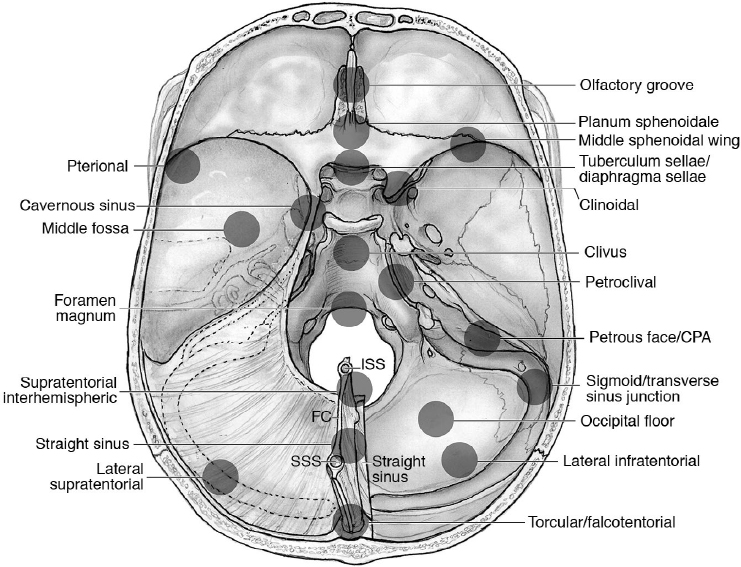

18 Pearls of Skull Base Meningioma Surgery Meningiomas are the among the most frequent skull base tumors, warranting some specific considerations, which are summarized here. • Thirty percent of meningiomas are skull base meningiomas (SBMs).1 Fig. 18.1 shows the localization of skull base meningiomas. • The most frequent SBMs are at the medial sphenoid ridge (~ 30% of SBMs).2 • Eighty percent to 94% of SBMs are grade I, according to the World Health Organization (WHO) grading system.2 WHO grade II and III SBMs are proportionately less common than those in the calvaria (~ 5–10% and 1.3%, respectively),2 suggesting that SBMs may have important differences in tumor biology (e.g., mechanisms of tumorigenesis and progression).3 • Surgical mortality in all meningiomas in the United States is 1.8%.4 Overall, SBMs have lower rates of complete resection than calvarial meningiomas and mortality of about 3 to 5%, with an overall morbidity of about 20 to 40%2 (Table 18.1). • Mortality and morbidity are significantly related to the location and size. Risk groups can be stratified according to the CLASS acronym: comorbidities (C), tumor location (L), patient age (A), tumor size (S), and neurologic signs and symptoms (S)5 (Table 18.2). Risk assessment should take into consideration also the radioanatomic characteristics, such as attachment of the tumor, arterial and cranial nerve involvement, and brainstem relation.6 • Multiple meningiomas occur in fewer than 9% of meningiomas cases but in 50% of patients affected by neurofibromatosis type 2. • Review pathology on page 138. • Skull base meningiomas may grow less often and slower than meningiomas in other locations.7 Table 18.1 Surgical Morbidity in a Single Series of 226 Skull Base Meningiomas2

Epidemiological Pearls

Epidemiological Pearls

Clinical and Surgical Pearls

Clinical and Surgical Pearls

Intracranial hemorrhage | 10.6% |

Cerebrospinal fluid fistula | 8.4% |

Wound infection | 6.6% |

Pulmonary embolism | 4.0% |

Stroke | 1.8% |

Myocardial infarction | 0.9% |

New neurologic deficits | 14.2% (permanent in 3.5%) |

Table 18.2 CLASS Algorithm: Risk Groups Based on the Skull Base Location

Low risk | • Lateral and middle sphenoid wing • Posterior petrous bone |

Moderate risk | • Olfactory groove/planum sphenoidale • Lateral/paramedian tentorium • Cerebellopontine angle • Posterior/lateral foramen magnum |

High risk | • Clinoidal/medial sphenoid ridge • Cavernous sinus • Tuberculum sellae • Medial/incisural tentorium • Clivus |

Source: Adapted from Joung H, Lee BS. The novel “class” algorithmic scale for patient selection in meningioma surgery. In: Lee JH, ed. Meningiomas: Diagnosis, Treatment, and Outcome. Berlin: Springer; 2008 Reprinted with permission.

• Meningiomas are surrounded by multiple arachnoidal layers, and their dissection should be intra-arachnoidal.8 The fine dissection of the double arachnoid plane and “keeping the arachnoid with the patient” enables sparing neurovascular structures. This is my main rule of meningioma surgery.

• Arachnoidal planes are sometimes lost because the tumor origin is outside the arachnoid, and so the tumor growth is not invested with a layer of arachnoid. This enables the tumor to invade the adventitia of arteries or invade cranial nerves (e.g., types I and III clinoidal meningiomas, page 491).

• Attention to the presence or absence of the arachnoid plane and the presence or absence of brain edema on preoperative T2-weighted magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is imperative in all meningioma surgeries.

• Surgical resectability of meningioma can also be related to their consistency. Hypointense tumors on T2-weighted MRI and fluid-attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR) images are generally of harder consistency, whereas those showing hyperintense signals related to higher water content are of softer consistency.9

• Meningiomas calcifications are best diagnosed on computed tomography (CT) scan.

• Large tumors often require internal debulking, which enables decompression of the brain and facilitates identification of the arachnoid plane of dissection. The debulking can be performed with forceps or an ultrasonic aspirator.

• Meningiomas may cause hyperostosis by invasion in the haversian canals,10 and the resection of the involved bone decreases the recurrence rate.11 Skull base involvement is frequent (up to 70%), especially in the middle cranial fossa, and the bone drilling will decrease the risk of recurrence if it is feasible and safe to do so.

The intraoperative use of 5-aminolevulinic acid (5-ALA) has been shown to be a somewhat useful technique (with a specificity of 100% and sensitivity of 89%) for identifying and then removing the bone infiltrated by the meningioma. Fluorescent bone is always infiltrated by the tumor, whereas nonfluorescent bone can contain meningiomatous components in 13% of cases.12

• The goal of meningioma surgery should be total resection in most cases; however, where it is judged to be of excess risk, a subtotal resection can be planned.

• Sixty percent of patients experience recurrence of these tumors after subtotal removal, so these patients must be watched with serial MRI or be offered adjuvant radiation in multiple or single fractions (radiosurgery)13; 28.5% of recurrent meningiomas may transform to a malignant variant.14,15

• The Simpson grading scale of resection, although described in 1957 (pre-microscopic era), is still valuable in predicting recurrence of meningiomas16 (Table 18.3).

• A grade 0 has been added, for the resection of convexity meningiomas, meaning that a 2-cm margin of dura around the tumor is resected.17–19 This is rarely attainable in SBM.

• The Kobayashi scale,21 developed in the microscopic era, although probably more accurate, is rarely used and has not been validated in large studies.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree