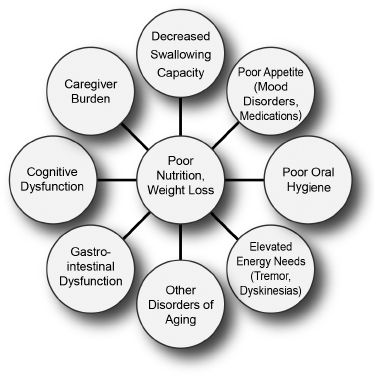

19 NUTRITIONAL CONSIDERATIONS Good nutrition is essential to maintain the well-being of individuals with neurological disease. There are several reasons why nutrition is important in movement disorders: Patients will often discuss nutrition with their primary neurologist or primary care physician. All of the reasons listed above suggest that physicians caring for individuals with movement disorders should be familiar with appropriate nutritional strategies for these patients. This chapter is structured to discuss the malnourished patient and nutritional issues with respect to the various movement disorders (ie, PD and other parkinsonian disorders, Huntington’s disease [HD] and other choreiform disorders, dystonia, and ataxia). These sections are followed by a discussion of nutritional supplements. Unintended weight loss is simply defined as a decrease in body weight that is not voluntary. Weight loss can occur with decreased food intake, increased metabolism, or both. Individuals with movement disorders should be weighed periodically as part of a routine neurological evaluation. Significant weight loss (<10% of body weight) that is unintended should prompt a discussion of potential causes. Various parkinsonian disorders, choreiform disorders, essential tremor, and ataxic disorders can all be similarly associated with weight loss. Weight loss in movement disorders may be due not only to decreased intake but also to changes in energy demands (in some cases, individuals with severe tremor, dyskinesia, or chorea may have associated weight loss).1,2 Unintentional weight loss can have similar causes across movement disorders (Figure 19.1). Figure 19.1 Nutritional assessment and intervention are important components of overall care in individuals with movement disorders. The purpose of this chapter is to discuss factors that may result in poor nutrition in the various movement disorders and strategies for their evaluation and management. Helping patients become aware of their dietary habits and energy needs, and educating them about the elements of a balanced diet as well as techniques for altering poor eating habits, can be an important part of the management of nutrition in PD. Patients should eat a balanced diet with sufficient fiber and fluid to prevent constipation. Individuals with PD may have many of the barriers to nutrition identified in Figure 19.1. Management strategies tailored to each assessed need should be formulated. Increased oral transit time is a common finding in PD. As discussed in Chapter 18, all phases of swallowing can be involved. The early phases (oral and pharyngeal) of swallowing are most affected. Modified barium swallow examination or videofluoroscopic assessment may be needed. There is no universal approach to the management of dysphagia in PD. Management can be challenging because dysphagia in PD invariably does not respond well to pharmacologic treatment for the motor symptoms of PD. Current management includes the following: Individuals with weight loss should specifically be asked about appetite. Dopaminergic therapy can change appetite. Levodopa, for example, commonly decreases appetite and may cause nausea. Dopamine agonists, on the other hand, may increase appetite. A mood disorder, such as depression or anxiety, may also impact appetite. Management may include the following: Treatment should be tailored to the patient. Autonomic dysfunction is a common complication of PD. Although overshadowed by motor dysfunction in many patients, a large number of patients with PD experience significant effects of autonomic dysfunction, including constipation, urinary problems, impotence, orthostasis, impaired thermoregulation, and sensory disturbances. Gastrointestinal manifestations may in particular impact nutrition. Caregivers of individuals with PD, especially spouses, face an increasing burden with time, particularly in the later stages of disease, when the rate of depression for caregivers is higher.14 Caregivers may themselves be ill or older. Increasing problems with activities of daily living may result in decreased overall hygiene, including decreased oral hygiene, which may affect the patient’s capacity to eat. Evidence of malnutrition in a patient with PD should prompt a full psychosocial evaluation, including the following: Medical management in PD has significant nutritional ramifications. Dopaminergic medications may cause nausea and vomiting in some patients. Medications may also cause other side effects that impact nutrition. Conversely, protein intake may interfere with medication absorption. The effects of medical therapy on overall nutritional status should be attended to. Specific issues include the following:

Nutrition may impact mobility, cognition, and swallowing function. Movement disorders, by definition, result in changes in mobility and may lead to a decreased capacity to perform activities of daily living, such as cooking and shopping.

Nutrition may impact mobility, cognition, and swallowing function. Movement disorders, by definition, result in changes in mobility and may lead to a decreased capacity to perform activities of daily living, such as cooking and shopping.

Cognitive dysfunction may impact the capacity to plan healthy meals.

Cognitive dysfunction may impact the capacity to plan healthy meals.

Parkinson’s disease (PD), other parkinsonian disorders, and many causes of chorea and ataxia can be associated with dysphagia.

Parkinson’s disease (PD), other parkinsonian disorders, and many causes of chorea and ataxia can be associated with dysphagia.

Poor nutrition in movement disorders may contribute to weight loss. Conversely, decreased levels of activity may lead to a sedentary lifestyle and obesity, exacerbating the underlying neurological disability.

Poor nutrition in movement disorders may contribute to weight loss. Conversely, decreased levels of activity may lead to a sedentary lifestyle and obesity, exacerbating the underlying neurological disability.

Finally, individuals with movement disorders often actively pursue both traditional and nontraditional treatment alternatives, vitamin therapies, and herbal remedies, which are frequently proposed for the management of many symptoms.

Finally, individuals with movement disorders often actively pursue both traditional and nontraditional treatment alternatives, vitamin therapies, and herbal remedies, which are frequently proposed for the management of many symptoms.

THE MALNOURISHED PATIENT: UNINTENDED WEIGHT LOSS IN MOVEMENT DISORDERS

Decreased ability to swallow. Patients who have trouble swallowing eat more slowly, are satiated (satisfied) more easily, and eat less.

Decreased ability to swallow. Patients who have trouble swallowing eat more slowly, are satiated (satisfied) more easily, and eat less.

Factors leading to poor nutrition in patients with movement disorders.

Poor oral hygiene. Motor deficits associated with difficulties in performing activities of daily living, such as attending to hygiene needs, may contribute to poor dentition and impact nutrition.

Poor oral hygiene. Motor deficits associated with difficulties in performing activities of daily living, such as attending to hygiene needs, may contribute to poor dentition and impact nutrition.

Elevated energy needs. Patients who have frequent episodes of moderate to marked tremors, dyskinesia, or rigidity may burn calories faster.

Elevated energy needs. Patients who have frequent episodes of moderate to marked tremors, dyskinesia, or rigidity may burn calories faster.

Psychosocial factors. Individuals with advancing disease may progressively burden caregivers, sometimes overwhelming their capacity to provide adequate care.

Psychosocial factors. Individuals with advancing disease may progressively burden caregivers, sometimes overwhelming their capacity to provide adequate care.

Gastrointestinal dysfunction. In many disorders, such as PD and multiple system atrophy (MSA), autonomic dysfunction can affect gut function, causing reflux, constipation, and other problems.

Gastrointestinal dysfunction. In many disorders, such as PD and multiple system atrophy (MSA), autonomic dysfunction can affect gut function, causing reflux, constipation, and other problems.

Executive dysfunction. Cognitive dysfunction, particularly difficulties in planning and coordinating complex activities, can interfere with the capacity of individuals with limited support networks to plan and cook meals.

Executive dysfunction. Cognitive dysfunction, particularly difficulties in planning and coordinating complex activities, can interfere with the capacity of individuals with limited support networks to plan and cook meals.

Other disorders of aging. Although weight loss may be a unique feature of many movement disorders, unplanned weight loss may also be a sign of other medical illnesses, such as malignancy, gastrointestinal defects, chronic infections, and endocrine defects.

Other disorders of aging. Although weight loss may be a unique feature of many movement disorders, unplanned weight loss may also be a sign of other medical illnesses, such as malignancy, gastrointestinal defects, chronic infections, and endocrine defects.

NUTRITION IN PARKINSON’S DISEASE

Dysphagia

Referral for speech therapy for any patient who experiences choking or problems with swallowing. Alterations in swallowing technique may help with function.

Referral for speech therapy for any patient who experiences choking or problems with swallowing. Alterations in swallowing technique may help with function.

Changes in food consistency (soft, texture-modified diet and thickening of fluids) may be helpful for some patients.

Changes in food consistency (soft, texture-modified diet and thickening of fluids) may be helpful for some patients.

Postural adaptations and adjustments may be useful.

Postural adaptations and adjustments may be useful.

Optimizing dopaminergic medications may be helpful in some patients. Levodopa and apomorphine can improve the early phases of swallowing.

Optimizing dopaminergic medications may be helpful in some patients. Levodopa and apomorphine can improve the early phases of swallowing.

Gastrostomy feeding tube placement should be considered in patients with advanced disease.

Gastrostomy feeding tube placement should be considered in patients with advanced disease.

Botulinum toxin injection, cricopharyngeal muscle resection, and deep brain stimulation (DBS) for dysphagia in PD have been reported in a limited number of cases.

Botulinum toxin injection, cricopharyngeal muscle resection, and deep brain stimulation (DBS) for dysphagia in PD have been reported in a limited number of cases.

Currently, there is no clear evidence to recommend to the use of complementary therapies for the treatment of dysphagia in PD.

Currently, there is no clear evidence to recommend to the use of complementary therapies for the treatment of dysphagia in PD.

Limited reports on the benefits of speech therapy (eg, Lee Silverman voice therapy) suggest that it may mitigate dysphasia because it strengthens not only the speech muscles but the swallowing muscles as well.

Limited reports on the benefits of speech therapy (eg, Lee Silverman voice therapy) suggest that it may mitigate dysphasia because it strengthens not only the speech muscles but the swallowing muscles as well.

Decreased Appetite

Taking levodopa with meals. Patients who experience nausea as a side effect of levodopa may take this medication with meals. However, in the presence of wearing-off symptoms, protein competition (large amino acids in particular) can limit levodopa absorption; therefore, it may be best for the patient to take levodopa at least half an hour before meals or 2 hours after eating. The timing of levodopa dosing should be individualized.

Taking levodopa with meals. Patients who experience nausea as a side effect of levodopa may take this medication with meals. However, in the presence of wearing-off symptoms, protein competition (large amino acids in particular) can limit levodopa absorption; therefore, it may be best for the patient to take levodopa at least half an hour before meals or 2 hours after eating. The timing of levodopa dosing should be individualized.

Evaluation for and treatment of anxiety or depression. These may cause a loss of appetite or sometimes overeating.

Evaluation for and treatment of anxiety or depression. These may cause a loss of appetite or sometimes overeating.

Although some nutritional supplements, such as branched-chain amino acids, may stimulate appetite, they may induce wearing off and should be used with extra caution.3

Although some nutritional supplements, such as branched-chain amino acids, may stimulate appetite, they may induce wearing off and should be used with extra caution.3

Elevated Energy Needs

Mild dyskinesia may be a necessary compromise to maintain good motor function in levodopa-sensitive patients in the later stages of PD, and it should not automatically be a reason to alter medical therapy. A mild increase in dietary caloric intake may be an appropriate management strategy to replenish calories lost from excessive movement.

Mild dyskinesia may be a necessary compromise to maintain good motor function in levodopa-sensitive patients in the later stages of PD, and it should not automatically be a reason to alter medical therapy. A mild increase in dietary caloric intake may be an appropriate management strategy to replenish calories lost from excessive movement.

In patients with severe dyskinesia sufficient to alter energy requirements, changes in medication, including lowering the overall dose of levodopa, may help mitigate symptoms.

In patients with severe dyskinesia sufficient to alter energy requirements, changes in medication, including lowering the overall dose of levodopa, may help mitigate symptoms.

Severe tremor can increase energy requirements and can significantly interfere with quality of life. Increasing the levodopa dose or adding an agonist or anticholinergic agent may be helpful.

Severe tremor can increase energy requirements and can significantly interfere with quality of life. Increasing the levodopa dose or adding an agonist or anticholinergic agent may be helpful.

If medication alterations are not helpful for severe tremors or dyskinesia, DBS may be considered in selected patients, as discussed in Chapter 16.

If medication alterations are not helpful for severe tremors or dyskinesia, DBS may be considered in selected patients, as discussed in Chapter 16.

Autonomic Dysfunction

Gastroesophageal reflux. Poor transit through the stomach can lead to the reflux of acid into the esophagus. Gastroesophageal reflux is treatable and should not be overlooked as a cause of nausea in PD. If reflux is present, decreasing the size of meals and avoiding trigger foods like caffeine, citrus fruits, tomatoes, and alcohol should be first-line treatment. Numerous small meals and snacks that are nutrient-dense and moderate in fat and fiber may be helpful. The day’s final meal should be consumed at least 4 hours before bedtime, so that the stomach is empty before the patient lies down. Herbal remedies for dyspepsia with metallic additives should not be given because they can inhibit levodopa absorption.

Gastroesophageal reflux. Poor transit through the stomach can lead to the reflux of acid into the esophagus. Gastroesophageal reflux is treatable and should not be overlooked as a cause of nausea in PD. If reflux is present, decreasing the size of meals and avoiding trigger foods like caffeine, citrus fruits, tomatoes, and alcohol should be first-line treatment. Numerous small meals and snacks that are nutrient-dense and moderate in fat and fiber may be helpful. The day’s final meal should be consumed at least 4 hours before bedtime, so that the stomach is empty before the patient lies down. Herbal remedies for dyspepsia with metallic additives should not be given because they can inhibit levodopa absorption.

Constipation. There is evidence that the neurodegenerative process may cause constipation. Lewy body deposition has been discovered in the myenteric plexus of patients with PD.4 Slowed stool transit time may result in constipation, with changes in appetite related to a feeling of fullness and intestinal discomfort. Dietary changes form the keystone of good management for PD. The management of constipation can be conservative, pharmacologic, or both.

Constipation. There is evidence that the neurodegenerative process may cause constipation. Lewy body deposition has been discovered in the myenteric plexus of patients with PD.4 Slowed stool transit time may result in constipation, with changes in appetite related to a feeling of fullness and intestinal discomfort. Dietary changes form the keystone of good management for PD. The management of constipation can be conservative, pharmacologic, or both.

Conservative treatment includes the following recommendations:

Conservative treatment includes the following recommendations:

Drink at least eight full glasses of water each day.

Drink at least eight full glasses of water each day.

Include high-fiber raw vegetables in at least two meals per day.

Include high-fiber raw vegetables in at least two meals per day.

Oat bran and other high-fiber additives may be helpful.

Oat bran and other high-fiber additives may be helpful.

Avoid baked goods and bananas.

Avoid baked goods and bananas.

Increase physical activity; for example, walking and swimming are good.

Increase physical activity; for example, walking and swimming are good.

Discontinue medications causing constipation if possible.

Discontinue medications causing constipation if possible.

Pharmacologic treatment

Pharmacologic treatment

Consider psyllium (5.1 g twice daily) or polyethylene glycol 3350 (up to 17 mg daily) if conservative management fails.5

Consider psyllium (5.1 g twice daily) or polyethylene glycol 3350 (up to 17 mg daily) if conservative management fails.5

Avoid the chronic use of laxatives, including senna and cascara sagrada, as these are less physiologic strategies that may damage the colon with prolonged use.

Avoid the chronic use of laxatives, including senna and cascara sagrada, as these are less physiologic strategies that may damage the colon with prolonged use.

Defecatory dysfunction. Some practitioners have suggested that a paradoxical contraction of the pelvic floor musculature consistent with a pelvic floor dystonia may occur in some patients, leading to poor colonic emptying. In one study, defecatory function was improved in eight patients with PD after the administration of apomorphine.6 Botulinum toxin injections into the puborectalis muscle under ultrasonic guidance have also been reported to improve anorectal function in PD.7

Defecatory dysfunction. Some practitioners have suggested that a paradoxical contraction of the pelvic floor musculature consistent with a pelvic floor dystonia may occur in some patients, leading to poor colonic emptying. In one study, defecatory function was improved in eight patients with PD after the administration of apomorphine.6 Botulinum toxin injections into the puborectalis muscle under ultrasonic guidance have also been reported to improve anorectal function in PD.7

Sialorrhea. Sialorrhea is very common in PD, affecting more than 70% of patients. It may affect nutrition and can be embarrassing in social situations. Recent studies have shown that sialorrhea results from concomitant swallowing difficulties rather than excessive salivation.8,9 Although the use of sugar-free chewing gum or hard candy may be helpful in patients with mild symptoms, pharmacologic treatment should be considered when more aggressive interventions are warranted. Evidence-based pharmacologic treatment includes the following:

Sialorrhea. Sialorrhea is very common in PD, affecting more than 70% of patients. It may affect nutrition and can be embarrassing in social situations. Recent studies have shown that sialorrhea results from concomitant swallowing difficulties rather than excessive salivation.8,9 Although the use of sugar-free chewing gum or hard candy may be helpful in patients with mild symptoms, pharmacologic treatment should be considered when more aggressive interventions are warranted. Evidence-based pharmacologic treatment includes the following:

Glycopyrrolate (1 mg 3 times daily)10

Glycopyrrolate (1 mg 3 times daily)10

Sublingual administration of ipratropium spray and atropine ophthalmic11

Sublingual administration of ipratropium spray and atropine ophthalmic11

Botulinum toxin type A or B injections into the parotid and submandibular glands12,13

Botulinum toxin type A or B injections into the parotid and submandibular glands12,13

Xerostomia (dry mouth). Some anticholinergic medications, such as benztropine and medications used for bladder dysfunction, can cause dry mouth. The long-term effects of dry mouth include increased dental caries and gingivitis, and dry mouth can be a significant problem in individuals who already have difficulty in performing the activities of daily living, including oral hygiene. Stopping the offending medication, if possible, is usually the only effective therapy.

Xerostomia (dry mouth). Some anticholinergic medications, such as benztropine and medications used for bladder dysfunction, can cause dry mouth. The long-term effects of dry mouth include increased dental caries and gingivitis, and dry mouth can be a significant problem in individuals who already have difficulty in performing the activities of daily living, including oral hygiene. Stopping the offending medication, if possible, is usually the only effective therapy.

Cognitive and Psychosocial Factors

Home physical therapy and occupational therapy evaluation to evaluate the living situation

Home physical therapy and occupational therapy evaluation to evaluate the living situation

Social work interaction to evaluate caregiver resources

Social work interaction to evaluate caregiver resources

Dental evaluation if there is evidence of dental disease

Dental evaluation if there is evidence of dental disease

Neuropsychological evaluation to gauge the presence of significant dementia interfering with function

Neuropsychological evaluation to gauge the presence of significant dementia interfering with function

Other Disorders

Individuals with PD are subject to other disorders of aging, and abrupt changes in weight or appetite should prompt a consideration of other potential medical causes, including malignancy and endocrine abnormalities.

Individuals with PD are subject to other disorders of aging, and abrupt changes in weight or appetite should prompt a consideration of other potential medical causes, including malignancy and endocrine abnormalities.

A recent review suggested that overweight in PD seems to be associated with cardiovascular risk factors, such as hypertension, diabetes, and hypercholesterolemia.15 However, further studies are needed to put forth strong evidence of this association.

A recent review suggested that overweight in PD seems to be associated with cardiovascular risk factors, such as hypertension, diabetes, and hypercholesterolemia.15 However, further studies are needed to put forth strong evidence of this association.

Other Nutritional Considerations in Parkinson’s Disease

Levodopa-related nausea and vomiting. The initiation of levodopa may cause nausea and vomiting. Management strategies to mitigate levodopa-induced nausea include these:

Levodopa-related nausea and vomiting. The initiation of levodopa may cause nausea and vomiting. Management strategies to mitigate levodopa-induced nausea include these:

When a patient starts levodopa, an initial dose of half a tablet 3 times daily should be used to decrease the chance of nausea.

When a patient starts levodopa, an initial dose of half a tablet 3 times daily should be used to decrease the chance of nausea.

Initially, patients may need to take levodopa with food.

Initially, patients may need to take levodopa with food.

Ginger tea and crystallized ginger, which can be chewed, may help some patients.

Ginger tea and crystallized ginger, which can be chewed, may help some patients.

Extra carbidopa (25- to 50-mg dose, taken with levodopa) may help mitigate the peripheral effects of levodopa (when converted to dopamine outside the central nervous system), including nausea.

Extra carbidopa (25- to 50-mg dose, taken with levodopa) may help mitigate the peripheral effects of levodopa (when converted to dopamine outside the central nervous system), including nausea.

Domperidone, available in pharmacies outside the United States and occasionally in compound pharmacies, has proved to be effective and safe in PD and can also mitigate nausea.

Domperidone, available in pharmacies outside the United States and occasionally in compound pharmacies, has proved to be effective and safe in PD and can also mitigate nausea.

Prochlorperazine (Compazine) and metoclopramide (Reglan) are to be avoided because they block dopamine receptors and can increase parkinsonian symptoms.

Prochlorperazine (Compazine) and metoclopramide (Reglan) are to be avoided because they block dopamine receptors and can increase parkinsonian symptoms.

Levodopa–protein interaction. Large, neutral amino acids compete with levodopa for uptake, both from the gut and across the blood–brain barrier. Interactions between protein and levodopa usually become evident in patients in the later stages of PD. Management strategies include the following:

Levodopa–protein interaction. Large, neutral amino acids compete with levodopa for uptake, both from the gut and across the blood–brain barrier. Interactions between protein and levodopa usually become evident in patients in the later stages of PD. Management strategies include the following:

The immediate-release formulation of levodopa is taken 30 minutes before meals.

The immediate-release formulation of levodopa is taken 30 minutes before meals.

Protein restriction during the day has been recommended by some practitioners.16 This strategy works as a short-term solution but may not be as effective as a long-term solution.4 It is not tolerated by patients and results in a low energy intake.

Protein restriction during the day has been recommended by some practitioners.16 This strategy works as a short-term solution but may not be as effective as a long-term solution.4 It is not tolerated by patients and results in a low energy intake.

Domperidone can improve both gastric emptying and levodopa absorption. It can combat nausea and vomiting in extreme cases.

Domperidone can improve both gastric emptying and levodopa absorption. It can combat nausea and vomiting in extreme cases.

Unplanned weight gain. Unplanned weight gain can be an idiosyncratic side effect of dopamine agonists such as pramipexole (Mirapex), rotigotine (Neupro patch), and ropinirole (Requip). They may cause an increased caloric intake, or they may increase fluid retention. Compulsive eating, particularly sweets and carbohydrates, may also occur. Amantadine may also increase fluid retention. Management may include the following:

Unplanned weight gain. Unplanned weight gain can be an idiosyncratic side effect of dopamine agonists such as pramipexole (Mirapex), rotigotine (Neupro patch), and ropinirole (Requip). They may cause an increased caloric intake, or they may increase fluid retention. Compulsive eating, particularly sweets and carbohydrates, may also occur. Amantadine may also increase fluid retention. Management may include the following:

Physical activity can be increased.

Physical activity can be increased.

Decreased salt intake may help in some cases.

Decreased salt intake may help in some cases.

Discontinuation or alteration of the dose of the offending medication may be necessary.

Discontinuation or alteration of the dose of the offending medication may be necessary.

Obsessive behaviors related to dopamine agonists are idiosyncratic and do not appear to be strictly dose-related. Typically, these problems are not treatable except by stopping the offending medication. The observation of obsessive eating should prompt questions about other obsessive behaviors, such as gambling and sexual obsessions.

Obsessive behaviors related to dopamine agonists are idiosyncratic and do not appear to be strictly dose-related. Typically, these problems are not treatable except by stopping the offending medication. The observation of obsessive eating should prompt questions about other obsessive behaviors, such as gambling and sexual obsessions.

DBS, in particular DBS of the subthalamic nucleus (STN), may result in weight gain for unclear reasons.

DBS, in particular DBS of the subthalamic nucleus (STN), may result in weight gain for unclear reasons.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree