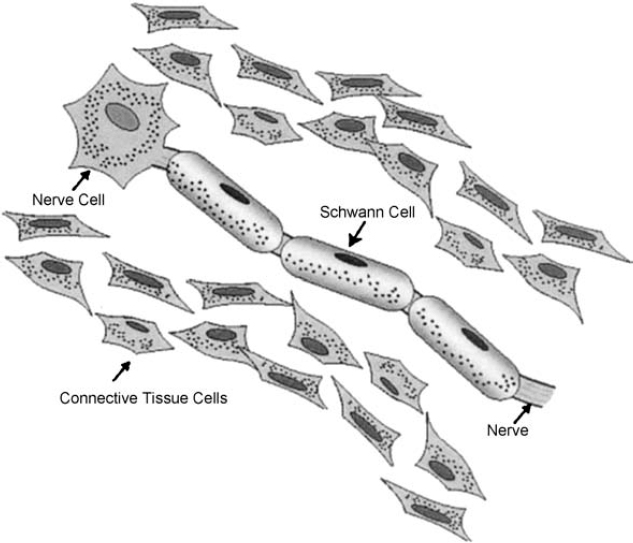

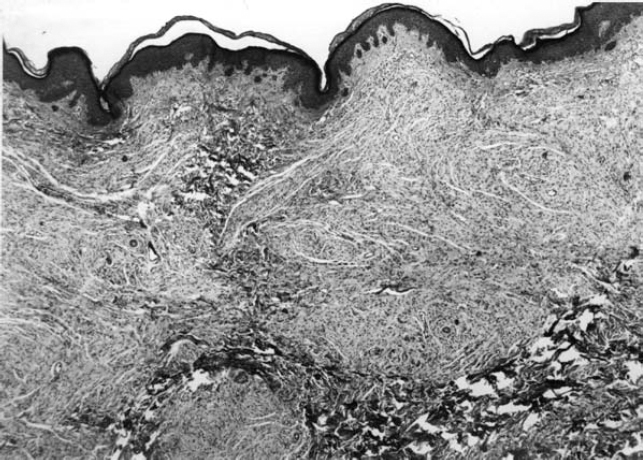

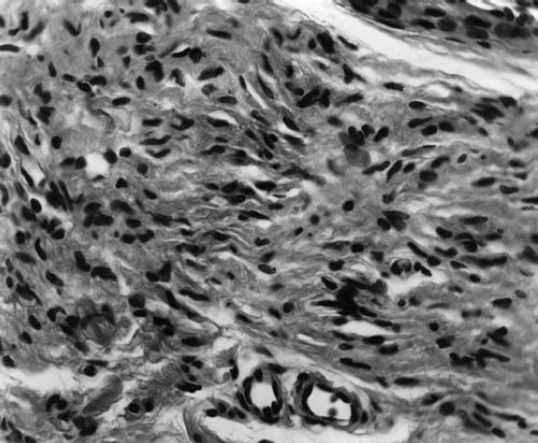

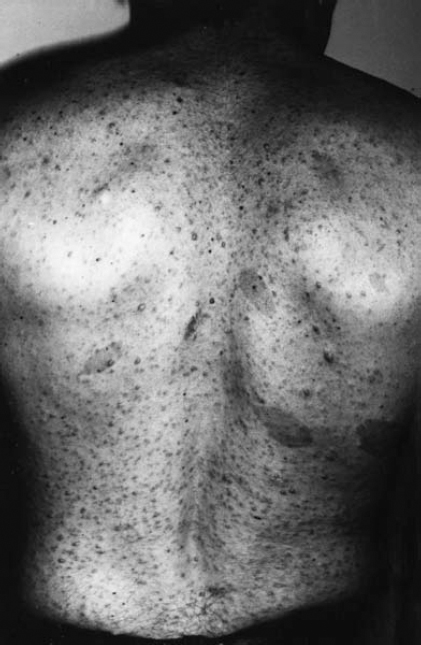

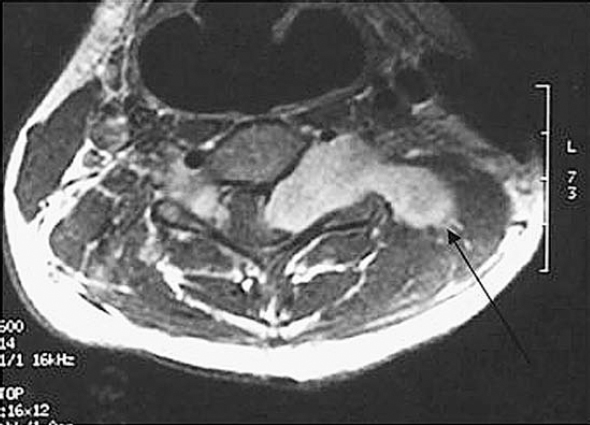

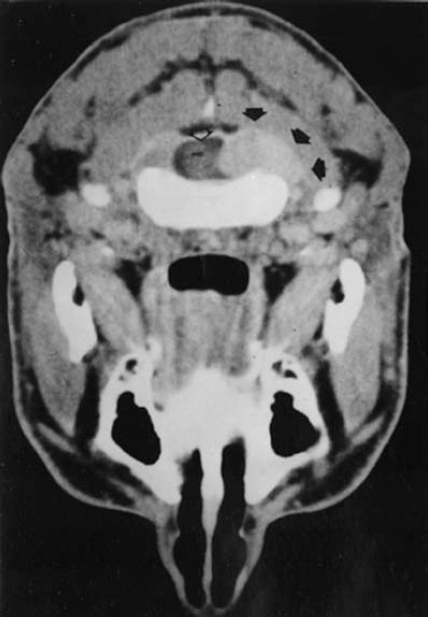

6 The growth of multiple neurofibromas is not only the hallmark feature of neurofibromatosis 1 (NF1), but also is one of its most complex manifestations. In the century since von Recklinghausen first observed that neurofibromas develop from the myelin sheath of tissue surrounding nerves, researchers have learned much more about how these tumors develop and grow (see Chapter 3). Yet much remains to be learned about these neural tumors, which are so central to the disorder, are responsible for much of its medical complications (morbidity), and cause patients such psychological distress. This chapter reviews the classification, natural history, and management options for neurofibromas. Although most are benign, some undergo transformation into malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors (MPNSTs). Neurofibromas can develop at any time in life from the tissue surrounding any nerve in the body. Isolated neurofibromas may develop in people without NF1, but multiple neurofibromas develop only in people with the disorder. Some people with NF1 develop only a handful of neurofibromas, whereas others, though they are the minority, develop thousands—and it is unclear why. The rate of growth may also vary. Some neurofibromas cause no physical effects, whereas others may cause discomfort, disfigurement, and functional impairment. The defining feature of NF1, therefore, is one of its most puzzling to clinicians and vexing to patients. Neurofibroma growth begins in the myelin sheath that surrounds nerves and enables them to send and receive signals more efficiently. As discussed in Chapter 2, electrical impulses are constantly sent back and forth between the brain and spinal cord and the vast peripheral network of nerves that reach every part of the body. This neural communications network enables people to do such things as smell, touch, move, and think. Although it is often compared with the plastic coating in electrical wires, the myelin sheath forms from multiple layers of fatty tissue, which is itself made up of multiple cell types. The neural tumors in NF1 develop when cells in the protective sheath begin to multiply out of control. This most likely occurs because the tumor suppressing effects of the NF1 gene are lost (see Chapter 3). Several different neural tumors may develop in NF1. The type of tumor that develops depends on its location in the body and which cells are involved. The most common are discrete and plexiform neurofibromas that develop in the tissue surrounding peripheral nerves (Fig. 6–1). Figure 6–1 Neurofibromas develop from Schwann cells that make up the protective sheath around nerves. Pathologically, neurofibromas consist of a mixture of many different types of cells, some derived from the nerve sheath itself and others from surrounding tissues and other types of cells (Figs. 6–2 and 6–3). Spindle-shaped cells proliferate abundantly. These include the Schwann cells that help to form the myelin sheath in the peripheral nervous system, and perineural fibroblasts, which are among the most common types of cells that make up the connective tissue surrounding nerves. The tumors also contain mast cells (inflammatory cells that probably exist in multiple tissue types but seem to be notably drawn to neurofibromas), collagen (the supportive protein component of connective tissue and skin, as well as bone and cartilage), and the extracellular matrix (the substance between cells). As the various cells proliferate, the nerve itself is not usually jeopardized. The axons, fiber-like extensions that enable nerve cells to communicate, pass through the developing neurofibroma tumor mass. This stands in contrast to schwannomas, where the proliferating tumor mass displaces axons and thereby impedes nerve function. Discrete neurofibromas are encapsulated; they may grow in size and press on other tissue or bone but will not invade them. Plexiform neurofibromas (Fig. 6–4), on the other hand, are nonencapsulated; they can grow through healthy tissue and interfere with the normal development of bones, which makes management more difficult. Plexiform neurofibromas tend to be supported by a network of blood vessels that supply oxygen and nutrients. Figure 6–4 A dissected plexiform neurofibroma reveals thickened nerve trunks and multiple extensions of the tumor. A “two-hit” loss of the NF1 gene (one an inborn mutation and the other an acquired mutation) in Schwann cells probably initiates the formation of a neurofibroma, but loss of function of one copy of the gene in surrounding cells is also necessary before the tumor can grow (see Chapter 3). Hormones may also contribute to the growth of neurofibromas. Discrete dermal neurofibromas usually first develop around the time of puberty. During pregnancy, both discrete and plexiform neurofibromas tend to increase in size, and dermal neurofibromas may increase in number (see Chapter 9). Until recently the hormonal effects on people with NF1 were anecdotal, although quite voluminous. This situation changed when a study reported that three in four neurofibromas contained molecular receptors for the hormone progesterone, a female sex hormone produced by the ovaries during the menstrual cycle and by the placenta during pregnancy.1 The presence of such receptors indicates that these neurofibromas are sensitive to fluctuations in levels of progesterone and supports the notion that this may be the responsible hormone. It does not, however, completely prove that this hormone (or any hormonal factor) is responsible for neurofibroma growth. Another theory is that additional genetic mutations may contribute to the development and fuel the growth of neurofibromas. The research in this area continues. From a clinical perspective, there are two basic types of neurofibromas, discrete and plexiform, which each have two subtypes. A discrete neurofibroma is a benign tumor that arises from a single site on a peripheral nerve and grows into a rounded mass with well-defined borders. These types of neurofibromas generally begin to appear in late childhood or just before puberty and increase in size and number with age. Discrete neurofibromas rarely, if ever, become malignant. A discrete dermal neurofibroma is one that develops along a nerve in one of the upper layers of the skin (the dermis or epidermis). As dermal neurofibromas grow, they usually protrude above the surrounding skin surface. At first, they may resemble mosquito bites, but they do not itch or subside. With time they may grow larger. Dermal neurofibromas tend to be soft and fleshy to the touch, and the skin covering them may be flesh-colored, pink, or purple. As dermal neurofibromas grow, they may appear either as a rounded sessile mass rising from a broad base on the skin or as a larger mass attached to the skin with a smaller stalk (pedunculated). They may become lobulated, a single lesion divided into small lobes. Sometimes, dermal neurofibromas that develop in the second or third layer of skin rather than the top one will cause an indentation, and the skin covering them will be violet. Although dermal neurofibromas can develop anywhere on or in the body, they tend to develop most often on the chest, abdomen, and back, known collectively as the trunk. The most common pattern of growth is slow, with a limited number of neurofibromas appearing just before puberty and then steadily growing in number and size over a period of years. There are exceptions, however. People who have deletion of the whole NF1 gene (rather than a mutation in part of it) tend to develop a significant number of dermal tumors while they are young. Other people may first develop dermal neurofibromas during their 20s. Sometimes, multiple dermal neurofibromas seem to sprout over a matter of months rather than years. Usually this type of rapid growth subsides. It is also possible that neurofibromas will develop but not progress noticeably during a person’s lifetime. Some women experience neurofibroma growth during pregnancy (see Chapter 9). Dermal neurofibroma growth generally continues through middle age and even beyond, but it tends to stabilize when the person becomes elderly. Depending on their location or number, the major problem that dermal neurofibromas cause is cosmetic, although this term is not meant to trivialize the physical and psychological impact of these lesions. Dermal neurofibromas on the face and neck, and other exposed areas of skin, may be unsightly and cause psychological distress. Dermal neurofibromas are usually not painful, although some people with NF1 experience sharp pain if one is bumped or pressed. Those located on areas rubbed by clothing, such as the collar line or waistline, may cause physical discomfort. Large pedunculated neurofibromas may be accidentally torn off, causing bleeding. Others may be bumped repeatedly, causing pain. That is why some people with NF1 choose to have neurofibromas removed surgically (see below). A subcutaneous neurofibroma is a discrete tumor that develops along a nerve contained in deeper body tissue, located under the epidermis. Discrete subcutaneous neurofibromas are usually firm and rubbery to the touch, and may feel like tiny beads beneath the skin. They may be sensitive and painful when pressure is applied. Although subcutaneous neurofibromas are often visible as bumps, the skin can be moved over them to distinguish them from dermal neurofibromas. Such tumors vary in size, ranging from those that are about as large as peas to those that are several centimeters in diameter. Some are so small that they can be “seen” only at an angle, at certain lights, in which the skin takes on a dappled or pebbly appearance (Fig. 6–5). Other discrete subcutaneous neurofibromas are detected only by palpating the area. It is also possible for discrete subcutaneous neurofibromas to develop in deeper nerves. With time, these may grow enough to compress a nerve root, causing radicular pain (felt at a site distant from the compromised nerve root) and other symptoms. Unusually challenging, in terms of symptoms and management, are discrete subcutaneous neurofibromas that develop in the tissue surrounding nerve roots within the spinal column (Figs. 6–6 and 6–7). With time, the neurofibroma can expand on either side of the neural foramen (the opening through which the nerve enters the spinal cord), taking on a dumbbell shape as it grows. Such neurofibroma growth may compress the nerve root, or the spinal cord itself, resulting in radicular symptoms such as weakness in the limbs, loss of sensation, and pain.2 Figure 6–6 Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan showing a spinal neurofibroma. Figure 6–7 This computed tomography (CT) scan demonstrated a spinal root neurofibroma (closed arrows) pressing on the spinal cord (open arrow). A plexiform neurofibroma grows along the length of a peripheral nerve sheath, rather than being anchored to a single site within the sheath. Plexiform neurofibromas are usually present at birth (although they may not be noticed), grow during childhood, and then stabilize, although there are some exceptions to this general rule. Though most plexiform neurofibromas are benign, some may develop into MPNSTs. Most plexiform neurofibromas that develop in people with NF1 are diffuse in nature (Figs. 6–8, 6–9, and 6–10). As the term implies, a diffuse plexiform neurofibroma is one that spreads out from its area of origin. This type of neurofibroma often develops multiple tumor branches that may engulf additional peripheral nerves or extend into adjacent healthy tissue. Major nerves as well as minor ones can become involved. In many cases, however, the organization of the nerve itself is preserved so that function is not impaired.3(p53)

Neurofibromas and Malignant Peripheral Nerve Sheath Tumors (MPNST) in Neurofibromatosis 1

♦ Neurofibromas: An Overview

Discrete Neurofibromas

Discrete Cutaneous (or Dermal) Neurofibromas

Discrete Subcutaneous Neurofibromas

Plexiform Neurofibromas

Diffuse Plexiform Neurofibromas

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree