Chapter 4 Medications used for disturbances in mood and affect

The information in this chapter will assist you to:

5-HT 5-hydroxytryptamine (serotonin)

MAOIs monoamine oxidase inhibitors (antidepressants)

NSAIDs non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs

RIMAs reversible inhibitors of MAO-A

SARIs serotonin antagonists/reuptake inhibitors

SNRIs selective noradrenaline reuptake inhibitors

SSRIs selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors

Introduction

Across the Western world, mental health problems where mood and affect are major features (i.e., depression, mania and bipolar disorder) are highly prevalent and persistent and are associated with significant disability. While bipolar disorder and major depression are considered the more severe conditions associated with disturbances in mood and affect, other conditions of lesser intensity include cyclothymia and dysthymia. Perinatal mood disorders, including ante- and postnatal depression and puerperal psychosis, are also considered to be within the scope of disturbances in mood and affect and will be explored in further detail in Chapter 7. See Table 4.1 for an overview of the features of major disturbances in mood and affect.

Table 4.1 Major disturbances in mood and affect

| Disturbance in mood and affect | Features and symptoms |

|---|---|

| A major psychotic disorder that includes episodes of mania (elevated, expansive mood) and depression that can be of psychotic depth. Mixed episodes with both manic and depressed symptoms can also occur. Usually requires treatment with psychotropic medications | |

| A less severe mood disorder involving chronic fluctuation in mood, with episodes of hypomania (below mania) and depression that are not of psychotic depth. Does not necessarily involve treatment with psychotropic medications | |

| A less severe form of depression where the person has a chronically depressed mood for most days for at least a 2-year period. No symptoms of psychosis. May not require treatment with psychotropic medication | |

| Involves one or more episodes of moderate to severe depression that may be of psychotic depth, but no history of manic episodes. Main symptoms include depressed mood, lack of interest in pleasure (anhedonia), significant weight loss or gain, insomnia or hypersomnia, fatigue, feelings of worthlessness or guilt, reduced concentration, recurring thoughts of death and/or suicide. Usually requires treatment with psychotropic medication | |

| A form of major depression that can emerge within the first few weeks after delivery and up to six months after. PND can last for more than 2 years. Can require treatment with psychotropic medication | |

| This is a less prevalent form of mood disorder that can be experienced by some women postdelivery. Usually includes features of mania and/or depression and psychosis. The onset of PP is sudden and within 2 weeks of delivery. Usually requires treatment with psychotropic medications |

As discussed in previous chapters, the management of any mental health problem needs to address the individual’s overall situation and health care needs and, therefore, will usually include a range of treatment options where medication is one of a number of strategies. For moderate–severe disturbances of mood and affect, antidepressant medication and/or medications used to manage bipolar disorder are usually first-line treatments and often need to be taken on a continuing or long-term basis to prevent further episodes. However, medication is a strategy that can be offered in combination with individual and/or group therapies (e.g. cognitive-behaviour therapy), skills training (e.g. assertiveness training, stress and/or anxiety management techniques) and/or lifestyle changes including alcohol reduction, nutritional diet and regular exercise. This comprehensive approach generally provides the most effective management. If medication and/or other therapeutic options are not effective, somatic therapies such as electro-convulsive therapy or transcranial magnetic stimulation, particularly for treatmentresistant depression and/or acute suicidality, may be required.

Depression

Depression is characterised by symptoms that include intense sadness or loss of interests, along with fatigue, insomnia, changes in body weight, psychomotor agitation, feelings of worthlessness and suicidal intent. Depression is rated as one of the leading causes of non-fatal disease burden worldwide (AIHW 2006, Moussavi et al 2007). Indeed, in 1996 the Harvard School of Public Health projected that depression will become the second leading cause of disease burden after heart disease (cited in Moussavi et al 2007).

It is common, and indeed has been determined to be significantly more likely, for people with other chronic illnesses, such as heart and vascular disease, arthritis and asthma, to have co-morbid depression (AIHW 2006, Moussavi et al 2007). The degree of disability associated with depression is considered to be greater than that of arthritis, asthma, diabetes or angina and is believed to be associated, at least in part, with a poorer level of treatment relative to these physical disorders (Moussavi et al 2007, Andrews & Titov 2007). Depression is also significantly co-morbid with substance use disorders (e.g., alcohol misuse/dependence) and anxiety, and treatment and management of depression will often need to include assessment and management of these related conditions.

Bipolar disorder

Recent statistics from the USA have indicated that the 12-month prevalence of bipolar disorder is 2% of the population (Grant et al 2005). In bipolar disorder, people experience episodes of mania that alternate with periods of depression. For some consumers with bipolar disorder, there are more episodes of depression; for others, there are more episodes of mania. The symptoms of mania include euphoria or irritability accompanied by insomnia, impulsiveness, talkativeness, grandiose ideas, racing thoughts and ideas, distractability, increased sexual drive and increased motor activity.

In a recent review, Miklowitz and Johnson (2006) reported that bipolar disorder has a lifetime prevalence of around 4% and that it is equally likely to develop in men and women. However, women report more episodes than men. The first episode tends to manifest in adolescents and young adults and, like depression, bipolar disorder is highly likely to be comorbid with other conditions such as anxiety disorders and substance abuse. Bipolar disorder is also associated with higher rates of suicide than any other mental health problem.

Pathophysiology of disturbances in mood and affect

The noted British peer and pharmacologist, Susan Greenfield (2000), has articulated a useful perspective on the minds of people with mood disorders. In her book, The Private Life of the Brain, she suggests that people with depression become locked in highly personalised inner worlds that are colourless and muffled, where the outside world has less impact. For them, memories and events have exaggerated meanings and significance and this is correlated neurobiologically with neuronal associations, or circuits, that are overdeveloped and overused. People with mania become trapped in the present, overreactive to the outside world, readily distracted and hyperactive. She suggests that it is once again a problem of inappropriately sized neuronal networks. This time they are too modest. In bipolar disorder, when these networks are too small a compensation intervenes so that they rebound to become over-extensive, inducing depression, and then over-adjust back to being too small again.

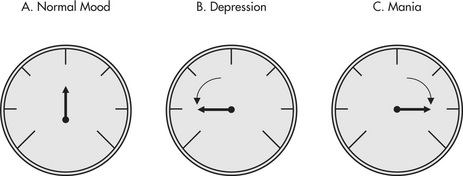

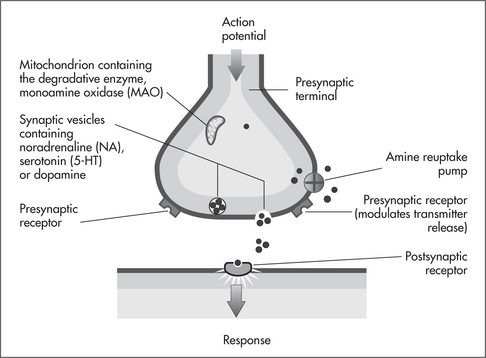

The accepted conceptual framework used to explain disturbances in mood and affect and provide a rationale for treatment with medication revolves around the biogenic amine hypothesis. It is proposed that these altered mood states are associated with an imbalance in the activity of the biogenic amine transmitter systems involving serotonin (5-HT), dopamine and noradrenaline (NA). In depression, the sensitivity of postsynaptic receptors is decreased, while in mania the sensitivity is elevated (see Fig 4.1). This hypothesis can also be used to explain how a person can cycle between depression and mania in bipolar disorder through changing sensitivities of these transmitter–receptor systems.

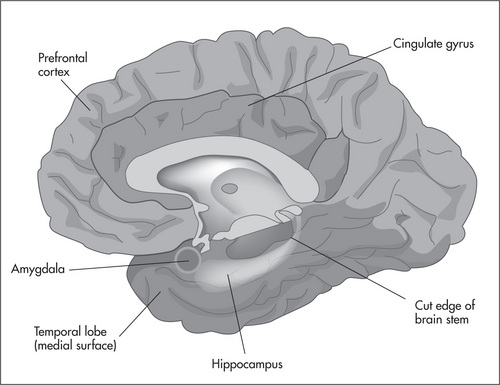

Recent research has indicated that endocrine and neurogenic factors may have significant pathophysiological roles to play in the development of these mood disorders. A loss of negative feedback control on the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal gland axis is considered a hallmark neuroendocrine marker in depression, leading to elevated release of corticotrophin-releasing hormone and glucocorticoids (Maletic et al 2007). Chronic stress or elevated glucocorticoid levels can lead to a loss of neurones within, and a decrease in volume of, the hippocampus. The hippocampus has a major role in the formation of, and access to, longterm memories and contributes in the control of emotions and behaviour. The hippocampus has connections to the amygdala and prefrontal cortex, areas of the brain that have been strongly implicated in the development of mood disorders. In addition to these areas, the basal ganglia and anterior cingulate may play a role in the pathophysiology of bipolar disorder.

In their review, Milkowitz and Johnson (2006) summarised the neurobiology of bipolar disorder. They report that dysregulation of the prefrontal cortex (shown to have a smaller than average volume in people with bipolar disorder), amygdala, hippocampus, basal ganglia and anterior cingulate causes a person who is manic to be less sensitive to negative stimuli, usually associated with threatening cues, and that increased reward motivation may be associated with hyperactivity of the basal ganglia. The brain regions involved in mood disorders are represented in Figure 4.2.

Figure 4.2 Brain regions implicated in mood disorders.

Reproduced from Neuroscience: Exploring the Brain, 2001, by M F Bear, M A Paradiso and B W Connors, Lippincott, Williams and Watkins, Fig 18.3, with permission

Chronic antidepressant therapy has been shown to enhance hippocampal neurogenesis. The increases in synaptic levels of serotonin and/or noradrenaline brought about by treatment are believed to trigger intracellular signalling cascades that regulate gene expression involved in neuronal function and/or morphology. The expression and actions of key neurotrophic factors that might facilitate this neurogenesis are currently being explored. Neurotrophic factors that have been implicated in this process include brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and cAMP response element binding protein (CREB) (Maletic et al 2007, Warner-Schmidt & Duman 2006). It has also been suggested that there is lateralisation of the control of affect at the hemispheric level, such that conditions that cause dysfunction of the left frontal hemisphere (e.g., a stroke in that region) can result in depressed mood (Shenal et al 2003).

Changes in intracellular signalling are also implicated in the cycling of mood states characteristic of bipolar disorder. For example, the Wnt intracellular signalling cascade appears to be disrupted in this condition. Some of the medications, such as sodium valproate, used to reduce the cycling have been shown to act on this cascade (Rosenberg 2007).

Pharmacology of antidepressants

Ostensibly, antidepressant medications act to raise the synaptic concentration of serotonin and/or noradrenaline. The mechanisms by which the medications can achieve this are by blocking the presynaptic re-uptake pump, inhibiting the enzymic degradation of the transmitter or inhibiting the presynaptic autoregulation of transmitter release (see Fig 4.3). Remember that the changes in synaptic transmitter levels may alter intracellular signalling cascades involved in neuronal function (see previous section). Second generation antipsychotics and antidepressant medications are two of the most commonly prescribed and administered classes of psychotropic medication (Reilly & Kirk 2007), with approximately 5–6% of adults being prescribed antidepressant medication to manage depression and/or anxiety (Mitchell 2007). The major uses of antidepressants are in the treatment and prophylaxis of major depression and the depressed phase of bipolar disorder. Other uses for antidepressants include the management of the anxiety disorders, which include generalised anxiety disorder, obsessive–compulsive disorder, social phobia and agoraphobia, as well for the eating disorder bulimia nervosa and for postpartum depression.

Figure 4.3 The mechanism of action of the antidepressant medications.

Reproduced from Fundamentals of Pharmacology (5th edn), 2007, by S Bullock, E Manias and A Galbraith, Prentice Hall, Fig 36.1, p 384, with permission

The major antidepressant medication groups used in this region of the world are described below according to their mechanisms of action. Generally, due to their tolerability and safety profiles, the prescribing of the newer selective serotonin re-uptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and selective noradrenaline re-uptake inhibitors (SNRIs) has to a large extent replaced that of the older antidepressant groups of tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs) and monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs). However, the latter two classes of medication are still used for a range of mood-related conditions.

Antidepressants that block re-uptake

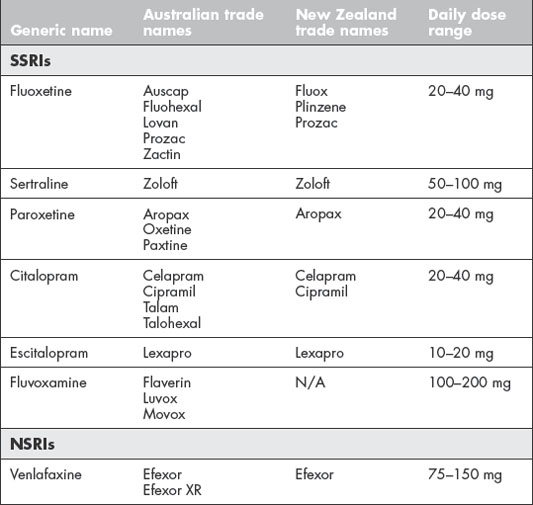

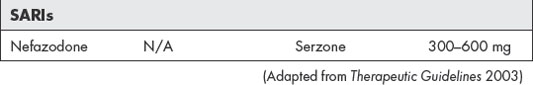

The SARI nefazodone acts to enhance serotonergic transmission through two mechanisms: an inhibition of serotonin re-uptake as well as a blockade of presynaptic 5-HT1 autoreceptors and postsynaptic 5-HT2 receptors. Common SSRIs, NSRIs and SARIs are listed in Table 4.2, and common TCAs are given in Table 4.3.

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree