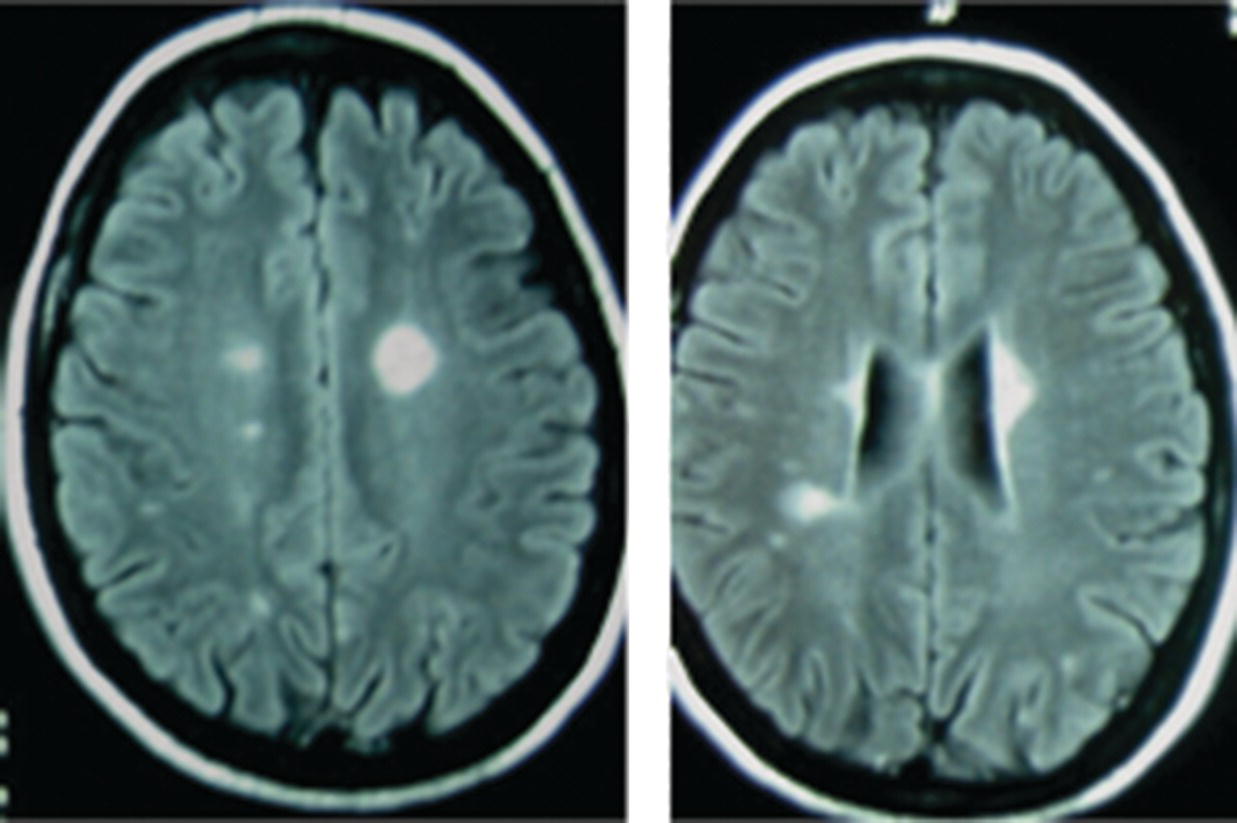

16 Thomas F. Scott Department of Neurology, Drexel University College of Medicine, Pittsburgh, PA, USA Allegheny MS Treatment Center, Pittsburgh, PA, USA Neurosarcoidosis (NS) is a rare and enigmatic disorder, essentially idiopathic. The primary substrate or mechanism of multiple organ tissue destruction appears to be a granulomatous inflammatory process. Although new knowledge of the immunopathology is slowly emerging as in other idiopathic inflammatory disorders, NS and even the more common pulmonary or systemic sarcoidosis remain largely mysterious. At present, a genetic predisposition is suggested by familial studies, and environmental triggers are postulated, but we are left with little in the realm of solid scientific evidence to explain the etiology of sarcoidosis. This summary of the clinical aspects of NS is divided into general principles of diagnosis, treatment, and prognosis, followed by discussions of clinical challenges in treating NS as it typically presents in various anatomical regions in the central and peripheral nervous system. NS is sometimes used as the prototypic example of a zebra; clinicians should avoid thinking about until all the horses have been rounded up for elimination. The consideration of NS usually is appropriately placed near the end of the list of possibilities when encountering a patient with one of the typical presentations (e.g., subacute myelopathy, CPA tumor, peripheral neuropathy (PN), isolated cranial neuropathy). Roughly half of NS is diagnosed prior to any knowledge of systemic sarcoidosis. A large proportion of patients presenting initially with neurological symptoms due to NS will have systemic sarcoidosis diagnosed as part of the workup for their neurological complaints. A consideration of NS should alert physicians to review a patient’s medical history for systemic evidence of diagnosis (dry cough, skin lesions, other organ involvement). Biopsy of non-CNS tissues is often possible and generally preferred to biopsy of nervous tissue. Applying the widely used Zajicek criteria, or similar criteria, the term definite NS is reserved for patients who have undergone biopsy of nervous tissue found to have granulomatous inflammatory pathology. Many or most patients are ultimately classed as only probable NS, after obtaining evidence of granulomatous inflammatory in non-nervous system tissue, and empirical treatment is undertaken rather than risking biopsy of CNS tissue. A minority of cases in large series met criteria for definite NS. The physician’s tools for arriving at a diagnosis of NS include a standard array of history taking and physical examination skills combined with targeted laboratory testing, essentially unchanged over the last two decades. Concerning all the various presentations of NS, the diagnosis is obviously much easier when a diagnosis of systemic sarcoidosis has already been established by tissue biopsy. If radiographic and other paraclinical evidence for NS is accompanied by typical clinical manifestations, a biopsy of the nervous tissue can generally be avoided in patients with well-established systemic disease. Given a lack of any such history, a search for evidence of systemic disease is undertaken as soon as NS is suspected. History taking and review of systems should include particular attention to stigmata of systemic sarcoidosis, and physical examination should include a skin examination. Initial laboratory studies, including imaging, are directed according to clinical localization of lesions (e.g., electromyography and nerve conduction studies for peripheral NS, cerebral or spinal MRI for central nervous system sarcoidosis; see Table 16.1). Initial studies also include a search for asymptomatic disease (e.g., CT of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis) (Figure 16.1). Table 16.1 Selected Differential Diagnosis for NS According to Localization Figure 16.1 Algorithm for diagnosis of neurosarcoidosis. The tendency for an initial misdiagnosis of NS as multiple sclerosis (MS) has been discussed in many reports, involving 8 out of 50 patients in one large series of NS (see Figure 16.2 for a representative case). Many of these patients present with acute or subacute complaints related to optic neuropathy or myelopathy, clinically indistinguishable from a clinically isolated syndrome due to MS, and with evidence of systemic sarcoidosis emerging only years later. Combining the clinical picture with the typical laboratory findings of NS, namely, rounded deep white matter lesions often seen on MRI, and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) with immune activation, we see that NS can be the ultimate mimic for MS (for detailed description of CSF abnormalities, see succeeding text). Thus far, there has not been a detailed biopsy or autopsy description of a patient with both diseases simultaneously, although there have been descriptions of tissue studies of deep white matter lesions in NS being pathologically distinct from MS. Figure 16.2 FLAIR MRI of a patient initially diagnosed as MS with a history of steroid-responsive optic neuritis in 1989 followed 2 years later by a right internuclear ophthalmoplegia. The patient developed biopsy-proven pulmonary sarcoidosis 6 years after her optic neuritis and stopped beta-interferons at that time due to a strong suspicion of NS. The patient was then followed long term for a total of 19 years from onset without further relapse or change in MRI. Corticosteroids and alternative immunosuppressant agents constitute the mainstay of treatment for most cases. Treatments are aimed at either quickly reducing inflammation-mediated injury to the nervous system or relieving mass effect caused by granulomatous tissue surgically. Initial stabilization is followed usually by an empiric attempt to prevent relapse by slowly withdrawing immunologically active agents over months or years. One exceptional situation in which urgent evaluation for possible lifesaving surgery is required can be seen in patients who develop hydrocephalus (either communicating or noncommunicating). Due to the rarity of NS, there have been no randomized controlled comparative studies of any treatments (no class I or class II evidence is available). The readily apparent response to steroids in most cases combined with the seriousness of potential neurological deficits occurring in NS makes standard placebo trials impractical in the acute setting. It is foreseeable that a multicenter trial might be able to compare different treatment regimens involving steroids plus other agents in NS during long-term care (perhaps following patients for many months or years). Two basic treatment strategies have emerged from small and large case series of treated patients: (1) initial treatment with corticosteroids (moderate- or high-dose regimens), weaning over weeks or months and reserving alternative therapies for relapsing or refractory cases. (2) Initial treatment may be tailored to the severity of the initial presentation (e.g., using alternative immunosuppressive agents up front in conjunction with corticosteroids in patients with symptomatic intracranial or spinal NS and using corticosteroid steroids alone in patients with mild isolated cranial nerve disorders or PN). Small case series expound the virtues of stepwise treatments moving toward more novel treatments in refractory cases, with some patients requiring three or more attempts to arrive at a regimen resulting in disease control. There are rare reports of low-dose radiation therapy allowing preservation of optic nerve function in refractory disease. If relapse occurs, which is often years after initial control, it is reasonable to return to previously used medications to induce another remission (Table 16.2). Table 16.2 Reported Treatments Optimal dosages are not determined (refer to specific recommendations of the limited studies available for each medication, but typical dosages for Cytoxan might involve monthly pulses at 700 mg/m2 for 6 months, methotrexate 10–20 mg once weekly for several months, mycophenolate 1000 mg bid for several months, and azathioprine 2–2.5 mg/kg for several months. Note that since these immunosuppressants all have serious toxicity profiles, they should only be prescribed by experienced physicians who have special expertise in neuroimmune disorders. CSF analysis is often part of the workup for suspected NS, for example, as part of the workup for cranial neuropathy, yielding the designation of aseptic meningitis, as the investigative process evolves. In fact, most neurologic presentations for sarcoidosis might be expected to justify consideration of CSF analysis. The aseptic meningitis picture of NS is typically seen with a CSF formula of mild to moderately elevated white blood cells, usually lymphocyte predominant. Other typical CSF findings may sometimes help differentiate NS from MS, although considerable overlap exists (see Table 16.3). When NS meningitis is seen in association with headaches or other symptoms of increased intracranial pressure, physicians should consider the possibility of evolving hydrocephalus, a rare but life-threatening complication. Frequent imaging and CSF analysis in these patients are suggested. Unfortunately, we have had experience with a few cases of extreme increased intracranial pressure leading to death in the setting of only minimal or no signs of hydrocephalus radiographically, making management in these cases difficult. Extremely high CSF protein levels may be a clue in identifying life-threatening aseptic meningitis. On the other hand, many cases of aseptic meningitis due to NS seem to be easily managed with only moderate doses of corticosteroids. Therefore, in a relatively uncomplicated setting, we generally treat aseptic meningitis with corticosteroids alone. Table 16.3 CSF in NS versus MS Myelopathy due to NS usually presents as a subacute process with subtle symptoms and examination findings evolving over months (spastic weakness, sensory complaints). The diagnosis is often made in the setting of known systemic disease, typically with nonspecific intramedullary abnormalities seen on MRI, which may or may not enhance. MRI lesions may be small or span multiple segments. In the absence of systemic disease, biopsy is often undertaken to make a diagnosis, especially if the lesion radiologically mimics a neoplasm with enhancement and expansion of the spinal cord. MS is not suspected when prominent nerve root enhancement and meningeal enhancement are seen. Myelopathy can occasionally be related to compression from extra-axial lesions of sarcoidosis involving paraspinal tissues or bone. More subtle presentations can easily be mistaken for a form of MS (often primary progressive) or a clinically isolated syndrome, especially in the setting of nonspecific MRI findings and spinal fluid abnormalities (e.g., oligoclonal bands, increased IgG concentration). A moderately elevated CSF leukocyte count, low CSF glucose, and very high CSF may all point away from a diagnosis of MS (see Table 16.3). Alternatively, spinal fluid may be normal. Intra-axial lesions of NS mimic a wide variety of disorders. Multifocal intracranial lesions might present with headache, seizures, encephalopathy, ataxia, or focal signs and symptoms. Lesions may be seen on MRI as subtle and nonspecific abnormalities of cerebral white matter or very rounded and ovoid Dawson’s fingers, mimicking MS. Rarely, deep white matter lesions are seen in the setting of vasculitis related to sarcoidosis. Deep enhancing or nonenhancing lesions of the brainstem and diencephalon may mimic lymphoma, MS, histiocytosis, or glioma. Occasionally, large parenchymal lesions can mimic glioblastoma. A search for systemic disease is often negative, leading to diagnostic biopsy. In some cases of NS presenting with clinical, MRI, and CSF findings all consistent with NS, a diagnosis of MS is given but changed years later after systemic disease becomes apparent. Very high CSF leukocyte counts and protein levels are among the red flags that should point clinicians away from MS. Several reports of parenchymal cerebral hemorrhages, including severe brainstem hemorrhages, have called attention to the tendency of the granulomatous inflammation of NS to invade and disrupt small blood vessels. Ischemic strokes are also rarely seen, sometimes in the setting of widespread intracranial leptomeningeal inflammation. Reports of both intracerebral hemorrhage and ischemic stroke are among the rarest available, making up only 0–2% of patients in large series.

Neurosarcoidosis

Introduction

General principles of diagnosis

General principles of treatment

Dosages

Specific presentations

Aseptic meningitis

Test

NS

MS

Oligoclonal bands, high IgG concentration

Often

Often

Polymorphonuclear cells, eosinophils

Often

None

Lymphocytosis

May be mild or moderate

Mild

Glucose

Sometimes low

Normal

Total protein

Occasionally very high

Normal or mild increase

Myelopathy

Cerebral neurosarcoidosis

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree