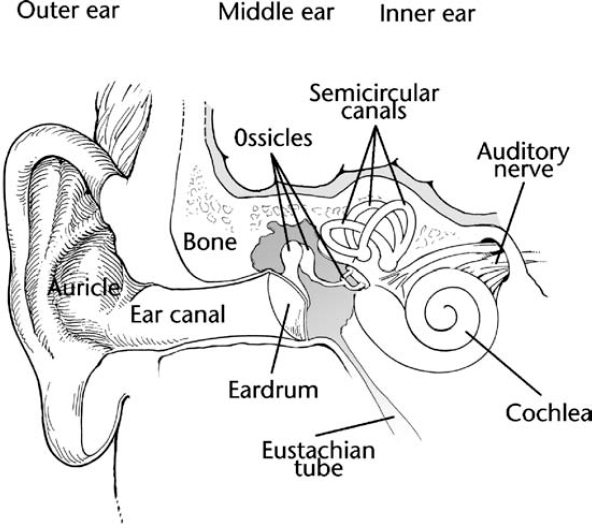

11 A diagnosis of confirmed or probable neurofibromatosis 2 (NF2) raises a host of new challenges. Optimal management of the disorder depends on several variables, including the individual’s age, family history, symptoms, and comfort with risk. Problems with vision are best treated early, but that is not always the case with tumors. Because the tumors associated with NF2 are usually slow growing, treatment decisions are complicated. The patient and physicians together must weigh the risks and benefits of treatment carefully, including the timing of intervention and the type of surgery chosen. The risk/benefit ratio also depends on the type of tumor being discussed. Early intervention might be proposed in treating vestibular schwannomas, for instance, to increase the chances of hearing preservation. A strategy of watchful waiting might be more appropriate for other sorts of brain and spinal tumors associated with NF2. In general, optimal management in NF2 should take place at a specialty clinic and consists of anticipatory screening for people with confirmed or probable diagnoses who remain asymptomatic. Such screening may occur more frequently when a person is first diagnosed, to determine how quickly tumors are growing. In most people annual follow-up evaluations are sufficient, following the guidelines in Chapter 10. This chapter reviews the issues and options that arise when manifestations develop. The hallmark tumors of NF2, vestibular schwannomas, eventually require treatment in most cases. The decision about whether to perform surgery depends on several factors such as the age of the person and the rate at which the tumors are growing. Vestibular schwannomas can eventually grow so large that they engulf the eighth cranial nerve, resulting in hearing loss and other complications. They can also damage other cranial nerves and cause facial paralysis, brainstem compression, and ultimately even death. A key challenge is to decide how early to intervene and what technique to use. In the past, concern about the risks of surgery–which could itself cause hearing loss–convinced many surgeons that the best strategy was to wait until the tumors grew large enough to cause significant hearing impairment before removing them. With the advent of improved imaging and surgical techniques, opinion on this matter is changing. Many experts now recommend a more proactive approach, with intervention initiated early in an attempt to preserve hearing. It is important to note, however, that the issue remains controversial and the exact strategy chosen involves an individual assessment of risks and benefits for each individual case. Management options for vestibular schwannomas now fall into three broad categories: surgical removal, radiation, and monitoring. There are several surgical options, depending on tumor size and extent of hearing loss. Some techniques preserve the auditory nerve and enable the patient to retain some hearing; others may sacrifice the nerve but are combined with insertion of an electronic auditory brainstem implant to restore hearing. In general, people with small vestibular schwannomas (defined as less than 1.5 cm) that are contained within the internal auditory canal are likely to retain hearing following total surgical removal of the tumor.1,2 Recommendations vary about how to treat people with larger tumors who still retain some functional hearing. Some experts recommend partial tumor removal to preserve hearing,3 whereas others think that total tumor removal is appropriate for people with tumors less than 2.5 cm in diameter, as long as it is done in a way to preserve hearing.4 (The surgical options are explained below.) If a person has bilateral tumors and still has functional hearing, one tumor may be treated first and the results assessed 6 to 12 months later. This allows time to see whether hearing was preserved in the treated ear before intervention decisions are made about the remaining ear. If hearing has been lost in the treated ear, patient and physician may decide on a strategy of watchful waiting to preserve hearing in the remaining ear for as long as possible.5 Total tumor removal is accomplished by several techniques. People who have sustained significant hearing loss may undergo translabyrinthine craniotomy. This procedure removes the auditory nerve along with the tumor, causing complete deafness in the ear. In some people, hearing may be partially restored by implanting an auditory brainstem implant. The suboccipital approach is generally used for people whose tumors have not yet extended into the internal auditory canal. The middle cranial fossa method may be best for people with small tumors and functional hearing; it results in hearing preservation in a significant number of people.4 Partial tumor removal, also known as decompression, may be an option for people whose tumors are being monitored and who are experiencing fluctuations in hearing. The usual technique is the middle fossa approach, which involves the removal of some bone and tissue so that the tumor can continue to grow without compressing the cochlear and auditory nerves. This restores hearing in some people, at least temporarily. Generally this procedure is not recommended, however, because eventually another operation must be done to remove the tumor, and long-term risk of hearing loss is about the same as in total tumor removal.4 Although surgical techniques have improved significantly in recent years, risks remain. Sometimes facial nerves are damaged during surgery, causing temporary or permanent numbness and drooping (palsy) on one side of the face. This can cause additional consequences, such as corneal damage due to an inability to blink, or trouble chewing food. Some people also experience temporary or chronic headaches following brain surgery. Radiation therapy has also improved with the advent of stereotactic devices, such as the gamma knife, that enable radiosurgeons to precisely target the tumor while sparing surrounding healthy tissue. In radiation therapy, high-energy x-rays damage genetic material in cells so that they can no longer divide and multiply. These damaged cells eventually die. Stereotactic radiosurgery is based on the same principle, but enables multiple beams to converge on the tumor from different angles. This increases total dose delivered to the tumor while minimizing the amount that spills over into surrounding tissue. Radiation therapy does not completely destroy the tumor, but it may shrink it and prevent or retard further growth. This allows hearing preservation in many people. Although sometimes viewed as a “miracle” treatment, radiotherapy is not appropriate for every patient. In some circumstances, radiotherapy may provide an additional treatment option, especially for people who do not want to undergo conventional surgery or are not eligible for it because of age, medical history, or some other reason. A risk to consider is that any radiation treatment may initiate a malignant transformation in the treated tumor. Once the mainstay of management for vestibular schwannomas, a strategy of watchful waiting is now reserved only for selected individuals with NF2. These include people who are unlikely to benefit from attempts at hearing preservation, individuals who have already lost hearing in one ear, and patients who are too old or ill to tolerate surgery. The person in question should undergo a magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan annually to monitor growth and progression of the tumor. Surgery is initiated once hearing is lost or the tumor becomes so large that it threatens further disability. The person who sustains significant or total hearing loss may be devastated. Given the risks that some degree of hearing loss may occur in NF2, even after vestibular schwannomas are treated, it is wise to discuss what options are available besides an auditory brainstem implant. Lip reading and sign language are two longstanding alternatives. Both techniques are easier to learn while some functional hearing remains. Any patient who is experiencing hearing loss and/or considering treatment of vestibular schwannomas should ask for a consultation with an audiologist to review all the options and decide whether to begin training in lip reading or sign language. Although loss of hearing is often a primary concern for people with NF2, anyone with vestibular schwannomas should also receive counseling about the potential challenges posed by loss of vestibular nerve function. This includes dizziness, unsteadiness while walking, and disorientation while under water. The last point is exceptionally important; some people with bilateral vestibular schwannomas have drowned while swimming.6 People with NF2 should not take up diving and should swim only when accompanied by others. Some surgical techniques to remove vestibular schwannomas sever the auditory nerve. When this occurs, an electronic device known as an auditory brainstem implant may restore partial hearing in some people. Conventional hearing aids and cochlear implants are not effective. To understand why, it is first necessary to understand how people hear (Fig. 11–1). Sound travels into the outer ear to the eardrum, which vibrates in response. Three small bones in the middle ear known as ossicles (the anvil, hammer, and stirrup) start to move as a result, and they convert sound waves into mechanical pressure that is then conveyed to the fluid filled cochlea. As the fluid begins to move, tiny hairs in the cochlea send electrical signals to the brain via the auditory nerve. Conventional hearing aids amplify sounds sent to the eardrum. These may be useful early on, when vestibular schwannomas cause limited hearing loss, but will not be helpful over the long term. Cochlear implants bypass damage in this part of the inner ear and directly stimulate the auditory nerve. Neither is effective if the auditory nerve itself is damaged or severed. The auditory brainstem implant is an electronic device implanted on the surface of the cochlear nucleus in the brainstem, thereby bypassing the inner ear. Instead, sounds are sent from the brainstem to the brain.

Management of Particular Neurofibromatosis 2 Features

♦ Vestibular Schwannomas

Surgery

Radiation

Monitoring

Counseling

♦ Hearing Implants in Neurofibromatosis 2

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree