THE EFFECTIVENESS OF OBSERVATIONAL PAIN ASSESSMENT IN OLDER PERSONS WITH DEMENTIA

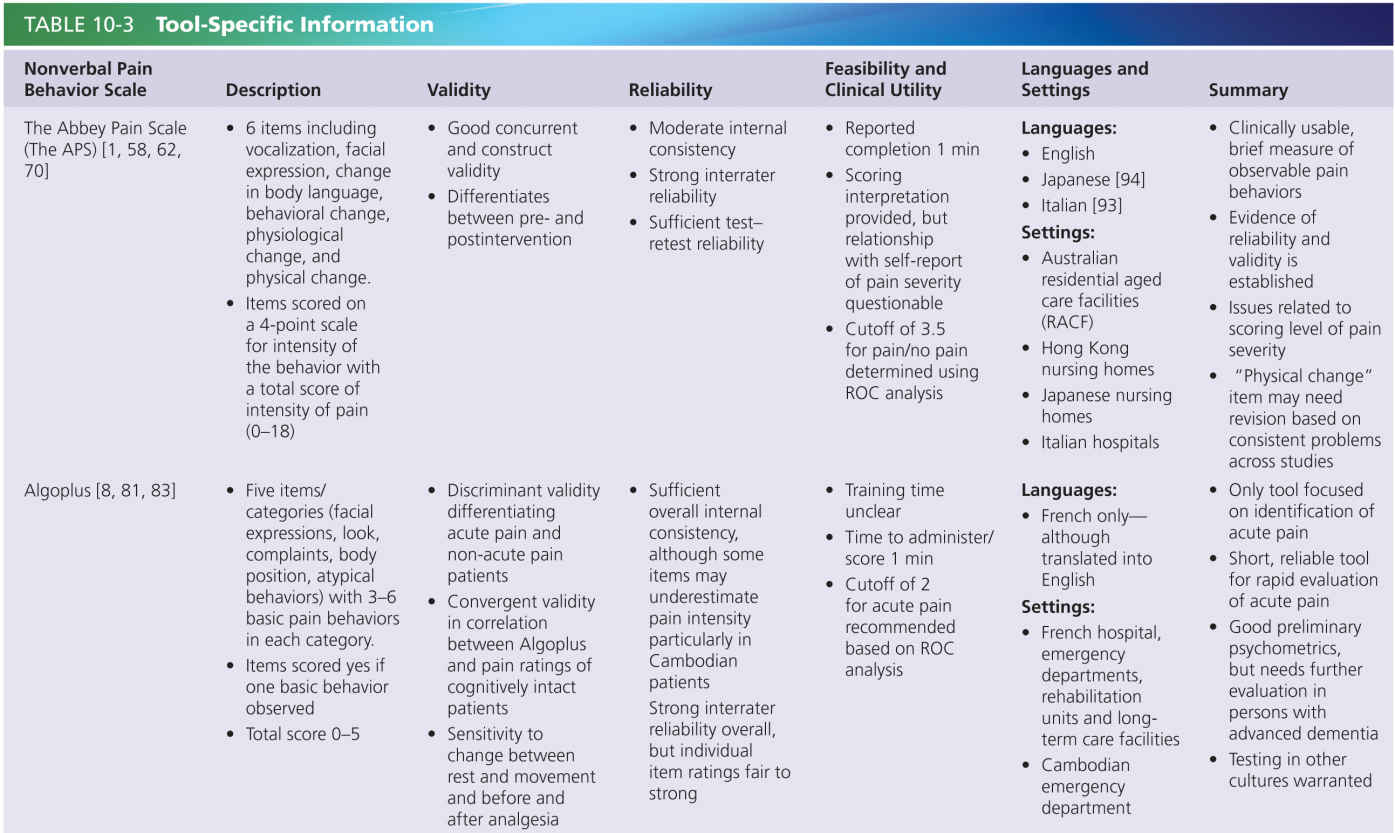

Assessing pain is challenging, especially for staff caring for older persons with dementia. A pressing question is whether improved recognition and assessment of pain in dementia actually leads to treatment and improvement in quality of life. Several studies suggest that pain assessment by using an observational tool increases awareness of pain and may facilitate an improvement in the assessment and management of pain in dementia [53, 59, 62, 64, 83, 89]. Lukas et al. [62] showed that the use of instruments such as pain tools improved recognition of the presence or absence of pain by over 25% above chance. Furthermore, it seems that tools with items capturing facial action units common in pain demonstrated higher levels of sensitivity, reliability, and validity [89].

All observational tools rely on a proxy report that is most often performed by nursing staff. The regular assessment and attention to pain shows not only positive effects on residents’ outcomes, but also improves staff outcomes such as work stress [30].

DIRECTIONS OF FUTURE DEVELOPMENTS TO IMPROVE THE RECOGNITION AND QUANTIFICATION OF PAIN IN PERSONS WITH DEMENTIA

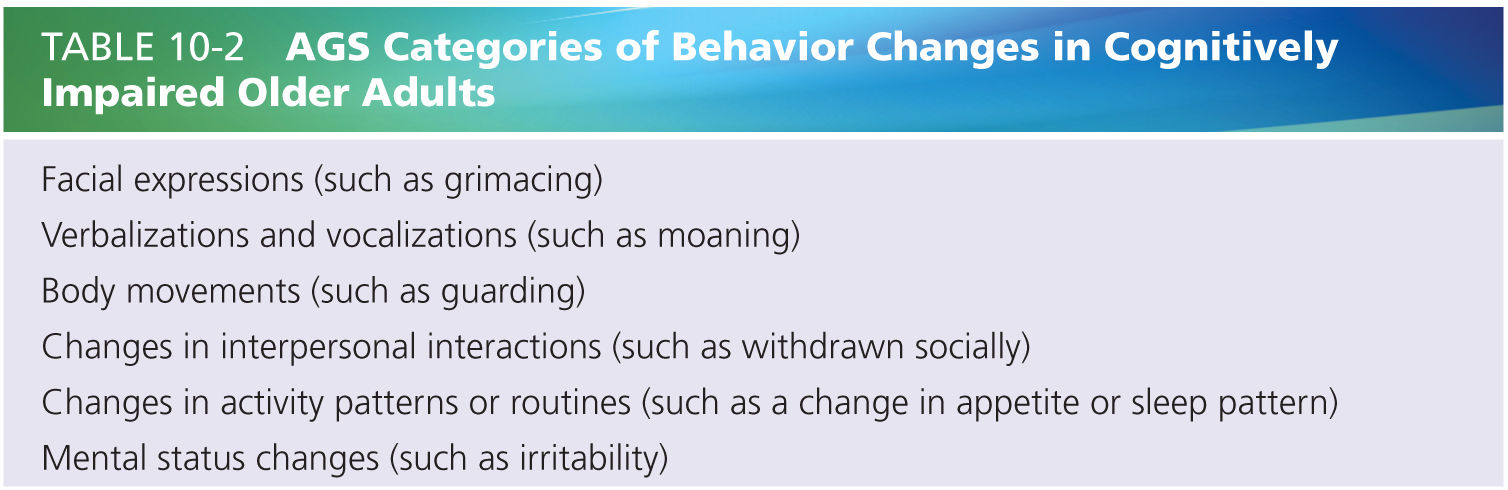

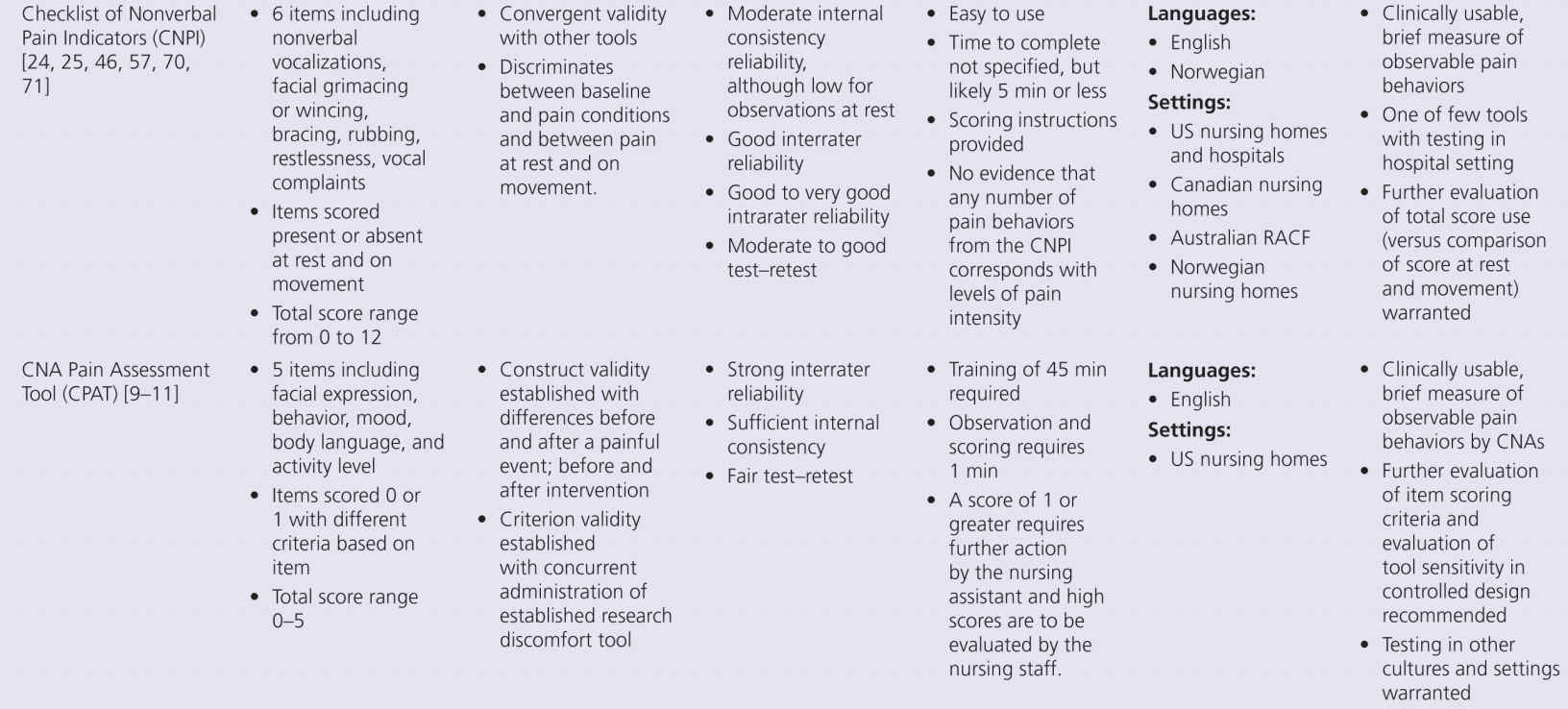

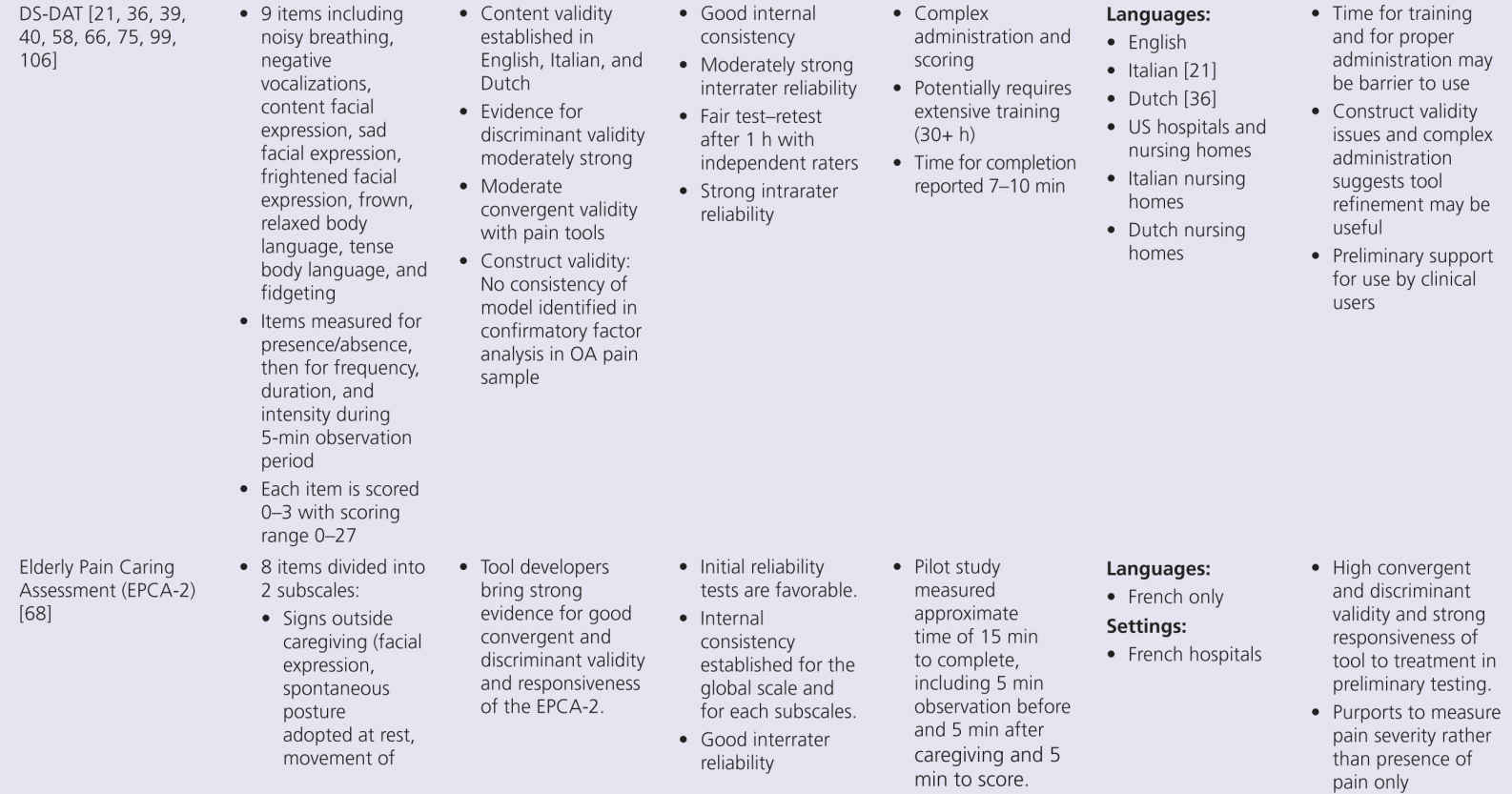

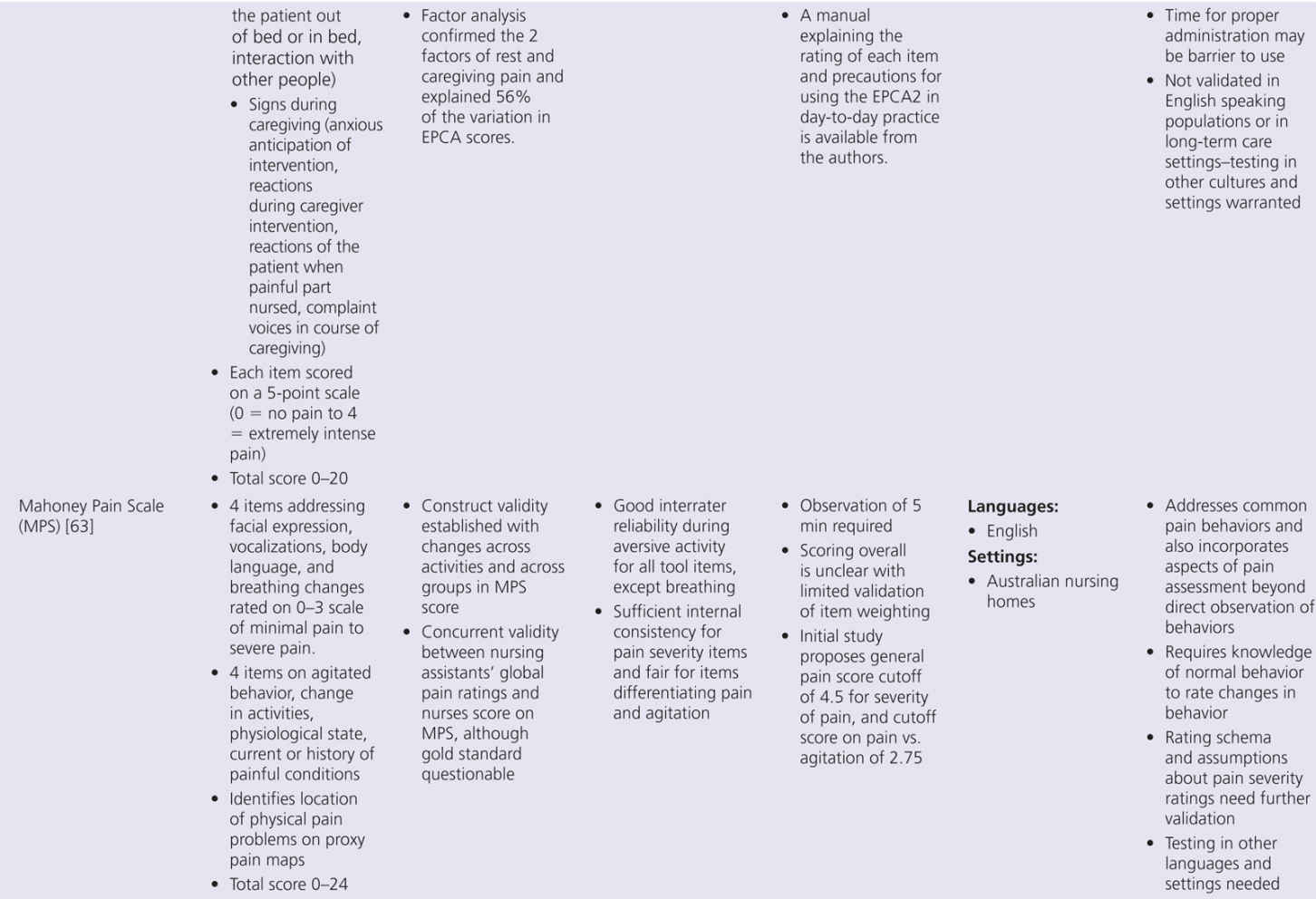

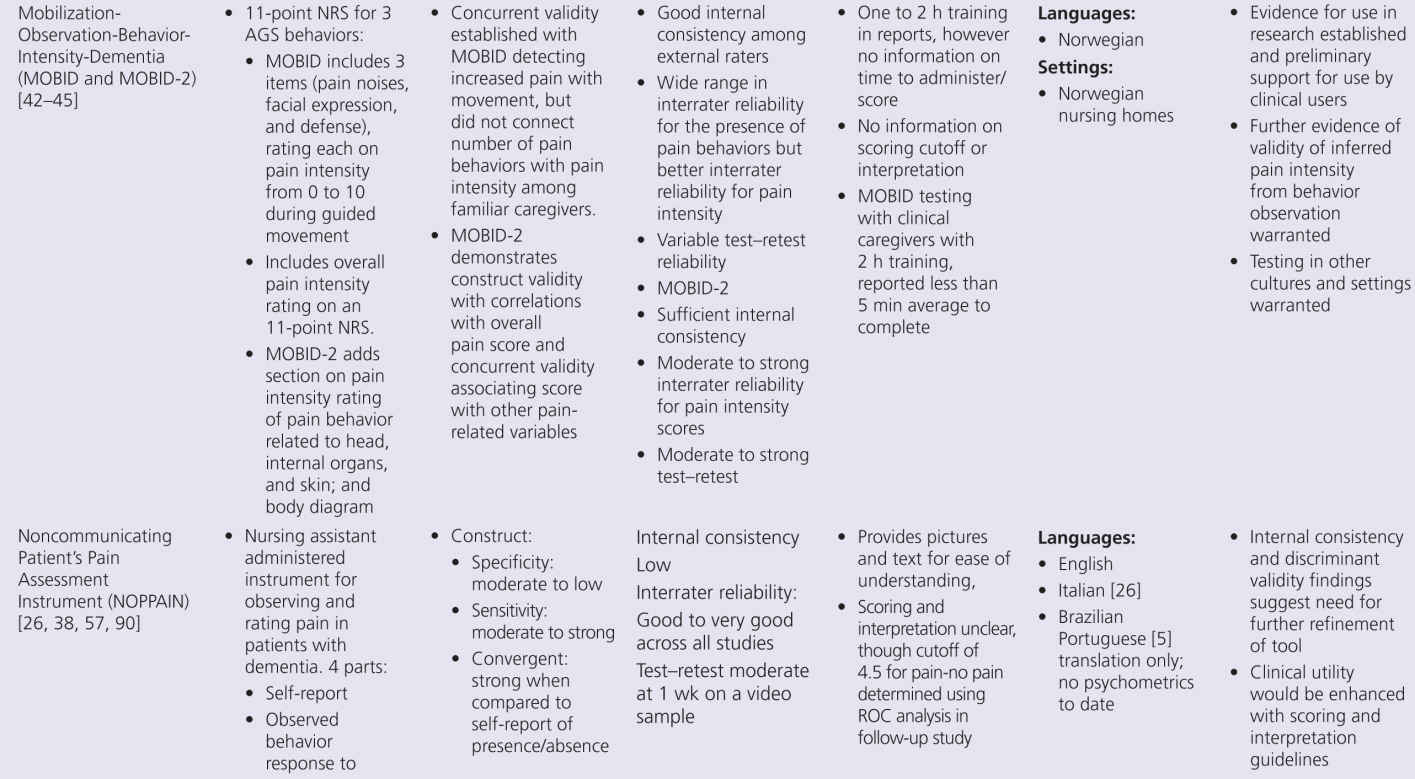

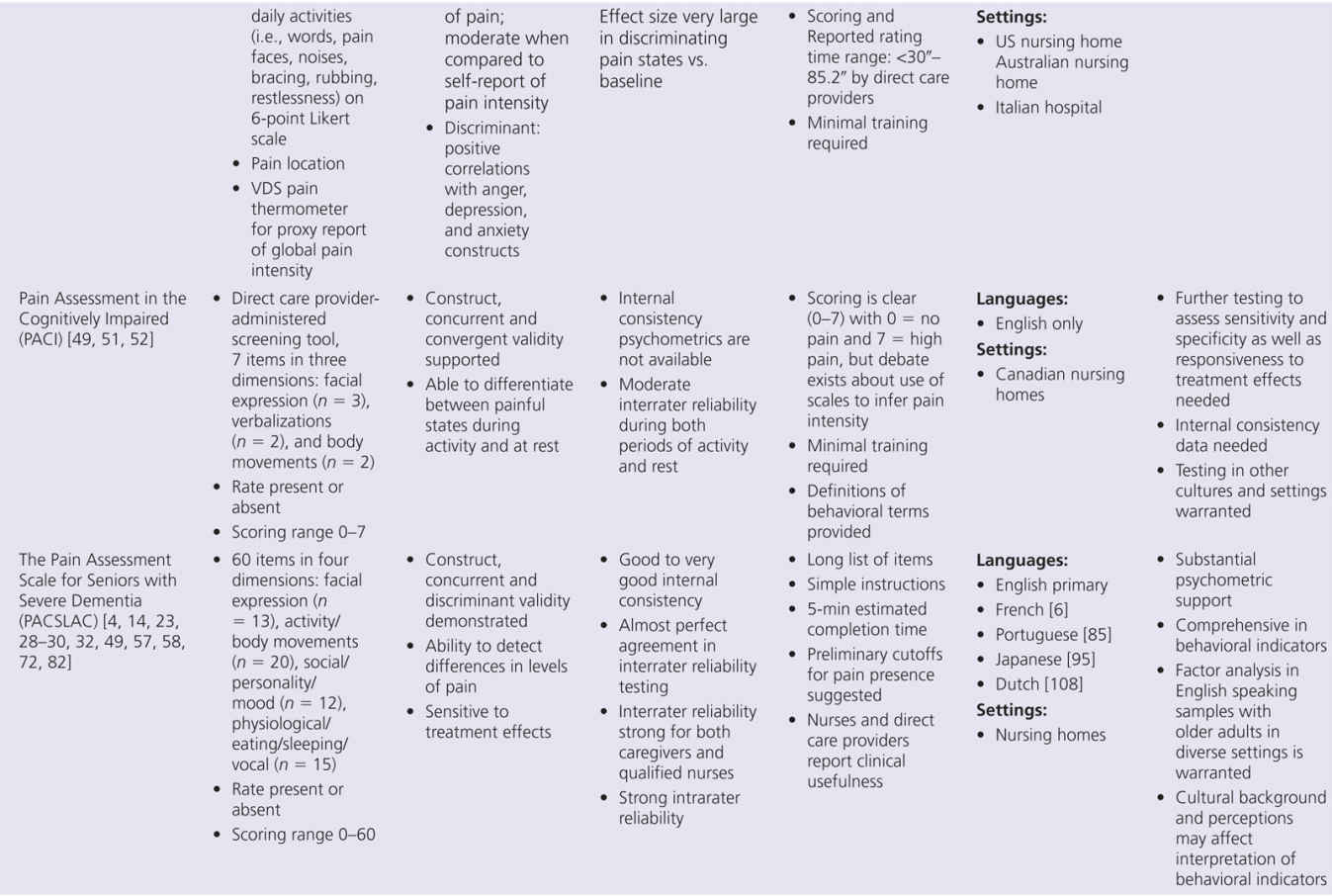

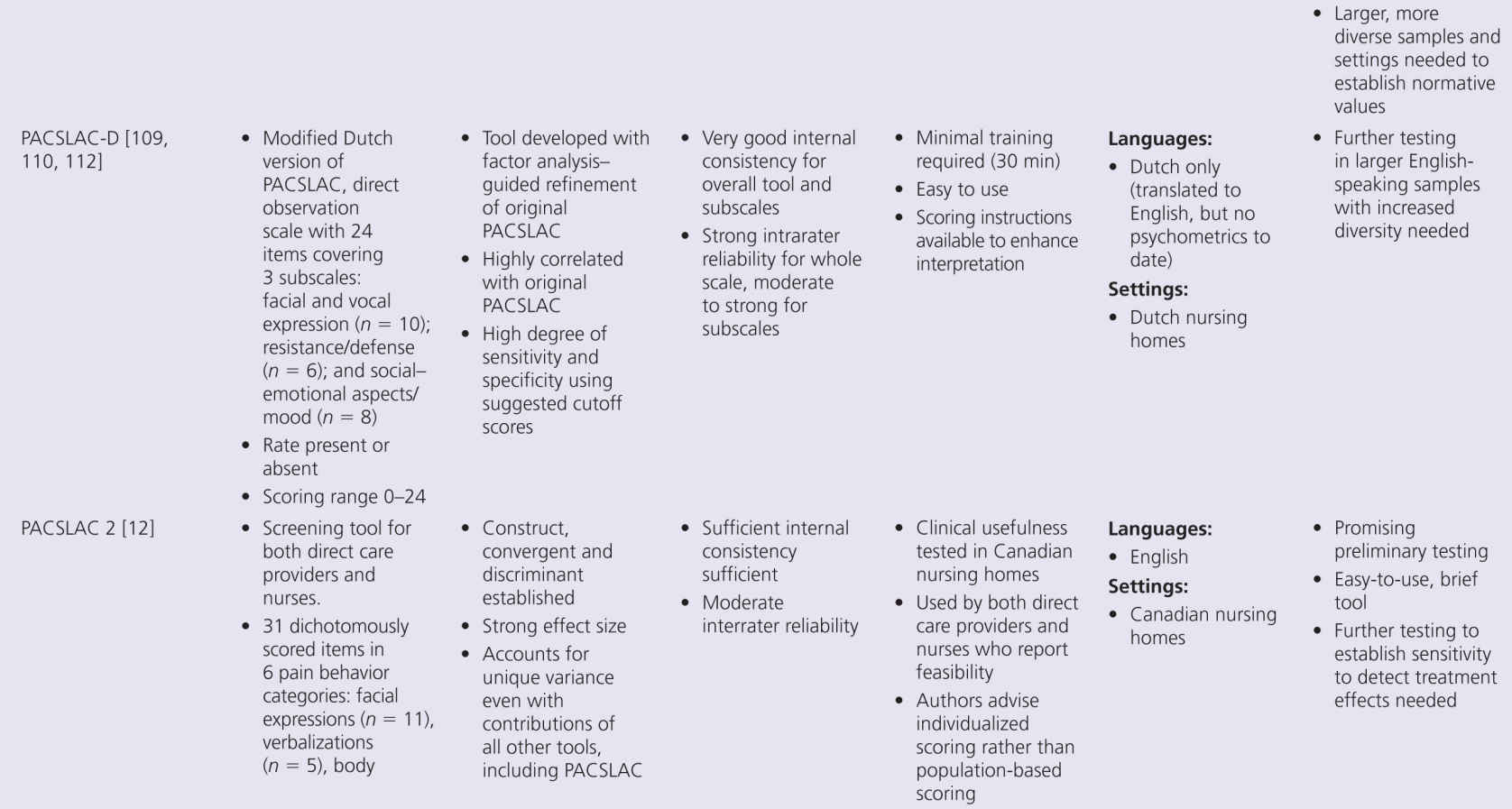

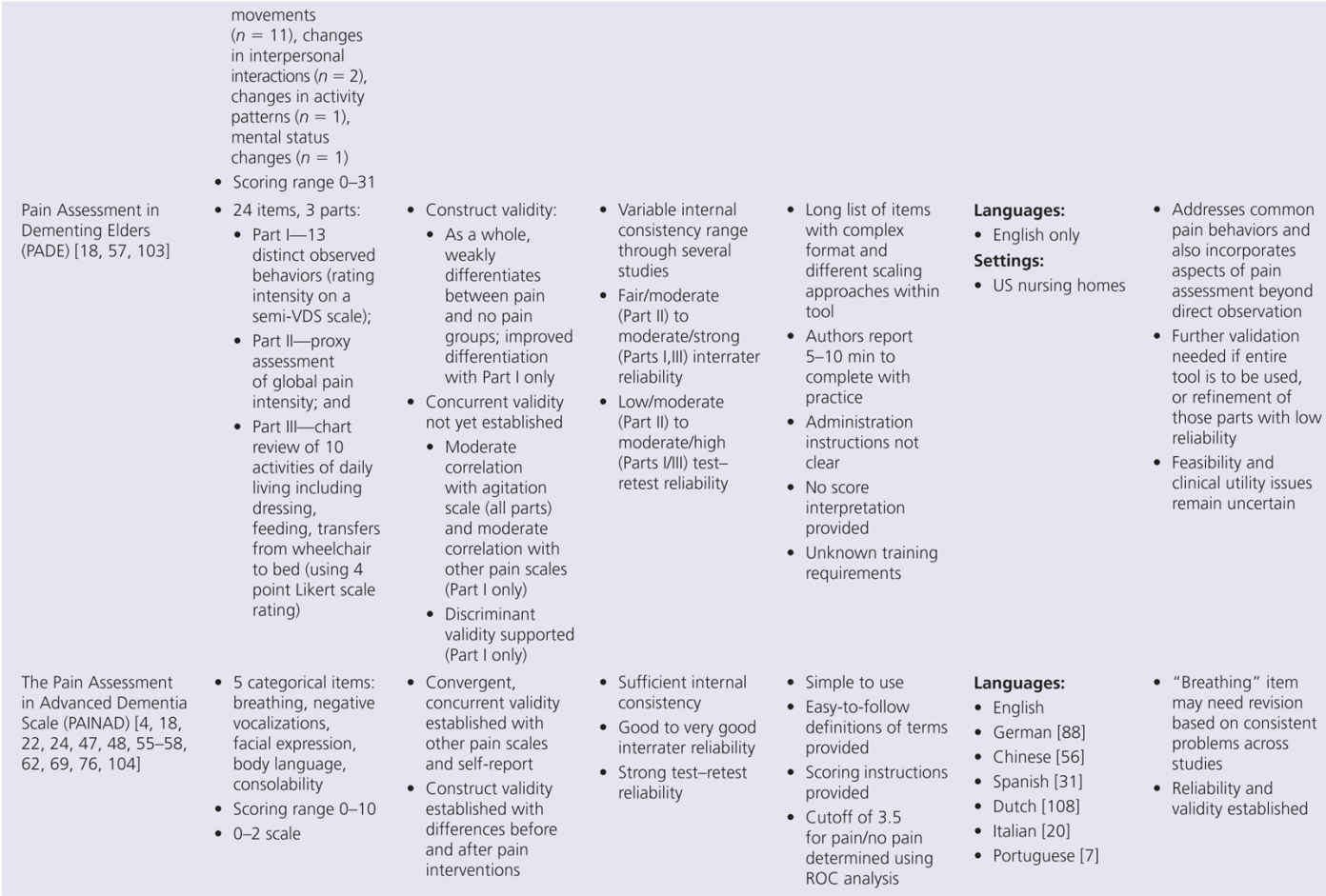

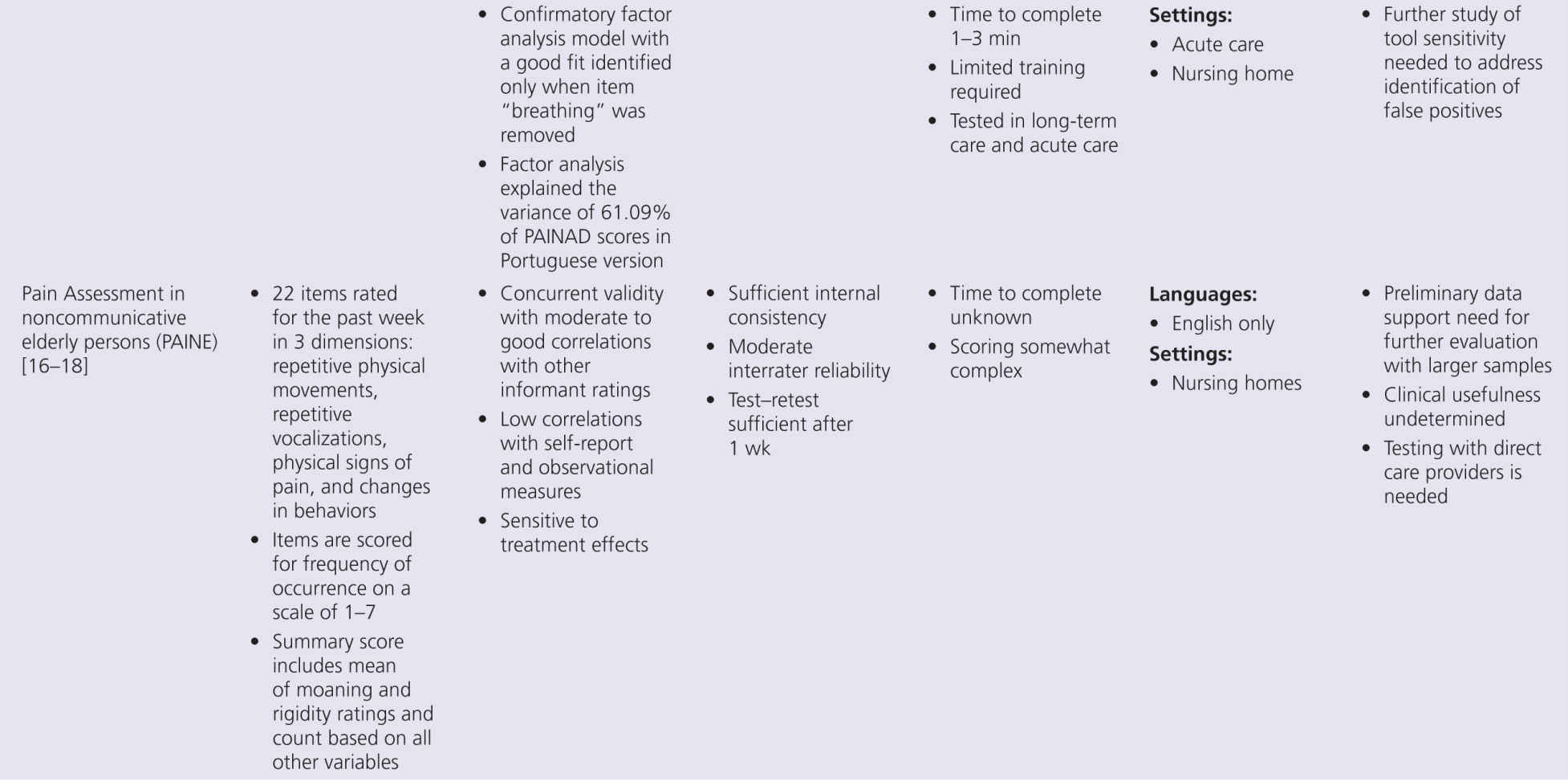

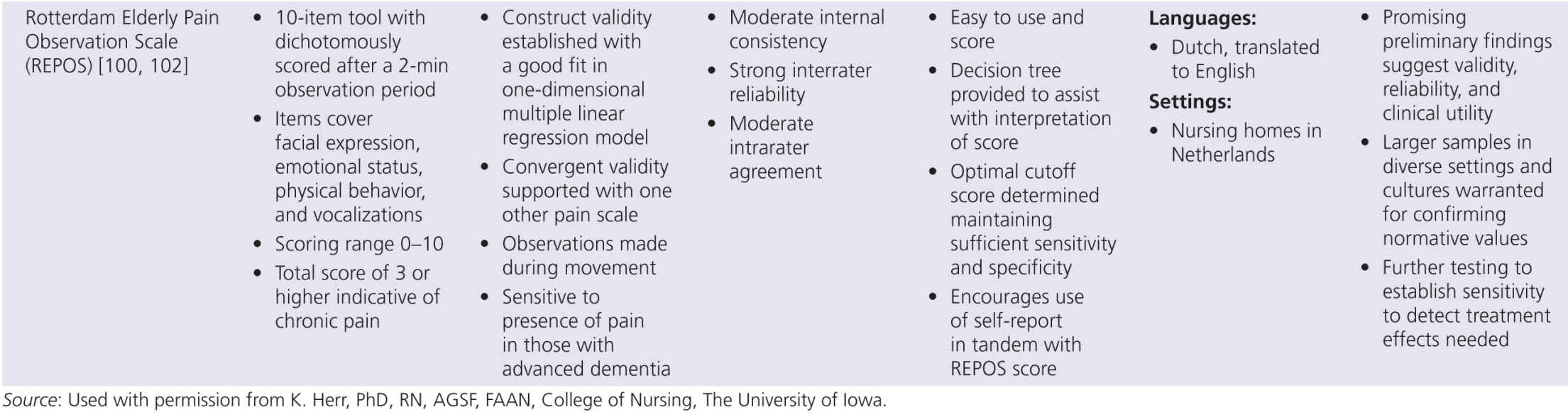

Although pain research in persons with dementia has expanded greatly in the past decade, several key aspects of pain assessment remain poorly understood. Although progress has been made, many areas require further research. However, the state of the science on available tools must consider the developmental stage of tool evolution. Clinical utility is a key factor that drives acceptability and use of these tools. Less useful scales slowly disappear while better tools remain. Yet no available tool meets all required standards of psychometric soundness and generalizability across setting/populations. The goal of a common tool used across all countries and settings is not likely to be met, although it is clear from the summary in Table 10-2 that many tools are being translated and tested in different countries. The benefit of examining differences in pain experience and response across settings and countries would be advanced with valid tool translations and psychometric testing.

The proliferation of nonverbal pain tools reinforces the lack of a single acceptable standard tool, but also suggests there may be more benefit focusing on refinement of existing tools, rather than continued development of new tools unless they really open up new possibilities. This problem can be addressed by additional refinement that focuses on usability and establishing reliability and validity across populations and by future collaboration between experts in this multidisciplinary field of science. Within Europe, there is an action entitled, “Pain assessment in patients with impaired cognition, especially dementia.” This European Cooperation in Science and Technology (COST) Action, enabled by the EU Research and Technological Development of the seventh Framework Program, brings together experts from a wide range of scientific disciplines to develop a comprehensive and internationally accepted assessment toolkit for older adults targeting various subtypes of dementia (http://www.cost-td1005.net.).

Further efforts are needed, and we will address some of the future challenges. To improve the value and clinical usefulness of behavioral tools, one of the first challenges will be to clarify what observational behavioral pain cues are most sensitive to pain for which persons. Challenging behavior displayed by persons with dementia, such as agitation, resistance, and screaming, are signals for possible existence of pain. However, these behaviors can also be caused by the dementia or by dementia-related anxiety or depression. There is an urgent need to better understand the complex relationship between pain and challenging behavior.

Currently, all tools are quite generic in terms of items used, and, in general, tools are developed to assess pain in the broad category of nonverbal older persons with dementia. However, persons with dementia are very heterogeneous in terms of neuropathology, type of dementia, cognitive and physical impairments, and severity of the dementia. At this point, though, our knowledge in differentiating pain indicators among these groups is in its infancy. Growth in this area will be crucial given findings regarding the impact of neuropathology on pain behaviors. For example, persons with Alzheimer dementia (AD) may report less pain while vascular dementia (VaD) persons may show enhanced pain responses [87]. In addition, pain behaviors may be dependent on dementia stages, as a very recent study by Kaasalainen and colleagues [50] showed that persons with intact verbal capacity displayed different behaviors compared to nonverbal dementia persons. However, the interrelatedness of neuropathology and dementia stages on pain behaviors is not fully known.

Nursing homes are the most common setting for conducting research on pain in dementia. The context always needs to be taken into consideration, but little research is available to guide assessment practices and decisions in settings other than nursing homes. There are differences between the assessment of pain in acute hospital care and in institutionalized long-term care facilities, not only in the type of pain experiences but also in terms of interpersonal professional relations between the staff and the person with dementia. In-depth knowledge of the older adult and their needs is definitely an advantage when it comes to the assessment of pain in this nonverbal population. These contextual aspects are rarely addressed.

Another key area for the near future of pain research in dementia relates to the scoring methods and cutoffs of observational pain tools available to improve the interpretation of scores and enhance their value in evaluating pain. Most of the tools use a total score by summing up the individual items. Usually there is no weighting of items, and recent evidence regarding the sensitivity of facial items suggests attention to the importance of selected indicators is needed. On the other hand, certain specific behaviors are strongly related (e.g., grimacing and frowning). Hardly any of the scales have clear proven cutoff scores, something urgently needed in daily clinical practice to guide treatment decisions. Some of the more frequently used and more mature tools do report on (preliminary) cutoffs to enhance scoring interpretation, such as the PAINAD [111]. While studies predominantly focus on the presence of pain, recent literature suggests that behavioral tools may also be used to determine pain intensity in older persons with moderate–severe cognitive impairment [62]. The study of Lukas and colleagues [62] was the first to provide support for the use of observational pain assessment tools to help identify both the presence and also the intensity of pain. While others are more hesitant to link behavioral cues to pain intensity, research by Horgas and colleagues suggested that the total number of pain behaviors was significantly related to self-reported pain intensity in cognitively intact older people [37].

However, a gap remains in determining what level or score on an observational tool represents mild, moderate, or severe pain. Although more evidence is needed to support this possible linearity, having an observational tool that would be helpful in assessing pain intensity would be a step toward usability.

The feasibility of pain assessment in nonverbal older adults with dementia may be enhanced through innovative opportunities and possibilities. Many digital applications are currently being developed to ease the scoring of tools at the bedside. An example is the Abbey scale, now available as an application for Android and IPad. More advanced innovative systems based on behavioral facial expressions to monitor pain automatically are also being developed.

Last but not least, we emphasize that proper assessment and management of pain in older people with dementia using behavioral pain cues does require staff training—not only to help the staff become acquainted with tools available but also to discuss the potential barriers and their beliefs about pain in dementia. Because universal pain-specific cues do not exist, nurses and caregivers should know the person with dementia and their relatives in order to consult all possible resources that could reveal unique and individualized pain information. An approach in which the observational pain tool is only one aspect of an overall pain assessment process is the rule in the assessment and management of pain in dementia.

SUMMARY

The aim of this chapter was to present the current state of behavioral pain tools available to assess pain in people with dementia and to discuss challenges and possible future developments. Ongoing studies and innovative developments in pain research are likely to inform the selection of observational tools available for use in the near future.

1. Abbey J, Piller N, De Bellis A, Esterman A, Parker D, Giles L, Lowcay B. The Abbey pain scale: a 1-minute numerical indicator for people with end-stage dementia. Int J Palliat Nurs 2004;10:6–13.

2. AGS Panel on Persistent Pain in Older Persons. The management of persistent pain in older persons. J Am Geriatri Soc 2002;50:S205–24.

3. Ando C, Hishinuma M. Development of the Japanese DOLOPLUS-2: a pain assessment scale for the elderly with Alzheimer’s disease. Psychogeriatrics 2010;10:131–7.

4. Apinis C, Tousignant M, Arcand M, Tousignant-Laflamme Y. Can adding a standardized observational tool to interdisciplinary evaluation enhance the detection of pain in older adults with cognitive impairments? Pain Med 2013;15:32–41.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree