Non-Depot Antipsychotic Drugs

Use of antipsychotic drugs

Antipsychotic drugs (also known as ‘neuroleptics’) have a wide variety of uses in psychiatric practice. The main uses of antipsychotic drugs include the treatment of:

schizophrenia

bipolar mood disorder—including the acute treatment of mania, hypomania and depression

severe depression with psychotic features

psychosis associated with delirium, dementia, or other organic disorders

psychosis caused by other drugs and by psychoactive substance abuse

delusional disorders

symptomatic treatment in disorders such as Huntington’s disease

in the short-term management of violent behaviour.

There are also several non-psychotic uses for antipsychotic drugs, which should be borne in mind when seeing patients. For example, in dermatological practice, ‘off-label’ prescribing of antipsychotic drugs sometimes occurs for conditions such as pruritus, neurotic excoriations and pathological skin picking, trichotillomania, and cutaneous pain syndromes (including postherpetic neuralgia) (Koo & Ng, 2002).

Classification of first-generation antipsychotic drugs

In general, the older, first-generation, or typical, antipsychotic drugs exhibit antagonistic activity at brain dopaminergic D2 receptors. The main groups are as follows.

Phenothiazines

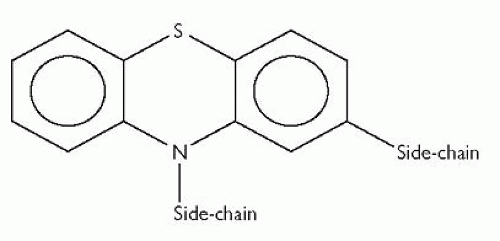

Phenothiazines have a central tricyclic structure made up of 2 benzene rings covalently bounded to each other through 1 sulphur- and 1 nitrogenbridge, as shown in Fig. 3.1.

There are 3 main groups of phenothiazine antipsychotic drugs:

Those with aliphatic side-chain attached to the nitrogen-bridge, e.g. chlorpromazine, levomepromazine, and promazine. The antipsychotic drugs in this subgroup tend to have a relatively low potency (though they are certainly clinically effective).

Those with a piperidine ring in the side-chain attached to the phenothiazine nitrogen-bridge, e.g. pipotiazine and pericyazine. These antipsychotic drugs tend to have a depressant action on cardiac conduction and repolarization.

Those with a piperazine group attached to the nitrogen-bridge, e.g. fluphenazine, trifluoperazine, perphenazine and prochlorperazine.

Table 3.1 shows the general degree of sedative actions and antimuscarinic and extrapyramidal side-effects of these 3 subgroups. The remaining groups of first-generation antipsychotic drugs are listed here tend to resemble phenothiazines with piperazine side-chains in these respects.

Thioxanthenes

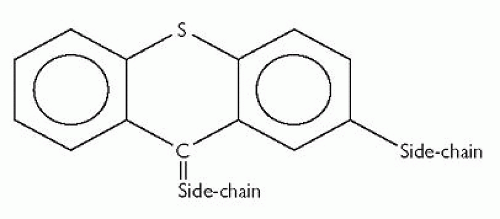

Like phenothiazines, thioxanthenes are also tricyclic antipsychotic drugs. The core tricyclic structure is similar to that of the phenothiazines, but with a carbon-bridge rather than a nitrogen-bridge, as shown in Fig. 3.2. Again, two side-chains are attached to this tricyclic structure.

Examples of thioxanthenes include flupentixol and zuclopenthixol, which are both available as depot preparations.

Table 3.1 The general degree of sedative actions and antimuscarinic and extrapyramidal side-effects of the 3 subgroups of phenothiazines | ||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Butyrophenones

The butyrophenones are phenylbutylpiperidines and include haloperidol and benperidol.

Diphenylbutylpiperidines

The main diphenylbutylpiperidine in clinical psychiatric use in the UK at the time of writing is pimozide. (Others include fluspirilene and penfluridol.)

Substituted benzamides

The main substituted benzamide used as an antipsychotic drug in the UK and many other countries is sulpiride. Some authorities class sulpiride as an atypical antipsychotic drug. Other substituted benzamides include metoclopramide, which is used as an antiemetic drug and which may cause extrapyramidal side-effects, hyperprolactinaemia, tardive dyskinesia, and other side-effects associated with the use of typical antipsychotic drugs. A molecular variant of sulpiride, amisulpride, is also used as an antipsychotic drug, and is a second-generation (or atypical) antipsychotic which is considered in the next section.

Second-generation antipsychotic drugs

In general, the newer, second-generation, or atypical, antipsychotic drugs are associated with less frequent extrapyramidal side-effects than the firstgeneration antipsychotics. The second-generation antipsychotic drugs currently in routine use in the UK are:

amisulpride

aripiprazole

clozapine

olanzapine

paliperidone

quetiapine

risperidone.

Clozapine is a dibenzodiazepine and is the archetypal atypical antipsychotic; olanzapine and quetiapine have similar molecular structures. Aripiprazole is a quinolinone derivative while risperidone is a benzisoxazole and paliperidone is an active metabolite of risperidone (paliperidone is 9-hydroxyrisperidone).

NICE guidance

In 2009, the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence, known as NICE, which is an independent UK organization responsible for providing national guidance on the promotion of good health and the prevention and treatment of ill health, issued the following guidance on pharmacological interventions for patients suffering from schizophrenia.

‘For people with newly diagnosed schizophrenia, offer oral antipsychotic medication. Provide information and discuss the benefits and side-effect profile of each drug with the service user. The choice of drug should be made by the service user and healthcare professional together, considering:

the relative potential of individual antipsychotic drugs to cause extrapyramidal side effects (including akathisia), metabolic side effects (including weight gain) and other side effects (including unpleasant subjective experiences)

the views of the carer if the service user agrees.’

Before starting antipsychotic medication, NICE recommend that an electrocardiogram should be carried out if any of the following criteria is met:

This investigation is specified in the manufacturer’s summary of product characteristics.

A physical examination has identified specific cardiovascular risk (such as hypertension).

There is a personal history of cardiovascular disease.

The patient is being admitted as an inpatient.

CATIE and CUtLASS

CATIE and CUtLASS refer to two large studies comparing first-generation antipsychotics with second-generation antipsychotics; both studies were funded independently of pharmaceutical companies. CATIE (Clinical Antipsychotic Trials of Intervention Effectiveness) was funded by the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) and compared the second-generation antipsychotics olanzapine, quetiapine, risperidone and ziprasidone (included in the study after its approval by the US Food and Drug Administration) and the first-generation antipsychotic perphenazine. Almost 1500 patients with chronic schizophrenia were randomly assigned to treatment with one of these antipsychotic drugs in a double-blind design, with the primary outcome measure being discontinuation of treatment for any cause (Lieberman et al., 2005). The surprising conclusions of this study were as follows: ‘The majority of patients in each group discontinued their assigned treatment owing to inefficacy or intolerable side effects or for other reasons. Olanzapine was the most effective in terms of the rates of discontinuation, and the efficacy of the conventional antipsychotic agent perphenazine appeared similar to that of quetiapine, risperidone, and ziprasidone. Olanzapine was associated with greater weight gain and increases in measures of glucose and lipid metabolism.’

CUtLASS (Cost Utility of the Latest Antipsychotic drugs in Schizophrenia Study) was funded by the Health Technology Assessment Programme and compared first-generation antipsychotics and second-generation antipsychotics (apart from clozapine). 227 patients with schizophrenia and related disorders were assessed for medication review because of inadequate response or adverse effects; the patients were randomly prescribed either first-generation antipsychotics or second-generation antipsychotics (other than clozapine), with the individual medication choice in each arm being made by the patients’ psychiatrists (Jones et al., 2006). The study found that patients in the first-generation antipsychotic arm showed a trend toward greater improvement in Quality of Life Scale and symptom scores, and overall patients reported no clear preference for either group of antipsychotics. The authors concluded that: ‘In people with schizophrenia whose medication is changed for clinical reasons, there is no disadvantage across 1 year in terms of quality of life, symptoms, or associated costs of care in using [first-generation antipsychotics] rather than nonclozapine [second-generation antipsychotics]. Neither inadequate power nor patterns of drug discontinuation accounted for the result.’

Owens (2011) has recently commented as follows on the implications of these two major studies: ‘Antipsychotic choices should be based on an ‘individual risk:benefit appraisal’, where the particular illness, then the individual patient and finally individual drug variables are considered in turn for treatment that is truly ‘tailored’. Now, the entire repertoire of antipsychotics can be opened up to equal consideration.

Alas, a whole generation has matured through the specialist ranks with little or no exposure to older antipsychotics. For them, Stelazine [trifluoperazine] might as well be a fizzy drink! A major educational undertaking is necessary.’

Equivalent doses

Equivalent doses for a selection of orally administered antipsychotic drugs are given in the British National Formulary, 62nd edition, and reproduced in Table 3.2. They are intended only as an approximate guide. Note that these equivalent doses should not be extrapolated beyond the maximum dose for each antipsychotic drug.

Table 3.2 Equivalent doses of oral antipsychotics. Reproduced with permission from the British National Formulary, 62nd edn. BMJ Group & Pharmaceutical Press, London | ||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

High doses

In the UK, antipsychotic doses which exceed those given in the latest British National Formulary are unlicensed. The Royal College of Psychiatrists have issued the following advice on doses exceeding the British National Formulary upper limits.

Consider alternative approaches including adjuvant therapy and newer or second-generation antipsychotics such as clozapine.

Bear in mind risk factors, including obesity; particular caution is indicated in older patients, especially those over 70.

Consider potential for drug interactions.

Carry out ECG to exclude untoward abnormalities such as prolonged QT interval; repeat ECG periodically and reduce dose if prolonged QT interval or other adverse abnormality develops.

Increase dose slowly and not more often than once weekly.

Carry out regular pulse, blood pressure, and temperature checks; ensure that patient maintains adequate fluid intake.

Consider high-dose therapy to be for limited period and review regularly; abandon if no improvement after 3 months (return to standard dosage).

In addition, the British National Formulary offers the following advice:

‘Important: When prescribing an antipsychotic for administration on an emergency basis, the intramuscular dose should be lower than the corresponding oral dose (owing to absence of first-pass effect), particularly if the patient is very active (increased blood flow to muscle considerably increases the rate of absorption). The prescription should specify the dose for each route and should not imply that the same dose can be given by mouth or by intramuscular injection. The dose of antipsychotic for emergency use should be reviewed at least daily.’

Overall cautions and contraindications

Caution

Caution should be exercised when considering prescribing antipsychotic drugs to patients suffering from:

A propensity to angle-closure glaucoma (including a family history).

Blood dyscrasias—an urgent blood count should be carried out if a patient being treated with an antipsychotic drug develops an unexplained infection, pyrexia, or malaise; blood dyscrasias can be of rapid onset.

Cardiovascular disease—many antipsychotic drugs affect the heart (and may prolong the cardiac rate-corrected QT interval, QTc) and blood vasculature directly, while some, such as chlorpromazine, olanzapine and risperidone, can induce orthostatic hypotension.

Depression.

Epilepsy (including disorders predisposing to epilepsy)—the seizure threshold is lowered by many antipsychotic drugs and electroencephalographic discharge patterns may occur. It is best not to use antipsychotic drugs, if at all possible, in patients who are withdrawing from alcohol or other drugs that cause central nervous system depression, such as barbiturates and benzodiazepines.

Jaundice (including a history of this)—jaundice (usually without pruritus) may particularly occur with chlorpromazine treatment.

Myasthenia gravis.

Old age—the elderly are particularly susceptible to postural hypotension. Many antipsychotic drugs have a poikilothermic effect, which is probably mediated by hypothalamic actions, such that shivering is inhibited, so reducing the ability of the body to warm up in the cold. The elderly may suffer from hypothermia when it is cold and from hyperthermia when it is very warm.

Parkinson’s disease—many antipsychotic drugs act as dopaminergic antagonists and such action in the basal ganglia can exacerbate pre-existing Parkinson’s disease, as well as inducing extrapyramidal effects in patients who do not suffer from this disease.

Prostatic hypertrophy—in men with this condition, antipsychotic drugs may cause acute urinary retention.

Renal impairment.

Respiratory disease, severe. (Note that if a patient—with or without a history of respiratory disease—appears suddenly to have developed an apparent respiratory infection, the possibility of the development of a blood dyscrasia should be considered and an urgent blood count carried out, as mentioned earlier in this list.)

Activities to avoid

The following should be avoided if at all possible:

Breastfeeding—mothers should not breastfeed while taking antipsychotic drugs as the latter tend to be present in the milk.

Driving—antipsychotic treatment may be associated with drowsiness, which can clearly be dangerous during driving. Note that antipsychotics can also increase the effects of alcohol.

Exposure to ultraviolet light—many antipsychotic drugs may cause photosensitization, so that exposure to sunlight and other sources of ultraviolet light (such as sun tanning equipment) should be avoided. Patients who are going to be exposed to direct sunlight should be offered sunscreen creams that block ultraviolet light.

Operating machinery—see ‘Driving’, p.48.

Contraindications

Contraindications to the use of antipsychotic drugs include:

central nervous system depression.

comatose states.

phaeochromocytoma.

pregnancy—unless absolutely necessary.

Withdrawal of antipsychotic drugs

Following long-term antipsychotic drug pharmacotherapy, withdrawal of the drug should take place gradually and under close medical supervision. It is particularly important to look out for evidence of withdrawal syndromes or relapse of the psychiatric illness (for up to 2 years following antipsychotic withdrawal).

Extrapyramidal symptoms

These are particularly likely to occur with the first-generation antipsychotic drugs haloperidol, benperidol, fluphenazine, perphenazine, trifluoperazine, prochlorperazine and first-generation antipsychotic depot medication. The most important extrapyramidal symptoms are:

acute dystonic reactions

akathisia

parkinsonism

tardive dyskinesia.

In addition, perioral tremor may rarely occur.

Acute dystonic reactions

These can involve abnormal contractions of muscles controlling movements of the tongue, face, mouth, neck and back and of muscles involved in respiratory movements. Clinical manifestations include:

grimacing

oculogyric crisis

opisthotonos

torticollis

dystonia of laryngeal and pharyngeal muscles (which may cause death).

In children and adolescents, dyskinesias are commoner than dystonias. Both dystonias and dyskinesias tend to occur acutely, usually after just the initial few doses, within 1-5 days of starting antipsychotic drug pharmacotherapy. They usually respond well to antimuscarinic (anticholinergic or antiparkinsonian) medication, usually parenterally (see Chapter 12).

Acute dystonic reactions may be misdiagnosed as epileptic seizures or even hysteria. The positive response to antimuscarinic medication of acute dystonic reactions may be considered diagnostic.

Akathisia

This is a subjective feeling of motor restlessness, in which the patient experiences a strong urge to move soon after adopting a position associated with being relatively still (such as sitting down, lying down, or adopting a standing position). It tends to occur following large initial antipsychotic drug doses, usually between 5-60 days after starting the treatment. Pharmacological management includes either reducing the antipsychotic dosage or changing antipsychotic drug. Occasionally a beta-blocker or benzodiazepine may need to be used. Note that akathisia is not solely associated with the older typical antipsychotic drugs; atypicals that can cause akathisia include clozapine, risperidone and olanzapine.

Important differential diagnoses are anxiety disorders and agitation. In the case of agitation, it may be appropriate to increase the antipsychotic dose, whereas the dose should be decreased for akathisia.

Parkinsonism

Parkinsonian symptoms may gradually manifest, with the maximum risk being between 5 days and 2 months of starting an antipsychotic drug. They are believed to be caused by antagonism at dopaminergic receptors, particularly in the basal ganglia, and may include:

bradykinesia

mask-like facies

rigidity

shuffling gait

tremor

unsteadiness.

Pharmacological management includes antipsychotic drug dose reduction or withdrawal and antimuscarinic medication (see Chapter 12).

Tardive dyskinesia

In tardive dyskinesia, involuntary abnormal waking (daytime) oro-facio-lingual movements which tend to be stereotyped, rhythmic, choreiform, and painless occur, and there may also be more widespread choreoathetoid movements or sustained dystonias. The dyskinesias are usually not present during sleep. Tardive dyskinesia usually occurs after long-term treatment or the use of high doses of antipsychotic drugs, but there have been cases following short-term treatment with low doses of these drugs. The cause is not known, and there is no effective management at present; antipsychotic drug withdrawal may not be effective. The British National Formulary makes the following important points:

‘… some manufacturers suggest that drug withdrawal at the earliest signs of tardive dyskinesia (fine vermicular movements of the tongue) may halt its full development. Tardive dyskinesia occurs fairly frequently, especially in the elderly, and [antipsychotic drug] treatment must be carefully and regularly reviewed.’

Perioral tremor

Perioral tremor, or rabbit syndrome, is an antipsychotic-induced rhythmic motion of the perioral region (mouth and lips) which is said to resemble the chewing movements of a rabbit. It is relatively rare (occurring in about 2-4% of patients treated with typical antipsychotic drugs) and tends to manifest after months or years of treatment. Its cause is not known. Pharmacological management includes a reduction in antipsychotic drug dosage (as much as is clinically prudent) and, if this is not effective (or not clinically feasible), antimuscarinic medication.

Neuroleptic malignant syndrome

This is a medical emergency that is life-threatening and requires immediate treatment.

Clinical features

The clinical features of neuroleptic malignant syndrome include:

autonomic dysfunction:

hyperthermia

labile blood pressure

pallor

sweating

tachycardia

fluctuating level of consciousness (stupor)

muscular rigidity

urinary incontinence.

It may last for up to a week after cessation of the offending antipsychotic drug; in the case of depot antipsychotic medication the neuroleptic malignant syndrome may last longer than a week.

Investigations

Blood tests may show:

raised serum creatine kinase

leucocytosis.

Management

This is a clinical emergency. The causative antipsychotic drug should be immediately stopped. The patient should be admitted as an inpatient to a medical ward where maximal supportive care should be instituted. Sometimes dantrolene or bromocriptine (a dopamine agonist) may be required.

Prognosis

There may be complications such as renal failure or respiratory failure. The overall mortality is greater than 10%.

Effects of antipsychotic drugs on brain structure

David Lewis’ group have found that chronic exposure (over 17-27 months) of macaque monkeys to the orally administered antipsychotic drugs haloperidol or olanzapine, with plasma antipsychotic levels comparable to those achieved in human patients treated with these drugs for schizophrenia, is associated with reduced brain volume (Dorph-Petersen et al., 2005), compared with a third group which received sham treatment. This group also reported a statistically significant 21% lower astrocyte number and a non-significant 13% lower oligodendrocyte number in the grey matter in the antipsychotic-exposed monkeys (the haloperidol and olanzapine groups were similar) (Konopaske et al., 2008). It is noteworthy that these findings are consistent with reports from some post-mortem studies in schizophrenia (Puri, 2011).

From the large cohort of schizophrenia patients who have undergone longitudinal MRI examinations in the Iowa Longitudinal Study, significant progressive brain changes, associated with antipsychotic use, were found in most brain regions (Ho et al., 2011). These have been summarized by Puri (2011):

‘[These changes included] reductions in volume in: total cerebral tissue; total cerebral grey matter; frontal grey matter; temporal grey matter; parietal grey matter; caudate; putamen; and thalamus. Significant increases in volume were found in: parietal white matter; lateral ventricles; and sulcal cerebrospinal fluid (CSF). After adjusting for the potential confounding effects of the other three predictor variables [follow-up duration, illness severity and alcohol or illicit drug misuse], antipsychotic treatment was found to have significant main effects on total cerebral and lobar grey matter and putamen volumes; higher antipsychotic medication dose was associated with smaller total cerebral, frontal, temporal, and parietal grey matter volumes (all independent of follow-up duration), and with a larger putamen volume. Significant treatment × time interaction effects were found for total cerebral tissue volumes, total cerebral and lobar white matter, lateral ventricular, sulcal CSF, caudate, putamen, and cerebellar volumes. Greater antipsychotic dose was associated with greater reduction in white matter, caudate, and cerebellar volumes over time, and with greater CSF volume and putamen enlargement. There were no significant main effects of the severity of alcohol or illicit substance misuse on brain volume changes apart from the lateral ventricles (increased in size) and the cerebellar volumes (decreased).’

The group also examined the issue of whether any particular type of antipsychotic drug was particularly associated with changes in brain structure (or, indeed, a lack of such an association). They split the antipsychotic drugs into the following three groups: first-generation antipsychotics, clozapine, and non-clozapine second-generation antipsychotics (Ho et al. 2011). These results have been summarized by Puri (2011):

‘All three classes of drug were found to be associated with significant changes in brain volumes. Higher typical antipsychotic doses were

associated with smaller total cerebral grey matter and frontal grey matter volumes and with higher putamen volumes; higher doses of non-clozapine atypical antipsychotics were associated with lower frontal and parietal grey matter volumes and with higher parietal white matter, caudate, and putamen volumes; higher clozapine doses were associated with smaller total cerebral and lobar grey matter volumes and with larger sulcal CSF volumes and smaller caudate, putamen, and thalamic volumes.’

associated with smaller total cerebral grey matter and frontal grey matter volumes and with higher putamen volumes; higher doses of non-clozapine atypical antipsychotics were associated with lower frontal and parietal grey matter volumes and with higher parietal white matter, caudate, and putamen volumes; higher clozapine doses were associated with smaller total cerebral and lobar grey matter volumes and with larger sulcal CSF volumes and smaller caudate, putamen, and thalamic volumes.’

Elderly patients

The British National Formulary points out that antipsychotics are associated, in elderly patients with dementia, with ‘a small increased risk of mortality and an increased risk of stroke or transient ischaemic attack.’ It also points out that elderly patients have a particular susceptibility to:

postural hypotension

hyperthermia

hypothermia.

The British National Formulary recommends the following in respect of antipsychotic medication in elderly patients.

Such medication should not be used to treat mild to moderate psychotic symptomatology.

Initial doses should be reduced (≤ half the adult dose) and factor in body mass, comorbidity, and any other medication being taken.

It should be regularly reviewed.

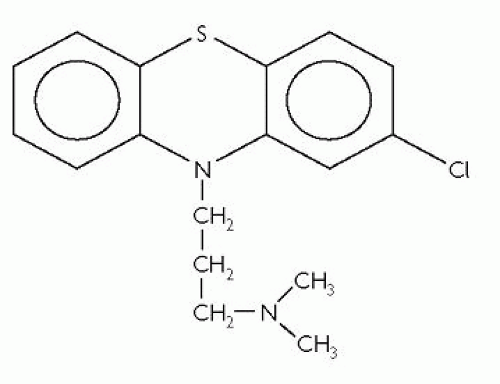

Chlorpromazine

Chlorpromazine is the archetypal typical antipsychotic. It is a phenothiazine with an aliphatic side-chain attached to the nitrogen-bridge. Its molecular structure is shown in Fig. 3.3.

The adult oral antipsychotic dose is usually between 75-300mg daily. Up to 1000mg (1g) may be required daily in extreme cases. The doses used in the elderly are a third to a half of these doses.

For children aged between 1-6 years, the recommended British National Formulary dose is 500 micrograms per kilogram body mass every 4-6 hours, up to a maximum of 40mg daily. For children aged between 6-12 years, the maximum dose recommended is 75mg daily.

The antipsychotic dose by deep intramuscular injection for adults is 25-50mg every 6-8 hours. For children, the recommended British National Formulary dose is 500 micrograms per kilogram body mass every 6-8 hours, up to a maximum of 40mg daily for those aged between 1-6 years, and up to a maximum of 75mg daily for those aged between 6-12 years.

For rectal administration, 100mg chlorpromazine base in the form of a rectal suppository should be taken to be the equivalent of 20-25mg chlorpromazine hydrochloride by intramuscular injection, and the equivalent of 40-50mg chlorpromazine base or chlorpromazine hydrochloride orally.

Chlorpromazine has a wide range of side-effects, many of which are thought to relate to antagonist activity to neurotransmission by:

dopamine

acetylcholine—muscarinic receptors

adrenaline/noradrenaline

histamine.

Antidopaminergic action on the tuberoinfundibular pathway (see Chapter 2) can lead to hyperprolactinaemia owing to the prolactin-inhibitory factor action of dopamine. In turn, hyperprolactinaemia can lead to:

galactorrhoea

gynaecomastia

menstrual disturbances

reduced sperm count

reduced libido.

Antidopaminergic action on the nigrostriatal pathway (see Chapter 2), which has important functions relating to sensorimotor coordination, can cause extrapyramidal symptoms. These have been described earlier.

Central antimuscarinic (anticholinergic) actions may give rise to:

convulsions

pyrexia.

Peripheral antimuscarinic (anticholinergic) actions may cause:

blurred vision

dry mouth

constipation

nasal congestion

urinary retention.

Antiadrenergic actions can lead to:

ejaculatory failure

postural hypotension.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree