Figure 62.1. CT with contrast, showing hypodensity in the right cerebral peduncle and periventricular corona radiata with mild mass effect and patchy rim enhancement (A, C), as well as a hyperdense calcification in the right thalamus (B).

Figure 62.2. CT with contrast, showing hypodensity in the right cerebral peduncle and periventricular corona radiata with mild mass effect and patchy rim enhancement (A, C), as well as a hyperdense calcification in the right thalamus (B).

Antiepileptic drugs (AEDs) may be used for secondary prophylaxis but they are not routinely used for primary prophylaxis. Given the hepatic metabolism and toxicity of the TE antimicrobials, AEDs with lower hepatic toxicity and enzyme induction should be preferred (i.e., levetiracetam). The vast majority of patients will show significant improvement clinically and radiographically within 2-3 weeks (Figure 62.3). Failure to do so should strongly suggests an alternative diagnosis.

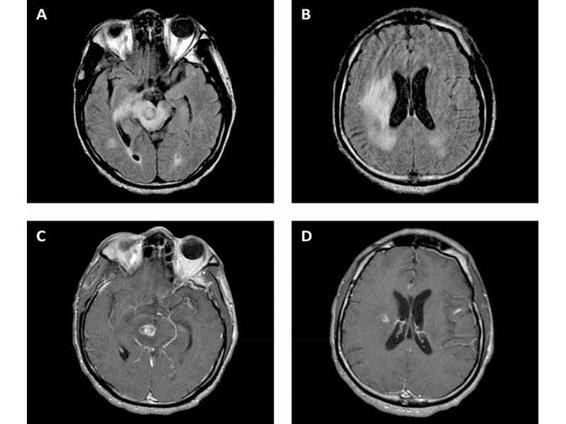

Figure 62.3. Toxoplasmosis. Fluid attenuated inversion recovery (A, B) and T1 post contrast (C, D) MRI showing improvement in T2 hyperintensity in the right cerebral peduncle and periventricular corona radiata with mild mass effect and patchy rim enhancement 4 weeks after starting treatment.

Primary CNS lymphoma is the second most common cause of focal brain lesions in HIV. In patients with HIV, PCNSL is associated with Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) infection, as opposed to PCNSL in non-immunocompromised patients. Histopathology typically reveals a large B-cell lymphoma. Presenting symptoms are nonspecific; a majority of patients present with mental status changes such as lethargy, confusion, memory loss, and behavioural changes. Furthermore, up to 80% of patients have a history of constitutional symptoms, including fever, night sweats, weight loss, and fatigue (which are common in advanced HIV as well). Focal symptoms, including hemiparesis, aphasia, ataxia, and cranial nerve deficits are also common, but patients may lack clear localizing symptoms and signs. Symptoms are typically present for days to weeks before diagnosis. Patients are profoundly immunosuppressed with CD4 usually <50 cells/μl. CT and MRI reveal a wide spectrum of findings, including solitary or multifocal lesions; ring, patchy, or homogenous enhancement; and cortical or subcortical location (Figure 62.4).

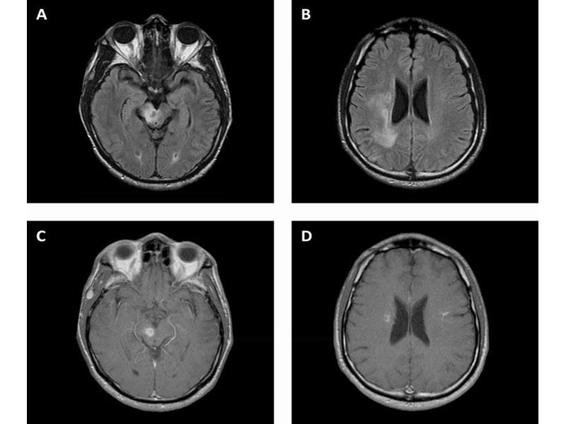

Figure 62.4. Primary central nervous system lymphoma. FLAIR (A, B, C) and T1 post-contrast (D, E, F) MRI showing T2 hyperintense lesion with patchy rim enhancement and surrounding edema in the right midbrain and basal ganglia with extension across the genu and splenium of the corpus callosum.

Compared to non-immunocompromised patients, PCNSL in HIV is more likely to be multifocal, found in cortical as well as deep locations, and with less homogenous enhancement (due to central necrosis from rapid growth). Radiographic appearance is not reliable in terms of differentiating PCNSL from TE or other infections, but in general PCNSL is more likely to involve periventricular and corpus callosum white matter and less likely to involve the posterior fossa than TE. Metabolic imaging including single-photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) has been used in some studies to differentiate PCNSL from other causes of mass lesions, but these technologies are not widely available or validated. Given the strict association with EBV, the presence of EBV DNA on PCR assay of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) lends strong supportive evidence for PCNSL. CSF cytology may be diagnostic, but its sensitivity is poor as only a minority of PCNSL have leptomeningeal involvement. While up to 25% of non-HIV-associated PCNSL may include ocular involvement, ocular spread is not well established in HIV so that the yield of ophthalmological examination is low. Some clues in favour of PCNSL over TE include negative toxoplasma serology, adherence to prophylactic TMP-SMX, and lack of response to specific treatment for TE. The combination of negative toxoplasma serology and positive CSF EBV DNA PCR should strongly support the diagnosis of PCNSL in these patients. In many cases, however, biopsy is necessary to confirm the diagnosis prior to initiating potentially toxic therapies. It is important to note that the administration of corticosteroids prior to biopsy to reduce mass effect may compromise the diagnostic yield as PCNSL may rapidly but temporarily shrink in response to corticosteroids. HIV-related PCNSL has traditionally been treated with whole brain radiation combined with corticosteroids with modest benefit and significant neurotoxicity in the few who survive long enough. The median survival in untreated PCNSL is 1 month, and with radiation this is extended to 2-5 months (often due to other opportunistic infections). Chemotherapy has been avoided due to the already profound immunocompromised state of these patients. However, with the advent of effective combination antiretroviral therapy (cART), survival in PCNSL has improved. Furthermore, high-dose methotrexate, which has become standard therapy in non-HIV PCNSL, has also been shown to improve survival with fewer neurotoxic effects compared to radiation. In practice, some combination of cART, methotrexate, and radiation is often used, depending on patient characteristics.

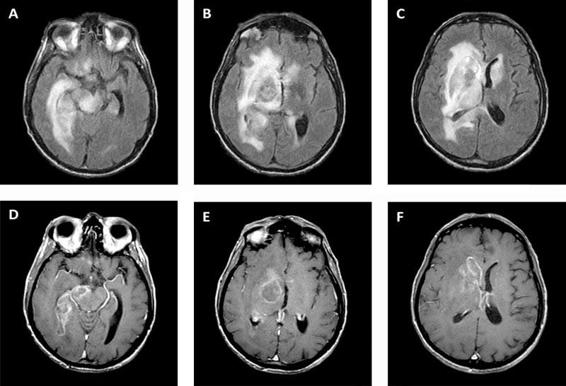

The third most frequent cause of focal brain lesions in HIV is PML. The JC virus (or John Cunningham virus) is a polyomavirus typically acquired in childhood and which remains latent in the kidneys, blood, and lymphoid organs. Up to 86% of normal subjects in Europe had antibodies to JCV. In the setting of immunocompromisation from HIV (also in hematologic malignancy or treatment with immunosuppressive medications), JCV may reactivate with a tropism for the cerebral white matter. This usually occurs with CD4 counts <200 cells/μl. It infects the oligodendrocytes, causing lysis and demyelination. Compared to TE and PCNSL, PML presents more insidiously over weeks to months. Patients present with focal deficits, including hemiparesis, ataxia, visual field deficits, and diplopia. Altered mental status is common, but cognitive impairment in the absence of focal findings on exam or imaging is unusual. Cortical symptoms and signs, including seizures, frequently occur due to involvement of the juxtacortical white matter and the gray matter itself. While TE and PCNSL are characterized by contrast enhancement and mass effect on neuro-imaging, PML typically lacks these features. Classically, PML appears as asymmetric multifocal white matter lesions which do not respect vascular territories and lack contrast enhancement or mass effect. Lesions are hypodense on CT; MRI reveals hyperintense lesions on T2-weighted and hypointense lesions on T1-weighted images (Figure 62.5).

Figure 62.5. Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy. FLAIR (A) and T1 post-contrast (B) MRI showing multifocal T2 hyperintense lesion in the right frontal and parietal subcortical white matter, with corresponding T1 hypointensity but no enhancement or mass effect.

While lesions most commonly involve the periventricular and subcortical white matter, posterior fossa and basal ganglia lesions frequently occur. Brain biopsy reveals gross demyelination and histopathology shows oligodendrocytes with nuclear inclusions and atypical astrocytes. Immunohistochemistry staining for JCV identifies infected oligodendrocytes. Development and validation of PCR for CSF JCV DNA has obviated the need for brain biopsy in most HIV patients with PML. Before the advent of highly active anti-retroviral therapy (HAART), CSF PCR for JCV had 72-92% sensitivity and 92-100% specificity; sensitivity is decreased in patients on ART. In cases with typical clinical and radiographic features, positive CSF JCV PCR is considered diagnostic. Even when CSF is negative, a presumptive diagnosis may be given if other etiologies are excluded. There is no effective JCV specific treatment available, but in HIV patients, reconstitution of the immune system with effective ART has led to great improvements in survival. Prior to HAART, the 1-year survival rate in patients with PML was only 10%; more recently this has improved to at least 50%. Even with longer survival, however, lesions caused by PML tend to persist, leaving residual deficits. A more recently recognized presentation occurs when there is a robust immune response – in the setting of IRIS from effective ART – which leads to symptomatic presentation of previously undiagnosed PML or worsening of known PML, with enhancement and edema on neuro-imaging. Although symptoms may worsen, this inflammation confers an improved prognosis for survival. Corticosteroids may be used cautiously in cases where this inflammation threatens essential neurological structures.

Although TE, PML, and PCNSL constitute the most common etiologies for focal brain lesions in patients with HIV, such patients are also at increased risk for other infections and for unusual manifestations of non-HIV-related infections. In many parts of the world, tuberculosis is an important cause of focal CNS lesions. Its incidence is increased further in patients with HIV, even at CD4 counts >200 cells/μl. Patients with HIV started on ART with virologic and immunologic improvement may unmask a previously asymptomatic tuberculoma. Distinguishing these lesions from toxoplasmosis or neurocysticercosis can be particularly difficult, and biopsy is often required. While HIV does not increase the risk for neurocysticercosis, it may alter the presentation of this disease endemic to Latin America. There is some evidence suggesting that giant cysts and the racemose form of neurocysticercosis are more common in HIV-positive patients, possibly due to reduced immunity that allows for more chronic expansion of the cysts. In some cases, neurocysticercosis may be incidentally noted when imaging is obtained due to another HIV-related focal brain lesion. Rarer causes of focal brain lesions in HIV include fungal abscesses, including cryptococcus and histoplasmosis; aspergillosis may rarely cause a brain abscess in patients with HIV. Pyogenic bacteria, as well as atypical bacteria such as nocardia, are infrequent causes of focal brain lesions in HIV patients but are more common in injection drug users.

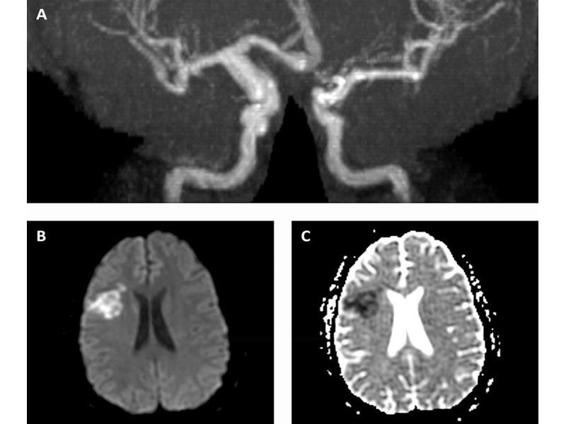

Occasionally, cerebral infarction is the presenting symptom of HIV or occurs in the course of known HIV infection. Basal meningitis/vasculitis due to tuberculosis, syphilis, and fungal infections – along with intracerebral vasculitis due to varicella-zoster virus (VZV) – are the usual etiologies for infarction. An unusual dilated cerebral arteriopathy affecting the extracranial and intracranial arterial stems and causing fusiform aneurysms has been increasingly recognized in patients with HIV and should be considered in the differential diagnosis of stroke of unknown etiology in young adults (Figure 62.6).

Figure 62.6. HIV-arteriopathy. MRA circle of Willis (A) showing distal right ICA and proximal right MCA fusiform dilatation; diffusion weighted imaging (B) and apparent diffusion coefficient (C) sequences showing right MCA territory acute infarction.

62.3 Diffuse Encephalitis

In addition to focal brain lesions, HIV patients are at risk for a number of more diffuse encephalitic processes. Acute HIV infection (or viral rebound from poor adherence or viral resistance) may rarely manifest with a fulminant HIV encephalitis (direct infection) or a peri- or post-infectious acute demyelinating encephalomyelitis (ADEM). Patients with more advanced HIV often develop HIV-associated dementia (HAD). Rarer causes of diffuse encephalitis in late HIV include cytomegalovirus (CMV), varicella-zoster virus (VZV), and neurosyphilis. Finally, in settings where patients have access to effective ART, longer survival has led to more typical causes of dementia in aging populations.

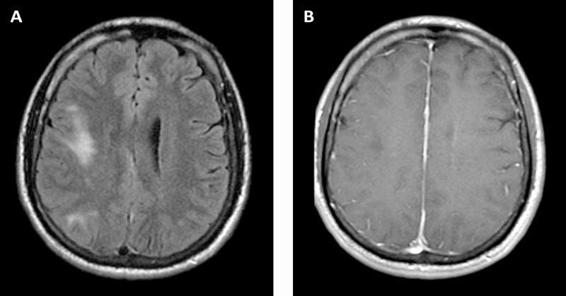

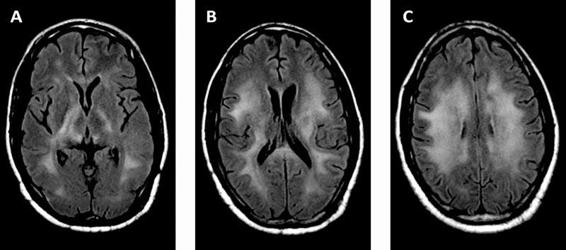

Among the processes that cause diffuse encephalitis in patients with HIV, the most frequent is HAD. This is typically a slowly progressive subcortical dementing process. As such, neurological sequelae from HAD will rarely require neurological-ICU care. Familiarity with this entity is nonetheless important for intensivists as these patients often have advanced disease and multiple simultaneous processes. HIV gains access to the CNS early in the course of infection via migration of infected monocytes. Replication within the CNS occurs in the microglia and macrophages. Damage occurs indirectly from cytokine-induced cytotoxicity. Early in the course of HAD, deficits develop in concentration, short-term memory, cognitive slowing, apathy, reading, and comprehension. Later on, patients may develop more florid dementia and frontal release signs. These are often accompanied by motor deficits which are predominantly extra-pyramidal. Neuro-imaging may reveal cortical and periventricular atrophy; often there is diffuse, symmetric subcortical white matter hypodensity on CT or hyperintensity on T2-weighted MRI (Figure 62.7). Compared to PML, lesions due to HAD are more often symmetric, may be isointense on T1-weighted MRI, and are potentially reversible. In untreated patients, HAD usually presents in advanced disease (CD4 count <150 cells/μl). But more recently with ART the proportion of cases presenting with CD4 counts of 200-350 cells/μl is increasing. CSF studies are nonspecific and may even be normal. The HIV viral load may be detectable, sometimes at high titres, in the CSF. In patients on ART, however, the CSF viral load does not correlate with HAD. Although biopsy may be unnecessary, classic pathology on brain biopsy or autopsy reveals multinucleated giant cells and myelin pallor. While there are proposed criteria for diagnosis, HAD is ultimately a diagnosis of exclusion. Treatment with ART with suppression of serum viral load may lead to stabilization or even reversal; treatment is less effective late in the disease when significant atrophy is already present. There is ongoing debate on whether ART regimens with better CNS penetration (as measured in CSF) improve outcome.

Figure 62.7. HIV-associated dementia. FLAIR MRI showing symmetric, confluent T2 hyperintense signal in subcortical white matter (A, B, C); there was no corresponding enhancement or mass effect.

Rarely HIV can cause a more fulminant meningoencephalitis. In HIV seroconversion, patients may present with an acute disseminated encephalomyelitis (ADEM)-like illness. In addition, in the setting of viral rebound due to cessation of ART or viral breakthrough due to the development of resistance to ART, patients may develop meningoencephalitis with a high CSF viral load. In both these scenarios, patients may improve rapidly with (re-)initiation of ART. More recently, it has been recognized that immune reconstitution from effective ART can lead to an exaggerated inflammatory response in the CNS, often in a similar but more fulminant pattern to HAD. This process often proves rapidly fatal, and steroids may be given in an attempt to attenuate the exaggerated immune response.

Cytomegalovirus (CMV) is a herpes virus that may be reactivated in profoundly immunocompromised patients (CD4 count <50 cells/μl) to cause neurologic disease in the retina, brain, spinal cord, nerve root, or peripheral nerves. Non-nervous system involvement includes colitis, esophagitis, and rarely pneumonitis. While the incidence of CMV disease in HIV has declined in populations with access to ART, it remains an important consideration in cases of diffuse encephalitis in immunocompromised patients. CMV encephalitis may present with subacute dementia similar to HAD but usually more rapid and more likely to have accompanying focal symptoms and signs. CMV ventriculo-encephalitis is a more fulminant syndrome, with accompanying focal signs including cranial nerve palsies, and is rapidly fatal. Patients with CMV encephalitis often have evidence of CMV disease elsewhere, especially retinitis. CT and MRI may reveal periventricular enhancement. The typical CSF profile is nonspecific, usually with mild-moderate pleiocytosis, normal to low glucose, and moderately elevated protein. In the appropriate clinical context, diagnosis is made by CSF CMV antigen testing or DNA PCR. Treatment consists of intravenous ganciclovir 5 mg/kg q12 and foscarnet 60 mg/kg q12 until improvement, with initiation of ART if there is a clinical response. Lifelong maintenance consists of oral valacyclovir 900 mg daily.

VZV is ubiquitous throughout temperate climates. Primary infection causes chicken pox, with latent virus persisting in the dorsal root and cranial nerve ganglia. Reactivation in the elderly and immunocompromised leads to herpes zoster or shingles. Patients with HIV have a 15-fold increase in zoster, which may occur at any CD4 count but usually when <200 cells/μl. VZV may rarely manifest as a neurologic syndrome, including encephalitis, myelitis, meningitis, retinitis, cranial nerve palsy, CNS vasculitis, or a combination thereof. Neurological involvement in zoster is more common in HIV than in other patients. Rash may not be present in a significant minority, so its absence does not exclude VZV as a cause of neurological symptoms. CSF typically reveals a mild lymphocytic pleiocytosis, moderately elevated protein, and normal glucose. CSF VZV DNA PCR or antibodies confirm the diagnosis. MRI may show multifocal T2 hyperintensities and leptomeningeal enhancement, but such findings are nonspecific and may be normal. In VZV vasculitis, MRI may show single or multifocal cerebral infarctions, so VZV should be considered in the differential diagnosis of stroke syndromes in HIV patients. Treatment with intravenous acyclovir usually leads to recovery, except for visual loss from retinitis and infarctions from vasculopathy.

62.4 Meningitis

Meningitis is a frequent complication of advanced HIV. In patients with CD4 counts <200 cells/μl, the most common cause of meningitis is Cryptococcus neoformans, followed by tuberculosis and syphilis. HIV itself causes aseptic meningitis at seroconversion in up to one third of patients, which is usually self-limiting, as well as a rebound meningoencephalitis as noted above. Less common causes of meningitis include coccidioides, VZV, HSV-2, and pyogenic bacteria. Non-infectious meningitis may occur with leptomeningeal spread of systemic non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Patients with advanced HIV may not present with classic symptoms and signs of meningitis, so the threshold for performing lumbar puncture to assess neurological symptoms should be lower for these patients. As these patients may also have multiple simultaneous neurological processes, neuro-imaging should be performed prior to lumbar puncture when possible to exclude mass lesions which might lead to downward herniation if CSF pressure is decreased.

C. neoformans is a ubiquitous encapsulated yeast found in the soil worldwide, as well as in pigeon droppings. This invasive fungus infects humans through the lungs, but the most common clinical manifestation is meningitis (meningoencephalitis), likely related to decreased complement activation and other factors that allow more growth in the CSF. It predominately affects immunocompromised patients; HIV patients with cryptococcal meningitis typically have CD4 counts <100 cells/μl, although it can rarely occur at higher counts. The incidence has decreased in populations with access to ART. Due to the lack of appropriate immune response, patients develop symptoms over days to weeks. Fever, malaise, and headache are the most common presenting symptoms, with classic symptoms of meningitis, as well as altered mental status, occurring in only about 25% on presentation. Rarely, patients may present with focal findings due to a mass lesion or cryptococcoma, usually in the deep white matter or basal ganglia, which occurs more often in non-HIV patients. Hence, mass lesions in patients with cryptococcal meningitis are more likely to be due to one of the causes listed in the section above. In some patients, cranial nerve palsies such as bilateral blindness and deafness can be presenting symptoms with only slight meningeal symptoms, due to the predilection of the infection to the CSF cisterns at the base of the brain. CT and MRI may be normal, but contrast studies may reveal perivascular nodules. CSF opening pressure is almost always elevated, often markedly so. CSF is often bland, with up to 30% of patients having normal CSF profiles. CSF India ink stain reveals numerous encapsulated yeast in 80% of cases. CSF cryptococcal antigen assay is highly sensitive and specific and is much more rapid than culture. Serum cryptococcal antigen assay is similarly sensitive in HIV patients and useful when lumbar puncture cannot be done immediately. Cryptococcal meningitis in HIV is treated with intravenous amphotericin B (0.7 mg/kg/day) plus oral flucytosine (100 mg/kg/day in 4 divided doses) for 14 days as induction. Consolidation treatment consists of oral fluconazole (400 mg/day) for at least 8 weeks. Once there is clinical improvement after 10 weeks, oral fluconazole (200 mg/day) provides maintenance therapy, which is continued indefinitely although discontinuation may be considered after ART leads to CD4 counts >100 cells/μl for at least 12 months. Even with successful chemotherapeutic treatment of cryptococcus, increased intracranial pressure (ICP) can pose ongoing problems. Patients may require daily lumbar puncture to remove enough CSF to maintain closing pressure <200 mmH2O; patients who have ongoing elevated ICP after 4 weeks often require a ventriculoperitoneal shunt. Some patients without known cryptococcal meningitis, or with previously treated disease, may show worsening meningitis with inflammatory CSF in the setting of effective ART. This IRIS meningitis may be difficult to distinguish from worsening infection, but usually the organism burden is lower or undetectable in CSF and virologic and immunologic parameters show marked improvement. The timing of initiating ART in patients treated for cryptococcus is controversial, but waiting 2 weeks after specific cryptococcal treatment is reasonable.

HIV itself causes self-limiting aseptic meningitis in up to 30% of cases during acute seroconversion, but it may also persist as a low-grade chronic meningitis that is often asymptomatic. Symptoms include headache, meningismus, malaise, and photophobia. Focal symptoms are rare but may include cranial nerve deficits including bilateral facial palsies; few cases of encephalopathy have been reported. CSF reveals a mild lymphocytic pleiocytosis, normal glucose, and normal to mildly elevated protein. The CSF HIV viral load may be detectable and markedly high in some cases. Except in severe cases, the course is self-limiting and not an indication for initiation of ART (although the issue of starting ART early to reduce CNS penetration is under debate). As mentioned above, rebound HIV meningitis may occur in the setting of viral breakthrough from ART discontinuation or development of resistance. It is rapidly reversible with appropriate ART.

Coccidioides (C. immitis in California and C. posadasii in the American southwest, and Central and South America) are dimorphic fungi limited to arid and semi-arid regions of the Western hemisphere which infect humans by inhalation of spores. In normal hosts, it may cause a self-limiting respiratory illness. In immunocompromised patients, however, there is an increased risk for extrapulmonary dissemination during primary infection or through reactivation. Of these, meningitis is the most serious. Patients may present weeks to months after initial infection, most often with persistent headache. Tremor may be the only other neurological symptom, and overt signs of meningismus are often lacking. Later in the course of disease, cranial neuropathies and focal infarct may occur due to inflammation at the base of the brain with vasculopathy of the basal vessels. MRI may show nonspecific signs of basal meningitis, including leptomeningeal enhancement, infarction, and hydrocephalus. CSF studies show a mild to moderate lymphocytic pleiocytosis; although there may be neutrophilic predominance, early and mild eosinophilia is common. Compared to most other causes of aseptic meningitis, CSF glucose is more often depressed, sometimes markedly. CSF protein is moderately to severely elevated. Coccidioides symptoms and CSF profile can mimic tuberculosis and are both endemic in certain areas of Central and South America, so caution is warranted in the diagnosis. CSF culture of coccidioides is diagnostic but insensitive. Detection of antibodies to coccidioides more often yields the diagnosis, and rarely infection must be inferred from detection at another site or in serum. Meningitis is treated with intravenous or oral fluconazole 400-800 mg daily acutely and 400 mg daily for life thereafter.

Meningitis is the most common CNS manifestation of tuberculosis and it is a major cause of HIV-associated meningitis in endemic areas. Syphilis more often progresses to early neurosyphilis in patients with HIV, requiring more aggressive diagnosis and treatment of syphilis in these patients. Organisms causing meningitis in immunocompetent hosts may also affect patients with HIV, and CSF should be routinely checked for pyogenic bacteria, mycobacteria, venereal disease research laboratory (VDRL) test, VZV, and HSV-2 as these have specific treatments. In addition, neoplastic meningitis – in particular leptomeningeal spread of systemic lymphoma – may cause subacute meningitis with cranial nerve palsies and/or polyradiculitis. CSF should be sent for cytology and flow cytometry where available. Unfortunately, leptomeningeal spread portends a poor prognosis even with appropriate treatment.

62.5 Myeloradiculitis

The most common myelopathy in patients with advanced disease is HIV vacuolar myelopathy. It has been detected in 25-50% of patients with AIDS, although it is symptomatic in only 5-10%. CMV is a rare but important cause of acute myelopathy in patients with advanced HIV and may cause conus medullaris or cauda equina syndrome. Other causes of myelopathy include human T-cell lymphotrophic virus-1 (HTL-1), tuberculosis, syphilis, toxoplasmosis, VZV, HSV-2, vitamin B12 deficiency, and lymphoma.

HIV vacuolar myelopathy shares features in common with subacute combined degeneration. HIV causes vacuolization of the lateral and posterior columns – particularly in the thoracic region – through unknown but indirect mechanisms rather than direct infection. It usually accompanies HIV-associated dementia. Patients present with slowly progressive but painless spastic paraparesis, sensory ataxia, and neurogenic bladder and sexual dysfunction. Rarely acute HIV infection is associated with an acute transverse myelitis, likely due to immune dysregulation. As with encephalitis, rebound viraemia in the setting of ART cessation or development of resistance may occasionally cause an acute myelitis. MRI in vacuolar myelopathy is most often normal but early in the process may show increased signal in the posterior and lateral columns and later may show atrophy of the thoracic cord. CSF typically reveals no white blood cells and mildly elevated protein. There is no specific treatment for HIV vacuolar myelopathy. By the time it is clinically manifest, irreversible damage has occurred. ART may help prevent progression, and typical symptomatic treatments for myelopathy should be applied. There is some evidence that methionine may offer some modest benefit.

CMV may cause axonal destruction, demyelination, or perineural vasculitis. Patients with CMV myeloradiculitis present over days to weeks with lower extremity weakness, saddle anaesthesia, and bowel and bladder paresis producing an acute conus medullaris or cauda equina syndrome. Reflexes are increased in myelitis and absent in polyradiculitis, which is often painful. Patients may have concomitant retinitis or encephalitis. MRI may be normal or show enlargement and enhancement of conus medullaris or cauda equina. CSF studies reveal moderate pleiocytosis (may be neutrophilic or lymphocytic), elevated protein, and normal to low glucose. Diagnosis is confirmed by CSF CMV DNA PCR, which has high sensitivity and specificity in the appropriate clinical setting. Treatment is the same as for CMV encephalitis (see above).

HTLV-1 causes a myelopathy which progresses over many years, ultimately resulting in symmetric spastic paraparesis, bladder dysfunction, and often lumbar and radicular pain. Other causes of chronic myelopathy include tuberculosis, syphilis, subacute combined degeneration, and epidural compression from lymphoma. Acute myelitis may occur in the setting of infection with VZV, HSV-2, and syphilis. Appropriate serum and CSF studies should be sent to assess for these.

62.6 Peripheral Nervous System

While peripheral nervous system disease rarely causes acute critical illness, these syndromes are important to recognize. They may complicate the evaluation of weakness or sensory change in critically ill patients, and rarely may progress rapidly, leading to respiratory weakness and other serious complications.

The most common neurological complication of HIV infection is a distal symmetric polyneuropathy (DSPN) which primarily affects the sensory nerves. The virus causes a toxic dying back neuropathy through indirect immune activation and inflammation. Patients present with burning dysesthesias on the soles of the feet, decreased sensation in the distal lower extremities (especially vibration), and loss of ankle deep tendon reflexes. Certain ART medications – especially the dideoxnucleosides stavudine (d4T) and didanosine (ddI) – cause a toxic neuropathy indistinguishable from DSPN. The frequency with which this complication occurs may obscure the diagnosis of other causes of sensory loss, weakness, or ataxia such as myelopathy or critical illness neuropathy or myopathy.

Both acute and chronic demyelinating polyradiculoneuropathies occur in patients with HIV. Early in the infection, Guillain-Barré syndrome (GBS) may occur in the setting of seroconversion or as the first sign of HIV. GBS may rarely result from immune reconstitution with effective ART. In more advanced HIV infection, patients more often develop chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyradiculoneuropathy (CIDP). The clinical presentation of GBS and CIDP in patients with HIV is similar to that in non-infected patients, and the treatment and favourable response are the same. Clinical features and treatment of inflammatory demyelinating polyradiculoneuropathies are discussed elsewhere.

Mononeuropathy is rare but may occur at any point in the course of HIV infection. Compression may be related to cachexia or in presymptomatic nerve toxicity as in diabetes. Mononeuropathy may also develop into mononeuritis multiplex. Early in HV infection it is likely due to autoimmune vasculitis and has a good prognosis. In more advanced HIV, opportunistic infections including CMV, VZV, and hepatitis B and C play a more prominent role. These viruses should be sought and treated if present. If no explanation is found, biopsy may be necessary to assess for CMV inclusions or vasculitis. In more severe disease associated with vasculitis, treatment with immunomodulation (plasma exchange, intravenous immune globulin, or prednisone) may be helpful but prognosis is poor.

Some patients with HIV develop sicca symptoms with a Sjögren’s-like syndrome with a CD8+ lymphocytosis infiltrating various tissues, including parotid gland, lung, kidney, and peripheral nerve. This diffuse infiltrative lymphocytosis syndrome (DILS) can cause an axonal neuropathy with pain and symmetric sensory loss or a picture of painful mononeuritis multiplex. Blood CD8 counts are elevated above 1200 cells/μl with a CD8 percentage >60%. Treatment consists of ART and/or steroids with typically good response.

Myopathy in HIV may be due to several different processes. HIV myopathy is a presumably immune mediated inflammatory myopathy which may occur at any point in the course of infection. It has clinical and pathologic characteristics similar to non-HIV polymyositis. Patients present with proximal lower more than upper extremity weakness, muscle pain, and tenderness. Creatinine kinase (CK) is often elevated but may be normal. Electromyography (EMG) may be normal but often reveals changes consistent with necrotic myopathy (increased insertional activity, fibrillations, and polyphasic potentials). Muscle biopsy reveals mononuclear endomysial infiltrate, with predominantly CD8+ T cells and macrophages. Once other causes are excluded, treatment is similar to non-HIV polymyositis with high-dose prednisone slowly tapered after maximal response.

Zidovudine, a nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor, may cause a toxic myopathy clinically indistinguishable from HIV myopathy. The pattern of weakness and CK elevation are similar. EMG and basic histopathology are typically milder than HIV myopathy, although evidence of mitochondrial toxicity may be apparent, with ragged red fibres on trichome stain and ultrastructural damage in electron microscopy. Cessation of the offending agent generally leads to recovery over many weeks.

Bacterial pyomyositis usually causes more focal muscle disease, and inflammatory changes overshadow any accompanying weakness. Toxoplasmosis may cause a more diffuse myositis, usually in the setting of disseminated disease including encephalitis. Muscle biopsy reveals more neutrophilic infiltrate and intracellular cysts containing the parasite, if seen, are diagnostic. Treatment is similar for CNS disease (see above).

A rare complication of the nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor stavudine is HIV-associated neuromuscular weakness syndrome. Patients develop acute ascending weakness and respiratory failure over several days to weeks, with accompanying fatigue, abdominal pain, nausea, and vomiting. Weakness may be due to neuropathy, myopathy, or both. The clinical picture resembles Guillain-Barré syndrome, except for the accompanying systemic illness. Serum lactate is invariably elevated, and the mechanism is believed to be mitochondrial toxicity. Stavudine should be discontinued immediately and treatment is supportive. Prompt recognition in the early phase of this syndrome can result in marked improvement in the disorder which otherwise has high mortality.

62.7 General Issues

The optimal timing of initiating combination antiretroviral therapy has been an area of active research and ongoing debate. One issue is the possibility of worsening neurological outcome due to IRIS. Some argue that cART should be delayed until after specific antimicrobial treatment for opportunistic infections has obtained control of the infection, typically within 4-6 weeks. However, recent evidence suggests no difference if cART is started earlier. Although the evidence is mixed, a reasonable approach is to treat for any specific opportunistic infections for 2 weeks prior to initiating cART. For neurological infections, this primarily includes cryptococcal meningitis and toxoplasma encephalitis. Since PML and PCNSL have no effective specific antimicrobial therapy, cART should be initiated as soon as possible in these patients. An exception to this guideline is tuberculous involvement of the CNS, in which the risk for paradoxical worsening in the short term with cART is higher than for other opportunistic infections. For those with CD4 counts <100 cells/μl, cART should be started after 2 weeks of anti-Tb therapy. For those with higher CD4 counts (100-350 cells/μl), most recommend waiting until after the 2-month intensive phase of anti-Tb treatment before starting cART. For those with CD4 counts >350 cells/μl, cART may be delayed until Tb treatment is complete. For patients who develop CNS symptoms while on cART, this therapy should be continued and IRIS should be considered.

In addition to the neurological complications of HIV noted above, there are other important considerations in the neurological care of patients with HIV. Seizures are common in HIV, present in approximately 5-15% of HIV-positive patients. Conversely, patients with underlying seizure disorders – as from neurocysticercosis – may contract HIV. This poses particular challenges in treatment. Although data are limited, there does not appear to be any major effect of antiepileptic drugs (AEDs) on HIV or its course. AEDs, however, can have significant interactions with ART. Both the older AEDs (phenytoin, phenobarbital, carbamazepine, valproate) and certain antiretrovirals (protease inhibitors [PI’s] > non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors [NNRTIs] >> nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors [NRTIs]) are significantly protein-bound and metabolized by the hepatic cytochrome P450 system.

Hence, while NRTIs may be safely co-administered with older AEDs, the use of protease inhibitors and NNRTIs with older AEDs poses the risk of increased AED toxicity due to protein displacement and enzyme inhibition, as well as subtherapeutic ART levels due to enzyme induction by the AEDs. When available, newer AEDs with effectiveness for the clinical context should be used when patients are taking concurrent ART. Levetiracetam, which has effectiveness in both generalized and partial seizures and is not hepatically metabolized or significantly protein bound, is a particularly useful agent in this situation.

62.8 Key Concepts

HIV infection can affect every part of the nervous system from focal brain lesions to inflammatory myopathy. The most frequent HIV-related syndromes seen in the ICU setting are focal brain lesions, diffuse encephalitis, and meningitis. In many instances, the neurological syndromes can be the presenting manifestations of AIDS. The accompanying symptoms and signs of systemic illness, such as weight loss, oral thrush or other systemic opportunistic infections and unexplained lymphopenia on routine blood count, provide clues to the diagnosis. Based on the clinical presentation, radiographic findings, and serological and antigen testing, the diagnosis is usually possible without resorting to biopsy. In cases where the clinical context so allows, an empiric trial of treatment for toxoplasmosis is reasonable given the usually quick response to treatment. If there is no response, other entities must be considered and sought aggressively.

Patients with advanced HIV may have more than one process occurring simultaneously, and typical presenting symptoms and signs may be lacking given the lack of immune activation. Furthermore, patients with HIV are also susceptible to neurological infections which occur in the immunocompetent host, in particular tuberculosis, syphilis, and neurocysticercosis. Once diagnosis is made in an ART-naïve patient, specific antimicrobial agents should be initiated in advance of ART to help avoid IRIS. In treating patients with comorbid HIV and epilepsy, newer AEDs pose less risk of harmful drug interactions.

The pathophysiology, diagnosis, and treatment of HIV-associated neurological disease are complicated and evolving. In this context, the increasingly recognized role of immune reconstitution in neurological disease should be considered in unusual cases. Consultation with infectious disease experts when possible is helpful to address the unique aspects of neurological complications in the setting of HIV, but the neurological intensivist should maintain a working knowledge of the most common and most devastating neurological manifestations of HIV and their treatment.

General References

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree