INTRODUCTION

Traumatic and neoplastic disorders of the cervical spine attract surgical treatment. Infections are treated with antibiotics with or without surgical drainage, excision, and reconstruction. The two disorders of the cervical spine that attract pain management are neck pain and cervical radicular pain.

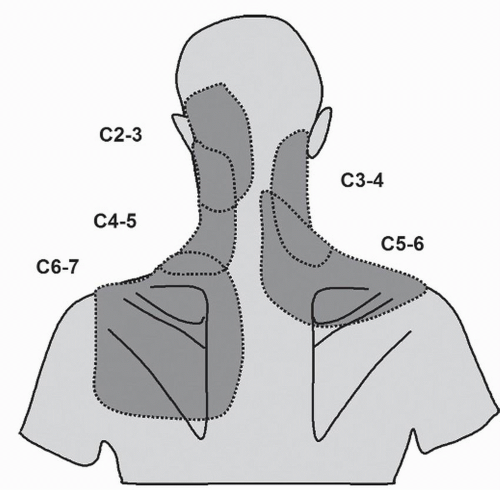

Neck pain is pain perceived dorsally over the cervical spine (

1). It implies a source in the muscles, ligaments, joints, or intervertebral disks of the cervical spine. Neck pain may be associated with somatic referred pain, which typically spreads from the cervical region into the upper limb girdle and proximal upper limb, where it is perceived in regions innervated by the same spinal cord segments that innervate the cervical source of pain. Several studies (

2,

3 and

4) have described the distribution of somatic referred pain from the cervical zygapophysial joints (

Fig. 19.1). Similar patterns apply for the cervical intervertebral disks (

5,

6 and

7). Anecdotally, somatic referred pain can spread into the forearm and hand, but this is unusual.

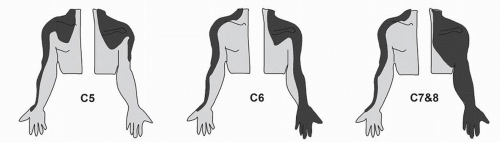

Cervical radicular pain is a different entity. It is caused by irritation of a cervical spinal nerve or its roots (

1). Although its source lies in the neck, cervical radicular pain is perceived in the upper limb. It spreads in bands, across the shoulder girdle, into the arm, and into the forearm and hand (

8). Although segmental, the distribution of radicular pain bears no resemblance, nor any relationship, to dermatomes (

Fig. 19.2). If anything, the distribution of pain is across the muscles, joints, and bones innervated by the affected nerve.

Cervical radiculopathy is yet another entity. It is defined by objective neurologic signs, such as numbness, weakness, paresthesia, and areflexia, in the segmental distribution of the affected spinal nerve (

1). Cervical radiculopathy may occur in association with cervical radicular pain, or either may occur in the absence of the other. No conservative therapy has been tested, let alone proven, to relieve the neurologic signs of cervical radiculopathy. That is the province of surgery. Such conservative treatments as have been applied have focused on radicular pain, not radiculopathy.

Both for neck pain and for cervical radicular pain, the types of pain management fall into three domains: multidisciplinary pain management, monotherapy, and interventional pain management. For each, the evidence base is distinctly different.

MUTLIDISCIPLINARY PAIN MANAGEMENT

Multidisciplinary pain management is widely advocated by pain clinics as the preferred form of care for spinal pain. However, it is difficult to find consistent or universally accepted definitions. To various extents, it involves medical assessment, physical therapy, psychological therapy, education, and social and vocational rehabilitation.

MONOTHERAPY

Monotherapies are treatments defined by a unique mechanism or distinctive mode of application. They include drug treatment, physical therapies, acupuncture, traction, and other interventions. They can be provided in isolation, by a practitioner who provides only that treatment, for example, acupuncture. They can be provided simultaneously in combinations, such as cervical mobilization coupled with exercises. They can be provided serially, such that when one fails to work, another is used, and can be provided by different therapists or by the same therapist.

INTERVENTIONAL PAIN MEDICINE

Interventional pain medicine is the application of invasive, but minor, procedures for the treatment of pain. It encompasses diagnostic blocks, therapeutic injections, and percutaneous procedures, often performed under fluoroscopic guidance, but not always.