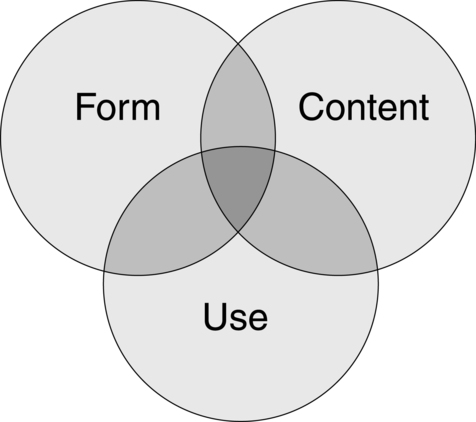

Chapter 1 Readers of this chapter will be able to do the following: 1. Give a brief history of the field of developmental language disorders. 2. Discuss terminology to describe children’s language-learning problems. 3. List the aspects and modalities of communication. 4. Discuss diagnostic issues that surround developmental language disorders. 5. Describe different methods used to investigate the biological bases of developmental language disorders. 6. Discuss comorbidity in developmental language disorders. 7. Summarize current theoretical models of developmental language disorders. The complexities surrounding DLD are illustrated by Jamie’s story. Descriptions of a syndrome of disorders of language learning in children date back to the early nineteenth century to the late eighteenth century (see de Montfort Supple, 2010; Stark, 2010 for more comprehensive reviews). Gall (1825) was one of the first to describe children with poor understanding and use of speech and to differentiate them from those with intellectual disability (ID). Subsequently, a great many discoveries about the relations between the brain and language behavior in adults were made by neurologists such as Broca (1861) and Wernicke (1874). The disorders Gall first identified were thought to be parallel to the aphasias these neurologists were studying in adults. For the first century of the existence of the study of language learning and its disorders, neurologists dominated the field, focusing attention on the physiological substrate of language behavior. The neurologist Samuel T. Orton (1937) can perhaps be thought of as the father of the modern practice of child language disorders. He emphasized the importance not only of neurological but also of behavioral descriptions of the syndrome and pointed out the connections between disorders of language learning and difficulties in the acquisition of reading and writing. In the 1940s and 1950s, other medical professionals, such as psychiatrists and pediatricians, took an interest in children who seemed to be unable to learn language but did not have mental retardation or deafness. Gesell and Amatruda (1947) were pioneers in developmental pediatrics; they devised innovative techniques for evaluating language development and recognized the condition they called “infantile aphasia.” Benton (1959, 1964) provided the fullest descriptions of children with this syndrome and is credited with evolving the concept of a specific disorder of language learning that is structured by excluding other syndromes, such as autism, deafness, and intellectual disorders, rather than by parallels to adult aphasia. At about the same time as these medical practitioners were refining notions of language disorders, another group of workers also was advancing concepts about children who failed to learn language. Ewing (1930); McGinnis, Kleffner, and Goldstein (1956); and Myklebust (1954, 1971) were all educators of the deaf and, as such, had developed a variety of techniques for teaching language to children who did not talk or hear. They all noticed that some deaf children’s language skills were worse than could be expected on the basis of their hearing impairment alone. This observation led them to focus more interest on the language impairment itself and to attempt to develop more effective methods of remediation for children who did not succeed with the standard approaches that were used to teach language to other children with hearing impairments. However, until the 1950s, no unified field of endeavor addressed the problems of the language-learning child; considered these problems to be disorders of language itself, rather than a result of some other syndrome (deafness, for example); or treated language disorder in children regardless of its cause. Aram and Nation (1982) give credit to three individuals for developing this new field: Mildred A. McGinnis, Helmer R. Myklebust, and Muriel E. Morley. These pioneers integrated the information currently available on language disorders in deaf and “aphasic” children and devised educational approaches that could be used to remediate the language dysfunctions demonstrated by these children. McGinnis (1963) developed the “association method” for teaching language to “aphasic” children. This method was very influential in the development of the field of language disorders, providing the first highly structured, comprehensive approach to language intervention. McGinnis also was one of the first to distinguish between two types of language problems seen in children: what she called expressive, or motor, aphasia (what we today would call expressive language disorder) and receptive, or sensory, aphasia (what we would term receptive language disorder). Morley (1957) was instrumental in applying information on normal language development to the problem of treating children with a language disorder and was one of the first individuals from a speech pathology background to push language and its disorders into the purview of the “speech therapist.” She fostered the use of detailed descriptions of children’s language behavior in making diagnoses and planning intervention programs. She also was important in providing definitions that allowed clinicians to distinguish language disorders from articulation disorders. Myklebust (1954) went, perhaps, the furthest in establishing a new and distinct field of study and practice, which he dubbed “language pathology.” Like Morley and McGinnis, he was interested in differential diagnosis. He developed schemes for classifying language disorders in children, which he called “auditory disorders,” and for differentiating them from deafness and ID. But Myklebust, like Orton, was also concerned with the continuities between disorders of oral language acquisition and their consequences for the acquisition of literacy skills. In founding the new discipline of language pathology, Myklebust pointed the way toward considering language disorders in this broad context, including difficulties not only in producing and comprehending oral language but also in the use of written forms of language. At about the same time that the field of language pathology was being established, the study of language itself was being revolutionized by the introduction of Chomsky’s (1957) theory of transformational grammar. This innovation led to an explosion in research on child language acquisition that the new discipline could use. In the 1960s and 1970s, as child language research expanded in focus from syntax to semantics to pragmatics and phonology, language pathology followed in its footsteps, broadening our view of the relevant aspects of language that needed to be described and addressed in clinical practice. The vast amount of new information on normal development being compiled made it possible for language pathologists to describe a child’s language behavior in great detail and to make specific comparisons to normal development on a variety of forms and functions. Furthermore, the large database on normal acquisition provided a blueprint of the language development process that could serve as a curriculum guide for planning intervention. This possibility has greatly influenced how language pathology is conceptualized and practiced today. Stark (2010) provides a history of language pathology from this period to the beginning of the current century. As the twentieth century drew to a close, rapid developments in our understanding of genetics and our ability to study brain structure and function greatly enriched the field of language pathology. It has become increasingly clear from family and twin studies that genetic factors exert a strong influence on language development and disorders (Bishop, 2009). However, it is equally clear that we are unlikely to discover a “gene for language” (Box 1-1). Instead, it is probable that multiple genes of small effect alter the way the brain develops in subtle but important ways, rendering the developmental path from genes to brain to behavior extremely complex and difficult to predict (Fisher, 2006). In addition, we now know that children with language impairments in the absence of other syndromes do not have obvious neurological lesions that could explain their language difficulty. In fact, we now know that children with early focal brain lesions rarely have long term deficits in language learning (Bates, 2004). This realization has led to some changes in the terminology we use to label language difficulties in children. Very often, speech, language, and communication impairments occur in the context of another developmental disorder with a recognized label, for example, ASD or Down syndrome (see Chapter 4). In these cases, descriptive terms such as speech, language, and communication impairment are very helpful in identifying the strengths and weaknesses of a child’s communication profile. However, when impairments are not associated with a more pervasive disorder, we seem to struggle to label them in a way that conveys a child’s needs or that the wider public readily recognizes and understands. This issue was highlighted by Kahmi (2004) who wondered why, unlike autism and dyslexia, “no one other than speech-language pathologists and related professionals seems to know what a language disorder is” (p. 105). One possible reason for this is that there are a variety of names given to the problems we have been discussing, including specific language impairment, language delay, language disability, language disorder, or developmental language disorder. In addition, the terms we use have changed considerably over time, while other diagnostic terms (such as dyslexia) have remained relatively stable. For instance, the term congenital aphasia (from the Greek word aphatos, meaning “speechless”) was first used in 1866 (de Monfort Supple, 2010), gradually becoming “developmental aphasia” or “dysphasia,” terms popular until the mid-twentieth century. These terms had their foundations in adult neuropsychology and referred specifically to loss of language ability following brain damage; when it became clear that developmental language disorders did not arise from similar neurological insults, these terms became less fashionable. The notion that language could be impaired in the context of “spared” capacities in other aspects of development led to labels such as specific language impairment (SLI) replacing dysphasia, at least in the research literature. But that is a mouthful and still suggests that deficits are restricted to speech, language, and communication. That is clearly not always (and indeed, many would argue, rarely) the case. In clinical practice, it is not uncommon to find practitioners describing language difficulties or delays, particularly with young children. This stems from a recognition that some children are “late bloomers” as far as language development is concerned; they generally catch up after a late start in learning to talk, and we can’t assume an underlying pathology in such cases. Still, a large body of research suggests that even late talkers who seem to catch up with peers often continue to show subtle weaknesses in language function (Rescorla, 2009). For all these reasons, we will use a term in this book that we believe is more neutral and descriptive than the others we have mentioned. We use the term developmental language disorder to describe children who are not acquiring language as would be expected for their chronological age, for whatever reason. 1. Children with primary DLD, for whom language impairments are the most salient presenting challenge, for whom the biological cause of disorder is not yet known, and for whom no other diagnostic label is appropriate. The most recent version of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of the American Psychiatric Association (DSM-V; APA, 2012) uses the term language impaired to refer to this group. 2. Children of school age with primary DLDs that co-exist with literacy disorders (dyslexia and poor reading comprehension), whom we will refer to as having language-learning disorders to call attention to the consequences of their difficulties on academic achievement. We will focus on these children in Section III of this book. 3. Children with DLDs that are associated with or secondary to some other developmental disorder such as ASD or intellectual impairment (ID). We will discuss many of the syndromes that are often accompanied by DLD in Chapter 4. Bloom and Lahey (1978) and Lahey (1988) provided a useful framework for exploring language competencies that has stood the test of time. They suggested that language is comprised of three major aspects, illustrated in Figure 1-1: 1. Form: including syntax, morphology, and phonology 2. Content: essentially consisting of semantic components of language, vocabulary knowledge, and knowledge of objects and events 3. Use: the realm of pragmatics, or the ability to use language in context for social purposes. Below is an outline of the key linguistic characteristics of DLD with respect to form, content, and use (summarized in Table 1-1). Not all of these features will be present in all children with a diagnosis of DLD and the features that characterize a child at one age may be very different to the features that stand out as that child gets older. Let’s look at these features in a little more detail. Table 1-1 Common Linguistic Characteristics of Primary DLD Deficits in grammar are hallmarks of primary DLD. While many grammatical deficits occur in the context of weak phonology and semantics, it may also be possible for grammatical deficits to occur in isolation (van der Lely, 2005). The most consistently reported finding is that young children with primary DLD omit morphosyntactic markers of grammatical tense in spontaneous speech where these morphemes are obligatory. These errors include omission of past tense –ed (“He walk__ to school yesterday”), third person singular –s (“She walk__ to school everyday”), and the copular form of the verb be (“I eating chocolate”) (Rice, Wexler, & Cleave, 1995). An important observation is that these are errors of omission, not commission (Bishop, 1994); in other words children do not confuse tenses and morphemes. These grammatical forms are typically acquired by the age of 5, therefore persistent errors in older children is a sensitive indicator of language impairment. Older children with DLD have problems producing wh- questions (van der Lely & Battell, 2003), may omit obligatory verb arguments (“the woman is placing on the saucepan”), and use fewer verb alternations (“the girl is opening the door” versus “the door is opening”) (Thoradottir & Weismer, 2002). These deficits in production are matched by problems in making grammaticality judgments (Rice, Hoffman, & Wexler, 2009) and in understanding complex syntax. For instance, children with DLD have poor understanding of passive constructions (“the boy was kissed by the girl”), embedded clauses (“the boy chasing the horse is fat”), pronominal reference (e.g., knowing who “him” refers to in the sentence “Mickey Mouse says Donald Duck is tickling him”), locatives (“the apple is on the napkin”) and datives (“give the pig the goat”) (Bishop, 1979; van der Lely & Harris, 1990). Although grammatical errors are a striking feature of DLD, it is not the case that children with DLD completely lack grammatical knowledge. Instead, children are inconsistent in their application of this knowledge, behaving as if certain grammatical rules were “optional” (Bishop, 1994; Rice et al., 1995). If children lacked knowledge, on formal tests of grammatical understanding we would expect either a systematic response bias (i.e., always interpreting a passive sentence such as “the boy was kissed by the girl” by word order “boy kiss girl”) or random guessing. In fact, performance on grammatical tests is typically above chance levels, even when non-syntactic strategies to support understanding are not evident. This suggests that factors other than grammatical knowledge influence performance, a hypothesis supported by the finding that grammatical errors may be induced in typically developing individuals by increasing processing demands (Hayiou-Thomas, Bishop, & Plunkett, 2004). Phonological deficits are frequently described in terms of a child’s repertoire of available speech sounds and the consistent error patterns a child uses in speech. An epidemiological study of 6-year-olds in the United States found the prevalence of speech sound disorders (SSD) to be 3.8% with a co-occurrence of SSD and language impairments of 1.3% (Shriberg, Tomblin, & McSweeny, 1999). Problems with speech production are likely to be more prevalent in clinically referred samples, perhaps because they are more readily identified by parents and teachers (Bishop & Hayiou-Thomas, 2008). Children with DLD tend to have impoverished vocabularies throughout development (Beitchman et al., 2008), but their semantic difficulties extend beyond the number of words available to them. In general, children with DLD are slow to learn new words, have difficulty retaining new word labels, encode fewer semantic features of newly learned items, and require more exposure to novel words in order to learn them (Alt, Plante, & Creusere, 2004). Children with DLD often make naming errors for words they do know, for instance, labelling “scissors” as “knife” or using less specific language such as “cutting things.” As children get older, the problem may not be how many words the child knows, but what the child knows about those words. For instance, children with DLD may not realize that words can have more than one meaning, for example that “cold” can refer to the temperature outside, an illness, or a personal quality of unfriendliness. This lack of flexible word knowledge may account for reported difficulties in understanding jokes, figurative language, and metaphorical language, all of which draw on in-depth knowledge of semantic properties of words, and how words relate to one another (Norbury, 2004). Finally, there is some indication that learning about verbs may be a particular source of difficulty for children with DLD (Riches, Tomasello, & Conti-Ramsden, 2005). Problems acquiring verbs may have implications for learning about sentence structure because of the unique role verbs have in determining other sentence constituents (arguments) and in signalling grammatical tense. Pragmatics is commonly associated with the notion of “social communication,” which encompasses formal pragmatic rules, social inferencing, and social interaction (Adams, 2008). In general, pragmatic skills of children with primary DLD are considered to be immature rather than qualitatively abnormal, as in the case of autism. In addition, although they perform more poorly than age-matched peers on various measures of social understanding, their difficulties are rarely as severe as those seen in autism. Nevertheless, children with DLD may have difficulties understanding and applying pragmatic rules. In conversation these may include initiating and maintaining conversational topics, requesting and providing clarification, turn-taking, and matching communication style to the social context. Children with DLD may be impaired relative to peers in their understanding of other minds (Farrar et al., 2009) and in understanding emotion from a situational context (Spackman, Fujiki, & Brinton, 2006). Individuals with DLD also have difficulties integrating language and context, resulting in difficulties generating inferences about implicit information in discourse (Adams, Clarke, & Haynes, 2009), understanding figurative language (Norbury, 2004) and constructing coherent narratives (Reed, Patchell, Coggins, & Hand, 2007). Chapman (1992), Miller (1981), and Miller and Paul (1995) talked about language in terms of its two primary modalities—comprehension and production—integrating each of the three aspects previously listed within these two modalities. From their viewpoint, language disorders would be defined according to the modalities primarily affected; the aspects or domains affected within these modalities are used to describe the language disorder once it is identified. But whether it is the domains and their interactions or the modalities of language that are used to define disorders, the important point is that disorders be defined broadly. We certainly want to be able to identify clients who fit the traditional idea of a child with a DLD (the one who has trouble learning to put words together to make sentences), but we also want to be able to identify and, therefore, help the child like Tommy, who is described in the following text. Tommy might be considered a child with high-functioning ASD syndrome (see Chapter 4), but the primary manifestation of his disorder is in social communication, not in the understanding or production of sounds, words, or sentences. It is important that a definition of language disorder allow a child such as Tommy to qualify for services, even though his problem is confined to the use of language for communicative purposes, with formal aspects of language relatively unaffected. Why might we want to use mental age, rather than chronological age, as a reference point to decide whether a child has a language disorder? For one thing, we usually would not expect a child’s language skills to be better than the general level of development. Should a child functioning at a 3-year-old level overall be expected to achieve language skills commensurate with his chronological age of 8 years? Miller (1981) suggests that language level very rarely exceeds nonverbal cognitive level in the developmentally delayed population, even though the relationships between language and cognition are more complex and variable in normal development (Krassowski & Plante, 1997; Miller, Chapman, Branston, & Reichle, 1980; Notari, Cole, & Mills, 1992; Rice, Warren, & Betz, 2005). But criteria for disability that are based on discrepancies between scores on IQ and other tests are no longer thought to be valid. Lahey (1990) was perhaps the first in the field of language pathology to stake out a position against mental-age referencing. She pointed out that many psychometric problems are associated with measuring mental age. For one, it is not psychometrically acceptable to compare age scores derived from different tests of language and cognition that were not constructed to be comparable, were not standardized on the same populations, and may not have similar standard errors of measurement or ranges of variability (see Chapter 2). Second, there are fundamental problems in using age-equivalent scores at all to determine whether a child’s score falls outside the normal range. These issues are discussed further in Chapter 2. Lahey also emphasized the theoretical difficulties of assessing nonverbal cognition, centering her argument on the justification for deciding which of the many possible aspects of nonlinguistic cognition ought to be the standard of comparison. For all of these reasons, Lahey suggested that chronological age is the most reliably measured benchmark against which to reference language skill to identify language disorders. Remember Jamie? The two clinicians involved in his case differed on precisely this point. But ASHA (2000a) argued strongly against “cognitive-referencing” in making decisions about eligibility for services. A major criticism is that different combinations of tests can yield different eligibility recommendations for the same student. How can this be? Often, young children with DLD show an uneven language profile, with severe deficits in morphology and syntax and relative strengths in vocabulary knowledge (Abbeduto & Boudreau, 2004; Rice, 2000, 2004). Therefore, we might expect vocabulary scores to be more in line with nonverbal IQ scores, while tests of morphosyntax might result in a very large discrepancy. A second criticism is that longitudinal studies of children with language disorders have reported a drop in nonverbal IQ scores over time (Botting, 2005; Stothard, Snowling, Bishop, Chipchase, & Kaplan, 1998). It is unlikely that this reflects an actual loss in ability; rather it shows that nonverbal assessments are rarely “pure” measures of nonverbal ability. The majority of nonverbal tests incorporate verbal directions, and many linguistically able children use verbal strategies to help them reason out the answers. This puts the child with DLD at a distinct disadvantage. Third, the degree of discrepancy between verbal and nonverbal abilities does not necessarily predict a child’s responsiveness to intervention. Research has shown that children with generally depressed nonverbal scores can still benefit from therapy (Fey, Long, & Cleave, 1994). Finally, a categorical denial of services to children because of generally depressed nonverbal IQ scores is not consistent with the ethos of the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA Amendments of 1997, Public Law 105-17), which stipulates that services be determined on an individual basis (Whitmire, 2000a). Clearly there are many different ways that language may be impaired, which raises the question of whether there are subtypes of DLD. For example, van der Lely (2005) describes children with “grammatical-SLI,” in which grammatical skills are more severely impaired relative to other aspects of the language system. In addition, there has been considerable debate in the literature regarding the diagnostic status of children with “pragmatic language impairments,” or PLI, and whether they are continuous with more specific language impairments or autism (cf. Whitehouse, Watt, Line, & Bishop, 2009). Nosologies for “subtypes” of language disorder have been used for a number of years (cf. Conti-Ramsden et al., 1999; Rapin and Allen, 1987), but are they useful constructs? One assumption here is that the biological mechanisms that give rise to a particular subgroup, “G-SLI” for example, differ from those that give rise to other types of language difficulty. At the moment there is simply insufficient evidence that this is the case. A second concern is that these nosologies rarely take development into account. Longitudinal studies have demonstrated that although subgroups appear to exist throughout the school years, the children that make up those subgroups move fluidly between them over time (Conti-Ramsden et al., 1999; Tomblin et al., 2003). In other words, children may start off with a predominantly lexical-syntactic pattern of language disorder, but, as they grow older, may more closely resemble children with pragmatic language concerns. Information about very young children who go on to have “G-SLI” is lacking; we therefore don’t know if these children are characterized by more pervasive language, perceptual, or cognitive deficits at earlier developmental time points. In other words, while the presence of a language disorder tends to be stable over time, the nature of that language disorder is very likely to change.

Models of child language disorders

A brief history of the field of language pathology

Terminology

Speech, language and communication

What’s in a name?

Aspects and modalities of language disorder

Form

Errors in speech production and poor phonological awareness; i.e., the ability to manipulate sounds of the language, particularly in the preschool years.

Errors in marking grammatical tense, specifically the omission of past-tense –ed and third person singular –s, as well as omission of copular “is,” and errors in case assignment (e.g., “Him run to school yesterday”).

Simplified grammatical structures and errors in complex grammar, for example, poor understanding/use of passive constructions (“the boy was kissed by the girl”), wh- questions, dative constructions (“the boy is giving the girl the present”)

Content

Delayed acquisition of first words and phrases

Restricted vocabulary and/or problems finding the right word for known objects, for example uses the word “thing” for most common objects

Use

Difficulties understanding complex language and long stretches of discourse

Difficulties telling a coherent narrative

Difficulties understanding abstract and ambiguous language

Form

Content

Use

Diagnostic issues

DLD relative to what?

Are there subtypes of DLD?

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Neupsy Key

Fastest Neupsy Insight Engine

When 6-year-old Jamie was referred for assessment in September, the school’s speech-language pathologist (SLP), Ms. Reese, conducted an intensive assessment and reported that Jamie was functioning at the level of a 4-year-old in terms of his expressive and receptive language abilities. The school psychologist also tested Jamie and reported that his nonverbal skills (as measured by a standard IQ test) were borderline, not low enough to be identified as globally delayed or to warrant placement in a special classroom. Ms. Reese therefore decided to include Jamie in her caseload because her testing clearly indicated that his language skills were below the level expected for his chronological age.

When 6-year-old Jamie was referred for assessment in September, the school’s speech-language pathologist (SLP), Ms. Reese, conducted an intensive assessment and reported that Jamie was functioning at the level of a 4-year-old in terms of his expressive and receptive language abilities. The school psychologist also tested Jamie and reported that his nonverbal skills (as measured by a standard IQ test) were borderline, not low enough to be identified as globally delayed or to warrant placement in a special classroom. Ms. Reese therefore decided to include Jamie in her caseload because her testing clearly indicated that his language skills were below the level expected for his chronological age.

Tommy was a very easy baby. His mother remembers that he was happy to lie in his crib for hours on end, watching his mobile. By age 2 Tommy was using long, complicated sentences and knew the name of every model of vehicle on the road, as well as the names of most of the parts of their engines. At age 4 he took apart the family lawn mower and put it back together. However, his preschool teacher was concerned about him. He took almost no interest in the other children, choosing, when he spoke, to speak only to adults. When he did talk, he invariably asked complex but inappropriate questions on his few topics of interest, such as mechanical objects. He dwelled incessantly on a few events that were of great importance to him, such as the time the doors of the family car would not open. Tommy seemed very bright in many ways and did well on an IQ test that was part of his kindergarten screening. But in social settings, he just did not know how to relate, and his language was used primarily to talk about his own preoccupations rather than real interactions.

Tommy was a very easy baby. His mother remembers that he was happy to lie in his crib for hours on end, watching his mobile. By age 2 Tommy was using long, complicated sentences and knew the name of every model of vehicle on the road, as well as the names of most of the parts of their engines. At age 4 he took apart the family lawn mower and put it back together. However, his preschool teacher was concerned about him. He took almost no interest in the other children, choosing, when he spoke, to speak only to adults. When he did talk, he invariably asked complex but inappropriate questions on his few topics of interest, such as mechanical objects. He dwelled incessantly on a few events that were of great importance to him, such as the time the doors of the family car would not open. Tommy seemed very bright in many ways and did well on an IQ test that was part of his kindergarten screening. But in social settings, he just did not know how to relate, and his language was used primarily to talk about his own preoccupations rather than real interactions.