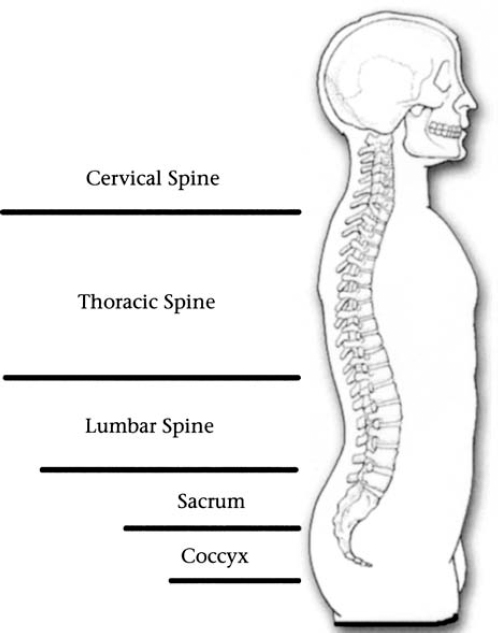

9 In addition to the common manifestations of neurofibromatosis 1 (NF1), a variety of seemingly unrelated manifestations are associated with the disorder. These less common but hardly rare manifestations of NF1 may pose significant medical challenges or cause personal discomfort unless diagnosed and managed properly. The body’s cardiovascular system consists of the heart and myriad blood vessels that supply nutrients and oxygen to every tissue. NF1 increases the risk of several cardiovascular complications, but it remains unclear why these conditions develop and how they progress naturally over the course of a person’s lifetime. Complicating the situation further, it is sometimes difficult to determine which cases of cardiovascular disease arise because of NF1 and which occur coincidentally with the disorder. What is clear is that people with NF bear disproportionately certain types of cardiovascular disease that may contribute to premature mortality in some individuals. The NF1 Cardiovascular Task Force, an expert panel convened by the National Neurofibromatosis Foundation, sifted through current evidence and concluded that the three most common cardiovascular complications of NF1 are high blood pressure (hypertension), congenital heart disease, and vasculopathy.1 A brief description of each of these conditions and the panel’s recommendation on care is provided below. Blood pressure is the force of blood as it flows from the heart to the blood vessels, and it is measured in millimeters of mercury (mm Hg). Federal guidelines define normal blood pressure2 as less than 120/80 mm Hg. The first number is a measure of systolic pressure, when the heart beats, and the second is a measure of diastolic pressure, when the heart relaxes between beats. High blood pressure is defined as 140/90 mm Hg or higher, whereas prehypertension2 is defined as 120/80 to 139/89 mm Hg. People with higher than normal blood pressure may not be aware of it until it is checked, because often no other symptoms are present. Untreated, however, high blood pressure can cause heart attack, stroke, kidney failure, and other medical problems. In fact, risk of cardiovascular disease doubles with each 20/10 mm Hg increase in blood pressure,2 starting at 115/75 mm Hg. Many people with NF1 already have hypertension or are prehypertensive and are at risk of developing high blood pressure as they grow older. High blood pressure can develop in people with NF1 for several reasons. In adults with NF1, the most common type is essential hypertension that develops for no apparent reason and is indistinguishable from that seen in the general population. Several types of secondary hypertension, which arise as a result of another condition or disease, may also occur in people with NF1. When hypertension develops in children and young adults with NF1, particularly in pregnant women, renovascular abnormalities are usually the cause. These abnormalities of blood vessels in the kidneys should be considered a possibility at any age for someone with NF1. In older people tumors known as pheochromocytomas, discussed in Chapter 7, may be the cause. Whenever someone with NF1 develops high blood pressure, it is wise to evaluate all the possible options before making a diagnosis. Treatment depends on the underlying cause. Essential hypertension in NF1 is probably caused by the same factors that contribute to high blood pressure in the general population. Risk factors include age, excessive weight, diets high in salt, and lack of regular exercise. The current recommendations for target blood pressure for people with NF1 are the same as in the general population. People who have prehypertension should make lifestyle changes to prevent developing high blood pressure. Those who already have hypertension should try to lower their blood pressure readings to less than 140/90 mm Hg. Those who have hypertension and diabetes or chronic kidney disease2 should aim for less than 130/80 mm Hg. Lifestyle strategies to reduce blood pressure to healthy levels include weight loss; moderate exercise; a diet that includes more fruits, vegetables, whole grains, and low-fat dairy foods; and reduced intake of alcohol and salt. Several medications are available to reduce high blood pressure in those people who cannot lower it by following diet and exercise regimens. Consult a physician for a personal recommendation. Renovascular abnormalities occur in ~1 in 100 people with NF1 and include several conditions that can affect blood pressure.3 The most common is renal artery stenosis, a constriction of one of the major blood vessels that transport blood to the kidneys. When blood flow is reduced, the kidney produces excess amounts of a hormone known as chymosin, triggering the release of other chemicals that raise blood pressure. Less often, an aneurysm—a bulging of a renal blood vessel—may develop in someone with NF1, or other types of abnormalities may develop in blood vessels contained within the kidney itself. To complicate matters, any renovascular abnormality may be part of a more extensive condition known as vasculopathy, an impairment of blood vessels that can occur anywhere in the body, usually because a proliferative lesion develops in the artery wall. The exact nature of this lesion and how it arises remain unknown. For instance, people who develop renal artery stenosis are also more likely to suffer from abdominal aortic coarctation, a narrowing of the abdominal portion of the body’s major blood vessel. If a renovascular abnormality is suspected, the precise type of disorder can be diagnosed with a combination of blood tests and imaging techniques, such as an ultrasound (which uses sound waves to generate an image), angiography or arteriography (which use radiopaque dyes), and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI, which uses a powerful magnet and computers). The tests ordered depend on the suspected complication. For renal artery stenosis, renal arteriography is the imaging modality of choice, with MRI as an alternative for people who have impaired kidney function or who cannot tolerate arteriography. Treatment depends on the diagnosis. Some people with NF1 who develop hypertension because of abnormalities in the renal arteries respond to the blood pressure medications described earlier. Others may require surgery. Several surgical options exist for the most common condition, renal artery stenosis. Often the first method used is angioplasty, a procedure in which a balloon-tipped catheter (a flexible narrow tube) is inserted into a narrowed artery. The balloon is then expanded so that the artery widens enough to allow normal blood flow. This procedure is often less successful at treating renal artery stenosis in people with NF1 than the general population.4 In NF1 the artery may have narrowed because of a proliferative lesion rather than the accumulation of plaque that is more readily cleared by angioplasty. If further treatment is necessary, one option is surgical revascularization, in which blood vessels harvested from somewhere else in the body are grafted onto the kidney to restore blood flow. Another is nephrectomy, removal of the kidney—generally reserved for people with severe disease or those who have failed to respond to other treatments. People with NF1 are more likely than the general population to be born with congenital heart defects. Estimates about the number of people with NF1 who have this condition vary from less than 1% to more than 6%, but the number is probably closer to ~2%.5 This is at least twice as often as heart defects occur in the general population, where estimates of prevalence vary from 0.4 to 0.9%.6 Studies in mice suggest that the protein product of the NF1 gene, neurofibromin, is important for prenatal development of the heart, although the precise mechanism remains unknown.7,8 Pulmonary stenosis, a constriction of the arteries that pump deoxygenated blood from the heart to the lungs, is the type of congenital heart defect seen most frequently in people with NF1. In this population, this condition accounts for one in four cases of congenital heart disease.5 Another congenital anomaly of the heart commonly seen in NF1 is coarctation or narrowing of the aorta, the body’s largest blood vessel. The aorta transports oxygenated blood from the heart to arteries extending throughout the body. Diagnosis of a congenital heart defect is made on the basis of physical examination and medical tests. Physical examination of any person diagnosed with NF1 should include a careful assessment of heart function, including blood pressure reading and auscultation, the use of a stethoscope to hear sounds made by the heart. If a heart murmur is detected, the patient should be referred to a cardiologist for further evaluation and testing, including an echocardiogram. This test uses sound waves to provide a picture of the heart as it beats as well as information about valve function and muscle health. This helps to determine whether the abnormality is pulmonary stenosis, aortic coarctation, or another type of heart defect. When aortic coarctation is suspected, blood pressure measurements should be taken in all four extremities (arms and legs) to determine the extent and effect of the narrowed aorta. Further evaluation and treatment options depend on the defect and age of the person. The vascular system consists of blood vessels that help oxygenated blood circulate throughout the body and then return to the heart for reoxygenation. In some people with NF1, blood vessels may become constricted, blocked, or damaged—a condition known as vasculopathy. These events may occur in any blood vessel, and usually multiple blood vessels are involved. The changes include narrowing (stenosis), blockage (occlusion), or a circumscribed bulging of a blood vessel (aneurysm). In rare but severe cases, a vessel may rupture, causing internal hemorrhage. Most people with NF1 who have vasculopathy do not experience symptoms; for that reason, it is unclear how many people with the disorder have this complication. Symptoms are most likely to develop in people with renal artery abnormalities or cerebrovascular abnormalities of blood vessels in the brain. Cerebrovascular anomalies are not common in people with NF1. When they do occur, most often the carotid artery, a major blood vessel at the base of the brain, is narrowed or obstructed. Smaller vessels will sprout around the blocked artery as the body seeks to compensate for the sudden reduction of blood flow to the area, creating a condition known as “moyamoya” (Fig. 9–1). Moyamoya is more common in children with NF1 who undergo cranial radiation for treatment of a brain tumor because radiation can damage blood vessels. Surgical procedures to redirect blood flow around the obstruction are available to individuals with moyamoya. Other types of cerebrovascular abnormalities include aneurysms and malformation of blood vessels in the brain. Figure 9–1 An angiogram demonstrating moyamoya syndrome in a child with NF1. The condition occurs when a blood vessel becomes blocked and smaller collateral blood vessels form in the surrounding area. If a cerebrovascular abnormality is detected, treatment is the same as in the general population. An initial strategy may include medications such as aspirin and blood thinners to prevent blood clots from forming in narrowed arteries. In other cases brain surgery may be necessary to remove obstructions or prevent vessels from rupturing. NF1 may alter height and bone development in a variety of ways. It is unclear why. Fortunately, when orthopedic involvement occurs, early detection can prevent or minimize functional impairment and skeletal deformity. Severe skeletal deformities are rare, although they are often the ones that are pictured in medical textbooks. Because signs of orthopedic changes may be subtle at first, a child diagnosed with NF1 should receive regular orthopedic examinations until early adulthood (see Chapter 5). The most frequent types of skeletal manifestations associated with NF1 are described briefly below. The spinal column (Fig. 9–2) consists of 33 bones called vertebrae that extend from the base of the skull to the pelvis. The spine surrounds and protects the spinal cord, the network of nerves that connect the brain to the peripheral nervous system. Each peripheral nerve is rooted in the spinal cord and then extends a series of nerve branches outward to locations throughout the body. The cervical section is the topmost portion of the spine; the thoracic section is located at the rear wall of the chest and attached to the ribs; the lumbar section constitutes the lower back; the sacrum and coccyx consist of fused vertebrae in the pelvic area. NF1 can deform the spine in several ways. Figure 9–2 The regions of the spine. (Courtesy of Harriet Greenfield, with permission.) Curvature of the spine is the most common type of spinal distortion seen in people with NF1. A healthy spine, viewed from behind, runs straight up the middle of the back dividing the trunk into halves. In scoliosis, the spine curves and distorts the normal symmetry of the trunk. Depending on the severity of the curve, other abnormalities may be evident, such as uneven shoulder height, a pronounced pelvic tilt, or a larger space between arm and trunk on one side of the body when a person is standing. It is not known what causes scoliosis in people with NF1, just as it is not known what causes most cases in the general population. Contrary to what some people believe, scoliosis does not result from poor posture, back strain, or active sports. Scoliosis is found in less than 1% of men and ~2% of women in the general population,9 but in people with NF1, it presents in 10%.10(p262) Children with NF1 tend to develop scoliosis earlier than other children, usually by 10 years of age,11 underscoring the need for regular physical examinations. Sometimes scoliosis is so mild that it does not require treatment. To prevent potentially serious developments, however, any child with NF1 should be examined for scoliosis annually as part of a comprehensive physical examination (see Chapter 5). Once scoliosis is diagnosed, the child should be reexamined regularly to determine whether the curve is progressing. The most common type of scoliosis in NF1 involves a type of curve indistinguishable from that seen in the general population: a gentle lateral curve in the shape of a C that involves about one third of the spine (Fig. 9–3). Any portion of the spine may be susceptible, although people with NF1 often develop a curvature in the lower cervical and upper thoracic spine, sometimes accompanied by kyphosis, a hump. Management of this type of scoliosis is similar to that in the general population and depends on a combination of factors: the degree of curvature, its location and rate of progression, and the age of the child. Curves located in the thoracic portion of the spine are more likely to progress than are lumbar curves. Because a curve is most likely to progress while the child is actively growing, any curve that is already significant before adolescence may progress further during the growth spurts associated with puberty. Management options for this most common form of scoliosis in NF1 are many, but generally fall into three broad categories: monitoring without intervention, bracing, or surgery.

Other Features of Neurofibromatosis 1

♦ Cardiovascular Complications

Hypertension

Congenital Heart Defects

Vasculopathy

♦ Orthopedic Manifestations

Spinal Problems

Scoliosis

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree