Chapter 6 Medications used for substance use problems

The information in this chapter will assist you to:

Introduction

In many countries, a number of substances, illicit and legal, are used for recreational purposes. Common reasons why these substances are taken include to induce pleasure and euphoria, provide relaxation, relieve stress or escape the negative feelings associated with mental illness; they may be taken as part of lifestyle experimentation or to achieve acceptance within a peer group. As noted, use becomes misuse when repeated administration becomes problematic, increasing the chances of illness, job loss, arrest and failure in life roles. Prolonged misuse can lead to dependence, where persistent, compulsive and uncontrolled use continues in spite of these problems, leading to maladaptive and destructive behaviours (Hyman 2005, Adinoff 2004). Drug dependence can trigger a withdrawal syndrome, which is characterised by physical discomfort and drug craving, when the use of the substance decreases or stops. The link between misuse and dependence, however, is not necessarily clear. A person’s substance misuse does not always progress to dependence, and research indicates that the intake of some substances that have the potential for dependence (e.g. cocaine, heroin) does not automatically lead from one state to the other (Ridenour et al 2003).

Commonly misused substances include tobacco (nicotine), alcohol, narcotics, amphetamines, cocaine, marijuana, ecstasy and related drugs, hallucinogens, benzodiazepines and inhalable solvents. As noted, these substances can be broadly grouped under two headings – licit (or legal) and illicit/illegal substances. In Australia, the most commonly misused legal substances include alcohol and tobacco. In 2004, the most commonly used illicit drug in Australia was cannabis, with 1 in 3 people (34%) having used it during their lifetime, and 11% of the population having used it during that year. Methamphetamine had also been used by 9% of Australians over the age of 14, with 3% having used it within that year (AIHW 2007). A summary of recent Australian and New Zealand statistics on drug use is provided in Table 6.1.

Table 6.1 Recent regional statistics on substance use

Adapted from Statistics on drug use in Australia 2004, 2005, by the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, AIHW Cat No PHE 62, AIHW [Drug Statistic Series No 15] and New Zealand Drug Statistics, 2001, by the New Zealand Health Information Service, New Zealand Ministry of Health

Substance use and mental health – dual diagnosis

With respect to mental health, substance use and misuse are important issues. Dual diagnosis, or co-morbidity, refers to the presence of both a substance use problem and a mental health problem. Prevalence rates for co-existing problems indicate that between 35% and 60% of people with mental health problems also have a substance use issue (Mueser et al. 1995 and Menezes et al 1996 in Rassool 2006). The links between substance misuse and mental health are complex, where one may be considered the ‘primary’ problem and the other ‘secondary’. Often, however, it is difficult to determine which problem came first. What is important is that both the substance use problem and the mental health problem are addressed because, if only one is treated and not the other, the consumer is much less likely to recover from either issue.

Substance use that has been particularly linked with mental health includes that of cannabis, and this is especially so for young people. There is considerable evidence that frequent use of cannabis may be predictive of a higher risk of developing psychotic symptoms (Hall 2006). Regular (i.e. daily–weekly) cannabis use has also been linked closely with the development of mental health problems such as depression and bipolar disorder (van Laar et al 2007). Research has also revealed that consumers with psychotic mental health problems such as schizophrenia and bipolar disorder show a significantly higher lifetime prevalence of illicit substance use, particularly of stimulants such as amphetamine and cocaine, than the general population (Ringen et al 2008).

Pathophysiology of substance use problems

Normally humans, like other animals, develop goals that contribute to survival – such as seeking out food, shelter and mating – and these biological goals are seen as natural rewards. Cognitive and experiential rewards are associated with friendship and social status (Kalivas & Volkow 2005).

According to the model proposed by Hyman (2007), rewards are seen as desirable; they make us feel good and we are highly motivated to pursue them. Learned associations in our environment become cues to predict the availability of these rewards and they, in turn, trigger behaviours directed towards achieving these goals. Over time an increase in frequency in these behaviours reinforces the learning. Within the prefrontal cortex, there is a weighting of our goals according to their relative importance. With reinforcement, the actions required to obtain a reward become automatic and very efficient via connections to subcortical structures. Hyman states that behavioural control is the domain of the prefrontal cortex and its connections to the thalamus and corpus striatum and is achieved by maintaining the goal representation over time, suppressing distraction and inhibiting impulsiveness.

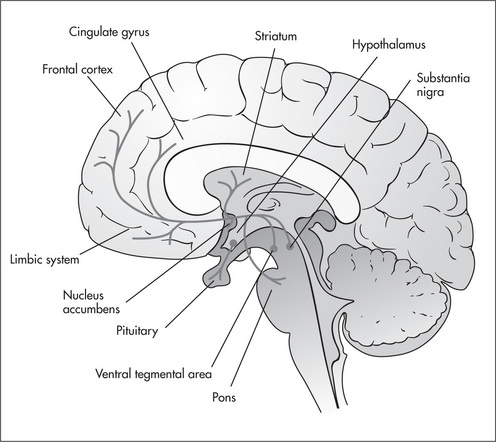

This circuitry is influenced by the activity of a dopaminergic modulatory system called the mesocorticolimbic pathway (see Fig 6.1). Dopamine is released from neurones in the ventral tegmental area (VTA) within the midbrain. These neurones project to a number of brain regions, in particular the amygdala, nucleus accumbens and prefrontal cortex, reinforcing a particular reward and altering the relative value of our other goals in relation to this one. An increase in dopaminergic activity signals that a reward is new or better than expected and this promotes learning. After repeated exposure the learned experience becomes very familiar and there is no increase in dopaminergic activity (Schultz et al 1997, Schultz 1998, 2006).

Figure 6.1 The mesocorticolimbic pathway.

Reproduced from Pathophysiology (3rd edn), 2005, by L C Copstead and J L Banasik, Elsevier-Saunders, Fig 43.32A, p 1077, with permission

As dependence develops, this process becomes pathological. The drug repeatedly increases dopaminergic transmission, reinforcing that the reward is better than expected. This pathological learning alters the importance of all goals established within the prefrontal cortex relative to wanting the drug and reduces behavioural control (Hyman 2007). Some substances, such as cocaine and the amphetamines, alter synaptic dopamine concentrations in the nucleus accumbens directly. Other substances act indirectly to increase synaptic dopamine levels via G protein-coupled receptors or ligand-gated ion channel receptors (Adinoff 2004) (see Table 6.2). Several neurotransmitter systems have been implicated along with dopamine in the reinforcing effects of drug use, including endogenous opioids, GABA and the endocannabinoids. Furthermore, regional changes in the levels of GABA, glutamate, serotonin, dopamine and nicotine have been reported in association with withdrawal of abused substances (Koob 2006). The compulsion to take drugs may be associated with reciprocal glutamatergic projections from the prefrontal cortex and amygdala, as well as from the prefrontal cortex to the nucleus accumbens and VTA, forming a repeating loop within the mesocorticolimbical pathway (Adinoff 2004) (see Fig 6.1).

Table 6.2 Substances that indirectly induce increased mesocorticolimbic dopamine levels

| Mechanism | Substance |

| G protein-coupled receptors | Tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) – active ingredient of cannabis |

| Opioids | |

| Caffeine | |

| Ion channel receptors | Alcohol |

| Phencyclidine (PCP) – an hallucinogen | |

| Nicotine |

From Adinoff 2004

There are a number of risk factors associated with substance misuse, including family history and gender (with males being at greater risk). Genetics also plays a role in determining the sensitivity of receptor systems, enzyme levels and metabolism that may contribute to a vulnerability to misuse substances. For example, there is evidence that the prevalence of particular genotypes associated with enzymes involved in alcohol metabolism within certain ethnic groups (for example, in South-East Asian people) may be protective against alcohol abuse and dependence (Moore et al 2007, Eng et al 2007).

An interesting area of research has developed to explore the basis of relapse, especially after an extended period of drug abstinence. It is proposed that dependence leads to long-lasting and stable remodelling of the brain circuits within the mesolimbic system. Two transcription factors, cAMP response element binding protein (CREB) and deltaFosB, that are responsible for the regulation of the expression of specific genes have become closely linked to chronic administration of addictive drugs because they can accumulate and persist in the prefrontal cortex and amygdala for an extended period (Nestler 2004). Nestler (2001) had already suggested that these factors may act as a switch that retains the connection between drug associated cues and reward long after drug use stops.