The following overview of nonepileptic paroxysmal disorders is organized by age, type, and time of occurrence. Psychogenic nonepileptic seizures are discussed in Chapter 40.

INFANCY

Sleep

During infancy, at least two paroxysmal behaviors may be confused with seizures: repetitive episodes of head banging while the infant is falling asleep and benign neonatal myoclonus usually occurring during sleep.

Head Banging (Rhythmic Movement Disorder)

Rhythmic movement disorders, such as repetitive motion of the head, trunk, or extremities, usually occur as a parasomnia during the transition from wakefulness to sleep or from sustained sleep (9). Head banging can last from 15 to 30 minutes as the infant drifts off to sleep and, unlike similar daytime activity, is usually not related to emotional disturbance, frustration, or anger. No abnormal electroencephalographic (EEG) findings are noted. These benign movements usually disappear within 1 year of onset, typically by the second or third year of life, without treatment (7,9).

Benign Neonatal Myoclonus

Rapid and forceful myoclonic movements may involve one extremity or many parts of the body. Occurring during sleep in early infancy, these bilateral, asynchronous, and asymmetric movements usually migrate from one muscle group to another. Unlike seizures, their rhythmic jerking is not prolonged, although clusters of these movements may occur episodically during all stages of sleep. Attacks are usually only a few minutes long but may last up to hours. Myoclonus is not stimulus sensitive, and EEG shows no epileptiform activity. The movements stop as the infant is awakened and should never be seen in a fully awake and alert state. No treatment is required, but clonazepam or other benzodiazepines have been suggested in children who demonstrate a large amount of benign myoclonic activity. The movements typically disappear over several months (10).

Wakefulness

Jitteriness

Neonates and young infants demonstrate this rapid generalized tremulousness, which in neonates may be severe enough to be mistaken for clonic seizures. The infants are alert, and the movements may be decreased by passive flexion or repositioning of the extremities. Although jitteriness may occur spontaneously, it is typically provoked or increased by stimulation. Because neonatal jitteriness may be caused by certain pathologic states, jittery newborns are more likely than normal infants to experience seizures, and their EEG tracings may show abnormalities. Central nervous system dysfunction is the suspected etiology, but hypoxic–ischemic insults, metabolic encephalopathies such as hypoglycemia and hypocalcemia, drug intoxication or withdrawal, and intracranial hemorrhage may play a role and should be ruled out, if symptoms persist. The more benign forms of jitteriness usually decrease without specific therapy. Prognosis depends on the etiology and in neonates with severe, prolonged jitteriness may be guarded. Nevertheless, in 38 full-term infants who were jittery after 6 weeks of age, the movements resolved at a mean age of 7.2 months; 92% had normal findings on neurodevelopmental examinations at age 3 years (11). Sedative agents may be used, but their adverse effects usually increase the irritability (11,12).

Head Banging or Rolling and Body Rocking

Head banging, head rolling, and body rocking often occur in awake infants (7). In older infants, head banging may be part of a temper tantrum. Head rolling and body rocking seemingly are pleasurable forms of self-stimulation and may be related to infantile masturbation. If the infants are touched or their attention is diverted, the repetitive movements cease. They are more common in irritable, excessively active, cognitively challenged infants (7). Nevertheless, most of this activity decreases during the second year. Particularly, bothersome movements may be diminished by behavior modification techniques, but drug treatment usually is unnecessary.

Infantile Gratification Behavior (Infantile Masturbation)

Gratification behavior or infantile masturbation is a form of self-stimulation in infancy (13,14). Infantile masturbation is part of the normal sexual human development. It may mimic abdominal pain, seizures, or dyskinesias. Although infantile masturbation has been typically described in infant girls, it is also present in boys, but due to cultural reasons, episodes in boys may not be brought to the attention of health professionals.

The typical description of the events includes sitting with the legs held tightly together or straddle the bars of the crib or playpen or other toys and rock back and forth. Distracting stimuli usually stop these movements, but some children become irritable when interrupted. Events typically disappear over the period of several months. Masturbation in older children is less likely to be confused with seizure activity. In some cognitively impaired children with autism, self-stimulation can also be associated with a fugue state. Because these children are difficult to arouse during the activity, seizures are commonly suspected (15). Once the diagnosis is made, parents may be taken aback by the terminology due to social stigma associated with the term masturbation. We therefore offer gratification behavior as an alternative diagnostic term that may be accepted more easily by families.

Benign Myoclonus of Early Infancy

These myoclonic movements occur in children during wakefulness state and may resemble infantile spasms but are not associated with EEG abnormalities. Infants are usually healthy, with no evidence of neurologic deterioration. The myoclonic episodes abate without treatment after a few months (16).

Spasmodic Torticollis

Spasmodic torticollis is a disorder characterized by sudden, repetitive episodes of head tilting or turning to one side with rotation of the face to the opposite side. The episodes may last from minutes to days. During episodes, children are irritable and uncomfortable but alert and responsive. Although movements may present in a recurrent and episodic pattern, EEG findings remain normal. Nystagmus is not associated with this disorder. The etiology is unknown, although dystonia and labyrinthine imbalance have been proposed. A family history of torticollis or migraine may be present. Similar tonic or head, neck, and body rotary movements may also be seen with gastroesophageal reflux (Sandifer syndrome), but these usually last longer than spasmodic torticollis (17–20).

The differential diagnosis includes congenital, inflammatory, and neoplastic conditions of the posterior fossa, cervical cord, spine, and neck. During these conditions, the episodes of torticollis are sustained and lack the usual on-and-off variability. An evaluation is necessary, but spasmodic torticollis usually subsides without treatment during the first few years of life.

Spasmus Nutans

Head nodding, head tilt, and nystagmus comprise spasmus nutans. Head nodding or intermittent nystagmus (or both) is usually noted at 4 to 12 months of age. Interestingly, nystagmus may be more prominent in one eye. The symptoms can vary depending on position, direction of gaze, and time of day. The children are clinically alert, and although symptoms may fluctuate throughout the day, episodic alterations in level of consciousness do not occur. Spasmus nutans usually remits spontaneously within 1 or 2 years after onset but may last as long as 8 years. Minor EEG abnormalities may be noted, but classic epileptiform discharges are not associated. Because mass lesions of the optic chiasm or third ventricle have been noted in a small proportion of these infants, computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging studies are usually recommended. It is difficult to distinguish eye movements persisting into later childhood or adulthood from congenital nystagmus (21–23).

Opsoclonus

Opsoclonus is a rare abnormality characterized by rapid, conjugate, multidirectional, oscillating eye movements that are usually continuous but may vary in intensity. Because of this variation and occasionally associated myoclonic movements, generalized or partial seizures may be suspected. The children remain responsive and alert. Opsoclonus usually implies a neurologic disorder such as ataxia myoclonus or myoclonus. Children who develop these signs early in life may have a paraneoplastic syndrome caused by an underlying neuroblastoma (24–26). The triad of opsoclonus, myoclonus, and encephalopathy is termed Kinsbourne encephalopathy (dancing eyes, dancing feet) and responds to removal of the neural crest tumor or treatment with corticosteroids or corticotropin (27). Other forms of episodic ataxia in association with nystagmus may be seen in later infancy and childhood, but rarely true opsoclonus (8).

Rumination

Rumination attacks involve hyperextension of the neck, repetitive swallowing, and protrusion of the tongue. Episodes are thought to be related to abnormal esophageal peristalsis and typically follow or accompany feeding. The child is alert but sometimes seems distressed and uncomfortable. Variable feeding techniques are helpful in this disorder, which resolves as the child matures (28).

Startle Disease or Hyperekplexia

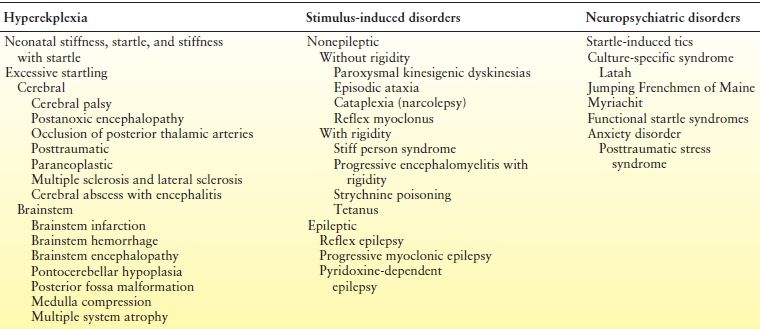

Hyperekplexia together with stimulus-induced disorders and neuropsychiatric startle syndrome are part of the startle syndromes (Table 41.2) (29). Hyperekplexia is a rare familial disorder with autosomal dominant or autosomal recessive inheritance, but some cases are sporadic (29,30). At least five genes have been described in the context of hyperekplexia to date, and over 80% have been linked to mutations of the alpha subunit of the glycine receptor (GLRA1). Other genes include GLRB, SLC6A5, GPHN, and ARHGEF9, while frequently no mutation can be found (30).

Table 41.2 Differential Diagnosis of Three Groups of Startle Syndromes

Modified from Bakker MJ, van Dijk JG, van den Maadenberg AM, et al. Startle syndromes. Lancet Neurol. 2006;5:513–524.

In the past, any type of exaggerated startle response was labeled hyperekplexia. It has now become clear that many of these cases may simply represent an augmented normal startle reflex (31), and we therefore reserve the term hyperekplexia for patients presenting with the three main clinical symptoms of generalized stiffness (hypertonia), excessive startle beginning at birth and a short period of generalized stiffness following the startle reflex (32). Hyperekplexia may lead to falls. Clinically, the infant becomes stiff when handled, and episodes of severe hypertonia may also present with apnea and bradycardia. At times, forced flexion of the neck or hips may interrupt episodes. Also noted, along with transient hypertonia, are falling attacks without loss of consciousness, ataxia, generalized hyperreflexia, episodic shaking of the limbs resembling clonus, and excessive startle. While the interictal electroencephalogram is normal, a spike may be associated with a startle attack. Whether this discharge represents an evoked response to the stimulus or an artifact is a subject of debate. The disorder must be distinguished from so-called startle epilepsy, in which a startle is followed by a partial or generalized seizure, which suggests a defect in inhibitory regulation of brainstem centers (33,34). The prognosis in hyperekplexia is variable (31). Seizures do not develop after this benign disorder. However, clonazepam and valproic acid have been used to treat associated startles, stiffness, jerking, and falling (35,36).

Shuddering Attacks

Shuddering attacks far exceed the normal shivering frequently seen in older infants and children. A very rapid tremor involves the head, arms, trunk, and even the legs; the upper extremities are adducted and flexed at the elbows or, less often, adducted and extended. The episodes may begin as early as 4 months of age and decrease gradually in frequency and intensity before age 10 years. Treatment with antiepileptic drugs does not modify the attacks. Except for movement artifact, results of electroencephalography are normal. While earlier reports linked shuddering attacks with early manifestations of essential tremor (37,38), findings could not be confirmed in a more recent series (39).

Alternating Hemiplegia

Alternating hemiplegia of childhood may be confused with epilepsy because of the paroxysmal episodes of weakness, hypertonicity, or dystonia. Presenting as tonic or dystonic events, these intermittent attacks may alternate from side to side and at times progress to quadriplegia. They usually occur at least monthly and may be part of a larger neurologic syndrome in children with delayed or retarded development who also have seizures, ataxia, and choreoathetosis. Attacks begin before 18 months of age and can be precipitated by emotional factors or fatigue. The hemiplegic episodes may last minutes or hours, and recent genetic studies linked the clinical presentation with the ATP1A3 gene, which encodes a Na+,K+-ATPase, an ion pump responsible for maintaining sodium and potassium electrochemical gradients across the plasma membrane (40). Although anticonvulsants and typical migraine treatments are unsuccessful, flunarizine, a calcium channel blocker (5 mg/kg/day), has been reported to reduce recurrences (41,42).

Paroxysmal Tonic Upgaze

Age of onset of paroxysmal tonic upgaze is within the first year of life, with the earliest cases described at age 2 weeks, but some cases are detected during the preschool years. Episodes are described as upward, and tonic deviation of the eyes as a single symptoms or eye movement can be associated with altered movement coordination or ataxia. Events are typically brief but occasionally can last up to 30 minutes. The frequency of the events ranges from rare episodes to daily leading to consider the diagnosis of epileptic seizures. There is a predilection for boys. Neurologic assessment may be normal or may reveal hypotonia and developmental delays. Prognosis is benign with complete improvement of the symptoms before age 2 years in most cases (43).

Respiratory Derangements and Syncope

Primary breathing disorders usually occur without associated epilepsy. At times, however, respiratory symptoms may be confused with epilepsy, or, rarely, tonic stiffening, clonic jerks, or seizures may follow primary apnea (44). An electroencephalogram or polysomnogram recorded during the event may easily distinguish a respiratory abnormality associated with true seizures from one completely independent of epilepsy.

Infant Apnea or Apparent Life-Threatening Events

Apnea usually occurs during sleep and may be associated with centrally mediated hypoventilation, airway obstruction, aspiration, or congenital hypoventilation. Formerly called (near) sudden infant death syndrome, these symptoms have now been termed apparent life-threatening events. During central apnea, chest and abdominal movements decrease simultaneously with a drop in airflow. During obstructive apnea, movements of the chest or abdomen (or both) continue, but there is diminished air flow. Central apnea presumably results from a disturbance of the respiratory centers, whereas obstructive apnea is related to a peripheral blockage of airflow. Some infants may also have a mixed form of the disorder. A few jerks may occur with the apneic episodes but do not represent epileptic myoclonus. The apnea that follows a seizure is a form of central apnea with postictal hypoventilation. Primary apnea, however, is only rarely followed by seizures (45,46).

The etiology and characteristics of apneic episodes vary among infants. Apnea of prematurity responds to treatment with xanthine derivatives. In older infants with primary central apnea, elevated cerebrospinal fluid levels of β-endorphin have been reported, and treatment with the opioid antagonist naltrexone has been successful (47). The role of home cardiopulmonary monitors is controversial. Parents should be encouraged to follow the recommendations of the American Academy of Pediatrics that healthy term infants be put to sleep on their back or side to decrease the risk of apnea and possible sudden infant death syndrome (48).

Although apnea occurs less often when the child is fully awake, it may be associated with gastroesophageal reflux (49,50). Aspiration may follow. Reflux is frequently accompanied by staring, flailing movements of the extremities or posturing of the trunk, possibly in response to the pain of acidic contents washing back into the esophagus. Gastroesophageal reflux is more common when infants are laid supine after feeding. Diagnosis is established by radiologic demonstration of reflux or by abnormal esophageal pH levels. Reflux is treated by upright positioning of the baby during and after feeding (51), thickened feedings, and the use of agents to alter sphincter tone and, in infants who do not respond to medical treatment, very rarely, Nissen fundoplication.

Cyanotic Breath-Holding Spells

Although common between the ages of 6 months and 6 years, cyanotic infant syncope (breath-holding spells) is frequently confused with tonic seizures (52). Typically precipitated by fear, frustration, or minor injury, the spells involve vigorous crying, following which the child stops breathing, often in expiration. Cyanosis occurs within several seconds, followed by loss of consciousness, limpness, and falling. Prolonged hypoxia may cause tonic stiffening or brief clonic jerking of the body. After 1 or 2 minutes of unresponsiveness, consciousness returns quickly, although the infant may be briefly tired or irritable. The crucial diagnostic point is the history of an external event, however minor, precipitating the episode. The electroencephalogram does not show interictal epileptiform discharges but may reveal slowing or suppression during the anoxic event. The pathophysiologic mechanism is not well understood, but correction of any underlying anemia may reduce the attacks (53). Children with pallid breath-holding spells have autonomic dysregulation caused by parasympathetic disturbance distinct from that found in cyanotic breath-holding (54). Although the episodes appear unpleasant for the child, they do not result in neurologic damage. Antiepileptic medication may be appropriate for the rare patients with frequent postsyncopal generalized tonic–clonic seizures triggered by the anoxia.

Pallid Syncope

Precipitated by injury or fright, sometimes trivial, pallid infant syncope occurs in response to transient cardiac asystole in infants with a hypersensitive cardioinhibitory reflex. Minimal crying, perhaps only a gasp, and no obvious apnea precede loss of consciousness. The child collapses limply and subsequently may have posturing or clonic movements before regaining consciousness after a few minutes (52,55–57). The asystolic episodes may be reproduced by ocular compression, but this procedure is risky and of uncertain clinical utility as it may lead to iatrogenic prolonged asystole and cardiac arrest. As with cyanotic breath-holding spells, the key to diagnosis is the association with precipitating events.

The long-term prognosis is benign. Most children require no treatment, although atropine has been recommended for frequent pallid attacks or those followed by generalized tonic–clonic seizures (58). A trial of the anticholinergic drug atropine sulfate 0.01 mg/kg every 24 hours in divided doses (maximum 0.4 mg/day) may increase heart rate by blocking vagal input. Atropine should not be prescribed during very hot weather because hyperpyrexia may occur.

CHILDREN

Sleep

Myoclonus

Nocturnal myoclonic movements, called “sleep starts” or “hypnic jerks” and associated with a sensation of falling, are less common in older children and adolescents than in infants (10). The subtle involuntary jerks of the extremities or the entire body occur while the child is falling asleep or being aroused. Repetitive rhythmic jerking is uncommon, although several series of jerks can occur during the night. The jerks are not associated with epileptiform activity, but a sensory-evoked response or evidence of arousal may be present on the electroencephalogram (59–62).

Periodic repetitive movements that resemble myoclonus are seen in deeper stages of sleep and may arouse the patient so that daytime drowsiness is noted. These movements are more common in rapid eye movement (REM) than in non–rapid eye movement (NREM) sleep and are clearly distinguished from epilepsy on sleep polysomnographic recordings. In very severe cases, a treatment trial with benzodiazepine may be helpful.

Hypnagogic Paroxysmal Dystonia

In hypnagogic paroxysmal dystonia, an extremely rare disorder, sleep may be briefly interrupted by seemingly severe dystonic movements of the limbs lasting a few minutes. Episodes are sometimes accompanied by prolonged vocalization. No EEG abnormality is noted. Carbamazepine may decrease the attacks. It is not clear whether some or all patients with this clinical syndrome actually have seizures arising from the supplementary motor area (60,63).

Nightmares

Nightmares occur during REM sleep and are rarely confused with seizures. Although children may be restless during the dream, they usually do not scream out, sit up, or have the marked motor symptoms, autonomic activity, and extreme sorrow seen with night terrors. Incontinence may be present, however. Remembrance of the content of nightmares may lead to a fear of sleeping alone. An electroencephalogram recorded during these events shows no abnormalities (7).

Night Terrors (Pavor Nocturnus)

Night terrors, most common in children between the ages of 5 and 12 years, begin from 30 minutes to several hours after sleep onset, usually during NREM slow-wave sleep or sleep stage N3 according to the American Academy of Sleep Medicine terminology. Diaphoretic and with dilated pupils, the children sit up in bed, crying or screaming inconsolably for several minutes before calming down. Sleep resumes after the attack, and children do not recall the event. No treatment is recommended (64,65).

Sleepwalking

Approximately 15% of all children experience at least one episode of sleepwalking or somnambulism, which usually occurs 1 to 3 hours after sleep onset (NREM slow-wave sleep or sleep stage N3). The etiology is unknown, but a familial prevalence is noted. Mumbling and sleeptalking, the child walks about in a trance and returns to bed. Semipurposeful activity such as dressing, opening doors, eating, and touching objects during an episode of somnambulism may be confused with automatisms of complex partial seizures. The eyes are open, and the child rarely walks into objects. Amnesia follows, and no violence occurs during the event. Treatment is usually not required, except for protecting the wandering child from injuries during the night. Benzodiazepine therapy may be helpful in frequent or prolonged attacks (3,66,67).

Wakefulness

Myoclonus

In many normal, awake children, anxiety or exercise may cause an occasional isolated myoclonic jerk. Treatment is rarely necessary.

Multifocal myoclonus may occur in patients with progressive degenerative diseases or during an acute encephalopathy. It may be difficult to distinguish these movements from chorea, and these two disorders may coexist in some encephalopathic illnesses. Myoclonus persists in sleep, whereas chorea usually disappears during sleep (7).

Chorea

Usually seen as rapid jerks of the distal portions of the extremities, choreiform movements may affect muscles of the face, tongue, and proximal portions of the extremities. When associated with athetosis, chorea involves slower, more writhing movements of distal portions of the extremities. The jerks may be so fluid or continuous that they are camouflaged. Acute chorea may accompany metabolic disorders but is more likely in patients recovering from illnesses such as encephalitis. Other causes are Sydenham chorea seen in the setting of β-hemolytic streptococcal infection, drug ingestion, and mass lesions or stroke involving the basal ganglia. Treatment depends primarily on the etiology, but movements may respond to haloperidol or a benzodiazepine such as clonazepam (68,69).

Tics

Like chorea, most tics are present during wakefulness and disappear with sleep. They usually involve one or more muscle groups, are stereotyped and repetitive, and appear suddenly and intermittently. Movements may be simple or complex, rhythmic, or irregular. Facial twitches, head shaking, eye blinking, sniffling, throat clearing, and shoulder shrugging are typical, although more complex facial distortions, arm swaying, and jumping have been noted. These purposeless movements cannot be completely controlled, but they may be inhibited voluntarily for brief periods and are frequently exacerbated by stress or startle (70–72).

In Tourette syndrome, complex vocal and motor tics are frequently associated with learning disabilities, hyperactivity, attention deficits, and compulsive behaviors. The incidence of simple and complex tics is high in relatives of these patients. The disorder varies in severity but tends to be lifelong, although it may stabilize or improve slightly in adolescence or early adulthood. Combinations of behavior therapy and medical treatment of tics and compulsive behavior are indicated. Haloperidol, pimozide, and clonidine have been used successfully for behavior control. Stimulants such as methylphenidate may initially exacerbate tics (70–72).

Paroxysmal Dyskinesias

Paroxysmal dyskinesias are rare disorders characterized by repetitive episodes of relatively severe dystonia or choreoathetosis (or both). Multiple brief attacks occur daily, precipitated by startle, stress, movement, or arousal from sleep (73). Consciousness is preserved, but discomfort is evident. Both sporadic and familial types have been described. Kinesigenic dyskinesia frequently is associated with the onset of movement as well as with prior hypoxic injury, hypoglycemia, and thyrotoxicosis. Alcohol, caffeine, excitement, stress, and fatigue may exacerbate attacks of paroxysmal dystonic choreoathetosis, a familial form of the disorder. Although the electroencephalogram displays normal findings during the episodes, the paroxysmal dystonic form responds to antiepileptic drugs such as carbamazepine (73–76).

Stereotypic Movements

Other repetitive movements have been mistaken for seizures, especially in neurologically impaired children. Stereotypy is seen in individuals with autism, sensory disabilities, intellectual disabilities, or developmental disabilities (77–79).

Donat and Wright (80) noted head shaking and nodding, lateral and vertical nystagmus, staring, tongue thrusting, chewing movements, periodic hyperventilation, tonic posturing, tics, and excessive startle reactions in these patients, many of whom had been treated unnecessarily for epilepsy.

A behavior is defined as stereotypy when “involves repetition, rigidity and invariance, as well as a tendency to be inappropriate in nature” (81). The stereotypical behaviors may be verbal or nonverbal and involve fine or gross motor movements or simple and complex movements. Behaviors can occur with and without objects (77). Some stereotypies can involve self injurious behavior (78). Other common example of stereotypies include hand flapping, body rocking, toe walking, spinning objects, sniffing, immediate and delayed echolalia, and running objects across one’s peripheral vision (77). Self-stimulatory behaviors such as rhythmic hand shaking, body rocking, and head swaying, performed during apparent unawareness of surroundings, also are common in cognitively impaired children with specific neurologic diagnoses. Rett syndrome should be suspected when repetitive “hand-washing” movements are noted in retarded girls (70). Deaf or blind children frequently resort to self-stimulation such as hitting their ears or poking at their eyes or ears, which has been misidentified as epilepsy. Behavior training is frequently more successful than medication in controlling these movements (80).

Head Nodding

Head nodding or head drops may be of epileptic or nonepileptic origin. A study by Brunquell et al. (82) showed that epileptic head drops were associated with ictal changes in facial expression and subtle myoclonic extremity movements. Rapid drops followed by slow recovery indicated seizures. When the recovery and drop phases were of similar velocity or when repetitive head bobbing occurred, nonepileptic conditions were much more common.

Staring Spells

When ordinary daydreaming or inattentive periods are repetitive and children do not respond to tactile or auditory stimulation being called, the behaviors may be classified as absence (petit mal) seizures. During innocent daydreaming, posture is maintained and automatisms do not occur. Staring spells are usually nonepileptic in normal children with normal EEG findings, when parents report preserved responsiveness to touch, body rocking, or identification without limb twitches, upward eye movements, interrupted play, or urinary incontinence (83). Children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder sometimes have staring spells that resemble absence or complex partial seizures. Although unresponsive to verbal stimuli, these children generally become alert immediately on being touched and frequently recall what was said during the staring spell. During these spells, the electroencephalogram pattern is normal. Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder affects 3% to 10% of children and has a male predominance. Stimulants are most widely used, but other medications may be necessary to ameliorate behavior in refractory cases. Antiepileptic drugs are usually ineffective (60,84–87).

Headaches

Recurrent headaches are rarely the sole manifestation of seizures. However, postictal headaches are not uncommon, especially following a generalized convulsion. Headaches may also precede seizures. As an isolated ictal symptom, headache occurs most frequently in children with complex partial seizures (88). Children with ictal headaches experience sudden diffuse pain, often have a history of cerebral injury, derive no relief from sleep, and lack a family history of migraine. Distinguishing headache from paroxysmal recurrent migraine may be difficult in young children when the headache’s throbbing unilateral nature is absent or not readily apparent. Migraine, however, is more prevalent than epilepsy. In addition, ictal electroencephalograms during migraine usually show slowing, whereas those during epilepsy demonstrate a clear paroxysmal change. Associated gastrointestinal disturbance and a strong family history of migraine help establish the appropriate diagnosis (88–94).

Epilepsy and migraine can coexist. Children with migraine have a 3% to 7% incidence of epilepsy, and as many as 20% exhibit epileptiform discharges on interictal electroencephalograms (91). Up to 60% of children with migraine obtain significant relief with antiepileptic medication (93,94). Other variants of migraine that may be confused with seizures include cyclic vomiting (abdominal pain), acute confusional states, and benign paroxysmal vertigo.

Recurrent Abdominal Pain

Recurrent abdominal pain may be associated with vomiting, pallor, or even fever and has been noted in migraine and epilepsy. Usually, these complaints indicate neither diagnosis, although some children with recurrent abdominal pain or vomiting may experience migraine later in life (7,95). About 7% to 76% of children with recurrent abdominal pain exhibit interictal paroxysmal EEG changes. Approximately 15% of these patients have a diagnosis of seizures, and more than 40% have recurrent headaches (7). A family history of migraine is found in approximately 20% (94). Although most of these children do not respond to antiepileptic drugs, approximately 20% obtain relief from antimigraine medications such as β-blockers or tricyclic antidepressants (7,91,95).

Confusional Migraine

Migraine may present in an unusual and sometimes bizarre fashion as confusion, hyperactivity, partial or total amnesia, disorientation, impaired responsiveness, lethargy, and vomiting (96). These episodes must be distinguished from toxic or metabolic encephalopathy, encephalitis, acute psychosis, head trauma, and sepsis as well as from an ictal or postictal confusional state. Confusional migraine usually persists for several hours, less commonly for days, and spontaneously clears following sleep. The diagnosis is usually made following the episode when the patient or family reports severe headache or visual symptoms heralding the onset of the event or a history of similar events. During and soon after the episodes, an electroencephalogram may demonstrate regional slowing, a nondiagnostic finding.

Benign Paroxysmal Vertigo

Benign paroxysmal vertigo consists of brief recurrent episodes of disequilibrium of variable duration that may be misinterpreted as seizures. Lasting from minutes to hours, the attacks of vertigo occur as often as two to three times per week but rarely as infrequently as every 2 to 3 months. Tinnitus, hearing loss, and brainstem signs have been implicated as causes, but the onset is sudden, and the child is usually unable to walk. Extreme distress and nausea are noted, but the patient remains alert and responsive during attacks. Nystagmus or torticollis is frequently observed. Between attacks, examination and electroencephalography reveal normal results. A minority of children show dysfunction on vestibular testing but show no abnormalities on audiograms. A family history of migraine is common, and most of these children experience migraines later in life. No treatment is indicated because the attacks do not respond well to either antiepileptic or antimigraine medications. Benign paroxysmal vertigo usually subsides by ages 6 to 8 years (60,97,98).

Stool-Withholding Activity and Constipation

Children may have sudden interruption of activity and assume a motionless posture with slight truncal flexion and leg stiffening when experiencing discomfort from withholding stool (99). The withholding behavior, which may be mistaken for absence or tonic seizures, evolves as a way to prevent the painful passage of stool that is large and hard because of chronic constipation. At times, stool withholding occurs in the setting of a painful anal fissure. Small jerks of the limbs may be misperceived as myoclonus, and the child may have fecal incontinence. The behavior resolves with treatment of the chronic constipation.

Rage Attacks

The episodic dyscontrol syndrome, or recurrent attacks of rage following minimal provocation, may be seen in children with or without epilepsy. The behavior often seems completely out of character. Rage may be more common in hyperactive children or those with conduct and personality disorders. Similar dyscontrol and near rage have been seen following head injury with frontal or temporal lobe lesions. Ictal rage is rare, unprovoked, and usually not directed toward an individual. Following attacks of rage and the appearance of near psychosis, the child resumes a normal state, may recall the episode, and feel remorseful. Behavior frequently can be modified during the event. Depending on the cause of the associated syndrome, β-blockers (100), stimulant drugs, and carbamazepine along with other antiepileptic drugs have been used to control outbursts (101).

Munchausen Syndrome by Proxy

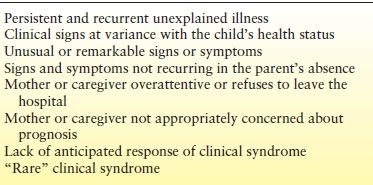

Munchausen syndrome, or factitious disorder, describes a consistent simulation of illness leading to unnecessary investigations and treatments. When a parent or caregiver pursues such a deception using a child, the situation is called Munchausen syndrome by proxy. Infants may be brought to child neurologists with parental reports suggesting apnea, seizures, or cyanosis; older children may be described to have episodes of loss of consciousness, convulsions, ataxia, headache, hyperactivity, chorea, weakness, gait difficulties, or paralysis. Accompanying symptoms may include gastrointestinal disorders or a history of unusual accidents and injuries that are poorly explained and almost never observed by anyone but the parent(s) (Table 41.3). Sometimes the child also becomes persuaded of the reality of the “illness” and develops independent factitious symptoms such as psychogenic seizures.

Table 41.3 Clinical Features of Munchausen Syndrome by Proxy

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree