Pain Mechanisms: Relevant Anatomy, Pathogenesis, and Clinical Implications

Beth A. Winkelstein

Nadine Dunk

James N. Weinstein

This chapter describes briefly the anatomy of the cervical spine and relevant potential sources of pain. It also presents several working hypotheses in the field describing the mechanisms of pain symptom development and maintenance. In an effort to present these concepts, we review the relevant anatomy of the cervical spine with a specific focus on the structures with the potential for initiating pain with relevance to their injury. Then, a brief discussion reviews the neuronal and neuroimmune mechanisms of physiologic and persistent pain. The neurophysiology of pain highlights traditional concepts of injury and pain processing, as well as more recent hypotheses of the central nervous system’s (CNS’s) neuroimmunologic involvement in persistent pain. The third section of this chapter discusses considerations for common painful mechanical injury to specific components of the cervical spine: the facet joint and nerve root. Lastly, a discussion of clinical implications and suggested areas of future work is presented.

ANATOMY

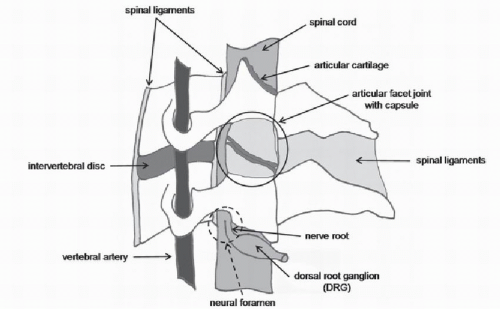

Many anatomical structures of the cervical spine have the potential to generate pain. These same structures, by virtue of their biomechanical and/or physiologic functions, are also important in a variety of neck injuries and pathologies leading to neck pain syndromes (Fig. 8.1). Anatomical sources with the potential to generate pain include both hard and soft tissue components, such as the ligaments, intervertebral disk, facet joints, and muscles, among others. Nociceptors have been demonstrated in all of these tissues, supporting their ability to generate pain when such pain nerve fibers are activated. Equally relevant to the initiation and maintenance of pain are the neural components of the spine, as they can be injured directly during many loading scenarios for the neck.

HARD AND SOFT TISSUES

The cervical spine is composed of bony vertebrae, which are connected by the intervertebral disk, ligaments, and other soft tissues that extend across single and multiple vertebral levels (Fig. 8.1). The vertebrae articulate with each other via the disks in the anterior column and the bilateral facet joints. Since the anatomy of the cervical spine is covered in an earlier chapter, relevant anatomical structures are described here only with regard to their relevant innervation and potential for generating pain. The periosteum that lines the outer surface of each vertebrae is richly innervated; there is also a high concentration of large intraosseous nerves within the bone marrow and in the central region of the cartilaginous end plate adjacent to the nucleus of the intervertebral disk (1,2). The primary function of the cervical intervertebral disk is largely biomechanical—to absorb shock, distribute load, and transmit compressive loads through the spinal column. However, its anatomy also suggests that it may have the capacity for sensation; the outer third of the annulus fibrosus of the normal disk is innervated by free nerve terminals, which are the unencapsulated endings of afferents that typically respond to noxious stimuli (2, 3 and 4). These free nerve endings in the disk can be stimulated by disk degeneration, direct mechanical loading, and/or exposure to chemical mediators (5,6). Despite these anatomic suggestions supporting the hypothesis that the disk has the potential to generate pain, no studies have documented molecular or cellular modifications relevant to persistent neck pain arising from the disk. Certainly, the effects of aging and degeneration on the disk and all of the components of the cervical spine present a major pathway for initiating pain and inducing changes similar to those reported in low back pain (7,8).

The cervical vertebrae are connected by many ligaments in the ventral and dorsal regions of the spine that stabilize the head and neck and provide feedback on joint position during normal motion (Fig. 8.1). The ligaments

of the cervical spine are abundantly innervated and include small diameter nerves with free nerve endings that respond to noxious stimuli (9,10). Immunohistochemical studies have identified nerve fibers that are immunoreactive to the neuropeptides substance P and calcitonin generelated peptide (CGRP) that are expressed primarily by nociceptors (11, 12, 13 and 14). The presence of nociceptors in spinal ligaments also indicates that injury or excessive strain of those tissues (as can occur during abnormal motions of the head/neck) may activate their pain afferents.

of the cervical spine are abundantly innervated and include small diameter nerves with free nerve endings that respond to noxious stimuli (9,10). Immunohistochemical studies have identified nerve fibers that are immunoreactive to the neuropeptides substance P and calcitonin generelated peptide (CGRP) that are expressed primarily by nociceptors (11, 12, 13 and 14). The presence of nociceptors in spinal ligaments also indicates that injury or excessive strain of those tissues (as can occur during abnormal motions of the head/neck) may activate their pain afferents.

The cervical articular facet joint is a complex articulation with a variety of anatomical sources in the joint that can generate pain (Fig. 8.1). The surfaces of the bony articular facets are covered with articular cartilage and the space between the facet surfaces contains synovial folds that absorb shock, distribute pressure, and maintain stability for articulation. The facet capsular ligament, or facet capsule, is a thin ligament that loosely encloses the entire joint. Overall, the cervical facet joints are innervated by the medial branches of the dorsal primary ramus from the two levels superior and inferior to the joint (15). Histologic and anatomic studies have identified mechanoreceptors and unmyelinated nociceptors in the cervical facetjoint and its capsule (16, 17 and 18). Although the size of the receptive fields of these pain fibers remains unknown, it has been speculated that each fiber may innervate an area large enough to collectively cover the entire joint (19). Regardless, anatomical evidence of pain-producing elements in the facet joint of the cervical spine is convincing and suggests that the joint as a whole, and its individual components, have the potential to induce pain. Coupling the neuroanatomy of this joint with the compressive loading of its synovial folds and the tensile loading of its capsule, it is a very likely candidate for the generation of neck pain, particularly given the complicated nature of its biomechanics during many scenarios of neck loading. In addition, clinical studies have demonstrated pain provocation with distention of the facetjoint from injections of contrast medium (20, 21 and 22) and pain relief when the nerves that innervate facet joints are directly ablated using percutaneous radiofrequency (23, 24 and 25). Together, the complex anatomy, the potential varied biomechanical environments of the cervical facet joints, and the clinical evidence strongly suggest this joint’s involvement as a source of neck pain.

It is important to recognize that neck musculature plays a unique role in neck pain—by the potential for its own injury and via altering the kinematics and kinetics of other structures of the cervical spine that potentially lead to exacerbation of existing loading and painful conditions. Muscles contain nerve fibers, both Aδ – and C-type fibers, which have unencapsulated free nerve endings (19,26). In fact, as many as half of the neural units in skeletal muscle have been identified as having a nociceptive function (27). In many neck loading scenarios, the muscles themselves may simultaneously undergo eccentric contraction while also being elongated as a result of head or torso motions (28). This concomitant lengthening and force exertion makes cervical muscles particularly susceptible to overstretching and possible disruption to the normal function of individual muscle fibers (28,29).

Breakdown products of these sorts of injuries can lead to local inflammatory responses in the injured muscle that also lead to a more severe pain response when the muscle undergoes further injurious loading (29, 30 and 31). The sensitization of muscle nociceptors through inflammation is also a common peripheral mechanism for tenderness and pain in damaged muscle (32). Not only are neck muscles at risk for their own injury, but they also pose a threat to the other spinal tissues in which they insert or make direct contact. For example, fibers from the semispinalis and splenius capitis muscles insert directly on the facet capsule in the cervical spine (33), presenting a direct pathway for added loading to the capsule when these muscle fibers become activated. Such direct mechanical aggravation via muscles can superimpose additional injury on a potentially already injured or painfully stimulated joint, offering a mechanism for inducing a more severe pain state.

Breakdown products of these sorts of injuries can lead to local inflammatory responses in the injured muscle that also lead to a more severe pain response when the muscle undergoes further injurious loading (29, 30 and 31). The sensitization of muscle nociceptors through inflammation is also a common peripheral mechanism for tenderness and pain in damaged muscle (32). Not only are neck muscles at risk for their own injury, but they also pose a threat to the other spinal tissues in which they insert or make direct contact. For example, fibers from the semispinalis and splenius capitis muscles insert directly on the facet capsule in the cervical spine (33), presenting a direct pathway for added loading to the capsule when these muscle fibers become activated. Such direct mechanical aggravation via muscles can superimpose additional injury on a potentially already injured or painfully stimulated joint, offering a mechanism for inducing a more severe pain state.

NEURAL COMPONENTS

The spinal cord is surrounded by three membranes, comprising the meninges: the pia mater, arachnoid, and dura mater. The pia matter is in closest contact with the cord and the dura mater encloses the entire structure. Cerebrospinal fluid is contained between the arachnoid and the pia, and the epidural space exists between the dura and the inside of the bony walls comprising the spinal canal. The dura mater contains small nerve fibers that express CGRP and substance P (14,34,35). However, compared to the cranial meninges, the spinal dura mater may play a limited role in the pathogenesis of pain (34). Despite this, the spinal meninges may have a role in the modulation of pain because of their ability to release proinflammatory cytokines into the cerebrospinal fluid (36).

Anterior and posterior rootlets come off the spinal cord and combine to form the dorsal and ventral nerve roots that make up the bilateral spinal nerves at each level (Fig. 8.1). The location, direction, and number of nerve rootlets vary with each cervical level. The posterior rootlets that make up the dorsal root are the sensory fibers, and the anterior rootlets are the effecter fibers. The anterior and posterior roots come together in the region of the neuroforamen and continue more distally into the periphery as the spinal nerve, to innervate structures outside the spinal column. Unlike nerves, the nerve roots are not enclosed by a thick epineural sheath, and so they lack the mechanical strength of their peripheral counterparts, placing nerve roots in a potentially injurious situation when they are loaded. The cell bodies of peripheral nerves are housed in the dorsal root ganglion (DRG) (Fig. 8.1). The DRG is particularly sensitive to loading; even slight compression of normal DRGs can produce sustained neuronal activity and pain (37, 38 and 39). Certain extreme movements of the cervical spine can change the shape of the neural foraminae and/or decrease the foramen and directly deform the nerve root (40, 41, 42, 43, 44 and 45). Direct neural impingement can occur slowly by stenosis and/or osteophytic growth or by a herniated disk. In addition, transient loading of the cervical nerve roots can also produce pain in sports-related injuries (such as “stingers” and “burners”), as well as behavioral sensitivity and nociceptive cascades in several animal models that will be discussed in a later section.

VASCULAR COMPONENTS

The vascular components of the neck are themselves not viable sources of pain. However, the vertebral arteries can be injured directly or indirectly through interactions with the surrounding hard and soft tissues. Vertebral artery damage can have serious consequences including compromised blood supply to the brain and pressure gradients around the spinal cord that may lead to nociceptive responses and/or pain (46, 47, 48 and 49). The vertebral arteries arise from the subclavian arteries and ascend through the transverse foraminae from the sixth to the first cervical vertebrae, to supply blood to the head, brain, and neck tissues. These vessels can undergo shape changes and deformations during both normal and abnormal neck movements because they pass through rigid bony channels and are linked by connective tissue to these channels at each vertebral level (50, 51, 52 and 53). Furthermore, the vertebral artery can undergo sudden changes in direction in the atlantoaxial region of the upper cervical spine where it is required to pass over bony landmarks in this very mobile region of the cervical spine, making it particularly vulnerable to damage from adverse mechanical events in the neck (48,50,54). Interestingly, the blood supply from the vertebral artery has been shown to be interrupted during a variety of benign activities such as shoulder checking, sleeping awkwardly, riding roller coasters, or motor vehicle accidents (55, 56, 57 and 58). These injuries and their physiologic consequences cause headache and neck pain, vertigo, unilateral facial paresthesia, or visual field defects (47).

Each of the anatomical structures of the cervical spine described above is important in a variety of neck injuries and pathologies leading to neck pain syndromes. The majority of neck pain comes from a complicated constellation of biomechanical contributions, including multiaxial and combined loading, rate effects of tissue loading, and the duration of loading. So, it is more often the case that several anatomical structures undergo complex loading profiles simultaneously. Studying the injury and pain-generating potential of each anatomical structure individually gives insight into the mechanisms by which persistent pain develops; accordingly, pain originating from each of these potential sources are discussed separately, later in this chapter.

MECHANISMS OF PAIN

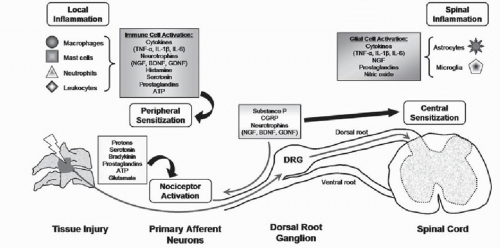

Broadly, an inciting event and fiber stimulation initiate local responses and can lead to a host of central signaling events that include neuronal and immune responses (Fig. 8.2). In persistent pain, CNS modifications lead to hypersensitivity and central sensitization, which is described as a heightened response to stimuli mediated by signal amplification in the spinal cord (59). In addition to neuronal sensitization, the CNS also mounts a widespread and sustained neuroimmune response that further contributes to neuronal plasticity and persistent pain. Here we briefly highlight both of these collections of responses for

acute injury and nociceptive pain, as well as for persistent pain.

acute injury and nociceptive pain, as well as for persistent pain.

TISSUE INJURY AND NOCICEPTIVE PAIN

Physiologic pain, or “nociceptive pain,” is produced by noxious stimuli that activate small-diameter unmyelinated C-fibers or medium-diameter thinly myelinated Aδ sensory neurons (26). Collectively, both types of nociceptors transmit signals from the periphery to the CNS via their afferents that have cell bodies in the DRG and terminate in the dorsal horn of the spinal cord (Fig. 8.2), where they communicate with spinal neurons via synaptic transmission (59,60). Many neurotransmitters (e.g., substance P, CGRP, glutamate, ATP, and others) communicate the signals from the peripheral afferents to spinal cord neurons (Fig. 8.2). Histochemical studies have identified two major classes of nociceptors that synapse in different regions of the superficial dorsal horn of the spinal cord (61, 62 and 63). Peptidergic nociceptors express the neurotransmitters substance P and CGRP and terminate almost exclusively in the most superficial laminae of the dorsal horn (62,63). Nonpeptidergic neurons, selectively labeled by isolectin B4, express the purinergic receptor, P2X3, that mediates nociceptor excitation by ATP and synapses with second-order interneurons in lamina II of the dorsal horn (62,63). These nociceptor populations also express receptors for different growth factors; most peptidergic neurons express the tyrosine kinase receptor A, suggesting that they depend on nerve growth factor (NGF) for survival, and the nonpeptidergic neurons express one of the glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor (GDNF) family receptors (GFRα1-4) (64). The distinct neurochemistry of these two classes of nociceptors has come to suggest that they are involved in different pain transmission circuits in the spinal and supraspinal sites of the CNS (62,63). More detailed specific signaling responses of the spinal cord are complex, numerous, and detailed elsewhere in the literature (60,65).

Nociceptive pain provides protection against tissue injury and continues only in the presence of sustained noxious stimuli (59). Following a tissue injury, local nociceptors may become sensitized and can exhibit both lower thresholds for firing and increased firing rates when exposed to previously nonnoxious stimuli (59,62,66). This peripheral sensitization is due largely to the production and peripheral release of neurotransmitters and/or other factors from neurons and other nonneuronal cells (e.g., mast cells, neutrophils, platelets, fibroblasts) that can infiltrate the injured area (Fig. 8.2) (62,67). Multiple mediators, including bradykinin, amines, prostanoids, NGF, and protons, all act rapidly via receptors on the nociceptor terminals to sensitize these neurons (67). The nociceptive pain response described above encompasses the typical cascade of an acutely painful episode, where the balance of injury, repair, and healing is achieved and the collection of

electrophysiologic and chemical events resolves following inflammation and/or injury. However, for persistent pain, the local, spinal, and supraspinal responses become pathologically and permanently altered from the nociceptive response described above (62). The contribution of the local and widespread inflammatory response plays a large role in the transition to persistent pain and is described in greater detail later in this section.

electrophysiologic and chemical events resolves following inflammation and/or injury. However, for persistent pain, the local, spinal, and supraspinal responses become pathologically and permanently altered from the nociceptive response described above (62). The contribution of the local and widespread inflammatory response plays a large role in the transition to persistent pain and is described in greater detail later in this section.

NEURONAL MECHANISMS OF PERSISTENT PAIN

Persistent pain is due in large part to spinal sensitization. Although the exact mechanism by which the spinal cord becomes sensitized or in a “hyperexcitable” state remains somewhat unknown, many hypotheses continue to emerge. This section provides only a highlight of these such theories; more extensive discussions can be found elsewhere in the literature (59,67,68). Simply, low-threshold Aβ afferents, which normally do not transmit nociceptive signals, are recruited to transmit spontaneous and movement-induced pain (68). This central hyperexcitability is characterized by a “windup” response of repetitive C-fiber stimulation, expanding receptive field areas, and spinal neurons taking on properties of wide dynamic range neurons (69,70). Ultimately, Aβ-fibers stimulate the postsynaptic neurons, whereas these Aβ-fibers previously responded only to innocuous stimuli. All of these responses lead to central sensitization (68). However, this is by no means the only mechanism by which there is plasticity in the CNS, modifying the nociceptive pathways.

Stimulation of, or damage to, peripheral afferents induces the production and release of several trophic factors, in addition to neurotransmitters. Many neurotrophins, and NGF in particular, act as important mediators and modulators of pain (64,65,71). NGF is upregulated in many chronic pain conditions, and it can also modulate pain through a second neurotrophin, brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) (71,72). BDNF is released from the spinal terminals of peptidergic nociceptors where it acts through its receptor, tyrosine kinase B, and leads to central sensitization by potentiating glutamate neurotransmission in the dorsal horn and promoting the synaptic rearrangement of the Aβ-fibers discussed above (71,73,74). Although NGF and BDNF exclusively modulate peptidergic pathways (64), GDNF is expressed in nonpeptidergic neurons and also acts as a spinal neuromodulator (75,76). NGF’s pronociceptive effect has been demonstrated by the administration of anti-NGF treatment to effectively alleviate abnormal pain sensitivity in experimental models of inflammatory and neuropathic pain (71,77,78). However, both BDNF and GDNF can also be antinociceptive when delivered in high concentrations directly to the spinal cord and/or midbrain (76,79). While it has been well accepted that neurotrophic factors are necessary for the long-term survival of neurons, emerging evidence makes a strong case for their involvement as crucial mediators of persistent pain. Neurotrophins also appear to have indirect actions on nociceptors, since they are synthesized and released by several types of immune cells, including mast cells and lymphocytes (74).

NEUROIMMUNOLOGIC RESPONSES IN THE CNS

Although the neuronal responses in the peripheral and CNSs contribute to persistent pain, recent research has demonstrated the role of neuroimmune responses in the CNS as contributing to persistent pain (Fig. 8.2) (74,80, 81, 82 and 83). Here we briefly highlight neuroimmune activation and neuroinflammatory responses in the context of other nociceptive cascades to provide a foundation for understanding these responses in pain.

Tissue damage results in the release of many chemical mediators (e.g., bradykinin, serotonin, protons) that initiate a neuroimmune cascade in which many nonneuronal cells in the periphery are activated (Fig. 8.2) (62,74,80). These resident cells, including mast and Schwann cells, release mediators such as histamine, prostaglandins, cytokines, and chemokines that also lead to the recruitment of other infiltrating immune cells (e.g., neutrophils, macrophages, lymphocytes) (Fig. 8.2). Cytokines, including the interleukins (i.e., IL-1β, IL-6) and tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α), may indirectly or directly affect nociception. It is generally accepted that the cytokine cascade is responsible for the infiltration of immune cells to the site of injury (66,74,80). Proinflammatory cytokines also trigger the release of many other inflammatory mediators that are responsible for nociceptor sensitization, further maintaining neuronal excitability and sensitization, and leading to pain (66,74) (Fig. 8.2). However, TNF-α and IL-1β can also directly sensitize nociceptors during inflammation since sensory neurons have been reported to express receptors for these cytokines (66,84).

Activation of peripheral nociceptors in response to the peripheral neuroimmune and neuroinflammatory activities also activates glial cells in the CNS. Microglia are the resident macrophages in the CNS. Astrocytes have many roles in the CNS, including the maintenance of homeostasis at neuronal synapses. Both types of glial cells respond to injury by changing their morphology, proliferating, upregulating cell-surface markers, and releasing several inflammatory mediators (83,85, 86 and 87). Spinal microglial are activated early after peripheral injury by some neurotransmitters/neuromodulators (e.g., excitatory amino acids, substance P, ATP) (87,88), and when activated they release several proinflammatory cytokines (IL-1β, TNF-α, IL-6), as well as nitric oxide, prostaglandins, and NGF (82,85). These mediators, in turn, induce the exaggerated release of neurotransmitters from presynaptic neurons, sensitize the postsynaptic membrane, activate neighboring astrocytes, and enhance microglial activity (82,85). This positive feedback sustains the release of pain mediators, facilitating the development of neuronal hypersensitivity and leading to persistent pain.

PAIN FROM SPECIFIC TISSUES IN THE NECK

With a mechanistic picture of the generalized cellular responses for pain (Fig. 8.2), we turn our attention to the mechanisms by which various structures in the neck may generate pain. While the exact injury mechanisms leading

to neck pain remain largely uncharacterized, several hypotheses indicate a consensus agreement on the potential sites of injury as well as how pain can originate from these sites. Until recently, there has been limited research related specifically to neck pain; as such, much of the insight for neck pain has come by extrapolating findings from the lumbar spine. However, recent work has focused on the cervical spine, particularly to understand mechanisms of acute and chronic whiplash injury, pain from disk herniation, and neural trauma. This work will be discussed with regard to the biomechanics of injury and the constellation of nociceptive mechanisms related to pain generation and maintenance.

to neck pain remain largely uncharacterized, several hypotheses indicate a consensus agreement on the potential sites of injury as well as how pain can originate from these sites. Until recently, there has been limited research related specifically to neck pain; as such, much of the insight for neck pain has come by extrapolating findings from the lumbar spine. However, recent work has focused on the cervical spine, particularly to understand mechanisms of acute and chronic whiplash injury, pain from disk herniation, and neural trauma. This work will be discussed with regard to the biomechanics of injury and the constellation of nociceptive mechanisms related to pain generation and maintenance.

In vivo models of injury have provided the major platform to define relationships between the activation of the nociceptive system and pain symptoms. In this context, a variety of behavioral assessments has served as the primary functional outcomes for pain measures. Such behavioral metrics are defined in the context of the applied stimulus and the response relationship (www.iasp-pain.org) and are directly related to the clinical presentation of symptoms. Hyperalgesia is an increased response to a stimulus that is normally painful, suggesting that more pain is perceived when suprathreshold stimulation is provided. On the other hand, allodynia is pain evoked by a stimulus that is usually not painful and reflects a loss of specificity of a sensory modality. Both of these behavioral responses are gauges of hypersensitivity and serve as quantitative outcomes of pain symptoms (89).

FACET JOINT INJURY MECHANISMS

The facet joint has been identified as the most common source of neck pain (90,91), accounting for as many as 62% of neck pain cases. Blocks to the nerves of this joint and provocative testing have both implicated the facet joint in neck pain and particularly for whiplash patients (15,25,92). In addition, stretch of the capsule can occur during spinal motions that load the facet joint (Fig. 8.1), suggesting its potential for painful loading during some spinal motions (93, 94, 95, 96 and 97). More recent work has implemented techniques in vivo to define relationships between facet capsule loading, nociceptor activation, and behavioral assessments (26,98, 99, 100, 101, 102, 103 and 104). With these studies, there is mounting evidence to support some forms of loading to the facet capsule as being possibly injurious or painful.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree