59 Minimally Invasive Spinal Surgery (MISS) Techniques for the Decompression of Lumbar Spinal Stenosis

KEY POINTS

Introduction

Minimally invasive foraminotomies and discectomies have gained increasing popularity among spine surgeons for the treatment of herniated intervertebral discs. The minimally invasive miscroendoscopic discectomy has been particularly attractive for its small skin incision, gentle tissue dissection and excellent visualization. The technique has been shown to provide symptomatic relief equivalent to that achieved with open discectomy, with significant reductions in operative blood loss, postoperative pain, hospital stay, and narcotic usage. The evolution of minimally invasive techniques has led to safe and effective applications for the treatment of LSS. The minimally invasive percutaneous microendoscopic approach for bilateral decompression of lumbar stenosis via a unilateral approach has been described for the treatment LSS and has been shown to offer a similar short-term clinical outcome as compared to open techniques with a significant reduction in operative blood loss, postoperative stay, and use of narcotics.1 This chapter reviews the pathophysiology of LSS; explains the rationale, indications and surgical techniques for minimally invasive LSS surgery; and presents our 4-year outcomes data.

Pathophysiology

The clinical entity of lumbar spinal stenosis is one that is familiar to almost all physicians who treat the elderly. From a pathophysiological perspective, lumbar stenosis typically results from a complex degenerative process that leads to compression of neural elements from a combination of ligamentum flavum hypertrophy, preexisting congenital narrowing (e.g., trefoil canal), intervertebral disc bulging or herniation, and facet thickening with arthropathy of the capsule soft tissues.2–4 With the unparalleled recent advances in imaging, it has become evident that the majority of these changes and thereby the neurological compression are typically seen at the level of the interlaminar window.2,5 These pathological changes are thus thought to be responsible for the clinical symptoms of lumbar stenosis. For these patients, the sine qua non feature of the history is low back and proximal leg pain that worsens with standing and walking and is alleviated by sitting and bending forward. Whether this phenomenon occurs as a result of direct neural compression or from secondary vascular ischemia of the nerve roots remains unclear. Nevertheless, this presentation of neurogenic claudication, anthropoid posture, and low back pain is becoming increasingly common as our population demographic grows older and older. Indeed, stenosis of the lumbar canal is now the most common indication for surgery of the spine for patients over the age of 65 years.6–9 This peak incidence in the geriatric population makes the surgical treatment of spinal stenosis particularly difficult because these patients are at significantly increased surgical risk because of their often poor medical condition.

Treatment Options and Guidelines

The traditional treatment of lumbar stenosis usually entails an extensive resection of posterior spinal elements such as the interspinous ligaments, spinous processes, bilateral lamina, portions of the facet joints and capsule, and the ligamentum flavum. Additionally, wide muscular dissection and retraction usually are required to achieve adequate surgical visualization. These classical operations of a wide decompressive laminectomy, medial facetectomy, and foraminotomy have been used for decades with a variable degree of success.8–11 Such extensive resection and injury of the posterior osseous and muscular complex can lead to significant iatrogenic pain, disability, and morbidity. Loss of the midline supraspinous–interspinous ligament complex can lead to a loss of flexion stability, thereby increasing the risk of delayed spinal instability.12,13 Extensive laminectomy can also be associated with significant operative blood loss as well as prolonged postoperative pain and weakness secondary to the extensive surgical dissection and muscle detachment. Such iatrogenic injury can lead to paraspinal muscle denervation and atrophy, which may correlate with an increased incidence of “failed back syndrome” and chronic pain.14,15 Because patients with lumbar stenosis are usually elderly and often medically frail, this delayed recovery can often result in significant morbidity. Deep venous thrombosis, pulmonary embolism, pulmonary atelectasis, pneumonia, urinary tract infections, ileus, and narcotic dependency are but some of these potentially devastating sequelae.

Whereas conservative therapy initially is a reasonable recommendation, there will inevitably be a significant proportion of patients with progressive stenotic symptoms who will ultimately require surgical intervention. In the Maine Lumbar Spine Study group, Atlas and coworkers16 prospectively followed 97 patients over a 10-year interval. Of these, 56 were surgically treated and 41 were conservatively managed. Based on patient satisfaction assessment vehicles, 54% of surgically treated patients reported improvement versus 42% of nonsurgical patients at 10 years. In comparison, the 4-year data from the Maine Lumbar Spine Study group revealed that 70% of surgically treated patients reported a clear improvement, compared to 52% in the nonoperative group.6 This decrease in patient satisfaction indicates that surgical benefits may not be stable over the course of time because LSS is typically a chronic and progressive disease. Hurri and colleagues,7 in 1998, reported their longitudinal 12-year study of 75 patients with lumbar stenosis. Using the Oswestry index, their disability was scored over many years and could demonstrate no clear difference between those who were operated on versus those managed conservatively. From an extensive review of the literature, Turner concluded from his attempted meta-analysis that approximately 64% of surgically treated patients had a good outcome over a midterm period of follow-up (3 to 6 years). However, he also noted that delayed clinical progression and recurrence of stenosis symptoms was extremely common, thus reflecting the chronic degenerative nature of the underlying disease process.13 Thus although surgical treatment appears to have a positive effect on the natural history of LSS, clinical progression and recurrence is likely. Moreover, several subgroups have been consistently identified that are particularly prone to recurrence of symptoms. These include patients with preexisting spondylolisthesis, scoliosis, prior destabilizing laminectomies, and the presence of segmental vertebral motion on flexion–extension radiographs.17,18 According to the treatment guidelines set forth by the AANS/CNS Joint section on Disorders of the Spine and Peripheral Nerves, fusion is recommended for patients with lumbar stenosis and associated degenerative spondylolisthesis who require decompression.19 In addition, wide decompressions leading to disruption of the facet joints has also been associated with poorer outcomes.19 In light of these considerations, the need for a less invasive means of decompression without major disruption of the facet joints and muscular attachments as well as the option of fusion for the treatment for LSS is evident.

Surgical Rationale

Over the past two decades, numerous surgeons have worked toward the goal of reducing the surgical morbidity of the procedure. The ideal operation for LSS would be one that could simultaneously achieve an adequate decompression of the neural elements, while at the same time minimize damage to the posterior muscular, ligamentous, and bony complex. Because the pathological changes typically are concentrated at the level of the interlaminar space, focal laminotomy was the natural first step in the evolution of surgical procedures for LSS. By sparing most of the lamina, spinous processes, and interspinous ligamentous complex, laminotomy helped to preserve the biomechanical integrity of the spine. Aryanpur and Ducker,20 in their description of multilevel open lumbar laminotomies, reported a longitudinal good outcome rate of 79% to 85% at 2-year follow-up. As the use of the operating microscope became increasingly common among spinal surgeons, unilateral microscopic hemilaminotomy was developed as a means of sparing the contralateral musculature as well. This procedure was characterized by unilateral multifidus retraction, ipsilateral decompression, and also contralateral microscopic decompression performed under the midline bony and ligamentous structures. For this microscopic laminotomy as described by McCulloch21 and Young and colleagues,22 an 80% to 95% improvement rate was reported over a 9-month follow-up period. Despite this progressive movement toward less extensive resection of the posterior bony elements, symptomatic outcomes have remained similar regardless of the aggressiveness of the surgical procedure utilized to treat LSS.23 Indeed, in one of the only studies correlating the degree of radiographic with clinical outcome, it was observed that the satisfaction of patients with the results of surgery (e.g., Oswestry score and walking capacity) was more important in surgical outcome than the degree of decompression as seen on a postoperative CT scan.5

In the past decade, significant strides in microendoscopic visualization technology have been made. Accordingly, endoscopic-assisted procedures have become increasingly popular for the treatment of a wide range of spinal pathologies, including hyperhydrosis, herniated discs, tumors, and fractures. In the lumbar spine, microendoscopic-assisted discectomies (MEDs) have been used in treating herniated discs successfully for the last 5 years. The MED procedure has been particularly attractive for its small skin incision, gentle tissue dissection, excellent visualization, and ability to achieve results equivalent to those with open techniques. The microendoscopic decompressive laminotomy (MEDL) technique was thus developed as a synthesis of the unilateral hemilaminotomy, described earlier, and these MED techniques. The MEDL technique was initially validated in a series of cadaveric studies in which the equivalent bony decompressions were achieved via either an open or an endoscopic technique.24 Since then, it has also been studied clinically with resultant good surgical outcomes, low morbidity, and a rapid postoperative functional recovery.1 A bilateral decompression via a unilateral minimally invasive approach thus represents the next logical step in the evolution of modern surgical treatment for LSS.

Indications for Miss Decompressive Techniques

Patients with evidence of LSS in addition to spondylolisthesis, deformity, or severe degenerative disc disease may benefit from a minimally invasive transforaminal interbody fusion and percutaneous posterolateral instrumentation.19 Patients with severe spondylolisthesis or severe deformity, infection, tumor, arachnoiditis, pseudomeningocele, or cerebrospinal fluid fistula are generally not suitable candidate for MEDL. A thorough clinical and radiographic evaluation with use of dynamic flexion, extension, and lateral-bending radiographs, contrast-enhanced MRI and CT, and isotope scans should be performed to exclude these conditions. Prior surgery at the same level as the present stenotic area is also a relative contraindication. For these cases, significant epidural scarring and dense adhesions can make the MEDL technique particularly difficult with an increased risk of durotomy. However, in cases with a limited amount of decompression, a relatively intact facet complex, and little epidural scarring as shown on gadolinium-enhanced MRI, the MEDL procedure can be used to successfully achieve a repeat decompression. Redo procedures should be attempted only by surgeons who have already gained facility with the MEDL technique in a good number of simple cases. Additionally, patients undergoing redo decompression with MEDL should be clearly informed about the increased surgical risks and the possibility of conversion to an open procedure.

Surgical Technique

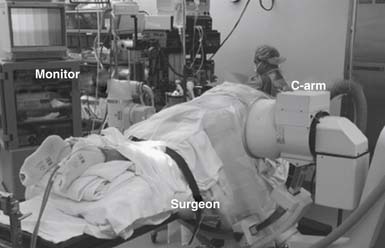

The patient is then turned into a prone position onto a radiolucent Wilson frame and Jackson table. Utmost care should be made to insure adequate padding of all pressure points, eyes, and extremities. The fluoroscopic C-arm should then be brought into the surgical field so that real-time lateral fluoroscopic images can be obtained. Ideally, this should be draped and positioned such that it can be easily swung in and out during the procedure without having to interrupt the flow of the case. The operative surgeon generally stands on the side of the approach with the C-arm and video monitors placed opposite him. However, the ultimate arrangement of the video monitor and C-arm monitor can be varied to allow for optimal ergonomic movements during the operation (Figure 59-1). Electromyographic (EMG) monitoring of motor nerve root responses can be used if desired.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree