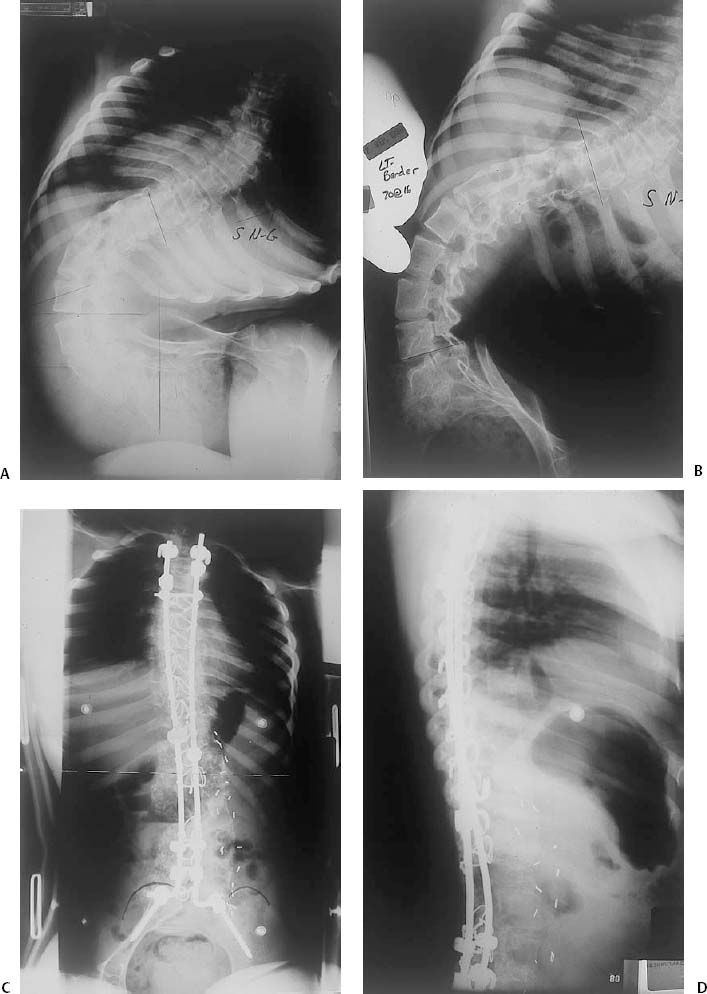

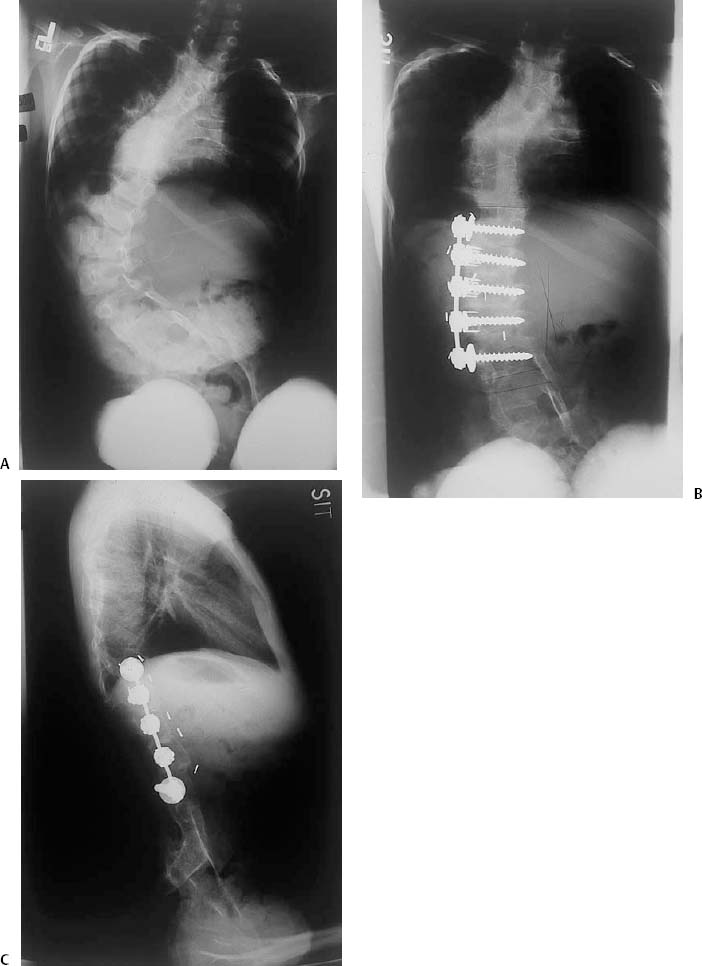

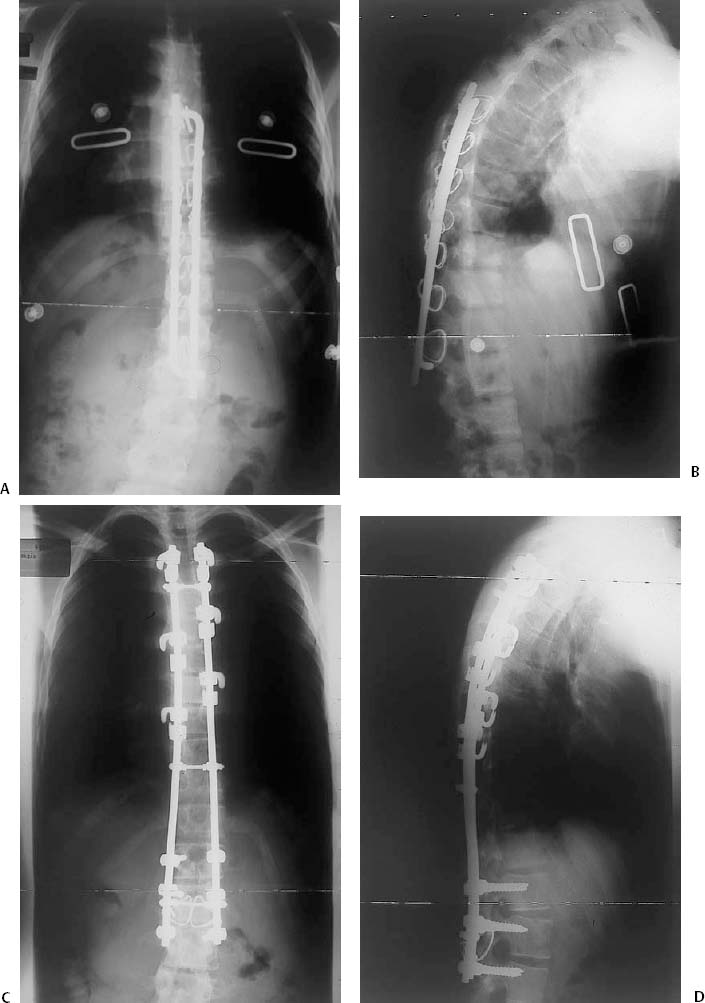

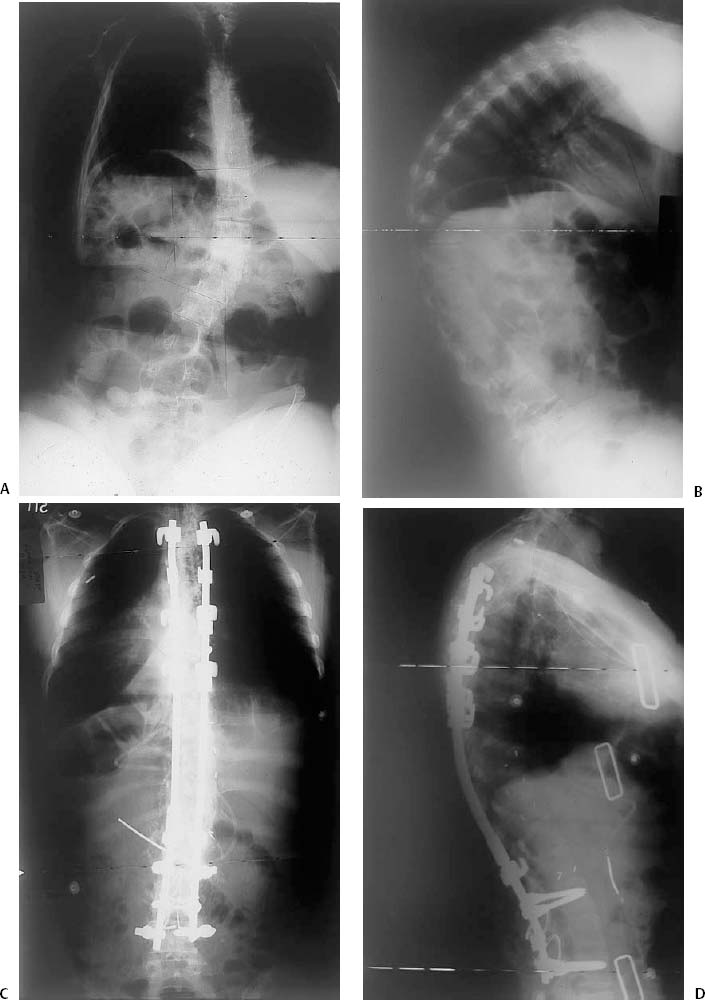

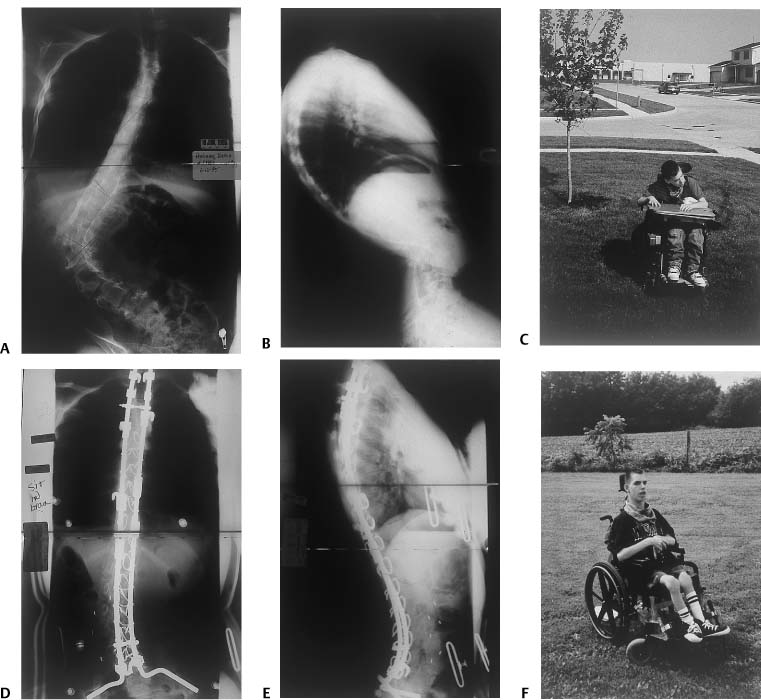

Chapter 14 This chapter will summarize the collective and traditional wisdom about neuromuscular spine deformity in general and address a few specific conditions to illustrate the concepts and difficulties in reaching the treatment goals of this condition. The literature on this topic is very extensive. The reference section of this chapter lists many book chapters from recently published texts that are quite complete and informative, written by experts in this area of spinal deformity. Additionally, these references have extensive bibliographies that provide the reader with an ample opportunity to peruse the many additional articles that address and expand on the comments in this chapter. Neuromuscular deformities, also called paralytic spinal deformities, are associated with some type of underlying neurologic condition and may be just one of several musculoskeletal abnormalities caused or exacerbated by the neurologic disease. The neurologic condition may be the patient’s primary diagnosis or may be part of a larger syndrome. Although spinal deformity is a consequence of these diagnoses and it is much more prevalent than in the general population, rarely, if ever, is the prevalence 100% within those diagnoses, and the behavior of the deformity and its severity may vary greatly among those affected.1–3 The etiology of neuromuscular deformity is primarily that of muscular weakness and/or imbalance and control that affects trunk alignment. Thus, patients with flaccid muscles (e.g., Duchenne’s muscular dystrophy, polio)4–6 (Fig. 14–1), as well as those with spasticity (e.g., cerebral palsy)7 or those with involuntary muscle contraction (e.g., dystonia and Friedreich’s ataxia),8 can develop deformity. The severity of the underlying muscle abnormality, patient age (e.g., skeletal maturation status), general health, and the natural history of the underlying diagnosis all affect the deformity behavior. Additionally, comorbidities associated with the underlying diagnosis (e.g., lung function, recurrent uri-nary tract infections, cardiomyopathy, etc.)5,9,10 may influence how the deformity is handled. Some syndromes have associated spinal deformities, which are particularly “malignant” in their severity and progression as well as their “refractoriness” to even surgical treatment (e.g., familial dysautonomia). Other types are affected not only by the muscular weakness but also abnormalities of the vertebrae (e.g., myelomeningocele) (Fig. 14–2). Patients who have suffered a spinal cord injury secondary to spinal fracture and/or dislocation frequently have had surgical treatment for it. They can develop subsequent spinal deformity from failure of the initial injury procedure as well as the superimposed paralytic factors11 (Fig. 14–3). Sometimes the major deformity is in the sagittal plane without any scoliosis (coronal plane) (Fig. 14–4). Neuromuscular curves frequently present to the spine surgeon only after they have progressed to large magnitude. Although large idiopathic curves in adolescence are generally not painful and do not interfere with activities of daily living, severe neuromuscular curves frequently cause impaired posture and discomfort that interfere with basic functions such as sitting (Fig. 14–5). Therefore, there is clear evidence of how neuromuscular deformities affect the patient functionally. Though most authors who have written about neuro-muscular spinal deformity suggest that treated patients benefit physically, functionally, and emotionally (and so do their caregivers)12,13 at least one article refutes this notion.14 Neuromuscular deformity may be classified broadly into two types: the developmental and the acquired. The developmental type of neuromuscular scoliosis would be associated with conditions that are recognized at birth or soon thereafter, and examples of such conditions would be cellular abnormalities, inherited myopathies, myelomeningocele, and cerebral palsy. The other type could be considered as acquired, and examples of underlying conditions causing acquired deformity would be spinal cord injury, transverse myelitis, and polio. However, deformity in either type has the potential for severe progression because most deformity starts while the patients are skeletally immature. Even in those diseases with a fairly limited life expectancy, curve progression may occur early, and to improve the quality of life, early treatment may be necessary. For some of these conditions, treatment of the spinal deformity may in fact alter the natural history of the underlying condition because things such as decreased pulmonary function may improve with correction of a severe deformity. Also, treatment of the underlying neurologic condition may actually have a profound effect on behavior and natural history of the spinal deformity; examples of this would be decompression of a Chiari malformation or the treatment of Duchenne’s muscular dystrophy with steroids. Figure 14–1 This teenage girl had polio with the extensor hallucis longus on one foot as the only functioning lower extremity muscle. She developed a severe spinal deformity with 90 degrees of pelvic obliquity: (A) anterior/posterior (AP) and (B) bender thoracolumbar (TL) radio-graphs. A two-stage reconstruction was done involving a two-level vertebrectomy, anterior spinal fusion (ASF), posterior spinal fusion (PSF), and instrumentation to the pelvis with excellent correction: (C) AP and (D) lateral post-op radiographs. A positive Ober test on the left was noted post-op. After an Ober-Yount release, she was fitted for hip-knee-ankle-foot orthosis (HKAFO) and was able to ambulate with a walker. Figure 14–2 This young girl has myelomeningocele with spotty lower extremity motor function and several neuraxis abnormalities as well as a complex spinal deformity but no sagittal plane malalignment: (A) pre-op AP radiograph. ASF with instrumentation alone provided nice correction: (B) AP and (C) lateral post-op radiographs. No neurosurgical intervention was involved, and pre-op neurological function was preserved. Figure 14–3 This adolescent male had a spinal injury associated with an incomplete spinal cord injury. Surgical treatment of the initial injury was performed but failed: (A) AP and (B) lateral radiographs. Revision of the spinal surgery resulted in normalization of spinal alignment and a solid fusion: (C) AP and (D) lateral post-op radiographs. Figure 14–4 This older teenage girl with Rett syndrome has a severe kyphosis as her main deformity. (A) AP and (B) lateral pre-op radiographs. She had a two-stage reconstruction with a period of halo-gravity traction between the anterior and posterior procedures. Excellent correction and balance were achieved: (C) AP and (D) lateral post-op radiographs. Figure 14–5 This nonambulatory teenager with cerebral palsy developed a significant deformity [(A) AP and (B) lateral pre-op radiographs] associated with difficulty sitting (C). A same-day ASF and PSF. with instrumentation to the pelvis achieved nice correction [(D) AP and (E) lateral post-op radiographs], and sitting was markedly improved (F). Because the deformity can occur in the very young, curve control without resorting to definitive spinal fusion and the subsequent trunk shortening that would occur with such treatment would be desirable. Therefore, young children are often offered brace treatment until the spine has a chance to grow. However, it does not appear that braces affect the natural history of these curves. Braces can improve trunk alignment and make sitting better and more comfortable. However, in order for that to happen, the child must be relatively thin (at least not terribly obese) so that the brace actually fits well. Additionally, the curve needs to be flexible so that passive correction can occur and leveling of the pelvis can occur, otherwise the brace provides absolutely no benefit. “Successful bracing” is continued until age 10 or 11, at which time definitive fusion can be performed without as much trunk shortening as would have occurred with fusion at an earlier age. When braces are used, they should only be used when the patients are up and about, and not be worn at nighttime. Contraindications to bracing are stiff curves with pelvic obliquity, very obese patients whom the brace does not fit properly, and those with an unreliable family situation in which compliance would be a problem.1–3 Curves of large magnitude with pelvic obliquity require surgery for proper and permanent correction of trunk malalignment and leveling of the pelvis. In fact, the goals of surgical treatment are the following: correction of the curve in the coronal plane, normalization of sagittal alignment, leveling of the pelvis, and the achievement of a solid fusion (if in fact the surgical treatment being performed is a definitive fusion)1–3(Fig. 14–6). Traditionally definitive treatment means a long posterior spinal fusion to the pelvis (with possibly an anterior supplemental fusion) and posterior instrumentation. However, today there are alternatives to this approach. In certain situations, only a short anterior spinal fusion with instrumentation may be indicated, especially in patients who are less involved neurologically, are walkers, and who have lumbar or thoracolumbar curves. Though this technique does involve a spinal fusion, its effect on trunk height is less than would occur with a long posterior fusion because many fewer vertebrae are involved in the fusion segment15(Figs. 14–7 and 14.8). There are some new techniques that fall into the category of “fusionless” spinal correction, and these would include such things as “growing rods,” vertebral stapling, and VEPTR (vertical expandable prosthetic titanium rib). Whether stapling will prove to be a permanent and final procedure or whether for a given patient treatment will need to be finished off by converting the stapled spine to a spinal fusion will need to be determined on an individual basis.16

Neuromuscular Scoliosis

♦ Classification

♦ Nonoperative Treatment

♦ Surgical Treatment

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree