29 Major Depression

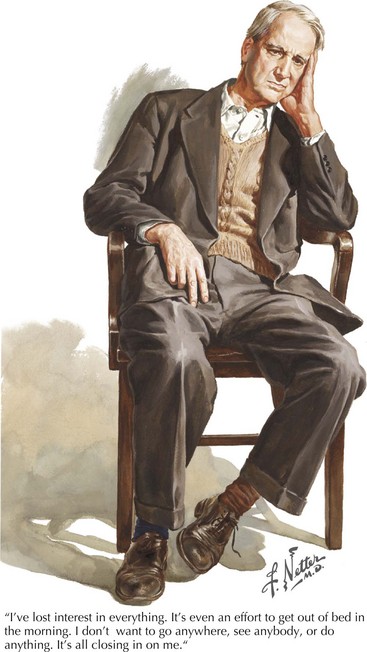

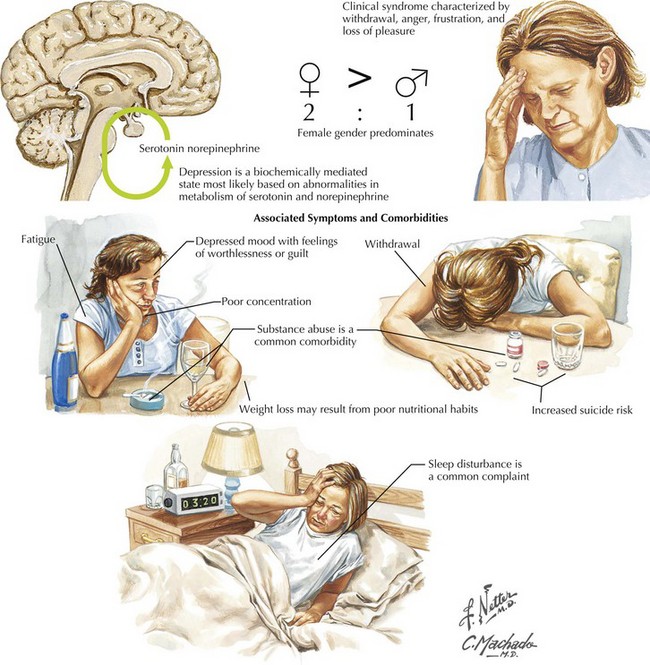

This vignette provides a classic picture of severe depression (Fig. 29-1). This is the most common serious psychiatric disorder; practicing physicians encounter it very frequently in many different guises. Depression is a very significant illness; it ranks second only to cardiovascular disease in overall morbidity and economic loss. Up to 20% of individuals within a general population will have at least one major depressive episode during their lifetime. Women have a higher incidence of depression between menarche and menopause, with an especially high risk postpartum. When depression affects men, the long-term risk of suicide is more common.

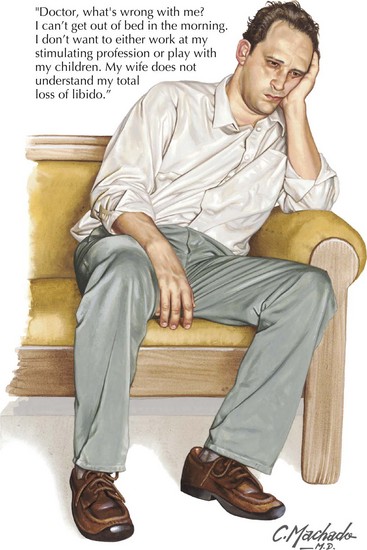

Depression usually begins in adolescence or early adulthood. It is a chronic illness with a propensity for recurrence. One common clinical pattern, called “double depression,” is characterized by repeated episodes of depression (Fig. 29-2) with eventual remission to a milder “dysthymic” state (Chapter 28). Familial clustering is apparent, although specific genes have not been identified. Depression beginning after age 60 years is probably a different disorder. It is less often associated with a significant family history but is associated with cerebrovascular disease and periventricular white matter abnormalities.

Clinical Presentation

One of the major medical concerns vis-à-vis any severely depressed patient is that suicide ideation and very definite attempts of the same are a common occurrence (Fig. 29-3). Although overt suicide attempts are notoriously difficult to predict, physicians must maintain a heightened sense of alertness to assessing suicide risk. One must always stand by to offer help and intervention per se when necessary, especially with the patient having significant suicidal risk factors. These include being a male, intense anxiety or agitation, social isolation, advanced age, history of previous suicide attempts, psychosis, and known alcohol abuse.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree