7

MYOCLONUS

DESCRIPTION

Sudden, brief, shocklike, involuntary movements result from brief contractions (or lapse in contractions) of a muscle or group of muscles.1

Sudden, brief, shocklike, involuntary movements result from brief contractions (or lapse in contractions) of a muscle or group of muscles.1

When the movement results from a contraction of muscles, it is also termed positive myoclonus.

When the movement results from a contraction of muscles, it is also termed positive myoclonus.

The movement is called negative myoclonus when it results from a transient loss of muscle contraction.

The movement is called negative myoclonus when it results from a transient loss of muscle contraction.

Friedreich first described myoclonus as a separate entity in a case report in 1881, but it was in 1883 that Lowenfeld used the term myoclonus for the first time.

Friedreich first described myoclonus as a separate entity in a case report in 1881, but it was in 1883 that Lowenfeld used the term myoclonus for the first time.

In 1903, Lundborg proposed a classification scheme for myoclonus: symptomatic, essential, and familial.

In 1903, Lundborg proposed a classification scheme for myoclonus: symptomatic, essential, and familial.

Lindenmulder described the first family with essential myoclonus and drew attention to its occurrence in nondegenerative conditions without metabolic derangements or epilepsy.2

Lindenmulder described the first family with essential myoclonus and drew attention to its occurrence in nondegenerative conditions without metabolic derangements or epilepsy.2

PHENOMENOLOGY AND DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

Although myoclonus is quite distinctive in its presentation with “sudden shocklike movements,” it may sometimes still be confused with other movement disorders, such as tics, chorea, dystonia, and tremor. It then becomes important to make sure that the phenomenology is consistent with myoclonus (Table 7.1).

Although myoclonus is quite distinctive in its presentation with “sudden shocklike movements,” it may sometimes still be confused with other movement disorders, such as tics, chorea, dystonia, and tremor. It then becomes important to make sure that the phenomenology is consistent with myoclonus (Table 7.1).

CLINICAL APPROACH

There is no single best way to approach a patient with myoclonus.

There is no single best way to approach a patient with myoclonus.

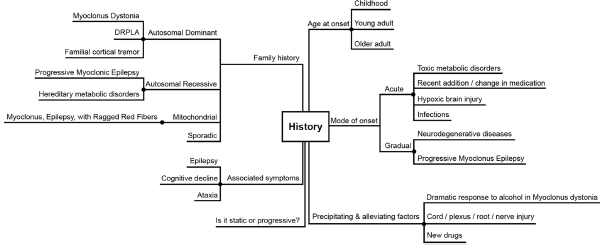

Here is a suggested sequence to follow (Figures 7.1–7.3).

Here is a suggested sequence to follow (Figures 7.1–7.3).

Table 7.1

Clinical Presentation of Myoclonus Compared With Other Hyperkinetic Movement Disorders

Tics | Myoclonus |

Do not interfere with motor acts | May interfere with motor acts |

Can be voluntarily suppressed | Cannot be suppressed |

Preceded by an internal urge and followed by relief | No urge or relief |

Often disappear during sleep | May continue in sleep |

Stereotyped and repetitive | May be random or localized |

Slower than myoclonus | Faster than tics |

Chorea | Myoclonus |

Not stimulus-sensitive | May be stimulus-sensitive |

Movements in constant flow, randomly distributed over body and in time | No sequential movement of body parts |

With motor impersistence (fly catcher tongue, milkmaid grip) | No motor impersistence |

Slow or impaired Luria three-step test | Normal Luria test (unless associated with encephalopathy/dementia) |

Dystonia | Myoclonus |

Prolonged muscle spasms with twisting and posturing | Sudden brief contraction of muscles that may move a joint |

May have sensory trick | No sensory trick |

Postural/action tremor | Myoclonus |

Rhythmic | May be rhythmic or arrhythmic |

Frequency usually slower | Usually faster |

Fasciculations | Myoclonus |

Usually do not move a joint | May or may not move a joint |

CLASSIFICATION

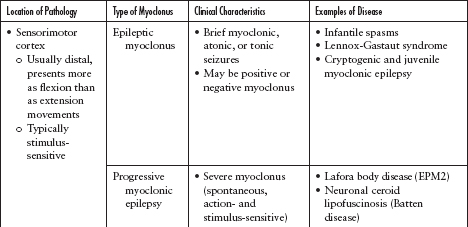

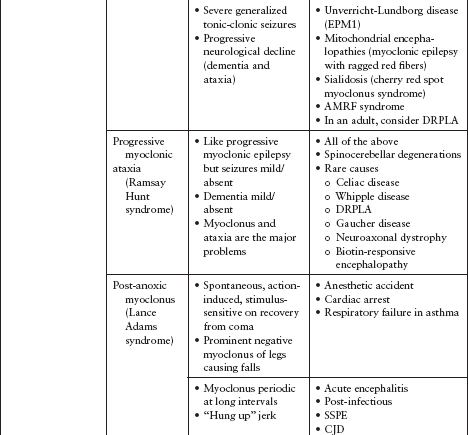

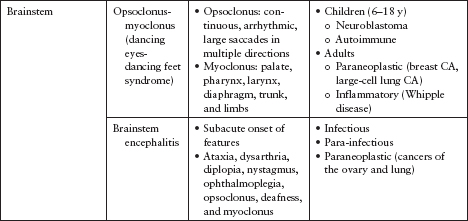

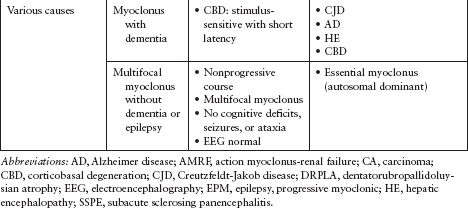

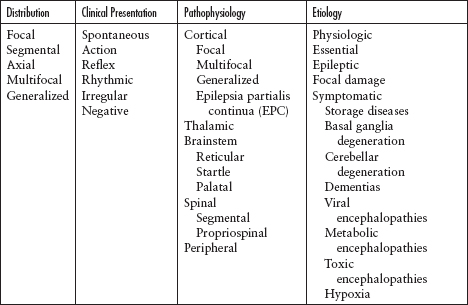

Myoclonus may be classified in several ways: according to distribution, clinical presentation, pathophysiology, or etiology (Table 7.2).

Myoclonus may be classified in several ways: according to distribution, clinical presentation, pathophysiology, or etiology (Table 7.2).

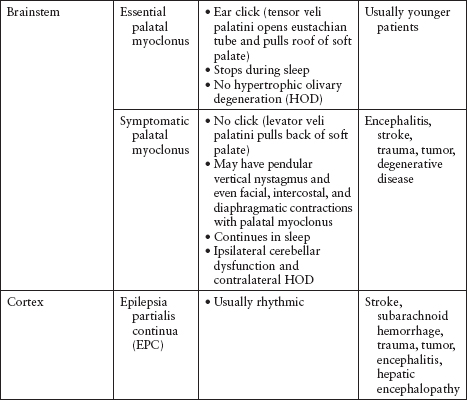

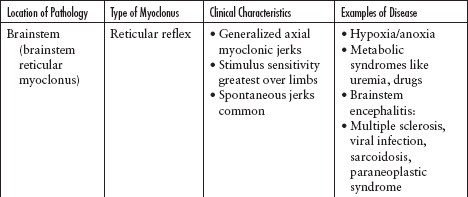

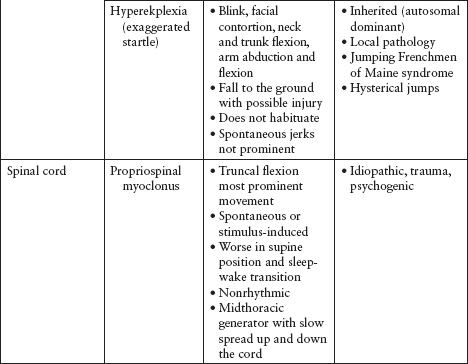

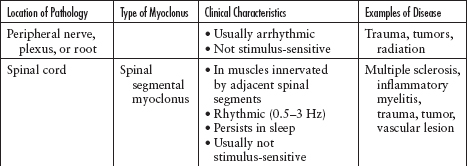

Identifying myoclonus by its distribution and/or type may assist in localizing the pathology (Table 7.3A, B).

Identifying myoclonus by its distribution and/or type may assist in localizing the pathology (Table 7.3A, B).

Figure 7.1

Suggested general approach to myoclonus.

After determining the distribution of myoclonus, look for clues to possible underlying pathology (Table 7.4A–C).

After determining the distribution of myoclonus, look for clues to possible underlying pathology (Table 7.4A–C).

SPECIFIC ETIOLOGIES OF MYOCLONUS

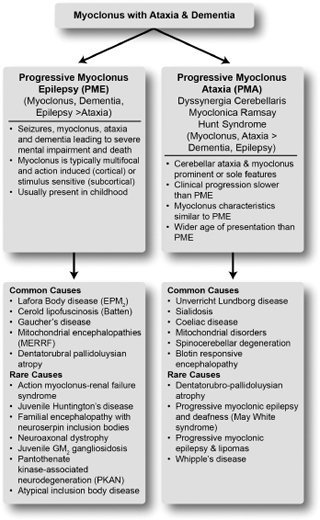

Myoclonus with ataxia and epilepsy

Myoclonus with ataxia and epilepsy

Drug-induced myoclonus

Drug-induced myoclonus

Myoclonus secondary to underlying conditions accounts for 72% of cases (Figure 7.4).3

Myoclonus secondary to underlying conditions accounts for 72% of cases (Figure 7.4).3

A detailed drug history with identification of all current and recent medications is imperative. Drug-induced myoclonus is especially common in hospitalized patients (Table 7.5).4

A detailed drug history with identification of all current and recent medications is imperative. Drug-induced myoclonus is especially common in hospitalized patients (Table 7.5).4

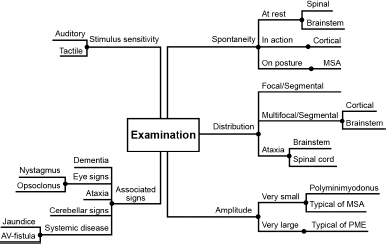

Figure 7.2

Specific questions to ask during the historical assessment of a patient with myoclonus.

Figure 7.3

Things to look for when examining a patient with myoclonus.

Table 7.2

Methods of Classifying Myoclonus

Distribution | Description | Location of Pathology |

Focal/Segmental | Confined to a particular region of the body | Peripheral nerve, root, plexus, spinal cord, brainstem, or cortex |

Axial | Flexion of neck, trunk, and hips; abduction of arms | Brainstem or spinal cord |

Multifocal | Different parts of the body, not necessarily at the same time | Sensory motor cortex or brainstem |

Generalized | Whole body affected in a single jerk | Sensory motor cortex or brainstem |

Table 7.3B

Clinical Characteristics of Myoclonus and Their Importance

Type of Myoclonus | Clinical Description | Examples |

Spontaneous | • May be unpredictable or occur at specific times • May be focal, multifocal, or generalized | • Early morning myoclonus in juvenile myoclonic epilepsy • Hypnic jerks when falling asleep • Palatal myoclonus • Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease |

Action | • During active muscle contraction, posture, and movement • Is the most debilitating myoclonus, interferes with gross voluntary movements • May be multifocal or generalized > focal/segmental | • Lance Adams syndrome (posthypoxic myoclonus) |

Reflex | • May be focal or generalized, proximal > distal muscles and flexors > active than extensors • May look like a tremor • Stimulus may be somesthetic, visual, or auditory • Somesthetic: tap the face (mentalis zone) for generalized reflex myoclonus, tendon reflex • Auditory: common in children, usually provoked by unexpected sounds; differentiate from hyperekplexia • May be very sensitive, self-perpetuate, and simulate spontaneous myoclonus | • Brainstem reflex reticular myoclonus |

Rhythmic | • Focal or segmental • Always spontaneous • Usually slow (1–4 Hz) • Persists in sleep (ask bed partner) • Usually due to focal lesion of spinal cord or brainstem | • Spinal myoclonus • Palatal myoclonus |

Negative | • Always during action/posture • Sudden, transient loss of muscle tone in an actively contracting muscle | • Asterixis in hepatic encephalopathy • “Bouncy legs” in Lance Adams syndrome causing falls |

Table 7.4A

Possible Etiologies of Focal Myoclonus

Inherited disorders presenting with myoclonus (Table 7.6A–C)5

Inherited disorders presenting with myoclonus (Table 7.6A–C)5

Essential myoclonus

Essential myoclonus

Essential myoclonus can be hereditary or sporadic (Figure 7.5).

Essential myoclonus can be hereditary or sporadic (Figure 7.5).

Opsoclonus-myoclonus-ataxia syndrome (Table 7.7)3,6–11

Opsoclonus-myoclonus-ataxia syndrome (Table 7.7)3,6–11

Palatal myoclonus (Figure 7.6)

Palatal myoclonus (Figure 7.6)

Myoclonus in neurodegenerative extrapyramidal disorders (Figure 7.7)

Myoclonus in neurodegenerative extrapyramidal disorders (Figure 7.7)

Physiologic myoclonus

Physiologic myoclonus

This occurs as the body’s physiologic response to certain external or internal triggers in otherwise healthy individuals and includes hiccups (singultus), hypnic jerks that are abundant in the facial and distal limb muscles, and physiologic startle.

This occurs as the body’s physiologic response to certain external or internal triggers in otherwise healthy individuals and includes hiccups (singultus), hypnic jerks that are abundant in the facial and distal limb muscles, and physiologic startle.

These symptoms do not usually need to be treated.

These symptoms do not usually need to be treated.

Orthostatic myoclonus (OM)

Orthostatic myoclonus (OM)

A relatively recent observation of myoclonus that occurs on standing12,13 and in subjects who may or may not have neurodegenerative conditions like Parkinson’s disease (PD). It may be even more common than orthostatic tremor.14

A relatively recent observation of myoclonus that occurs on standing12,13 and in subjects who may or may not have neurodegenerative conditions like Parkinson’s disease (PD). It may be even more common than orthostatic tremor.14

The most frequent symptom was unexplained unsteadiness in a series of patients referred for gait imbalance and tested. OM was diagnosed in 17.2% of the patients.14

The most frequent symptom was unexplained unsteadiness in a series of patients referred for gait imbalance and tested. OM was diagnosed in 17.2% of the patients.14

The most frequent comorbid neurological condition was parkinsonism.14

The most frequent comorbid neurological condition was parkinsonism.14

Figure 7.4

Classification of secondary myoclonus associated with epilepsy, dementia, and ataxia.

Asterixis (negative myoclonus)

Asterixis (negative myoclonus)

First described in 1949 by Adams and Foley in hepatic encephalopathy as rhythmic movements of the fingers and occasionally of the arms, legs, and face at 3 to 5 Hz on active maintenance of posture.15 The term asterixis was coined by the same investigators in 1953 when they identified that this movement follows pauses of 200 to 500 msec.16 The term negative myoclonus was coined by Shahani and Young in 1976.17

First described in 1949 by Adams and Foley in hepatic encephalopathy as rhythmic movements of the fingers and occasionally of the arms, legs, and face at 3 to 5 Hz on active maintenance of posture.15 The term asterixis was coined by the same investigators in 1953 when they identified that this movement follows pauses of 200 to 500 msec.16 The term negative myoclonus was coined by Shahani and Young in 1976.17

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree