Disorder |

Chromosome |

Recessive (R) or Dominant (D) |

Gene Product |

Special Features |

Motor Neuron Disease |

Spinal muscular atrophy |

|

SMA 1,2 |

5 |

(R) |

SMN and rarely NAIP protein in SMA 1,2,3 |

SMN protein mutation in 95% of Type 1,2,3 |

|

SMA 3 |

5 |

(R) and (D) |

|

SMA 4 (adult) |

Unknown |

(R) and (D) |

SMN defect in some |

Clinical overlap with progressive muscular atrophy |

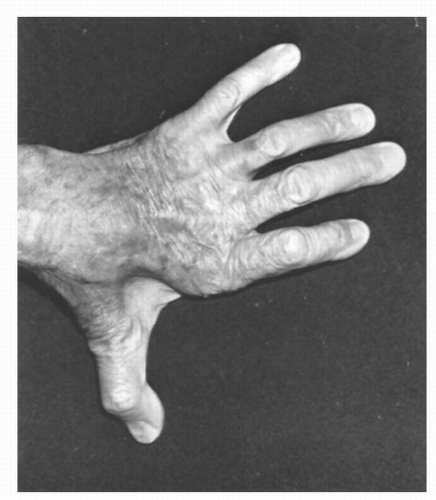

Spinal and bulbar muscular atrophy (Kennedy’s disease) |

X |

(R) |

Androgen receptor |

Androgen receptor gene enlarged (multiple CAG repeats) |

Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis |

|

Sporadic (90%-95%) |

No known defect |

None known |

See text |

|

Familial (5%-10%) |

|

|

SOD-1 mutation |

21 |

(D) |

More than 90 known mutations |

SOD-1 mutation in only 20% of familial cases |

|

|

Other mutations |

2,9, 15, 18 |

(D) or (R) |

Unknown |

Mutations very rare |

Peripheral Nerve (See Chapter 18 ) |

Neuromuscular Junction |

Acquired MG |

No gene defect |

— |

— |

— |

Congenital MG |

17 |

(R) |

Subunit of acetylcholine receptor protein |

No antibodies to the receptor protein, and immunosuppression is ineffective |

Muscular Dystrophies |

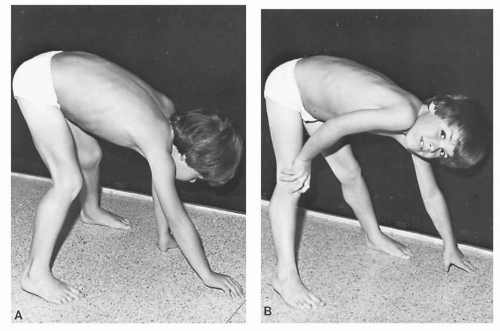

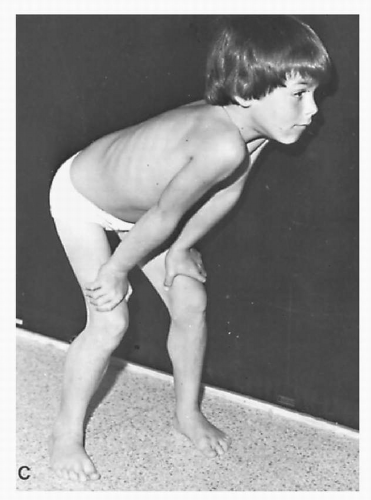

Duchenne/Becker dystrophy |

X |

(R) |

Dystrophin |

Gene deletion (60%-70%); point mutation in rest |

Facioscapulohumeral dystrophy |

4 |

(D) |

Unknown |

Specific deletions in 95% on chromosome 4, but gene itself is still unknown |

Limb-girdle dystrophy (recessive) |

2,4,5,13, 15, 17 |

(R) |

2A Calpain

2B Dysferlin |

LGMD2A mildly weak

LGMD2B proximal and distant weakness (Myoshi) |

LGMD 2A,2B,2C,2D,2E,2F,2G,2H,2E,2J |

|

|

2C, D, E, F sarcoglycan defect

2G Telethonin defect

2H E-3 Ubiquitin defect

21 Fukutin-related protein

2J Titan-related protein |

LGMD 2C-J tend to have severe symptoms, some resembling Duchenne dystrophy (see text) |

Limb-girdle dystrophy (dominant) |

|

LGMD1A |

5 |

(D) |

Myotilin |

Dysarthria seen |

|

LGMD1B |

3 |

(D) |

Caveolin |

“Rippling” muscle |

|

LGMD1C |

1 |

(D) |

Laminin |

Cardiac involvement |

Emery-Dreifuss muscular dystrophy |

X |

(R) |

Emerin |

Elbow contractures and cardiac changes |

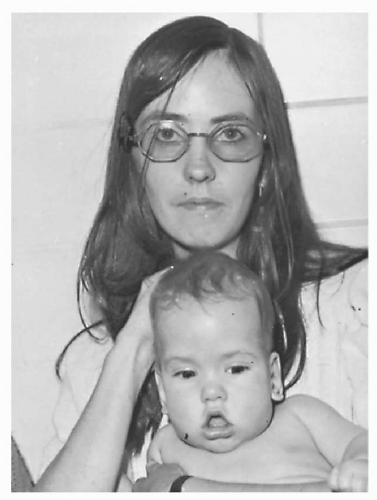

Congenital muscular dystrophy |

1,6 |

(R) |

Absent merosin in some |

Normal mentation |

9 |

(R) |

Fukutin defect |

Severe mental and developmental retardation |

Oculopharyngeal dystrophy |

14 |

(D) |

Protein regulates polyadeny-lation and mRNA size |

Ptosis, swallowing defects |

Myotonias |

Myotonia congenita |

7 |

(D) and (R) |

Muscle chloride channel |

Autosomal recessive form most common; dominant forms rare (Thomsen’s disease) |

Myotonic dystrophy (DM1) |

19 |

(D) |

Myotonin |

Gene has triplet (CCTG) repeats

Disease worse with increasing number of repeats |

Myotonic dystrophy (DM2 or PROMM) |

3 |

(D) |

An mRNA binding protein |

Gene has multiple CCTG repeats |

Inflammatory Myopathies |

Inclusion body myositis |

9 |

(R) |

Unknown |

Rare autosomal dominant form (most IBM is sporadic) |

Glycogen Storage Diseases |

Phosphorylase deficiency (McArdle’s) |

11 |

(R) and (D) |

Muscle phosphorylase |

Exercise intolerance, cramps |

Acid maltase deficiency |

17 |

(R) |

Acid maltase |

Fatal in infants; moderately severe in adults |

PFK deficiency |

1 |

(R) |

Phosphofructokinase |

Exercise intolerance |

PGAM-M deficiency |

7 |

(R) |

Phosphoglycerate mutase |

Exercise intolerance |

PGK deficiency |

X |

(R) |

Phosphoglycerate kinase |

Myopathy rare |

LDH deficiency |

11 |

(R) |

Lactic dehydrogenase |

Myopathy rare |

Debranching enzyme deficiency |

21 |

(R) |

Debranching enzyme |

Survival to adulthood common |

Branching enzyme deficiency |

3 |

(R) |

Branching enzyme |

Early death common |

Phosphorylase b kinase deficiency |

X, 16,7,6 |

(R) |

Phosphorylase b kinase |

Fatal in infancy, moderately severe in adults |

Lipid Storage Disorders |

CPT II deficiency |

1 |

(R) |

Carnitine palmitoyl transferase 11 |

Diagnosis by muscle biopsy and CPT enzyme assay |

Carnitine deficiency |

Unknown |

(R) |

Unknown |

Diagnosis by muscle biopsy and muscle carnitine assay |

Mitochondrial Myopathies |

Kearns-Sayres syndrome (KSS) |

Mitochondrial DNA |

Maternal inheritance |

Various mitochondrial proteins |

Extraocular muscle paresis, cardiac conduction block |

MELAS |

“ |

“ |

tRNA |

Lactic acidosis, stroke |

MERRF |

“ |

“ |

tRNA |

Myoclonus epilepsy, ataxia

Diagnosis by distinctive muscle biopsy changes |

Congenital Myopathies |

Myotubular myopathy |

|

Neonatal, late infantile, adult-onset forms |

X in some |

(R) and (D) |

Myotubularin in neonatal form |

Neonatal often fatal |

|

Unknown |

(R) and (D) |

Unknown in adult form |

Central core disease |

19 |

(D) |

Ryanodine receptor |

Same gene as for malignant hyperthermia |

Nemaline myopathy |

1,2,19 |

(R) and (D) |

Mutations reported in nebulin, alpha actin, alpha and beta tropomyosin, troponin |

Respiratory problems common |

Channelopathies |

Hypokalemic periodic paralysis |

1 |

(D) |

Muscle calcium channel |

Diaphragm never involved |

Hyperkalemic periodic paralysis/paramyotonia congenital/potassium aggravated myotonia |

17 |

(D) |

Muscle sodium channel |

Different mutations of sodium channel gene define unique clinical features of each |

SMA, spinal muscular atrophy; SMN, survival motor neuron; NAIR neuronal apoptotic inhibitory protein; CAG, cytosine-adenine-guanine; SOD, superoxide dismutase; MG, myasthenia gravis; LGMD, limb-girdle muscular dystrophy; mRNA, messenger ribonucleic acid; CTG, cytosine-thymine-guanine; DM, myotonic dystrophy; PROMM, proximal myotonic myopathy; PFK, phosphofructo kinase; PGAM-M, phosphoglycerate mutase; PGK, phosphoglycerate kinase; LDH, lactic dehydrogenase; CPT, carnitine palmitoyl transferase; MELAS, mitochondrial myopathy, encephalopathy, lactacidosis. stroke; tRNA, transfer RNA; MERFF, myoclonus epilepsy with ragged-red fibers. |

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access