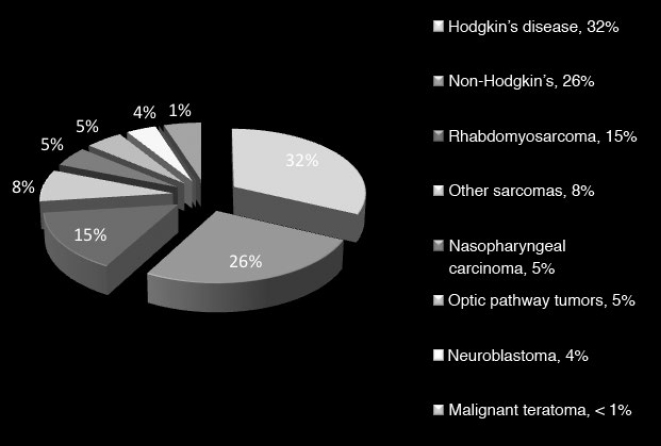

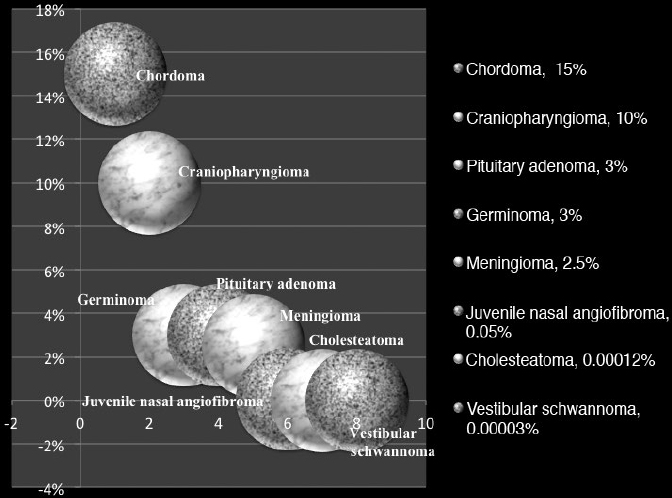

36 Pediatric Skull Base Skull base development is a dynamic process owing its complexity to the progressively changing relative size and orientation of the anterior, middle, and posterior cranial fossae (see Chapter 4). The temporal differences in the fusion of suture lines and the progressive pneumatization of the paranasal sinus and mastoid provide an additional element of complexity in skull base surgery in the pediatric patient. Skull base tumors in children are rare. • Most commonly, they have a mesenchymal origin and the majority of malignant tumors are sarcomas (Fig. 36.1). The anterior and middle cranial fossae are more frequently affected.1 However, overall, malignant intrinsic tumors, such as medulloblastomas, are the predominant tumor, and they have a male predilection (69%).2 • Developmental tumors such as teratomas, choristomas, epidermoids, dermoids, nasal gliomas, and lipomas occur more frequently in children than in adults. In childhood, meningiomas are less common than benign sheath tumors (Fig. 36.2). These tumors are amenable to surgical resection and consequently have a good prognosis.3 Review pathology on page 161. • The estimated incidence of esthesioneuroblastoma is 0.1/100,000 in children up to 15 years of age. It is the most common malignancy of the nasal cavity.4 Fig. 36.2 Pediatric skull base tumors with generally benign clinical behavior (chordomas and juvenile nasal angiofibroma are locally aggressive. Chordomas and malignant meningiomas can metastasize). • Esthesioneuroblastoma has a bimodal age distribution, with one peak in young adult patients and another peak in the 5th to 6th decades. The pediatric age ranges from 11 to 20 years.5 • The differential diagnosis includes lymphoma, sarcoma, anaplastic carcinoma, rhabdomyosarcoma, and transitional cell carcinoma. • Epistaxis (76%), nasal obstruction and difficulty breathing (71%), pain (11%), anosmia, proptosis, and endocrinopathies are the most frequent symptoms.6 • Metastases to cervical lymph nodes, lungs, and bone can be observed in 8 to 30% of cases.7 In patients with metastasis, the 5-year survival is near 0%.3 • The Kadish staging system is widely used to predict outcome and prognosis (see page 653).8 • Surgical resection of low-grade tumors with tumor-free margins is the treatment of choice. • Esthesioneuroblastoma is radiosensitive. Either pre- or postoperative radiotherapy can be used.3 Juvenile nasopharyngeal angiofibroma (JNA) is a benign but locally aggressive and highly vascular tumor. Review the pathology on page 155. • Juvenile nasopharyngeal angiofibroma accounts for 0.05% of head and neck tumors.9 • It occurs in prepubescent boys, starting adjacent to the sphenopalatine foramen. It grows toward adjacent structures, and can invade one nasal cavity and push the nasal septum contralaterally. It can also invade the skull base and intracranial structures, such as the cavernous sinus superiorly and posteriorly, and the maxillary sinus, pterygopalatine fossa, and the orbit laterally. • A hormonal etiology has been proposed because of its prevalence in adolescent boys. • Symptoms include difficulty breathing through the nose (80–90%), epistaxis (45–60%), headache (25%), facial swelling (10–18%), rhinorrhea, anosmia, rhinolalia, and otalgia.10 Some patients present with life-threatening epistaxis. • Since JNA is a highly vascular tumor, marked contrast enhancement is seen on computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). Prominent flow voids, seen on most MRI sequences, give rise to the characteristic “salt-and-pepper” appearance.11 • The differential diagnosis includes rhabdomyosarcoma, nasopharyngeal carcinoma, and nasopharyngeal teratoma. Lymphangioma and encephalocele do not show contrast enhancement. • The treatment of choice is complete surgical removal. A staging classification has been proposed.12 In stage 1 and 2, surgery is the treatment of choice.3 • Preoperative embolization can help to prevent excessive bleeding,12,13 but is only an adjuvant to treatment. Recently, a direct intratumoral embolization has been proposed14 • Radiotherapy has been used as both a primary treatment and as an adjunct to surgery.3 • Because of the rarity of JNA, very few trials of chemotherapy have been reported. The presurgical use of flutamide (a testosterone receptor blocker) for the treatment of JNA has also been reported. In the four cases presented, the average tumor shrinkage was 44% following flutamide use.3 A good preoperative volume reduction with flutamide in postpubertal patients has been reported, but a minimal response is found in prepubertal patients.15 Another series treated five patients for recurrent JNA with doxorubicin, vincristine, dactinomycin, and cyclophosphamide, resulting in tumor remission in all cases.16 Another published report used Adriamycin and dacarbazine in a patient with advanced disease; extensive tumor regression was reported following treatment.17 Chemotherapy, therefore, potentially can be an alternative to radiation in cases of aggressive, unresectable JNA. Rhabdomyosarcoma (RMS) is a rare malignant tumor of striated muscle tissue. It is the most common of the soft tissue sarcomas in children; 35 to 40% of RMSs are located in the head and neck. See pathology on page 166. • Patients with genetic diseases (e.g., Li-Fraumeni syndrome, neurofibromatosis, fetal alcohol syndrome, and nevoid basal cell carcinoma) have an increased risk of developing RMS. In addition, intrauterine exposure to alkylating agents, parental use of marijuana and cocaine, and exposure to X-rays are considered risk factors for RMS.18 • Rhabdomyosarcoma arises from undifferentiated mesenchymal cells, the rhabdomyoblasts. Different histological types are described: embryonal, alveolar, botryoid, and pleomorphic. Embryonal RMS is the most common in the head, neck, and genitourinary tract. In this tumor, the cells are similar to embryo cells of age 6 to 8 weeks. In alveolar RMS, a more aggressive subtype, the cells have a similar appearance to embryo cells of age 10 to 12 weeks. In the botryoid subtype, the cells are similar to embryonal RMS and present as grape lesions. Pleomorphic RMS, most common in adults, is an undifferentiated sarcoma. Alveolar and undifferentiated RMS have a poor prognosis.19 • Presenting symptoms depend on the tumor size and location. Usually RMS presents as an expanding mass. Superficial tumors are detected sooner, but deeply located tumors can be large once they are diagnosed. Typical presentation can include nasal obstruction, pain, and upper respiratory symptoms. Rhabdomyosarcoma often recurs and metastasizes. Metastases involve local lymph nodes in 5% of cases. Lung, liver, bone, and bone marrow are other common sites of RMS metastases. • Rhabdomyosarcoma is classified into stage I through IV based on the amount of tumor spread and the size of residual tumor after surgery.20 • A tumor, node, metastasis (TNM) staging system has been developed and incorporated in the Intergroup Rhabdomyosarcoma Study Group (IRSG)-IV protocol.21 • Treatment of RMS includes surgery, chemotherapy, and radiotherapy. • Whenever possible, surgical removal should be performed with wide (> 1 cm) margins of normal tissue. However, this goal often cannot be achieved in skull base RMS. • Radiotherapy combined with chemotherapy appears to provide the best local control. Several case series have described a survival rate of 60% in patients treated with chemotherapy and radiotherapy. However, the survival rate was only 19% in cases that utilized other treatment regimens.22–25 Older patients, histological alveolar type, and tumor size > 6 cm are risk factors associated with a poor prognosis.22 Fibrous dysplasia is a benign developmental disease. See pages 164 and 533. • Fibrous connective tissue replaces normal lamellar bone. The ribs or craniofacial bones, in particular the maxilla and sphenoid, are often involved. Frequently, fibrous dysplasia may occur in one site as a monostotic form. The polyostotic form, as a part of McCune-Albright syndrome, is rare but has endocrine implications. When more than 50% of the skeleton is involved, fractures and deformities are also common. • Fibrous dysplasia can be asymptomatic or can present with local pain, local swelling or deformity, pathological fracture, cranial nerve involvement with progressive visual or hearing loss, seizures, elevated serum alkaline phosphatase (33%), and spontaneous scalp hemorrhage.26 Fibrous dysplasia can also be associated with Cushing’s syndrome and acromegaly, although this is rare. • Surgery is indicated in cases of neurologic symptoms or progressive deformity. Some authors have advocated early aggressive surgery,27 but complete resection may be difficult and may still be associated with recurrence in up to 25% of patients.28 After adolescence, progression may slow down, so treatment is tailored to specific symptoms. In children, pituitary adenoma (PAs) represent less than 3% of all supratentorial tumors.29 Review pathology on page 143. • In females, prolactinoma causes failure of menarche and galactorrhea; in males, it causes impotence. GH-secreting tumors in children cause gigantism instead of acromegaly, because the epiphyseal plates in the long bones have yet to completely undergo ossification. • ACTH-secreting adenomas cause Cushing’s syndrome, with stunted growth, hypertension, central fat deposition, abdominal purple striae, diabetes or glucose intolerance, and osteoporosis. • Review radiology (Table 5.4, page 118), endocrinology (Chapter 8), and surgical treatment (page 499). • The transsphenoidal endoscopic endonasal approach is the gold standard for PA resection,30,31 but it can be limited in young children due to the small sizes of the nostrils. See endonasal approaches in Chapter 16. Review pathology (page 148) and radiology (Table 5.4, page 119). • Craniopharyngioma accounts for 1.8 to 10% of intracranial tumors in children.3,32 • Clinical symptoms include headache, visual deficits, varying degrees of hypopituitarism, diabetes insipidus, and significant weight gain.33 In cases of hydrocephalus, intracranial hypertension can be the first symptom; it occurs more frequently in children than in adults.32 • Attempts to remove as much of the tumor as possible are preferable for long-term control; however, unfavorable tumor locations (e.g., optic nerve with or without hypothalamic involvement) may be associated with a higher risk of vascular and hypothalamic injury. In these cases, a limited resection followed by radiotherapy may be more prudent. Cyst drainage with insertion of an Ommaya reservoir and judicious use of radiotherapy may lead to long-term control. Intensity-modulated proton therapy in pediatric craniopharyngiomas has been reported to achieve significantly better coverage while minimizing the dosage to normal tissue in comparison to double scattering proton therapy.34 • Extended endoscopic endonasal transsphenoidal approaches and craniotomy are performed with or without orbital cranial osteotomy. Endoscopic endonasal surgery has been shown to have gross total resection high rates in the pediatric population.35 The risks of complications are higher in recurrent cases. • The overall survival rate is 92%, but relapses and reduced quality of life are also frequent.36 Review pathology (page 165) and radiology (page 117). • Chordoma is a slow-growing, locally aggressive tumor that occurs most frequently in the clivus in children and in the sacral region in adults. • Chordoma accounts for 15% of intracranial tumors in children.3 • Metastases occur to lungs, lymph nodes, liver, bone, and adrenals. • A more aggressive behavior in children than in adults has been reported for a prevalent atypical type.37 Malignant transformations into fibrosarcoma or malignant fibrous histiocytoma can also occur, although these transformations are generally quite rare. • Presenting symptoms are cranial nerve (CN) palsies (usually CN III or VI), pain, and obstruction of the sinonasal structures.3 • The best option is radical surgical excision, but gross tumor removal can be difficult to achieve in some cases. • Adjunctive radiotherapy can be used before38 and after surgery.39,40 • Proton beam therapy may achieve better results in children than in adults.41,42 • The treatment of choice can be considered surgery followed by local proton beam therapy. Review pathology (page 138) and radiology (page 114). • Meningiomas are rare and account for 1.5 to 1.8% of intracranial tumors in children.43 • They are associated with neurofibromatosis types 1 and 2 (NF1 and NF2) (see pages 135 and 137). Multiple meningiomas in children are one of the hallmarks of NF2, and their presence should quite clearly suggest this diagnosis.44 • There is a male predilection, with a high incidence of cystic tumors, high-grade meningiomas, and an increased recurrence rate.45 • The treatment of choice is total resection. • When the resection is subtotal, close observation for at least 10 years is recommended. • Patients with NF2 should be considered a special risk, necessitating lifelong follow-up.46 • Papillary meningiomas are malignant subtypes that are more common in pediatric patients. • Malignant subtypes may metastasize outside the central nervous system (CNS) to lungs, liver, lymph nodes, and heart. • Adjuvant radiation therapy is indicated in malignant subtypes, recurrences, or in partial resections. Review pathology (page 135) and radiology (page 117). • In children, vestibular schwannomas are almost always found in cases of NF2, often with bilateral tumors. • Frequent symptoms are progressive hearing loss, disequilibrium, headache, facial weakness, obstructive hydrocephalus, nystagmus, and ataxia. Usually, tumors are already large at the time of diagnosis. • Whenever possible, because of rich vascularization of schwannoma in children, preoperative embolization should be considered.47,48 • Surgical is the treatment of choice in order to preserve hearing, especially in bilateral schwannomas. If needed, the translabyrinthine approach can be used, but it is generally reserved for cases of unilateral deafness. With small tumors, radiosurgery in children has been advocated not only to stop the tumor growth but also to avoid deafness after surgery, especially in cases of bilateral schwannomas.49 • The incidence of congenital cholesteatomas is 0.12 cases per 100,000 people.50 See pathology (page 153) and radiology (page 126). • Cholesteatomas are benign tumors with a congenital or acquired origin. Congenital tumors can be located intracranially or within the skull bones, with almost all bone tumors occurring in the temporal bone. • Intracranial cholesteatomas originate from ectodermal implants trapped in the CNS. In the calvarial location, the ectoderm is trapped in the skull, within the diploe, and expands both the inner and outer tables; secondarily, the calvarial cholesteatoma can involve dural sinuses and intracranial structures.26 • Acquired tumors can originate from epithelium migration after otitis media or tympanic membrane perforation.51 • Symptoms depend on tumor location. These tumors can cause hearing loss or sometimes recurrent episodes of septic meningitis (when a cyst ruptures its contents). • Treatment is typically surgical with the goal of preserving hearing. For temporal bone cholesteatomas, two main strategies have been described: the canal-wall-down mastoidectomy and the canal-wall-up tympanomastoidectomy. The canal-wall-down provides better exposure due to the aggressive removal of the posterior ear canal wall; a common cavity is intentionally formed so that it exists as a bowl after the procedure. This is done with the purpose of improved postoperative surveillance of the disease.52 The canal-wall-up technique is less aggressive in order to preserve hearing, but also carries a high recurrence rate.3 In these techniques, a second look to check for tumor recurrence is needed. When attempting a second look, an endoscopic approach can be less invasive and is more readily accepted by patients.53 • Clinical and radiological long-term follow-up is essential, given the high recurrence rate of 57% after 5 years.54 Ewing’s sarcoma is a primitive neuroectodermal tumor. See pathology on page 166. • Ewing’s sarcoma is the second most common malignant tumor in children. More often located in the spine, Ewing’s sarcoma can involve the skull base in children, sometimes in a massive way. • The presenting symptoms are local pain and swelling. Spectral karyotyping has shown a 11;22 translocation and a frequent Ewing’s sarcoma/FLI1 fusion transcript in cases of Ewing’s sarcoma.55 • Surgery is indicated to decompress neural structures followed by adjuvant chemotherapy, with good reported results. Radiotherapy is used when there is no response to chemotherapy or for localized tumors as an adjunct to surgery.55 See Chapter 37. Craniofacial dysmorphic syndromes are the result of disordered development. Normal development of the face and the skull is interrupted, resulting in a wide group of congenital craniofacial anomalies. Two major categories can be distinguished: those associated with craniosynostoses and those associated with cleft.56 The most common syndromes associated with craniosynostoses are Crouzon, Apert, Pfeiffer, Muenke, and Saethre-Chotzen syndromes. The most common syndromes associated with clefts are Pierre Robin, Treacher Collins, Nager, Binder, and Stickler syndromes. All cases exhibit autosomal dominant inheritance and require a multidisciplinary approach. Timing of surgery has to be planned in consideration of the growing skull. Surgical intervention should be done in stages: craniotomy aims to decompress the brain and is done in infancy; advancement of the middle third improves nasal airflow and may be done in puberty; finally, orthognathic surgery improves occlusion and dental esthetics and may be done in adolescence.57

Tumors in Children

Tumors in Children

Tumors of the Anterior Cranial Fossa

Tumors of the Anterior Cranial Fossa

Esthesioneuroblastoma

Juvenile Nasopharyngeal Angiofibroma

Rhabdomyosarcoma

Fibrous Dysplasia

Tumors of the Central and Middle Skull Base

Tumors of the Central and Middle Skull Base

Pituitary Adenoma

Craniopharyngioma

Tumors of the Posterior Cranial Fossa

Tumors of the Posterior Cranial Fossa

Chordoma

Meningioma

Vestibular Schwannoma

Cholesteatoma or Epidermoid Tumor

Ewing’s Sarcoma

Malformations

Malformations

Encephalocele

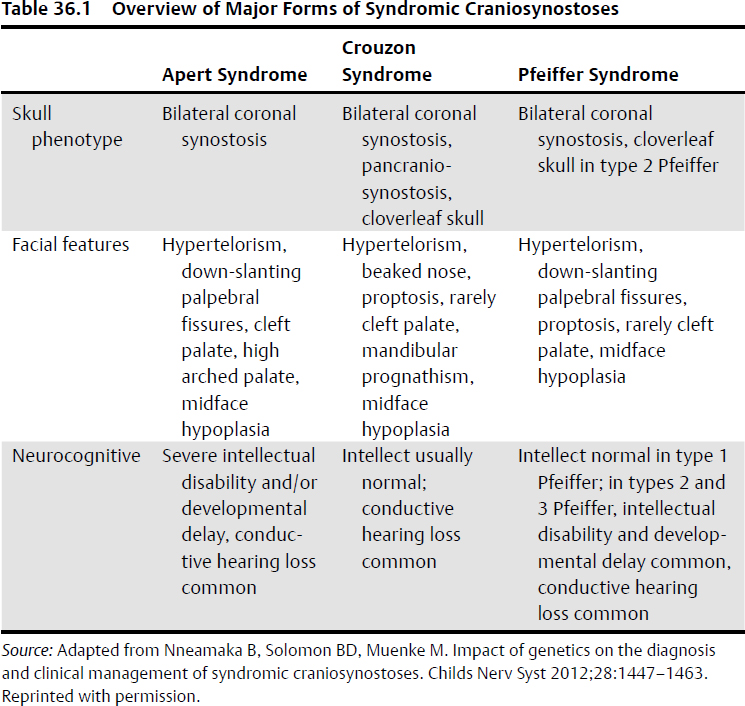

Craniofacial Dysmorphic Syndromes (Table 36.1)

Neupsy Key

Fastest Neupsy Insight Engine