4

PARKINSON’S DISEASE

OVERVIEW OF PARKINSON’S DISEASE

James Parkinson wrote and published “An Essay on the Shaking Palsy” in 1817.1 However, in India, paralysis agitans was described under the name Kampavata in the Ayurevedic literature as far back as 4500 bc. Mucuna pruriens (a tropical legume), which they called Atmagupta, was used to treat Kampavata. The seeds of Mucuna pruriens are a natural source of therapeutic quantities of levodopa.2

Parkinson’s disease (PD) is a neurodegenerative disease characterized by slowly progressive symptoms of resting tremor, rigidity, akinesia/bradykinesia, and postural instability.

Parkinson’s disease (PD) is a neurodegenerative disease characterized by slowly progressive symptoms of resting tremor, rigidity, akinesia/bradykinesia, and postural instability.

PD is the second most common neurodegenerative disease after Alzheimer disease.

PD is the second most common neurodegenerative disease after Alzheimer disease.

PD affects about 2% of the population over 60 years.

PD affects about 2% of the population over 60 years.

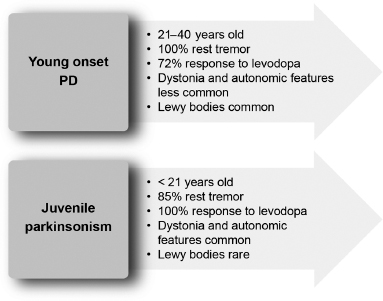

Incidence rates of PD are 8 to 18 per 100,000 person-years.3 In 3% to 5% of patients with parkinsonism, the onset is before the age of 40 years.4 Figure 4.1 compares young-onset PD with juvenile parkinsonism.5,6

Incidence rates of PD are 8 to 18 per 100,000 person-years.3 In 3% to 5% of patients with parkinsonism, the onset is before the age of 40 years.4 Figure 4.1 compares young-onset PD with juvenile parkinsonism.5,6

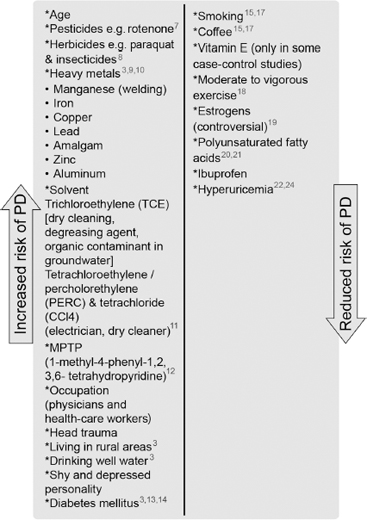

Age is the single most consistent risk factor. Figure 4.2 outlines factors that have been reported to increase and decrease the risk for developing PD.3,7–24

Age is the single most consistent risk factor. Figure 4.2 outlines factors that have been reported to increase and decrease the risk for developing PD.3,7–24

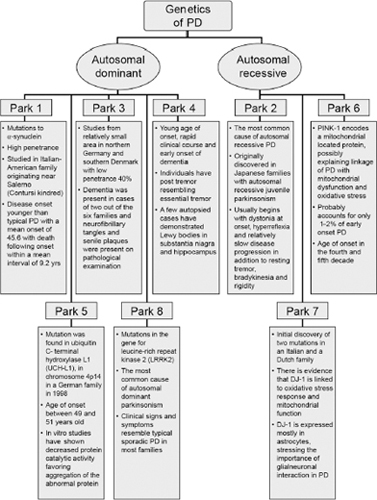

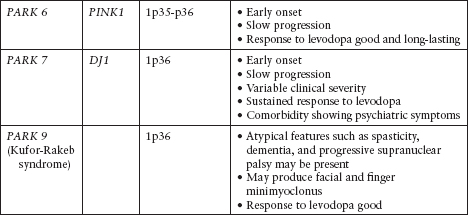

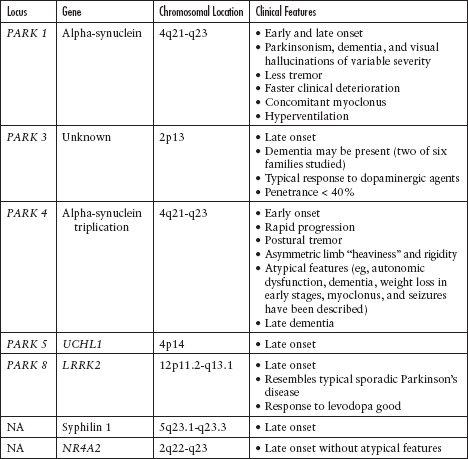

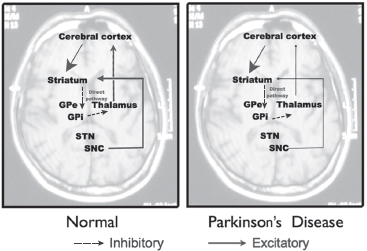

Although the majority of cases of PD are sporadic, there are known and increasingly reported genetic and familiar forms of PD (Figure 4.3; Tables 4.1 and 4.2).25–35

Although the majority of cases of PD are sporadic, there are known and increasingly reported genetic and familiar forms of PD (Figure 4.3; Tables 4.1 and 4.2).25–35

Most inherited forms of PD present at a younger age.

Most inherited forms of PD present at a younger age.

Figure 4.1

Differences between young-onset Parkinson’s disease and juvenile-onset parkinsonism.

From Refs. 5, 6.

Mitochondrial Inheritance

So far, data fail to demonstrate a bias toward maternal inheritance in familial PD.36

So far, data fail to demonstrate a bias toward maternal inheritance in familial PD.36

There is no association of common haplogroup-defining mitochondrial DNA variants or of the 10398G variant with the risk for PD.

There is no association of common haplogroup-defining mitochondrial DNA variants or of the 10398G variant with the risk for PD.

However, it still remains possible that other inherited mitochondrial DNA variants, or somatic mitochondrial DNA mutations, contribute to the risk for familial PD.

However, it still remains possible that other inherited mitochondrial DNA variants, or somatic mitochondrial DNA mutations, contribute to the risk for familial PD.

PATHOLOGY

The traditional view is that the main pathologic process in PD is the degeneration of dopaminergic neurons in the substantia nigra.

The traditional view is that the main pathologic process in PD is the degeneration of dopaminergic neurons in the substantia nigra.

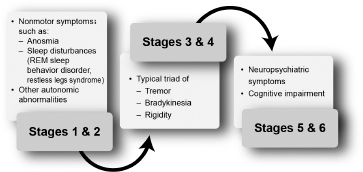

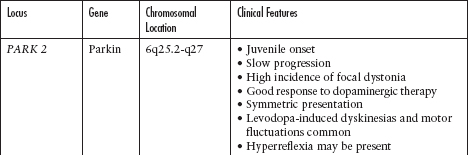

Braak and colleagues have challenged this idea and introduced a six-stage pathologic process (Figure 4.4).37

Braak and colleagues have challenged this idea and introduced a six-stage pathologic process (Figure 4.4).37

In this staging system, degeneration of dopaminergic neurons in the substantia nigra occurs in stage 3 (see Figure 4.4; Figure 4.5).

In this staging system, degeneration of dopaminergic neurons in the substantia nigra occurs in stage 3 (see Figure 4.4; Figure 4.5).

Figure 4.2

Known environmental risk and protective factors for Parkinson’s disease genetics and familial forms of Parkinson’s disease.

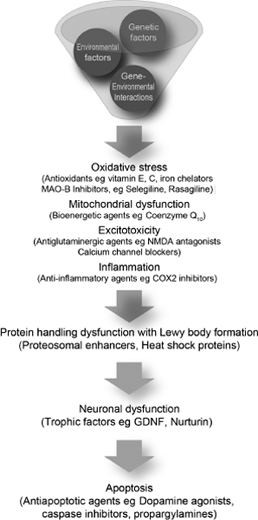

The mechanism responsible for neuronal degeneration is probably multifactorial and based on a combination of genetic and environmental factors (Figure 4.6).38

The mechanism responsible for neuronal degeneration is probably multifactorial and based on a combination of genetic and environmental factors (Figure 4.6).38

Figure 4.3

Summary of autosomal dominant and autosomal recessive Parkinson’s disease.

From Refs. 25–35.

Table 4.1

Autosomal Dominant Parkinson’s Disease

Table 4.2

Autosomal Recessive Parkinson’s Disease

Figure 4.4

Stages of Parkinson’s disease–related pathology according to Braak and colleagues.

From Ref. 37: Braak H, Tredici KD, Riib U, et al. Staging of brain pathology related to sporadic Parkinson’s disease. Neurobiol Aging. 2003; 24:197–211.

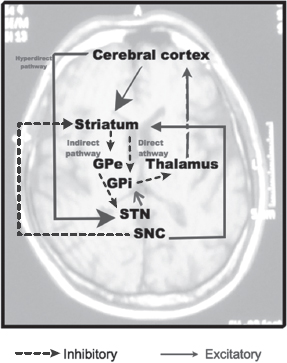

There are three basal ganglia pathways:

There are three basal ganglia pathways:

Direct pathway (cortex—striatum—GPi—thalamus—cortex)

Direct pathway (cortex—striatum—GPi—thalamus—cortex)

Figure 4.5

Clinical features prevalent within the stages of Parkinson’s disease described by Braak and colleagues.

From Ref. 37: Braak H, Tredici KD, Riib U, et al. Staging of brain pathology related to sporadic Parkinson’s disease. Neurobiol Aging. 2003; 24:197–211.

D1 receptors

D1 receptors

Cortical glutaminergic input to the striatal cells

Cortical glutaminergic input to the striatal cells

GABAergic neurons projecting to the globus pallidus internus (GPi)

GABAergic neurons projecting to the globus pallidus internus (GPi)

GABAergic neurons of the GPi projecting to the ventral anterior/ventrolateral nuclei of the thalamus

GABAergic neurons of the GPi projecting to the ventral anterior/ventrolateral nuclei of the thalamus

Indirect pathway (cortex—striatum—GPe—STN—GPi—thalamus—cortex)

Indirect pathway (cortex—striatum—GPe—STN—GPi—thalamus—cortex)

D2 receptors

D2 receptors

Cortical glutaminergic input to the striatal cells

Cortical glutaminergic input to the striatal cells

GABAergic neurons projecting to the globus pallidus externus (GPe)

GABAergic neurons projecting to the globus pallidus externus (GPe)

GABAergic neurons of the GPe projecting to the subthalamic nucleus (STN)

GABAergic neurons of the GPe projecting to the subthalamic nucleus (STN)

STN glutaminergic projection to the GPi

STN glutaminergic projection to the GPi

GPi to thalamus to cortex (similar to the direct pathway)

GPi to thalamus to cortex (similar to the direct pathway)

Hyperdirect pathway (cortex—STN)

Hyperdirect pathway (cortex—STN)

Cortex directly to the STN

Cortex directly to the STN

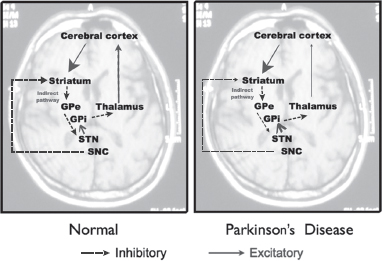

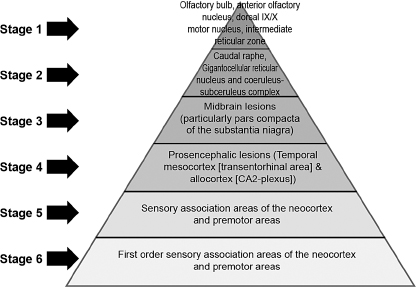

Alteration in the direct pathway leading to PD (Figures 4.7 and 4.8)

Alteration in the direct pathway leading to PD (Figures 4.7 and 4.8)

In normal subjects, dopaminergic neurons in the substantia nigra, pars compacta (SNc) act to excite inhibitory neurons in the direct pathway (see Figure 4.7).

In normal subjects, dopaminergic neurons in the substantia nigra, pars compacta (SNc) act to excite inhibitory neurons in the direct pathway (see Figure 4.7).

From Ref. 38: Schapira AHV, Olanow CW. Neuroprotection in Parkinson disease. JAMA. 2004; 291:358–364.

Figure 4.7

Normal basal ganglia pathway.

Figure 4.8

Direct pathway of the basal ganglia circuit in normal subjects and subjects with Parkinson’s disease.

Figure 4.9

Indirect pathway of the basal ganglia circuit in normal subjects and subjects with Parkinson’s disease.

In PD, dopaminergic cell loss in the SNc results in reduced striatal inhibition of the GPi and substantia nigra, pars reticulata (SNr). The overactivity of the GPi and SNr results in excess inhibition of the thalamus. The final pathway would be a reduced activation of the motor cortex.

In PD, dopaminergic cell loss in the SNc results in reduced striatal inhibition of the GPi and substantia nigra, pars reticulata (SNr). The overactivity of the GPi and SNr results in excess inhibition of the thalamus. The final pathway would be a reduced activation of the motor cortex.

Alteration in the indirect pathway leading to PD (Figure 4.9)

Alteration in the indirect pathway leading to PD (Figure 4.9)

In normal subjects, dopaminergic neurons in the SNc act to inhibit excitatory neurons in the indirect pathway.

In normal subjects, dopaminergic neurons in the SNc act to inhibit excitatory neurons in the indirect pathway.

In PD, there is dopaminergic cell loss in the SNc, resulting in increased striatal inhibition of the GPe. The reduced inhibition of the STN results in increased excitation of the GPi, which in turn results in excess inhibition of the thalamus. The final pathway would be a reduced activation of the motor cortex.

In PD, there is dopaminergic cell loss in the SNc, resulting in increased striatal inhibition of the GPe. The reduced inhibition of the STN results in increased excitation of the GPi, which in turn results in excess inhibition of the thalamus. The final pathway would be a reduced activation of the motor cortex.

NEUROPROTECTION TRIALS

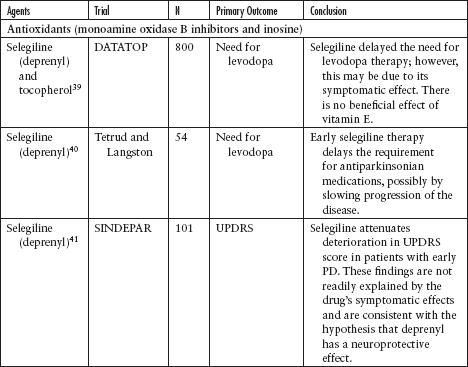

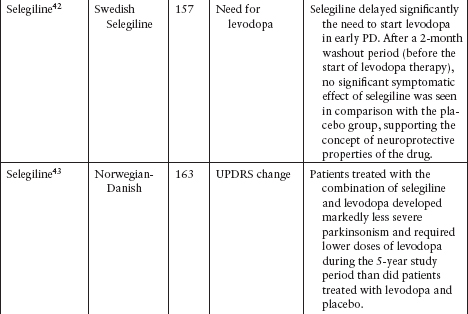

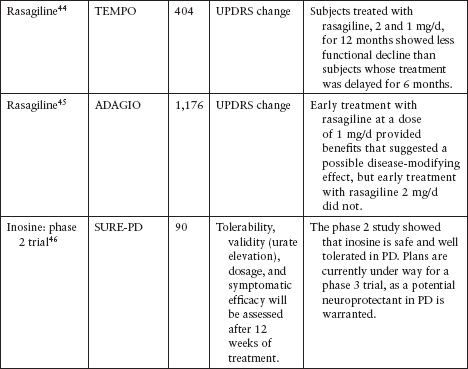

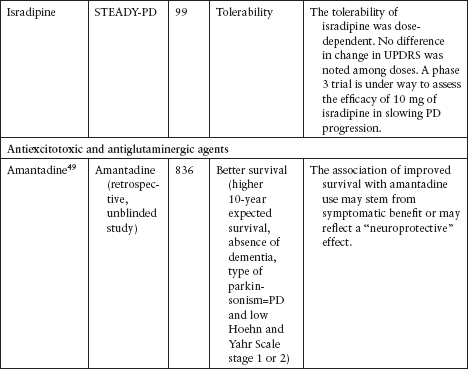

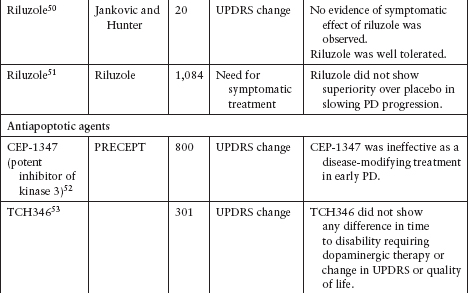

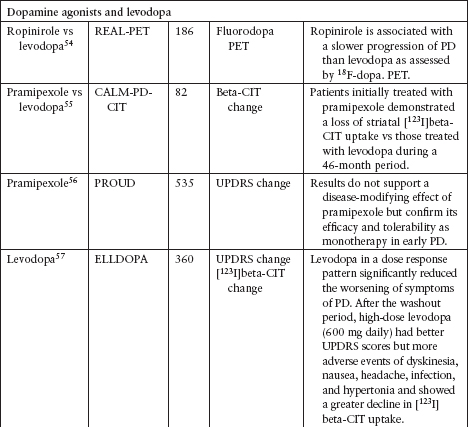

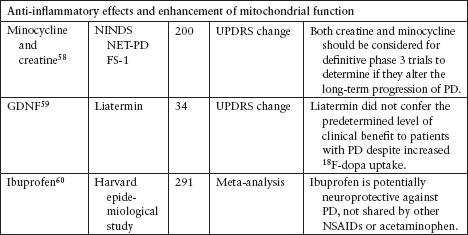

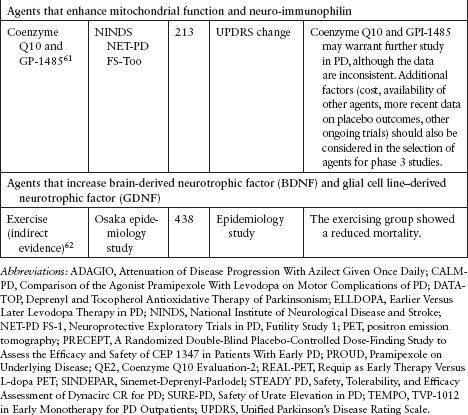

Although several agents have been tested to evaluate their neuroprotective effect in PD, none has been definitively shown to slow disease progression (Table 4.3).39–62

Although several agents have been tested to evaluate their neuroprotective effect in PD, none has been definitively shown to slow disease progression (Table 4.3).39–62

Currently, the clinical data for neuroprotective agents for patients with early PD are conflicting and inconclusive.

Currently, the clinical data for neuroprotective agents for patients with early PD are conflicting and inconclusive.

Clinical endpoints available are readily confounded by agents that also carry symptomatic effects.

Clinical endpoints available are readily confounded by agents that also carry symptomatic effects.

DIAGNOSIS

The diagnosis of PD remains clinical to this day (Figure 4.10). The UK Parkinson’s Disease Society Brain Bank Clinical Diagnostic Criteria have been used as a gold standard diagnostic tool in PD research (Table 4.4).63

The diagnosis of PD remains clinical to this day (Figure 4.10). The UK Parkinson’s Disease Society Brain Bank Clinical Diagnostic Criteria have been used as a gold standard diagnostic tool in PD research (Table 4.4).63

At present, there is no biological marker that unequivocally confirms the diagnosis of PD.

At present, there is no biological marker that unequivocally confirms the diagnosis of PD.

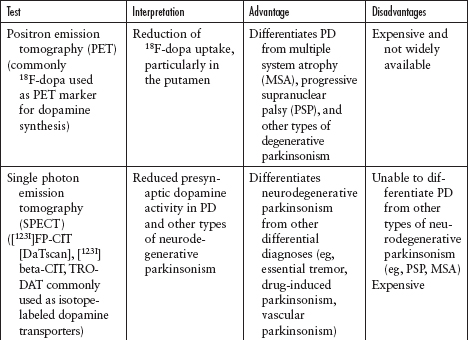

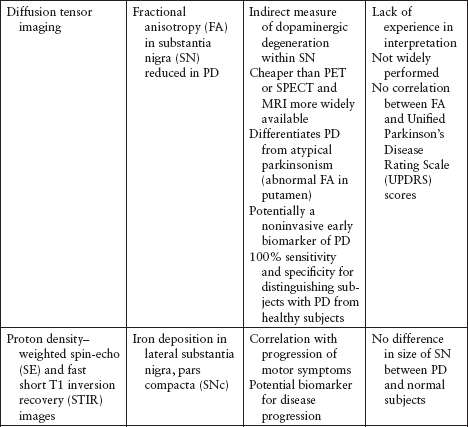

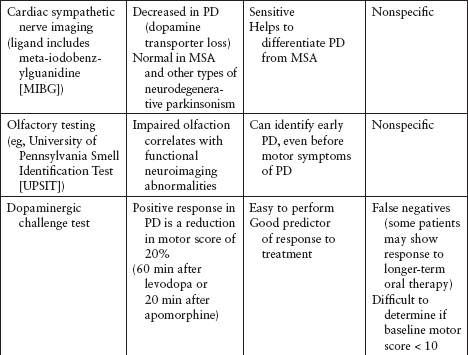

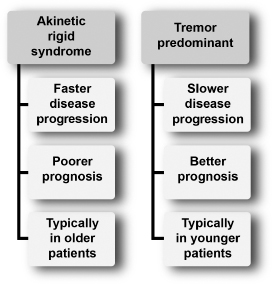

Imaging and other ancillary tests have been utilized (clinically or in PD research) to help confirm the diagnosis of PD (Table 4.5).

Imaging and other ancillary tests have been utilized (clinically or in PD research) to help confirm the diagnosis of PD (Table 4.5).

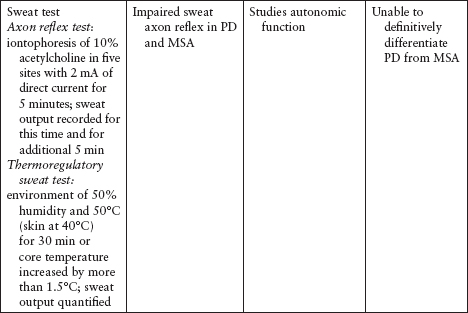

Recently, DaTscan has been approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to differentiate neurodegenerative parkinsonism (eg, PD) from nonneurodegenerative parkinsonism (eg, essential tremor, vascular parkinsonism, drug-induced parkinsonism) (Figure 4.11). However, DaTscan is unable to differentiate PD from other Parkinsonplus syndromes (eg, progressive supranuclear palsy, multiple system atrophy, dementia with Lewy bodies).

Recently, DaTscan has been approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to differentiate neurodegenerative parkinsonism (eg, PD) from nonneurodegenerative parkinsonism (eg, essential tremor, vascular parkinsonism, drug-induced parkinsonism) (Figure 4.11). However, DaTscan is unable to differentiate PD from other Parkinsonplus syndromes (eg, progressive supranuclear palsy, multiple system atrophy, dementia with Lewy bodies).

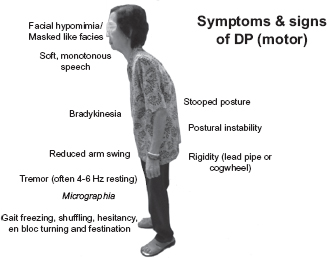

Figure 4.10

Motor features of Parkinson’s disease.

Table 4.4

UKPDS Brain Bank Clinical Criteria

Step 1: Diagnosis • Bradykinesia and at least one of the following: |

Step 2: Exclusion criteria for Parkinson’s disease • History of repeated strokes with stepwide progression of parkinsonian features • History of definite encephalitis • History of repeated head injury • MPTP exposure • Oculogyric crisis • Neuroleptic treatment at onset of symptoms • More than one affected relative • Sustained remission • Strictly unilateral features after 3 years • Supranuclear gaze palsy • Cerebellar signs • Early severe autonomic involvement • Early severe dementia with disturbances of memory, language, and praxis • Babinski sign • Presence of cerebral tumor or communicating hydrocephalus on CT scan • Negative response to large doses of levodopa (if malabsorption excluded) |

Step 3: Supportive criteria for Parkinson’s disease (three or more required for diagnosis of definite Parkinson’s disease) • Unilateral onset • Resting tremor • Progressive disorder • Persistent asymmetry with side of onset affected to greater degree • Excellent response (70%–100%) to levodopa • Severe levodopa-induced chorea • Levodopa response for 5 years or more • Clinical course of 10 years or more |

Abbreviation: UKPDS, UK Parkinson’s Disease Society Brain Bank Clinical Diagnostic Criteria.

Source: Adapted from Ref. 63: Gibb WR, Lees AJ. The relevance of the Lewy body to the pathogenesis of idiopathic Parkinson’s disease. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1988;51:745–752.

Figure 4.11

Single photon emission computed tomographic scan of a patient with Parkinson’s disease showing decreased tracer uptake in the bilateral putamen, suggestive of loss of dopaminergic neuronal terminal density in the striatum.

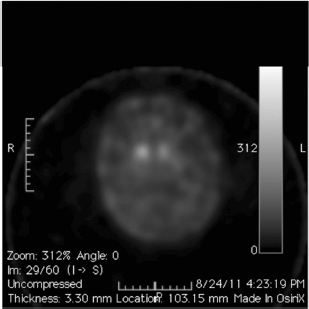

The PD motor presentation can be divided into two phenotypes (Figure 4.12).

The PD motor presentation can be divided into two phenotypes (Figure 4.12).

Akinetic–rigid syndrome or postural instability gait dysfunction subtype (PIGD)

Akinetic–rigid syndrome or postural instability gait dysfunction subtype (PIGD)

Tremor-predominant subtype

Tremor-predominant subtype

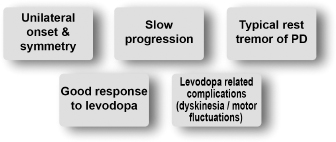

Certain clinical features, such as resting tremor, asymmetry of parkinsonian motor symptoms, and good response to levodopa, strongly suggest PD rather than a Parkinson-plus syndrome (Figure 4.13).

Certain clinical features, such as resting tremor, asymmetry of parkinsonian motor symptoms, and good response to levodopa, strongly suggest PD rather than a Parkinson-plus syndrome (Figure 4.13).

The akinetic–rigid syndrome or PIGD subtype is more challenging to differentiate from other Parkinson-plus syndromes.

The akinetic–rigid syndrome or PIGD subtype is more challenging to differentiate from other Parkinson-plus syndromes.

Clinical Rating Scale for Parkinson’s Disease

There is currently no biomarker to assess the severity of PD.

There is currently no biomarker to assess the severity of PD.

The severity of PD is based mainly on the clinical features.

The severity of PD is based mainly on the clinical features.

Figure 4.12

Clinical phenotype of Parkinson’s disease.

Figure 4.13

Features suggestive of Parkinson’s disease compared with other causes of parkinsonism.

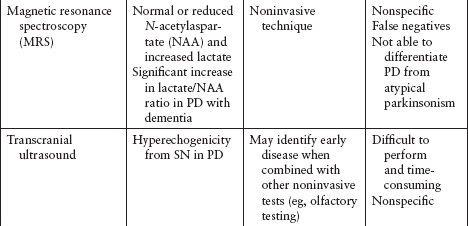

The Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale (UPDRS) is the most widely used scale to assess PD severity and symptomatic motor improvement in treatment trials and in clinical practice (Table 4.6).64–67

The Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale (UPDRS) is the most widely used scale to assess PD severity and symptomatic motor improvement in treatment trials and in clinical practice (Table 4.6).64–67

Nonmotor Symptoms of Parkinson’s Disease

Almost all PD patients will develop nonmotor complications (Table 4.7).

Almost all PD patients will develop nonmotor complications (Table 4.7).

Always ask patients (or their caregivers) about these nonmotor symptoms!

Always ask patients (or their caregivers) about these nonmotor symptoms!

Table 4.6

Comparison of Scales in Parkinson’s Disease

Scale | Advantages | Disadvantages |

Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale (UPDRS)64 | • Most widely used “gold standard” | • Length of scale (about 17 min required for experienced users) • Less emphasis on neuropsychiatric symptoms and other nonmotor symptoms |

Movement Disorder Society–sponsored revision of Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale (MDS-UPDRS)65 | • Comprehensive and better instructions and scoring anchor descriptions • Good emphasis on neuropsychiatric symptoms and other nonmotor symptoms • Validated in several languages; ongoing validation in additional languages | • Length of scale • New and therefore not sufficiently tested in clinical trials |

Short Parkinson’s Evaluation Scale/Scale for Outcomes in Parkinson’s Disease (SPES/SCOPA)66 | • Short and practical • High reproducibility | • Lack of assessment of nonmotor symptoms of PD • Not widely used |

Hoehn and Yahr67 | • Short and easy to administer • Correlates well with disease progression • Correlates well with pathology of PD | • Emphasizes only motor component of PD • Lacking detail and not comprehensive |

Source: Adapted from Refs. 64–67.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree