65 Mononeuropathies of the Upper Extremities

Mononeuropathies of the Shoulder Girdle

Dorsal Scapular Neuropathies

Clinical Vignette

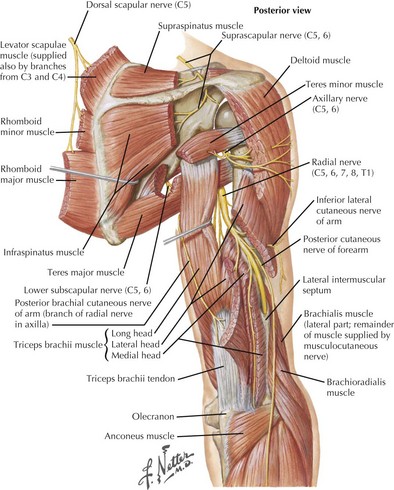

The dorsal scapular nerve receives fibers from the C5 nerve root. It innervates the levator scapulae and the rhomboideus major and minor muscles, which assist in stabilization of the scapula, rotation of the scapula in a medial–inferior direction, and elevation of the arm (Fig. 65-1). Rhomboid weakness can lead to scapular winging, which is most prominent when the patient raises the arm overhead. Possible etiologies of injury to this nerve include shoulder dislocation, weightlifting, and entrapment by the scalenus medius muscle.

Long Thoracic Neuropathies

Clinical Vignette

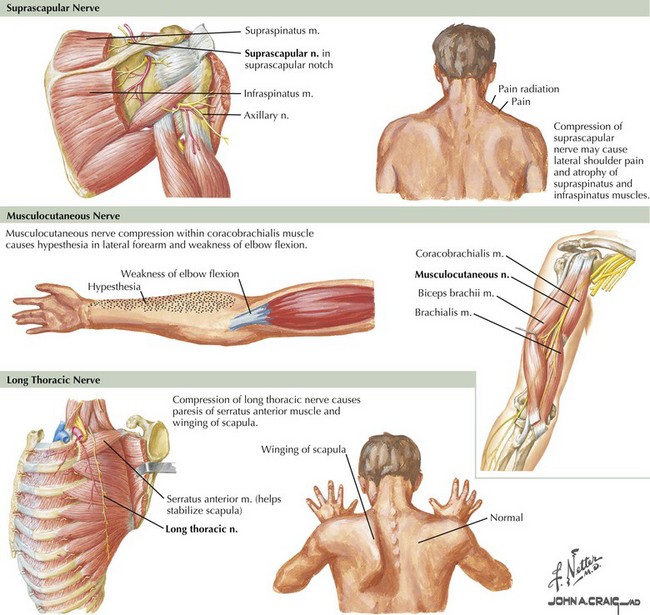

The long thoracic nerve originates directly from C5–C7 roots, before the formation of the brachial plexus. It innervates the serratus anterior muscle and has no cutaneous sensory representation (Fig. 65-2). Weakness of the serratus anterior is debilitating, because it stabilizes the scapula for pushing movements and elevates the arm above 90 degrees. This is the most common cause of scapular winging; it is best recognized by having the patient push against a wall. The inferior medial border is the most prominently projected away from the body wall. A dull shoulder ache may accompany this neuropathy. When severe acute pain occurs with the onset of scapular winging, brachial plexus neuritis should be considered.

Suprascapular Neuropathies

Clinical Vignette

The suprascapular nerve emerges from the upper trunk of the brachial plexus, receiving fibers from C5 and C6 roots. It does not have any cutaneous innervation. The suprascapular nerve first provides innervation to the supraspinatus muscle, a shoulder abductor, and then to the infraspinatus, a shoulder external rotator (see Fig. 65-1). The suprascapular nerve may be injured at the suprascapular notch, before the innervation of the supraspinatus muscle, or distally at the spinoglenoid notch, affecting the infraspinatus alone (see Fig. 65-2). The most common site of entrapment is at the suprascapular notch, under the transverse scapular ligament. Acute-onset cases result from blunt shoulder trauma, with or without scapular fracture, or from forceful anterior rotation of the scapula. The suprascapular nerve may also be affected by brachial plexus neuritis in isolation or with other nerves. Suprascapular neuropathies of insidious onset often occur subsequent to callous formation after fractures, from entrapment at the suprascapular or spinoglenoid notch, by compression from a ganglion or other soft tissue mass, or by traction caused by repetitive overhead activities such as volleyball or tennis.

Axillary Neuropathies

Clinical Vignette

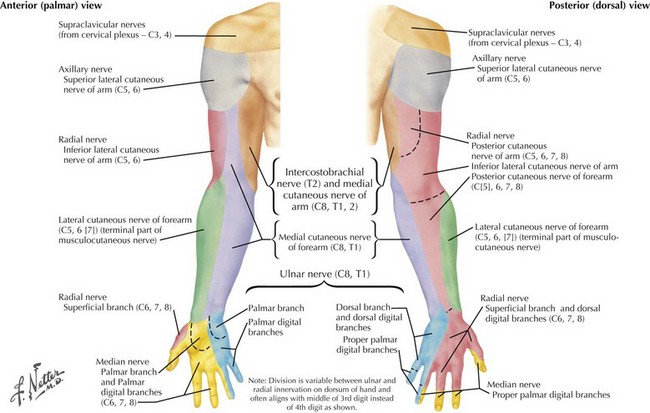

The axillary nerve, along with the radial nerve, is a terminal branch of the posterior cord of the brachial plexus. It innervates the deltoid and the teres minor and provides sensory innervation to the lateral upper part of the shoulder via the superior lateral brachial cutaneous nerve of the arm (Figs. 65-1 and 65-3). In lesions of the axillary nerve, shoulder abduction is weakened and cutaneous sensibility of the lateral shoulder diminishes, overlapping the C5 dermatome. Because the teres minor is not the predominant external rotator of the shoulder, clinical isolation and testing are difficult. EMG may be necessary to define neurogenic injury to this muscle. Most axillary neuropathies are traumatic, related to anterior shoulder dislocations, humerus fractures, or both. Recognition of nerve injury may be delayed because of the shoulder injury. Acute axillary neuropathies can result from blunt trauma or as a component or sole manifestation of brachial plexus neuritis.

Musculocutaneous Neuropathies

Clinical Vignette

The musculocutaneous nerve originates directly from the lateral cord of the brachial plexus. It innervates the coracobrachialis, biceps brachii, and brachialis muscles and terminates in its cutaneous branch, the lateral antebrachial cutaneous nerve. Isolated musculocutaneous neuropathies are rare. They have been reported in weight lifters, after surgery, and after prolonged pressure during sleep. Damage to the musculocutaneous nerve results in weakness of forearm flexion and supination and sensory loss of the lateral volar forearm (see Fig. 65-2). The biceps reflex is diminished, but the brachioradialis reflex (same myotome, different nerve) is preserved. More commonly, injury to this nerve occurs as part of a more widespread traumatic injury, usually involving the proximal humerus. The musculocutaneous nerve can also be preferentially involved in acute brachial plexus neuritis. Distal lesions of the lateral antebrachial cutaneous nerve may result from attempted cannulation of the basilic vein in the antecubital fossa. Rupture of the biceps tendon is a significant differential diagnostic consideration of musculocutaneous neuropathy.

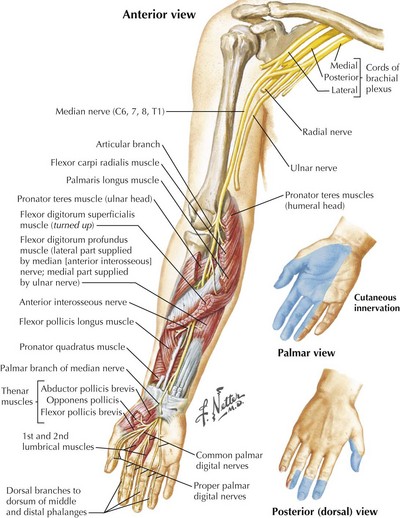

Median Mononeuropathies

The anatomy of the median nerve is important in understanding the signs and symptoms of entrapment lesions at the level of the wrist, versus the more proximal lesions. The median nerve provides essential motor and sensory function to the lateral aspect of the hand (Fig. 65-4). It supplies the intrinsic hand muscles of most of the thenar eminence and innervates several forearm muscles. Its major sensory role is to provide innervation for the thumb, index, and middle fingers and the lateral half of the ring finger.