SYMPTOMS OF CERVICAL DYSFUNCTION

The principal symptom that provokes a patient to seek medical attention is usually pain. Other symptoms may accompany, including numbness, paresthesias, and weakness, but they are not usually the major concerns in the early stages.

The key discriminating features of pain include the mode of onset (acute, subacute, or chronic), quality (dull, aching, sharp, or stabbing), location at onset and subsequent spread, and factors that alleviate or exacerbate the pain.

Pain of cervical origin can be classified in one or more of the following five categories: (a) local pain, (b) referred pain, (c) radicular pain, (d) funicular pain, and (d) pain due to myospasm (

Table 12.1).

Local pain is of a deep, aching quality that usually does not radiate and is worsened with movement, weight bearing, and palpation of area affected and alleviated by rest. It is the pain most often encountered in cervical spondylosis with or without muscle tension and is also termed mechanical pain. Metastatic disease to the spine often causes local pain that is typically worse at night, with recumbency and rest.

Referred pain may accompany local pain and is usually dull, achy, relatively diffuse, nonradicular, and at times segmental, but difficult to localize. Alleviating and aggravating factors are similar to those found with local pain. A common example is the aching pain in the shoulder and chest from chronic cervical spondylosis. Another example is the shoulder pain caused by irritation of the diaphragm, such as that experienced after an abdominal laparoscopic procedure (

1).

Radicular pain can be divided into two subtypes:

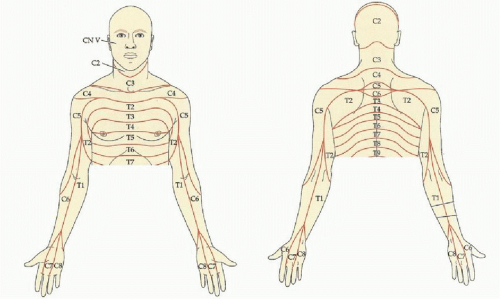

dermatomal and

myotomal. Dermatomal radicular pain develops from irritation of the dorsal nerve roots and as its name indicates follows a dermatomal distribution that facilitates localization (

Fig. 12.1). It is sharp and stabbing and radiates distally to specific areas of the extremity. It is often associated with other sensory symptoms, such as paresthesias, as well as motor dysfunction and reflex abnormalities, and is invariably worsened with anything that compresses or stretches the inflamed nerve root. There may also be a superimposed and more diffuse, chronic ache that is thought to arise from the ventral spinal root and follows a myotomal distribution (

2) (

Table 12.2). An example is “cervical angina” that is believed to be caused by irritation of the ventral nerve roots of C6-C8. Radicular pain is most often encountered in cervical disk disease with the dorsal nerve roots of C6 and C7 being most commonly involved. It is less likely in tumors associated with metastasis and neurofibromas.

Funicular pain is due to dysfunction of the intraspinal sensory pathways, either the spinothalamic tract or the posterior columns. It is characteristically diffuse, burning, and sometimes knife-like and localized on the trunk or extremity. Provocation includes tactile stimulation, flexion of the neck, or anything that distorts ascending pathways. A form of this pain occurs with neck flexion that causes the cord to stretch producing an electric-like sensation in spine or limbs known as Lhermitte’s sign (

3). The most usual cause of this unusual pain is an intramedullary lesion, such as demyelination, syrinx, spinal cord tumor, or myelitis, and compressive lesions, such as cervical spondylosis.

Pain due to myospasm is among the most common causes of neck pain. The onset may be acute or gradual. It may be localized or referred and often is associated with muscle tenderness and spasm, limited range of motion (ROM), and tender trigger points, as in the myofascial pain syndromes (

1).

In addition to pain, other sensory symptoms that may be helpful in diagnosis and localization include paresthesias, dysesthesias, and numbness. Paresthesias (pins and needles sensation) and dysesthesias (irritative sensation) are more frequent than absence of sensation. In radiculopathies, the location of the paresthesias is helpful in localization but at time may not match the exact dermatome. This is thought to be due to overlap of peripheral nerve territories in the arm and central representation (

4). Isolated paresthesias of the thumb indicate a C6 root lesion, paresthesias of any combination of digits two to four suggest

a C7 lesion, and paresthesias of the fifth digit suggest the C8-T1 level.

The other major symptom is weakness and at least acutely is less common than pain and paresthesias. This is sometimes a difficult symptom to assess, especially in the presence of pain, because of incomplete voluntary effort due to guarding. It is also often less helpful in the diagnosis of radiculopathy because of myotomal overlap. Nonetheless, the pattern may be diagnostic, such as the shoulder girdle weakness and scapular winging that occur after the severe pain of acute brachial plexitis.

PRINCIPLES OF THE EXAMINATION

Prior to examining a patient, a thorough history should be obtained. This must include symptom location, character, onset, duration, as well as aggravating and alleviating factors such as if symptoms are worsened by Valsalva-type maneuvers or while recumbent. This will not only help identify the source of the symptoms but also help tailor the physical exam, which is the first basic principle. The second basic principle is that the examination be thorough. In an era of high-resolution imaging, there is a growing tendency to minimize this principle. Nowhere is this more treacherous and misleading than in cervical spinal cord disorders.

The examination begins with the observation of how the patient holds his or her neck during the history taking and of how freely the neck moves when the patient is distracted and does not realize he is being observed. A focused general physical examination should also take place. One should take care to listen to heart and lung sounds, as well as examine the chest wall for restricted

motion. At the same time, palpate the supraclavicular fossae for abnormal or firm masses and vascular structures that may suggest an etiology outside the cervical spine.

Musculoskeletal examination includes palpation and percussion of the spine, as well as passive and active ROM testing (

1). If pain is elicited, it is suggestive of a structural lesion. Observe for limited motion in one direction or another and estimate or measure the degree of limitation. Localized muscle tenderness is a useful observation in neck pain, especially if the spontaneous pain can be recreated.

In patients with upper limb pain, it is important to exclude local structural limb and joint pathology. This includes use of passive and active ROM of the shoulder, elbow, and wrist as well as careful palpation over the acromioclavicular joint and the ventral aspect of the shoulder for bicipital tendonitis (

5). The shoulder abduction relief test can be used to identify cervical monoradiculopathies due to extradural compressive disease. This is done by having the patient abduct the shoulder with elbow flexed; a positive test is considered if the pain resolves in this position. If from the same position the elbow is extended and externally rotated resulting in increased pain, it is suggestive of a cervical root or brachial plexus disorder (

Table 12.3). Consider rotator cuff pathology if attempts to abduct the shoulder result in pain (

1).

In the forearm, radiohumeral bursitis (lateral epicondylitis, “tennis elbow”) might be confused with a C6 radiculopathy. The diagnosis of lateral epicondylitis is suspected by observing the inability to extend fully the elbow actively or passively because of pain. Hand grasp results in pain due to tightening of the extensor wrist tendons as the wrist reflexly extends. Localized tenderness just distal to the radial aspect of the elbow is a useful sign. A similar but less frequent source of forearm pain that may be mistaken for a C8-T1 radiculopathy is medial epicondylitis (reverse tennis elbow, golfer’s elbow). The pain in this condition is about the medial epicondyle with wrist extension.

Local wrist pathology may be confused with a radicular process and is sometimes caused by de Quervain’s disease when it radiates into the thumb, radial wrist, and forearm. In addition to tenderness over the tendons, pain is increased when the hand is forcibly ulnar-deviated with the thumb flexed and adducted (Finkelstein maneuver). Carpal tunnel syndrome (CTS) and de Quervain’s synovitis can often coexist (

2).

In the Spurling maneuver, the neck is extended and the chin rotated toward the side of the limb pain along with simultaneous downward compression of the head. A positive result with the reproduction of the radicular pain is due to nerve root compression (

7). Accentuation of the neck pain is not diagnostic. The arm pain must be aggravated or elicited to be considered useful. The Naffziger sign is another potentially helpful test when a radicular pain source is sought. A positive result consists of reproducing the arm pain after digital pressure over the internal jugular veins for several seconds or until the head feels full. The mechanism for the pain is due to increased intracranial and intraspinal pressure resulting in accentuated traction of inflamed nerve roots.

The controversial thoracic outlet syndrome (TOS) is another entity that should be considered in the differential diagnosis of limb pain. The symptoms may be neurologic (true neurogenic TOS) or vascular (vascular TOS). The symptoms relate to the distal limb (forearm and fingers) rather than neck, shoulder, and arm. In most, the neurologic symptoms are not persistent and are due to compression of lower trunk of the brachial plexus as it passes between the clavicle and first rib and is caused by a cervical rib, large C7 transverse process, a ligamentous band, or a hypertrophied scalene muscle. TOS may be confused with a C8-T1 radiculopathy because of the sensory symptoms on the medial side of the forearm, hand, and fourth and fifth fingers (

Fig. 12.2).

In vascular TOS, ischemic symptoms occur due to compression of the subclavian artery or vein, by the same process as in neurogenic TOS. With arterial compression, the affected arm may have intermittent symptoms of coldness, cyanosis, and pallor. Raynaud’s phenomenon and ischemic digits from mural thrombi embolization due to poststenotic dilation of the subclavian artery is a rare event. With venous compression, the affected limb may develop edema as well as prominent veins in the arm and chest. Careful inspection of the upper arm and chest for venous dilation usually is sufficient to exclude it (

3,

8). If TOS is a consideration, blood pressure recordings in both arms and auscultation for bruit above and below the clavicle are necessary. Careful palpation of the supraclavicular fossa is required, looking for a bony protuberance from a cervical rib, an anomalous first rib, or an enlarged firm mass from lung cancer. Next, the radial pulse is felt during neck extension with the chin rotated toward the side and with full expansion of the chest (Adson maneuver). Another maneuver, the costoclavicular maneuver, involves adduction of the arms to the side and active retraction of the scapulae while palpating both radial pulses. With either maneuver, the result is clinically important only when the appropriate pulse is diminished and the neurologic signs or symptoms are reproduced.

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access