13 Osteoarthritis and Inflammatory Arthritides of the Aging Spine

Because of space limitations, osteoarthritis of the aging spine will be primarily considered in this review. Certain inflammatory arthritides will be considered as a part of the differential diagnosis. Osteoarthritis is an almost ubiquitous disease and a significant source of morbidity. Although it can affect every age demographic, it has an increasing prevalence in the elderly population.1 In the elderly, osteoarthritis is a significant source of disability and has a deleterious effect on a patient’s quality of life. Although a majority of studies have examined the effect of osteoarthritis on hip, knee, and hand joints, osteoarthritis can affect any joint in the body, including those in the spine. Spinal osteoarthritis commonly manifests with back or neck pain. The degeneration caused by spinal osteoarthritis can also result in central canal or neural foraminal stenosis, or both, which may cause neurological deficit, including radiculopathy, neurogenic claudication, or myelopathy.

Clinical Case Examples

Clinical Case #1 (Degenerative Lumbar Spondylolisthesis)

Figure 13-1 presents lumbar magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of a 67-year-old woman with a 30-year history of progressive lower back pain. This pain was exacerbated by activity and relieved by rest. She reported no associated radicular symptoms. Past medical history was significant for morbid obesity, diabetes, and osteoarthritis. Physical exam did not reveal a neurological deficit. The patient had failed to improve despite intensive conservative therapy which included high dosage opiates, physiotherapy, epidural steroid injections, and facet blocks. MRI and plain radiography (see Fig. 13-4) revealed degenerative spondylolisthesis, central canal stenosis, and bilateral synovial cysts. Lateral flexion and extension films demonstrated a 10-mm anterolisthesis of L4 on L5 with 9 mm in extension and 11 mm in flexion. Due to increasing disability and lack of response to conservative measures, the patient was referred for evaluation for surgical intervention.

Clinical Case #2 (Degenerative Cervical Spondylosis)

Figure 13-2 presents axial computed tomography (CT) myelogram images of a 79-year-old woman with moderate neck pain and progressive difficulty with ambulating during the past 4 years. At presentation, the patient was wheelchair bound with limited ability to transfer. Past medical history was significant for osteoarthritis, atrial fibrillation, and multiple peripheral neuropathies. Physical examination revealed gross lower extremity hyperreflexia and weakness and was consistent with myelopathy. Her sensation was diffusely diminished in her hands and arms, but she did have normal sensation in the C4-C5 distribution. She did not have a Hoffman sign, but had extensive hand intrinsic muscle atrophy. She did have crossed adductor reflexes. She was able to flex and extend her neck to 35 degrees and laterally rotate to 40 degrees. The patient’s CT myelogram demonstrated severe spinal cord compression at the C4-C5, C5-C6, and C6-C7 levels. There was anterolisthesis and osteophytic bulging, which resulted in severe spinal canal narrowing.

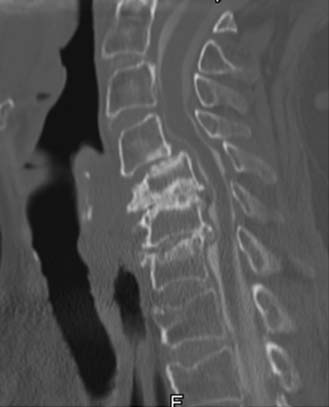

Clinical Case #3 (Atlantoaxial Instability)

Figure 13-3 presents images from a CT scan of an 85-year-old woman with severe neck pain and occipital neuralgia. The pain had been progressively worsening during the past 12-month period despite analgesia. Past medical history included hypertension, hypothyroidism, and osteoarthritis resulting in bilateral knee arthroplasties. On physical exam no weakness or evidence of myelopathy was detected. Dynamic imaging revealed a C1-C2 atlantodens interval of 4 mm in neutral, increasing to 5 mm in flexion and in extension. CT imaging (see Figure 13-3) demonstrated gross evidence of atlantoaxial instability including pannus. The patient received temporary relief with a greater occipital nerve block. Because of the overwhelming disability attributable to her neck pain and occipital neuralgia, the patient was considered for surgical intervention.

Basic Science

Osteoarthritis is a complex disease and may represent a series of diseases rather than one specific disease entity.1 The consensus definition states that osteoarthritis is a result of both mechanical and biological events that destabilize the normal coupling of degradation and synthesis of articular cartilage, extracellular matrix, and subchondral bone. When clinically evident, osteoarthritis is characterized by joint pain, tenderness, limitation of movement, crepitus, and variable degrees of inflammation without systemic effects.1 Osteoarthritis affects articular joints including the knees and hips. The zygapophyseal or facet joints are the synovial joints in the spine and therefore susceptible to osteoarthritis. Spinal osteoarthritis is therefore a disease of the facet joints due to degeneration, resulting in facet joint incompetence.

Epidemiology and Risk Factors

Spinal osteoarthritis has been demonstrated through radiographic and cadaver studies to affect every adult age group.2,3 The prevalence of clinical spinal osteoarthritis increases with age, with elderly patients having the highest radiographic and symptomatic prevalence.1,3 There is also a significant gender difference in prevalence. Females are more likely than males to suffer from osteoarthritis in general. The gender difference is exacerbated after menopause and therefore greater in the elderly.1

Other risk factors besides age and gender have been reported to be associated with the development of osteoarthritis. Obesity has a strong correlation with developing osteoarthritis. This likely represents added mechanical stress to the facet joints. Previous trauma from sports activities and occupations requiring strenuous physical labor have also been associated with the development of spinal osteoarthritis.1

Pathophysiology

Osteoarthritis is a disease of the articular cartilage and underlying subchondral bone. Although the exact etiology of osteoarthritis is not known, one theory is that cartilage matrix turnover is negatively affected by degenerative forces. This disrupts the balance between cartilage synthesis and degradation. Evidence suggests that collagenase, gelatinase, and stromelysin, which are enzymes involved in cartilage degradation, are increased in osteoarthritic joints.1 The cause for this imbalance is not clear. One proposed theory is that changes to the subchondral bone instigate changes to the cartilage matrix. Radiographic evidence of subchondral bone changes is often present in patients with osteoarthritis. It is theorized that stiffening of the subchondral bone due to microtrauma results in an abnormal environment for the overlying cartilage. This increases cartilage turnover and leads to further degradation of the joint. However, the debate as to whether subchondral bone changes are a result or cause of cartilage degeneration is not settled.1

Also unsettled is the role of the inflammatory response in the pathogenesis of osteoarthritis. Localized inflammation has been demonstrated in certain stages of osteoarthritis, including mononuclear cell infiltrate and synovial hyperplasia. The exact role of this inflammation, be it causative or reactionary, is not clear. Markers of inflammation such as C-reactive protein (CRP) may be elevated as well.1 However, in general, systemic inflammation is not characteristic of osteoarthritis. Its presence would indicate that another pathology such as rheumatoid arthritis or gout should be considered.

Degenerative Mechanics

Osteoarthritic changes at the facet joints can have a cascading effect on a patient’s overall spinal health. The facet joints function as the posterolateral articulation between vertebral segments. As such, they bear weight, restrict anterior and posterior movement of the anterior column, and restrict axial rotation. Arthritic changes in these joints can promote abnormal spine mechanics, increasing degeneration. It is commonly held that facet joint arthrosis is a sequela of disc degeneration.4 However, there is evidence to suggest that facet arthrosis is a long-standing phenomenon present before evidence of disc degeneration.2 Either way, the coupling of facet joint arthritis with disc degeneration can lead to progressive degenerative changes. In the normal spine, facet joints bear between 18% and 25% of the segmental weight load.4,5 Facet joints in degenerative spines can bear upwards of 47% or more in extension.5 This leads to progressive stress on a weakened joint. Sequelae of continued stress on the weakened facet joint include osteophytosis and synovial cyst formation. These can cause radiculopathies if affecting the lumbar or cervical foramina. Specific symptoms vary by levels, with L4-L5 being the most commonly affected.5 Large osteophytes or synovial cysts coupled with anterior osteophytic change can lead to central canal stenosis. This stenosis can result in symptoms of neurogenic claudication when located in the lumbar spine, or symptoms of myelopathy when located in the cervical spine.

The atlantoaxial junction is a common site for arthritic changes, most commonly seen in rheumatoid arthritis. Although classically not associated with osteoarthritis, atlantoaxial osteoarthritis has been reported to have a prevalence ranging between 5% and 18% of patients with spinal osteoarthritis.6 True symptomatic prevalence is probably much smaller. Arthritic changes can affect the lateral mass articulations and the atlantodens articulation. Degeneration at the atlantodens articulation can produce a pannus, similar to that seen in rheumatoid arthritis, causing myelopathic symptoms due to cord compression. More commonly, osteoarthritis at the atlantoaxial junction results in neck pain. This pain generally originates in the suboccipital region. It can radiate both cranially and caudally and can present with severe occipital pain. In general, occipital pain or subaxial neck pain without a suboccipital component most likely does not represent pain from atlantoaxial osteoarthritis, and other sources of pain should be excluded. In cases where the pain generator is difficult to locate based upon symptomatology, C1-C2 facet blocks can be a diagnostic aid if they relieve the neck pain.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree