurological examination reveals no motor or sensory deficits. She has pain and limited motion with forward flexion of her lumbar spine. Her radiographs (Figures 55-1A and B) show normal spinal alignment with decreased disc space height at the L4-5 and L5-S1 level. No instability is present on flexion-extension views. A T2-weighted MRI (Figures 55-2A and B) reveals a dessicated L4-5 disc with preservation of hydration in the remaining lumbar discs. Given this scenario, what treatment option(s) would you discuss with this patient?

FIGURE 55-1 A and B. AP (A) and lateral (B) radiographs showing disc space narrowing at L4-5 and L5-S1.

Case 2

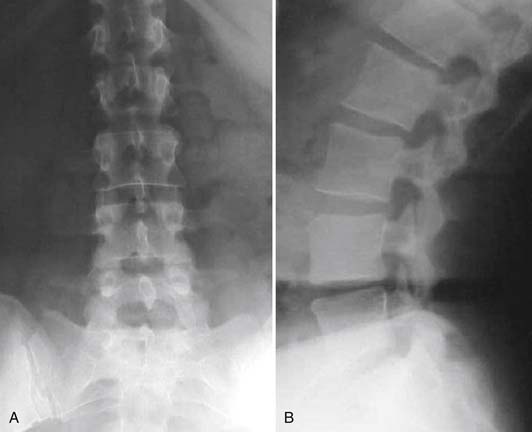

A 56-year-old male presents to your clinic for evaluation of debilitating low back pain over the last 6 years. He reports daily pain that radiates across his low back, worse on the right side. His primary care physician sent him to physical therapy for 6 weeks, but he did not see any symptomatic improvement. He has been taking hydrocodone for the past 6 months in order to bring his pain to a tolerable level but is frustrated by the need to be on narcotic medications and wishes for something to be done surgically to address his pain. His physical examination is fairly unremarkable and he has normal motor and sensory function. His plain radiographs reveal only minimal narrowing at the L4-5 and L5-S1 levels (Figure 55-3A and B). A T2-weighted MRI reveals pronounced desiccation with a small posterior bulge, along with minimal disc desiccation at the L4-5 level (Figure 55-4). On axial MRI views, the facet joints at both levels appear normal or with minimal degenerative changes. He asks whether he is a candidate for the disc replacement surgery. What do you tell him?

FIGURE 55-3 AP (A) and lateral (B) radiographs showing only minimal disc space narrowing at L4-5 and L5-S1.

Bertagnoli and Kumar stratified indications for disc arthroplasty into four categories based on remaining disc height, status of the facet joints, adjacent level degeneration, and stability of the posterior elements.10 The prime candidate for a disc replacement, based on their evaluation of clinical outcome in 108 patients who underwent implantation of a ProDisc II prosthesis, had at least 4 mm of remaining disc space height, no radiographic changes suggestive of facet arthritis, no adjacent level disc degeneration, and intact posterior elements.

Certainly, having competent, nondegenerative facets and posterior element stability are important inclusion criteria for a patient to be considered appropriate to undergo TDR. We will discuss the issue of facet arthrosis further as a part of contraindications to disc arthroplasty, but as far as a clinical evaluation is concerned, facets should be assessed with direct palpation and by having the patient demonstrate whether spinal extension (i.e., facet loading) reproduces pain. Radiographically, the facets should be evaluated by examining their appearance on plain films, CT scans, and/or axial MR images. There exist a few grading systems for facet joints, although none has gained universal acceptance. The first, proposed by Pathria, assigned a grade of 0 to 3, depending on the extent of facet joint narrowing.11 A “normal” facet joint is given a grade of 0, whereas a grade 1 is assigned for mild narrowing, 2 for moderate, and 3 for severe narrowing. Patients with grade 3 facets in this grading system should be excluded as candidates for disc arthroplasty. Fujiwara also proposed a grading system based on evaluation of the facet joints as they appear on axial MR images.12 In this system, a grade of 0 is again assigned to “normal” facets, grade 1 for moderately compressed facets with small osteophytes, grade 2 for facets with subchondral sclerosis and moderate osteophytes, and grade 3 for facets lacking articular joint space and with large osteophytes. Again, patients who meet the criteria for grade 3 facets in this classification system are not indicated for total disc arthroplasty.

Concern over the relationship between preoperative disc height and clinical outcome in disc arthroplasty with severely collapsed disc space (i.e., less than 4 mm) is somewhat controversial. Despite speculation that TDR is not appropriate for severely collapsed discs, there exist few data to support or refute this. At our institution, we set out to determine if there was a relationship between preoperative and/or postoperative disc height and clinical outcome at 2 years (Li, Guyer, et al., International Meeting on Advanced Spinal Techniques, 2008).13 For 117 patients (42 Charité and 75 ProDisc-L) undergoing a single-level TDR, we recorded disc height as a ratio of vertebral body height, thereby accounting for variation in individual size and radiographic magnification. Patients were categorized into four groups based on these ratios (most collapsed, second most collapsed, second least collapsed, least collapsed). For all groups, the mean VAS pain score improved significantly from preoperative values, but there were no statistically significant differences among the groups. We therefore concluded that there is no relationship between preoperative disc height and clinical outcome. If patients with severely collapsed discs otherwise meet the strict selection criteria for TDR, they can expect as favorable an outcome from the surgery as patients with discs that are not as collapsed.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree