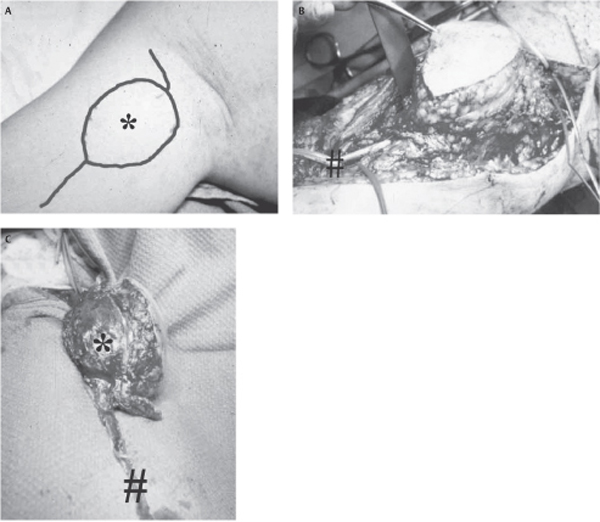

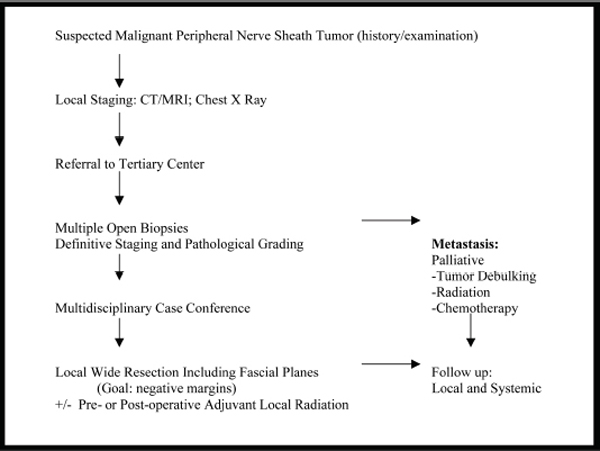

51 Management of Mallignant Peripheral Nerve Sheath Tumors A 23-year-old, right-handed woman presented with symptoms of a rapidly enlarging right axillary mass, of approximately 3 weeks’ duration. Her past medical history was remarkable for neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF1) diagnosed at age 7 years, when she presented with an asymptomatic mass in the right elbow, and the dermatological manifestations of NF1 were noted. She did not have a positive family history. At 19 years of age, she had a resection of a right forearm mass, which was arising from one of the branches of the lateral cutaneous nerve of the forearm and was pathologically verified as a benign plexiform neurofibroma. The patient had multiple café au lait spots, axillary freckling, and Lisch nodules observed in the iris. General motor, sensory, and reflex examination was unremarkable in her extremities, except for a minimal reduction to light touch in the right lateral forearm. In the upper arm, a sessile 4 to 5 cm diameter mass was noted with the following characteristics: (1) it was mobile in the axial plane, perpendicular to the directions of the infraclavicular brachial plexus, but not in the longitudinal axis of the axilla; (2) it was soft but not compressible; (3) it was not pulsatile; (4) compression or tapping elicited pain on the right lateral aspect of the forearm. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) with gadolinium enhancement showed a lobulated 5 x 4 cm mass in the medial aspect of the right upper arm. This was hypointense on T1 with indefinite margins but no evidence of any acute hemorrhage. The mass was located superficial and in the subcutaneous space anterior to the biceps and separate from any neurovascular structures in the axilla. It was hyperintense (on T2) and enhanced inhomogeneously with gadolinium. A chest x-ray was read as normal, with no evidence of metastasis. An upper medial arm incision was used to expose the mass with minimal manipulation. As suspected by the imaging and clinical characteristics, we found the mass to be arising from a distal branch of the musculocutaneous nerve and to overly the biceps muscle. Four quadrant biopsies were taken, with the quick section confirming our suspicion of a malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor (MPNST). As discussed with the patient, further surgery was not undertaken until full pathological examination. The pathology was reviewed by a neuropathologist experienced in peripheral nerve tumors. A transition from the plexiform neurofibroma that had given rise to the MPNST was noted (Fig. 51–1). Based on a definitive pathology of an MPNST and a negative metastatic workup, a recommendation was made for local wide resection including the biceps and overlying subcutaneous tissues along facial planes. The MPNST, with a wide margin of the underlying biceps, the overlying subcutaneous tissue and skin island, and a 6 cm piece of the lateral cutaneous nerve of the forearm, from which the tumor was arising, was excised and sent to pathology (Fig. 51–2). On the deep surface the tumor and biceps were easily elevated from the median nerve. Multiple biopsies were taken from all quadrants, with special attention to the deep fascia on top of the median nerve to insure that tumor-free margins were obtained. Drains were inserted with multiple-layer closure of the wound. Figure 51–1 Pathological confirmation of malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor with adjacent plexiform neurofibroma (star) from which it originated. The tumor (arrowhead) is hypercellular with a moderate mitotic rate and was classified as a grade 1–2 as per the grading scheme utilized for soft tissue sarcomas. Postoperatively the patient had excellent function, other than the expected numbness in the lateral aspect of the forearm. There was grade 4 elbow flexion, which was undertaken by her brachioradialis muscle in the midprone position. External beam radiotherapy was administered 6 weeks after her oncological operation using an irregular calculation to determine the need to correct inhomogeneities. The reducing field technique was applied utilizing two field reductions to hone in on the tumor bed itself with a total of 66 Gy in 33 fractions administered. She improved functionally to the point that she was back to work in 6 months’ time and remains disease free after 40 months of follow-up. Figure 51–2 Steps in compartmental resection. (A) The skin incision extends proximal and distal to the peripheral nerve tumor, including the malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor (star) for exposure. (B) Tumor, overlying skin, and subcutaneous tissue, underlying the biceps muscle and nerve of origin (lateral cutaneous nerve of the forearm [≠]) are all carefully exposed. (C) Definitive oncological surgery involves removing the tumor (star) with overlying subcutaneous tissue, biceps and deep fascia with a long section of the nerve of origin (lateral cutaneous nerve of the forearm [≠]) en bloc. Multiple peripheral biopsies are taken to verify tumor-free margins. Malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor A rapidly growing lesion proximal to a previously operated site for a plexiform neurofibroma in an NF1 patient, with the clinical characteristics consistent with a peripheral nerve tumor, is highly suggestive of an MPNST. Although highly suspicious for an MPNST that has resulted from one of the sensory branches of the musculocutaneous nerve (given the location of the sensory findings), a wide differential diagnosis of a soft tissue mass needs to be entertained. Moreover, given the rapidity of growth, lymphadenopathy (infectious or neoplastic), a pseudoaneurysm, or a rapidly growing soft tissue sarcoma must all be considered. MPNSTs are rare tumors that remain incurable, mainly due to their high metastatic potential, and are managed by several surgical disciplines, including plastic, orthopedic, and neurosurgery, depending on local interest and expertise. The rarity of MPNSTs usually renders them to be managed as per clinical protocols utilized for the much more common soft tissue sarcomas (STSs), of which MPNSTs represent between 3 and 10% of all such tumors. Whether these protocols can also be extrapolated as being the most appropriate for MPNSTs remains uncertain, but their low incidence prevents adequate experience as to their optimal management by one single center. The hypothesis that MPNSTs are not the same as other STSs, both clinically and on a molecular basis, is most clearly exemplified by 50% of all MPNSTs occurring in the context of the germline cancer predisposition syndrome, NF1. Indeed, NF1 patients harbor a 3 to 5% risk of conversion of the larger proximal plexiform neurofibromas to an MPNST, a point that has to be remembered in the long-term management of these patients, which represent the most common cancer predisposition syndrome in humans. Although the foregoing discussion points out potential differences between MPNSTs and STSs, the reality remains that this rare tumor is ideally managed by a multidisciplinary team, with much of the management strategy borrowed from the literature dealing with STSs. The management of MPNSTs that we adopt is summarized in Fig. 51–3. It involves local staging by means of computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), followed by biopsy and referral to a tertiary center, then followed by pathological grading and metastatic survey. From here the case is discussed in a multidisciplinary conference leading to local treatment with wide resection (the goal of obtaining negative margins) plus or minus adjuvant radiotherapy. The patient will then be followed up at close intervals with both clinical and radiological surveillance, looking for evidence of local recurrence or distant dissemination. Prior to oncological surgery, whose goals are to obtain a negative margin and provide the best chance for local control, a further metastatic survey including a CT or MRI scan of the chest is undertaken. For patients presenting with metastasis, palliative radiation locally and to systemic metastasis, combined with chemotherapy and occasional surgery, is the usual course, though with limited long-term control. Most patients, however, do not have metastasis upon presentation, and in these cases the aim of surgery is wide oncological resection with negative tumor margins to obtain local tumor control. Sarcomatous cells are found to spread extensively within the fascial planes, resulting in high recurrence rates and ultimate systemic spread following simple excision of the tumor alone. This has led to the adoption of aggressive oncological surgery in an attempt to maintain local control, if the preoperative metastatic workup is negative. Initially, such surgery involved limb amputation and disarticulation; however, our center and others have found wide oncological resections incorporating not only the tumor but also adjacent fascial and muscle planes (Fig. 51–2) in conjunction with either or both neoadjuvant and adjuvant radiation or chemotherapy, to achieve the same goals without necessitating sacrifice of the limb.

Case Presentation

Case Presentation

Diagnosis

Diagnosis

Characteristic Clinical Presentation and Differential Diagnosis

Characteristic Clinical Presentation and Differential Diagnosis

Management Options

Management Options

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree