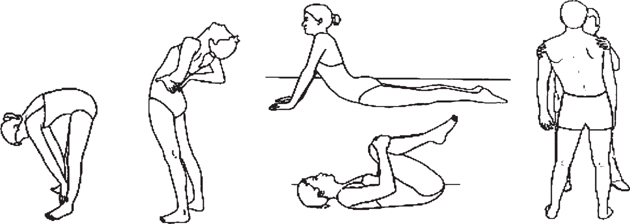

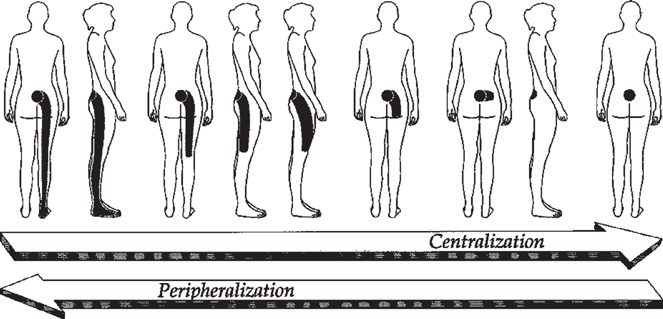

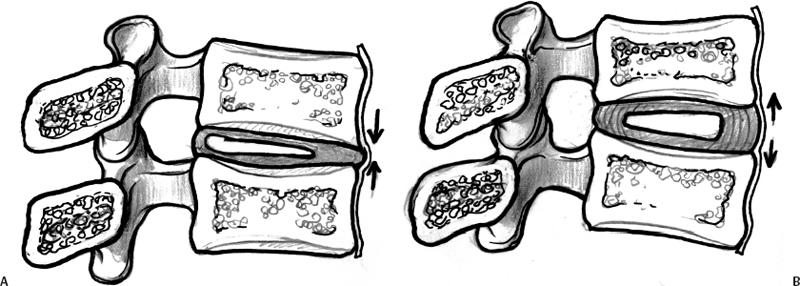

17 Mechanical Diagnosis and Therapy Ronald Donelson Selecting the appropriate nonoperative treatment for low back pain (LBP), with or without sciatica, or selecting appropriate patients for lumbar disc surgery are two critical decision points in the management of this common and expensive health care challenge. The lack of reliable correlation between clinical signs and imaging complicate these decisions as well as contribute to the high variability in the meaning of the phrase “exhausting conservative care,” a routinely stated prerequisite to considering surgical intervention. This is all reflected in the 8-fold difference in the rate of lumbar discectomies and the 20-fold difference in fusion surgeries across the United States.1 This chapter serves as an important bridge between the preceding section dealing with assessment methods for degenerative disc disease (DDD) and the chapters that follow targeting the treatment of DDD. The important assessment phase of mechanical diagnosis and therapy (MDT), though often misunderstood and certainly underutilized, enables clinicians to first determine the presence or absence of an absolutely unique feature of LBP disorders, whether or not the pain of DDD and herniated discs is rapidly reversible or not (a topic well covered in a recently published book).2 For individuals with a rapidly reversible condition, this assessment also identifies the means to eliminate these reversible symptoms, correct and stabilize the pain-generating reversible pathology, and then prevent its recurrence. Over the past two decades, multiple studies have demonstrated the reliability and validity of this MDT approach in producing superior outcomes as well as in identifying the presence or absence of symptomatic discs and their reversibility, a dynamic quality that even our most advanced imaging technologies are unable to evaluate. Diagnosis of herniated, compressive disc pathology is precise and consists of a history of radicular pain, positive straight-leg-raising, positive nerve root findings based on neural deficits, and objective demonstration of concordant pathology (e.g., computed tomography [CT] or magnetic resonance imaging [MRI] findings of herniated nucleus pulposus [HNP]). Surgical treatment then carries a high rate of success.3–7 Nevertheless, in light of good long-term outcomes with nonoperative treatment in this group6–8 the decision of whether to operate on this compressive form of lumbar disc disease carries its own challenges in the context of patients’ preferences for surgical versus nonsurgical care.9 The picture is far less clear in the setting of disc disease producing axial pain only. Based on the inability of conventional imaging techniques to identify such symptomatic levels,10,11 lumbar discography has become prevalent. Although many studies have reported discographic utility,12–20 more recent articles emphasize the importance of proper technique and recognition of confounding variables of psychological or occupational distress.21 Meanwhile, with highly variable rates of success reported following surgery for DDD,13,22–27 surgical selection criteria are obviously in need of refinement. The MDT form of assessment was brought to our attention by Robin McKenzie, a physiotherapist from New Zealand, in 1981.28 It is widely recognized that disc pain is commonly aggravated by positions and movements requiring lumbar flexion, but there are at least four randomized controlled trials (RCTs) that have actually reported on the interesting relationship between the direction of spinal loading and the distal extent and/or intensity of low back and leg pain.29–32 The authors of these articles related specific lumbar directional symptom responses directly to disc pathology29,30 or the extent of the distal spread of leg pain to the severity of that disc pathology. The MDT assessment also focuses on monitoring patients’ patterns of pain response (changes in pain intensity and location) first to positions, movements, and activities as reported in patients’ histories, but then also during each patient’s performance of a standardized sequence of repeated end-range spinal test movements and positions to the extent their pain permits (Fig. 17.1). It is as a result of performing these test movements that so many patients report that a specific direction of spinal movement promptly centralizes their referred or radiating pain, that is promptly decreases the extent of its distal radiation to a more proximal or central location, even fully abolishing the pain. This centralization pain response was first described by McKenzie in 1981 (Fig. 17.2).28,33,34 What is particularly intriguing is that centralization often persists after these test movements have been concluded, as though the pain generator has somehow been altered in some beneficial way. Particularly revealing are the many with pain radiating to the calf or foot with neural deficits where a single direction of end-range lumbar testing is found that promptly centralizes and then even eliminates their pain, revealing the means to a rapid and full recovery. Such rapid reversibility of patients with sciatica and neural deficits was documented in 32 patients in a 1986 cohort study that will be discussed later.35 Fig. 17.1 Most common forms of end-range lumbar testing included within the MDT physical examination process: standing flexion, standing extension, supine flexion, supine extension, and standing lateral-gliding. Lateral testing is also conducted with the subject lying prone by manually shifting the hips laterally maximally to the right or left. The test movements themselves are performed repetitively while monitoring the patient’s report of a pain response. Sitting flexion or recumbent extension or lateral loading are also commonly tested and informative test positions when monitoring pain response. Fig. 17.2 A decrease or abolition of the most distal extent of a patient’s pain is the first sign of centralization. If centralization continues with more repetitions of the beneficial direction of testing and all but midline pain is abolished, the pain is said to have fully centralized. When only midline pain is present, it too can often be intentionally abolished using either repeated flexion or extension testing, with the opposite direction of repeated testing typically making it worse or even “peripheralizing” the pain. (From McKenzie R. The Lumbar Spine: Mechanical Diagnosis and Therapy. Waikanae, New Zealand: Spinal Publications New Zealand Ltd; 1981; reprinted with permission.) Such a centralizing pain response indicates the likely presence of a discrete mechanical pathology and, more importantly, one that is rapidly reversible when addressed using a single direction of patient-generated repeated end-range spinal loading forces. This MDT assessment is well described.34 So let us now focus on the growing body of scientific literature that supports the widespread use of this MDT assessment. Over the past two decades, centralization and directional preference have been widely investigated, with most studies falling into three distinct and useful study designs. The value of any clinical test is fundamentally based on its interexaminer reliability. There can be no validity without this reliability. Spratt et al36 were the first to report strong reliability for conducting repeated end-range test movements, concluding that this assessment provided useful diagnostic information and was helpful in identifying the most efficacious form of physical therapy for patients with nonspecific LBP. Many more studies have since similarly reported high reliability of well-trained examiners in determining the presence or absence of the centralization pain response and in categorizing patients into the MDT classification scheme.37–41 One study supported the importance of examiner training by showing that those with little formal MDT training had poor interexaminer reliability.42 Multiple cohort studies have reported on the high prevalence of centralization, elicited in 73 to 89% of acute LBP patients41,43–45 and in 45 to 52% of chronic LBP patients.46,47 One RCT studied acute, subacute, and mostly chronic patients reporting a directional preference prevalence of 74%.48 Even patients with sciatica and neural deficits often have a directional preference (DP).35,48 In each of these cohort studies, centralizing patients with a DP reported significantly better outcomes than those of noncentralizing patients. Indeed, all patients in the sciatica cohort with neural deficits and a DP recovered full lumbar motion and eliminated all their pain within 5 days of commencing directional exercises as directed by their lumbar testing.35 One acute LBP cohort (N = 223) reported that the presence or absence of centralization during the baseline assessment was far superior in predicting one-year outcomes than 23 other baseline variables, including psychosocial factors often reported as outcome predictors.49 Specifically, both good and poor one-year outcomes were much better predicted by the presence or absence of centralization than by psychosocial factors. Four RCTs have so far investigated this large subgroup whose pain centralizes with a DP at baseline.48,50–52 All four reported superior outcomes when treatment was matched to baseline findings versus other forms of treatment. One study specifically showed superiority in treating this subgroup with MDT principles rather than by current LBP clinical guidelines’ treatment.48 Although contradicting our conventional thinking about LBP, but of great importance, when pain centralizes and/or abolishes with a directional preference, one still-to-be published study confirms other cohort reports that it does not matter whether pain is acute or chronic, or whether axial or sciatica with neural deficits, these patients, properly treated, do very well.48 In terms of predicting outcomes, the evidence so far is that LBP with a DP usually trumps pain duration, pain location, neural status,48 as well as psychosocial factors49 by routinely recovering rapidly. No single clinical finding or physical sign has been shown to be pathognomonic of discogenic pain. However, a growing number of studies suggest that centralizing pain strongly correlates with symptomatic disc pathology,41,43–47,49 helping to document the significant usefulness of the MDT assessment in clinical decision making.35,46 Numerous cadaveric,53–55 discographic,56 and MRI57,58 studies document the posterior migration of nuclear content in response to anterior disc loading that occurs with lumbar flexion and the resulting anteroposterior pressure gradient across the disc. The direction of this gradient can then be intentionally reversed with posterior loading that occurs with lumbar extension creating anterior nuclear migration (Fig. 17.3).59 With nociceptors in the outer third of the anulus as a common source of pain,60–62 it is then quite plausible that flexion may create tension and fissuring of the posterior anulus coupled with the posterior migration of nuclear contents down a fissure enabling the stimulation of mechanoreceptors in the outer anulus. 2,34,46,58,63

Current Criteria for Surgery and Outcomes

Mechanical Diagnosis and Therapy

Assessment

Scientific Evidence for Efficacy

Interexaminer Reliability

Observational Cohorts

Randomized Clinical Trials

A Dynamic Internal Disc Model for Rapidly Reversible Lower Back Pain

Directional Nuclear Movement

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree