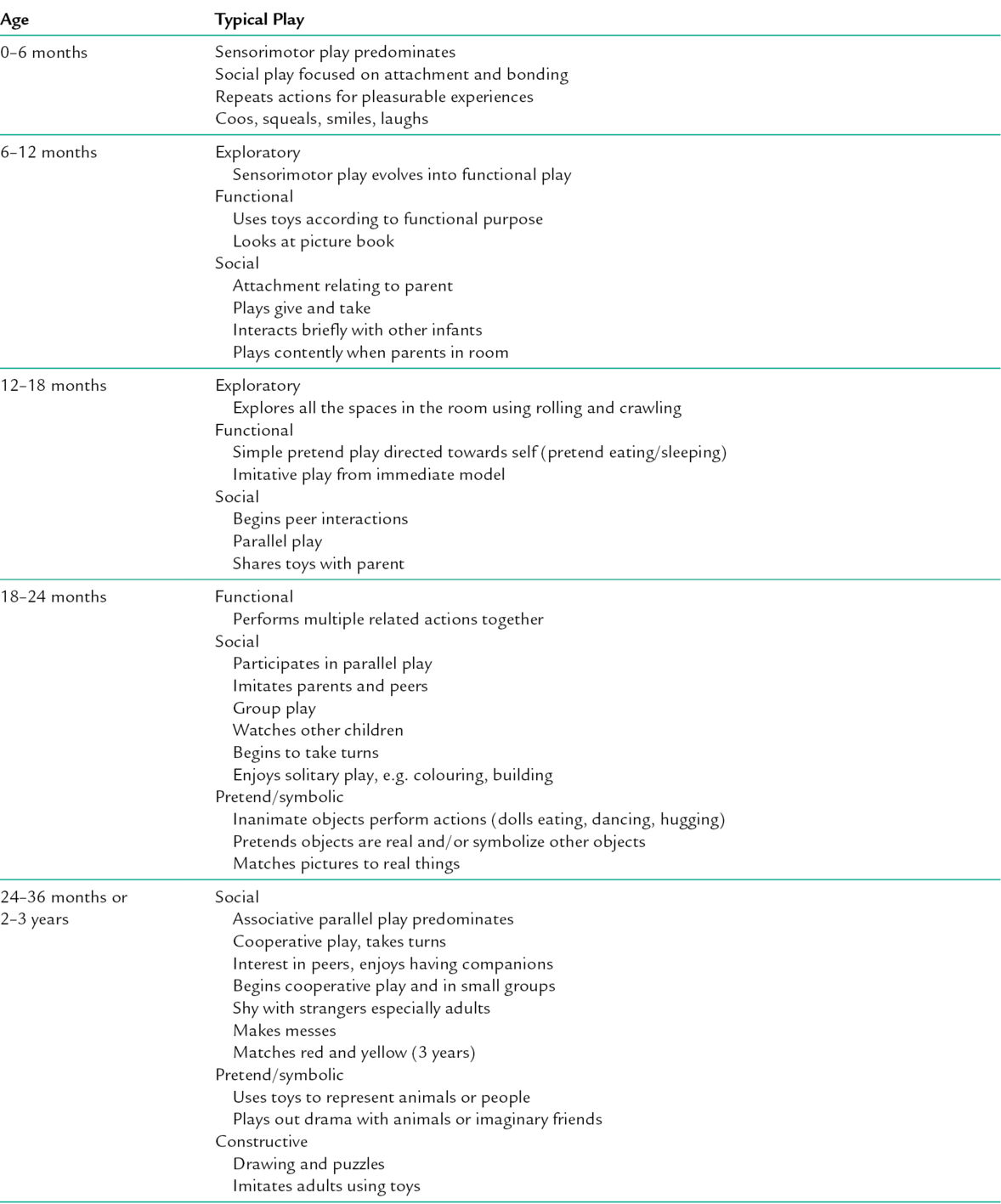

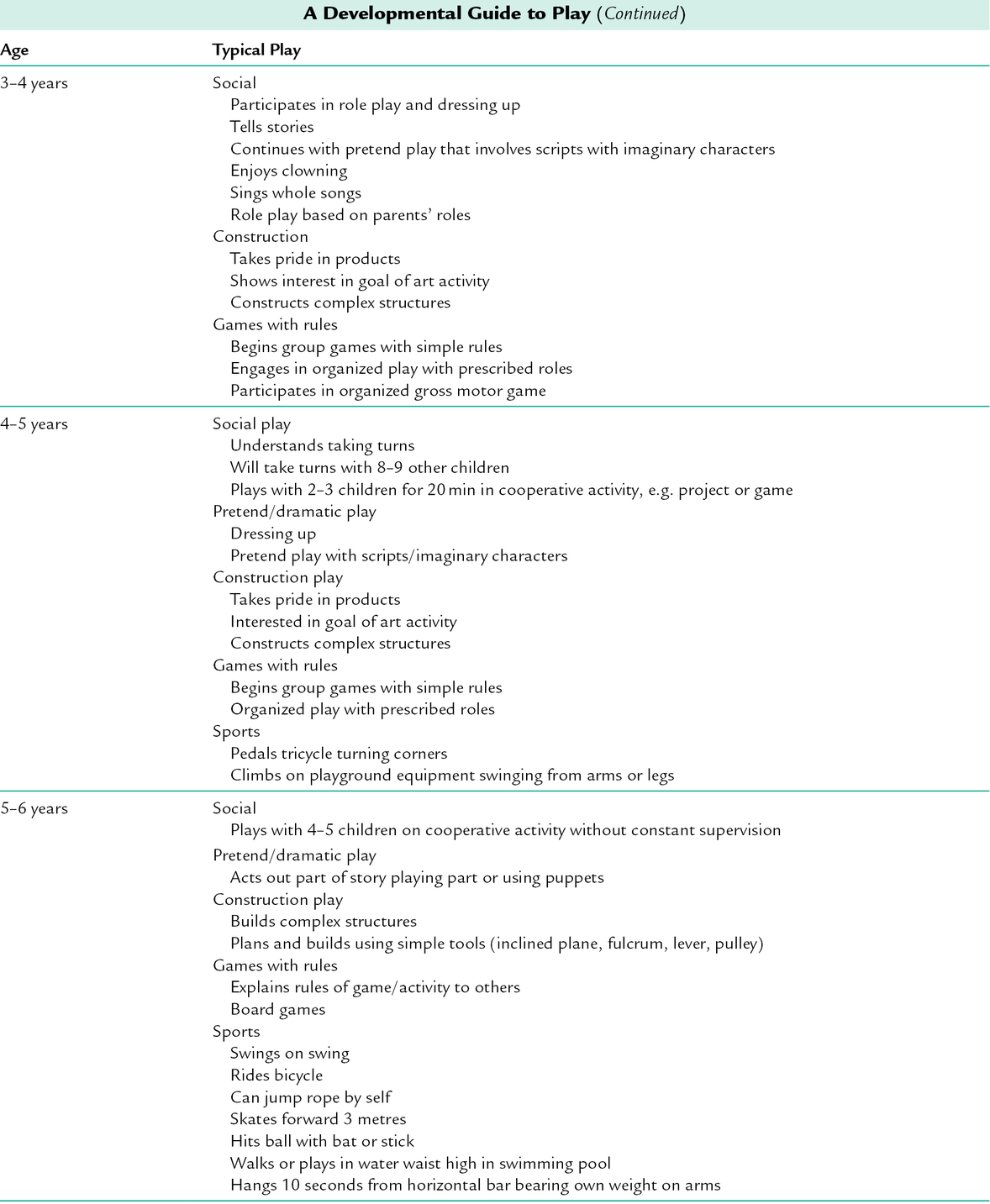

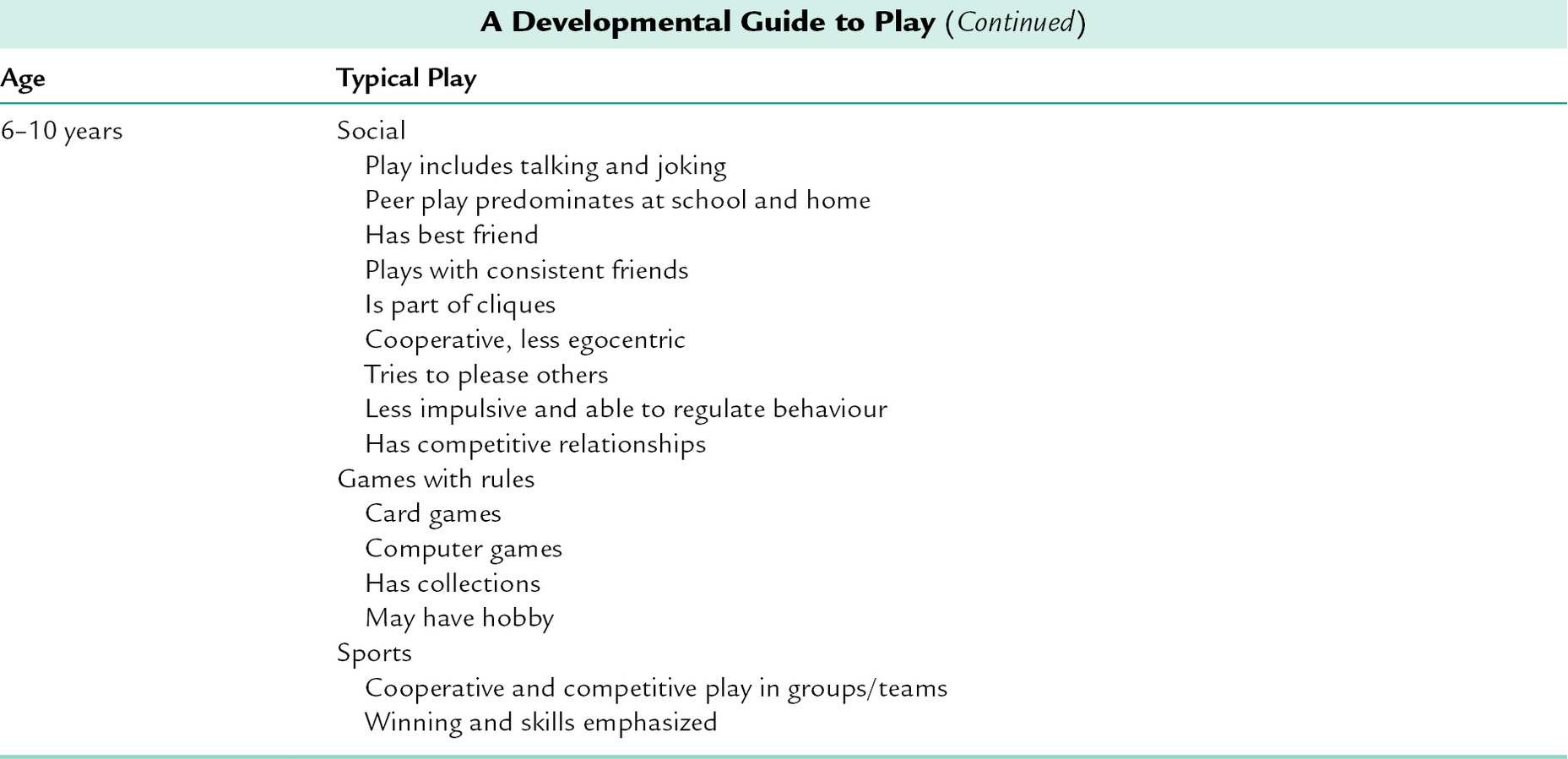

18 CHAPTER CONTENTS THEORETICAL UNDERSTANDINGS OF PLAY Play and Leisure as Occupations DEVELOPMENT OF PLAY OCCUPATIONS Occupational Development in Children and Young People Child-Initiated Pretend Play Assessment Play Skills Self-Report Questionnaire Cognitive Orientation to Daily Occupational Performance PLAY AND ATTENTION DEFICIT HYPERACTIVITY DISORDER Play is recognized as a universal right for every child in the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child (Article 31). Children have the right to rest and leisure, to engage in play and recreational activities appropriate to the age of the child. Participating fully in cultural and artistic life should be respected and promoted through the provision of appropriate opportunities for cultural, artistic, recreational and leisure activities. Children and young people’s play experiences influence their mental health status and overall development. Play is the context for the development of childhood friendships and enables children to learn about, and develop, occupational roles (Bundy 2012). Play deprivation can have a profound, negative effect on development and mental health. The presence of a mental health condition in either the child or parent can also effect the development of play occupations having further effects on the child’s mental health. In paediatric occupational therapy and mental health literature and practice, there has been a shift from the developmental significance of play and adaptation towards themes of socialization, play assessment and play as a primary occupation (Dennis and Rebeiro 2000). The delineation between the constructs of play and leisure has not been adequately defined and they are often lumped together as a single construct. Very young children are not usually considered to have leisure occupations and play is generally seen as the province of children. However, playing can be a meaningful occupation for adults as well. There is a shift from play to leisure activities with increasing age. Leisure is defined by the American Occupational Therapy Association (AOTA) as non-obligatory activity that is intrinsically motivated and engaged in during discretionary time (AOTA 2002). Townsend (1997) described the purpose of leisure to be for enjoyment, e.g. socializing, creative expressions, outdoor activities and games and sport. Passmore (1998) described three types of leisure: achievement, social and time-out: ■ Social leisure: The primary purpose of social leisure is to be with others and this supports competencies with relationships and social acceptance ■ Time-out leisure: The purpose of time-out leisure is relaxation which can have positive benefits in terms of providing rest but too much time-out leisure can have a negative effect as it is socially isolating and generally less demanding. While leisure occupations sit within the taxonomy of occupations for young people and adults, the notion of play can be seen as the primary occupation for young children. There is no universally accepted definition of play and it could be argued that defining an activity as play can only truly be done by the player themselves; however it has been suggested that there are some critical characteristics which delineate play from other occupations (Rigby and Rodger 2006). These include intrinsic motivation, process- not product-orientated, pretending, not governed by external rules and requiring active participation of the player (Rigby and Rodger 2006). Missiuna and Pollock (1991, p. 883) described free play as ‘spontaneous, intrinsically motivated, self-regulated, and requires personal involvement of the child. It includes exploration, mastery, decision making, achievement, increased motivation and competency’. Bundy (1991) echoed the defining aspects of play as being intrinsically motivated and internally controlled but she adds that it should also be free from objective reality. Creativity can be explored through play and is defined as: The innate capacity to think and act in original ways, to be inventive, to be imaginative and to find new and original solutions to needs, problems and forms of expression. It can be used in all activities. Its processes and outcomes are meaningful to its user and generate positive feelings. (Schmid 2005, p. 6) Creativity can be expressed through a wide range of occupations throughout life but for young children, play is the primary vehicle for creativity. Participation in play requires interaction with the ‘physical, social, cultural, economic and organizational aspects of the environment’ (Ziviani and Rodger 2006, p. 41). As well as facilitating play, the environment can be a barrier; it is necessary to consider the environment at different levels including individual, family, neighbourhood, community and society (see Table 18-1). TABLE 18-1 A Summary of the Environmental Influences on Play Occupations Children are often most aware of their physical environments and these have been of interest to researchers for some time. Susa and Benedict (1994) identified that the design of the outdoor play environment was an influencing factor in play. This study examined traditional playgrounds (slides, swings, seesaws) opposed to contemporary playgrounds (aesthetically pleasing timber connected to provide space for social interaction and graded challenges). It was found that contemporary playgrounds created more complex play including rockets, boats, castles and bridges. A further aspect of the play environment is the availability of toys or materials (Pellegrini and Smith 1998). The toys in Western culture are reported to include kitchen utensils, stoves, irons and ironing boards, toy phones, dress-up clothes, and toy miniatures (Johnson et al. 1999). Haight et al. (1999) provided a cross-cultural example of children in the Marquesas’ Islands pretending to paddle, canoe, hunt and fish using objects from the natural environment, while European-American children used superhero toy miniatures influenced by children’s movies. The social and economic environment can result in reduced play opportunities and, studies in orphanages in Romania showed that all the children had delays in cognitive and social functioning due to an impoverished environment (Kaler and Freeman 1994). The introduction of play sessions in such environments has been shown to significantly improve children’s development (Taneja et al. 2002). In the last decade, family environments have undergone significant changes with more mothers working, caregiving by grandparents, increased structured play and less free-time, financial pressures and parental separation and reconstituted families (Darlington and Rodger 2006). Parents’ and caregivers’ mental health status can also lead to reduced play opportunities for children and young people, for example persistent maternal depression has been associated with less time spent reading with a child, taking outings and trips to the park and playing indoors (Frech and Kimbro 2011). It is important when working with children and families to appreciate the family context and use family-centred practice. At the centre of family-centred practice are the beliefs that the family is the constant in the child’s life, knows the child best, wants the best for the child and will know the child in a way that a therapist will never be able to. This approach favours a collaborative parent–therapist partnership, where the therapist has technical expertise and the parents are experts on their child (Darlington and Rodger 2006). Play is universal, yet culturally determined and contextualized representing the values, beliefs, ethics, history and society that the individual belongs too (Roopnarine and Johnson 1994). Play both maintains and develops a culture’s identity and what is seen as play by one culture may not be by another. Through play, children learn to master their environment, learn society’s rules, practice skills, rehearse adult roles and understand cultural norms, symbols and attitudes (Drewes 2009). With the changing ecology of childhood, it is imperative that occupational therapists become conversant with the meaning and relevance of play in diverse cultures. There is a growing body of evidence to suggest that there are cultural differences seen in children’s play across Mexico, Africa, Asia, China, India, Korea, Japan, USA and Europe, as well as with indigenous populations (Drewes 2009). Haight et al. (1999) examined the differences in European-American and Chinese children’s play themes. They found that European-American children’s play emphasized individuality, independence and self-expression, while Chinese children’s play emphasized harmonious social interaction obtained through obeying, respecting and submitting to elders as well as adherence to rules and cooperation. A further example of Western and Eastern differences can be seen in a study by Farver and Shin (1997) who compared pretend play in preschool Korean-American and Anglo-American children. Theses authors found that in Korean-American society, it is culturally valued to be ready for school and therefore play had a greater number of teacher-directed activities and fewer opportunities to interact with peers during play. Anglo-American children were observed to wander free, interact and play with a greater range of toys, materials and curriculum. Further, cultural values can be seen in the link between play and gender. Early literature from Sutton-Smith et al. (1963) identified boys playing with soldiers, cowboys, spacemen and hunting, while girls played dolls, dress-up, school and actresses. Paley (1986) identified nursery as a place where sexual stereotypes begin. A theory is an explanation or understanding of a natural phenomenon; just as there are numerous definitions of play there are multiple and diverse theories of play. Classical understandings of play from the 19th and early 20th centuries were predominantly grounded in sociological and psychological theory and attempted to explain the existence and purpose of play. There are three classical theories of play: surplus energy, practice and recapitulation. ■ The practice theory of play: was formulated by Groos (1901). Groos posited the idea that play existed in children so that they could practice the instinctive behaviours necessary for survival. Groos also recommended forms and functions of play, which were experimental play, including sensory and motor activities and socioeconomic play, which included fighting, chasing, social and family games ■ Recapitulation theory: is about rehearsing activities of the child’s ancestors (Hall 1920). Hall viewed the function of play as cathartic rather than mastery and that during play, children played out the history of humankind, for example the throwing, running and hitting of cricket reflects a summary of hunting activity. These classical theories of play have been widely critiqued but form the basis from which the contemporary study of play has evolved. Contemporary accounts of play developed after the 1920s have been drawn from a range of knowledge bases but have often endeavoured to explain the role of play in child development. There are too many modern theories of play to discuss in detail in this chapter but they include Freud, who believed play had a role in children’s emotional development; Sears, who saw play as part of personality development; and Piaget, who proposed a theory of intellectual development through play (Johnson et al. 1999). These theories have served to further our understanding of child development and form important foundation knowledge for occupational therapists working with children and young people (Case-Smith and O’Brien 2010). In the early years of the occupational therapy profession, the ‘play spirit’ was considered essential for worthwhile life (Slagle 1922). Reflecting the prevailing trend in occupational therapy during the mid-20th century for a more medical and reductionist approach, Knox (2010) described how: Play in the early years of occupational therapy was used for a variety of purposes such as diversion, development of skills and remediation (p. 543) In the late 20th century, occupational therapy scholars started to reclaim play itself as an essential part of occupational therapy (Crepeau et al. 2009). Play is a primary occupation of childhood and is seen as having a unique value for its own sake beyond acquiring skills (Rigby and Rodger 2006; Bundy 2012). Play and play activities are not synonymous (Tobias and Goldkopf 1995). Play has to be child- rather than adult-directed, whereas occupational therapists often direct play activities to enable acquisition of specific skills, such as making choices or developing fine motor dexterity. Occupational therapy theory tends to group occupations into the broad categories of self-care, productivity, play and leisure. The Canadian Model of Occupational Performance and Engagement has a category of leisure which it describes as being for enjoyment, such as socializing, creative expressions, outdoor activities and games and sport (Townsend 1997; Townsend and Polatajko 2007). The Model of Human Occupation has a play and leisure category described as activities undertaken for their own sake (Kielhofner 2007). Recently, it has been suggested that these categories focus on the purpose of the occupation but do not capture the meaningfulness of the occupation (Hammell 2004). Hammell suggested we should consider the schema of doing, being, becoming and belonging, as conceptualized by Wilcock (2006). By doing play children acquire new skills and explore different experiences. This has the potential to build self-esteem, which is integral to mental health. Play can engender a sense of belonging to different social groups such as family, peers and wider society. Through play, children and young people can learn how to develop mastery over their environment, which gives it the potential to be a powerful therapeutic medium. ‘If play is the vehicle by which individuals become masters of their environments, then play should be the most powerful of therapeutic tools’ (Bundy 1991, p. 61). Passmore and French (2003) concluded that participating in leisure occupations has a significant and positive relationship with mental health, including self-efficacy beliefs. It has also been suggested that there may be a correlation between depression and participation in play and leisure activities, with engaging in active leisure activities having a potential protective factor against depression (Desha and Ziviani 2007). When children and young people are involved in setting goals for occupational therapy intervention, they frequently identify participation in specific play or leisure activities as a desired goal (Dunford et al. 2005). Occupational therapists believe that participation in meaningful occupations, including play, can promote health and wellbeing (WFOT 2012). Play has even been described as the work of children. Children tend to view tasks as work when they are directed to do the activity by an adult, if the skill is thought to be too difficult, or when the task is inhibited play (Chapparo and Hooper 2005). There are a whole range of occupations involved in parenting a child: being a playmate for your child could be viewed as one of the occupational roles. Parents need to learn how to play with their children and facilitate play as an occupation through providing suitable opportunities. A variety of factors can influence a parent’s ability to offer occupational opportunities for their child, including their own mental health status, experiences of being looked after as a child, parenting style, financial and time resources (Jaffe et al. 2010). Occupational therapists can enable parents to learn how to play with their child and provide appropriate play and leisure opportunities. This enables the child to explore their occupational role as a player, which is discussed further later in this chapter. Larson and Verma’s (1999) time use study found that adolescents’ time spent in various occupations was fairly consistent throughout Europe but contrasted with time use in developing countries. Children in many developing non-industrial countries spent more time performing household chores and work and consequently, less time in play and leisure activities. In Europe, the average time adolescents spent sleeping was 8–9 hours per day; TV viewing 1.5–2.5 hours per day; playing sports 20–80 minutes per day and other active leisure 10–20 minutes per day (Larson and Verma 1999). Time use studies are useful in providing some guidance around typical occupational balances for children and young people. Children develop the role of player alongside the roles of daughter/son, sibling, friend and student. The term player refers to a child’s engagement in different types of play over time and which reflect the context. For example, parallel play with a peer at the sand pit or constructional and solitary play with blocks at home (Rigby and Rodger 2006). Through the role of player a child engages with family and peers, learns to problem solve and uses their imagination. The role of player unfolds throughout childhood and adolescence as developing physical, cognitive and psychosocial skills enable them to expand their play repertoire. The development of play and the occupational role of player begins with sensorimotor exploration of their own bodies. Children discover their hands and feet. Then they start to explore their immediate environment and learn that they can cause things to happen around them. They will repeat actions to elicit pleasurable responses. Functional play enables children to explore the purpose of objects and their relationship to them. Social play initially occurs alongside others with cooperative play and turn-taking emerging during the second year. The number of other children they can play with increases with age. Once in school, peer relationships become important and friendships develop. Children learn to regulate their behaviour and consider others. They engage in games with increasingly complex rules and have competitive relationships. Learning the behaviours associated with different occupational roles is part of the socialization process and children develop social skills through play. As children grow older, they widen the number of occupational roles they have, including formal roles with specific expectations, such as being a member of a sports team. Development of player role behaviours can be a vehicle for testing and experimenting with different roles in preparation for adult life (Case-Smith and O’Brien 2010). Since the last edition of this book, occupational therapists have challenged the assumptions and relevance of existing play theories (see above). Occupational science has facilitated an occupational perspective of play, which embraces the complex nature of play (Stagnitti 2004). Occupational therapists acknowledge a range of theoretical understandings about play but are identifying the limitations of interpreting play only through its physical, cognitive and psychosocial components. In accordance with this view, Humphry (2005) reported that there has been an over-reliance on play theories that provide an organismic subsystem view. Occupational therapists need to appreciate the multiple understandings of play which take into account the occupational nature of people. An occupational perspective of play requires an evolutionary, ecological and humanist approach (Wilcock 2006). The use of occupational science helps occupational therapists to consider play as a dynamic interaction between the child, their environment and the occupation. Occupational therapists have begun to develop a holistic understanding of play from an occupational perspective. An example of this is the concept of playfulness. Bundy, an Australian occupational therapist, proposed an interactionalist perspective called playfulness, which is ‘the disposition or tendency to play’ (Cordier and Bundy 2009, p. 46). In this theory there are four key concepts: 2. Internal control concerns the control that players have over their play. Children make decisions during play such as what the rules are during a game of tag. This gives them a sense of being in charge 3. Freedom from the constraints of reality means how close to object reality the play will be. For example children use boxes to represent cars and houses when they play families with dolls and teddies 4. Framing refers to the ability of players to read social cues and interact. This aspect of playfulness reflects how a child expresses cultural knowledge, framing it within a common understanding of what is play and what is happening during the play. Bundy also utilized the environment in her model suggesting that this can either impede or facilitate play with optimal environments being safe, allowing adaptation, promoting involvement and supporting motivation and mastery (Cordier and Bundy 2009). Playfulness can be disturbed when any of the key elements are not present or when the environment does not support play. Children with autism can have difficulty with the suspension of reality and are therefore susceptible to deficits in playfulness. Children and young people’s play occupations occur within their own unique context through a dynamic interaction between the person, the play occupation and the environment (Law et al. 1996; Wiseman et al. 2005). Children engage in different types of play; exploratory, functional, social, pretend/symbolic, dramatic, constructive, imaginative, creative, rough and tumble, games with rules and sports-related. Child development can be seen as emerging from the dynamic interaction of multiple systems and sub-systems within the child such as biomechanics, central nervous system, physiology, cognition, motivation, experiences; the environment – physical, social, cultural and occupational (Thelen 1995). Developmental changes in motor, cognitive and psychosocial domains interact dynamically with the child’s experiences to influence their play development. However, occupational therapists need to understand development in a way that goes beyond milestones and developmental norms to development of the knowledge and skills required to enable children to fulfil their occupational roles. Play needs to be viewed from the child’s unique perspective that is shaped by their environment and culture. Occupational therapists should also consider all aspects of the environment as important when understanding children’s play. Although less obvious, home, neighbourhood and community environments have a significant impact on play, including the expansion of sedentary play activities, increased urbanization, demise of playgrounds, growth of apartment living and concerns about safety. Writing about the loss of a neighbourhood pond in Canada, Manuel (2003) used an occupational science perspective to describe how the physical pond environment facilitated play occupations including ice skating, frog catching and fishing. Manuel also highlighted the impact of the social and cultural environment including neighbourhood skating parties and community spectators. There are a number of proposed models or theories of child occupational development. Humphry (2005) has proposed the Model of Processes Transforming Occupations (PTO) as a way to understand how children’s occupations develop, rather than how children’s abilities develop. The PTO can be applied to children’s occupations, which are described as ‘activities that children find interesting or pleasurable and want to do or do because others manifest value in their doing so’ (Humphry 2005, p. 38). The PTO applies dynamic systems theory to play, meaning that a child’s intrinsic capacities (physical, cognitive and psychosocial skills) self-organize into a performance pattern for that play situation; these intrinsic capacities are interdependent and dynamic, so should not be separated (Humphry 2002). The focus is on the interaction of the child, the environment and the occupation, which reflect the occupational meaning. The PTO has three clusters which can be used to explain participation in play occupations: 2. Social transaction in developing occupation: This second cluster refers to the idea that being involved in a co-occupation contributes to the development and adaptation of the occupation. Two children bring different performance patterns and skills to a joint play occupation, such as playing dress-up, which creates a new co-constructed occupation and new meaning 3. Self-organizing processes underlying transformations in occupation: This final cluster applies dynamic systems. Intrinsic capabilities within the child are assembled to enable occupational performance for that play occupation. These capabilities are reorganized as an occupation changes but repeated use through occupation enables enhanced performance. The Process for Establishing Children’s Occupations (PECO) (Wiseman et al. 2005) is a further example of a theory of occupational development in children. The PECO was developed from a qualitative study of children and young people’s engagement in occupations and focuses on the development of childhood occupations rather than the development of the individual. The authors described two themes which emerged from 12 in-depth interviews. The first theme includes the reasons why children do the things they do (opportunities, resources, motivations, parental views and values), and the second theme identifies a process by which children’s occupations become established (innate drive, exposure, initiation, continuation, transformation, cessation and outcomes). The PECO was developed from an exploratory study but offers an initial representation of how, and what, influences the development of occupations in childhood. Case-Smith (2010) has also detailed the development of children’s occupations. Table 18-2 is a quick reference guide to play occupations at different ages.

Play

INTRODUCTION

Environment and Play

Environment

Definition/Example

Physical environment

The natural environment such as the terrain and climate; the built environment including the design of buildings and objects within it such as toys

Social environment

Expectations and attitudes of social support including family, friends and care-givers

Cultural environment

Societal norms including beliefs, customs, social behaviours, attitudes and expectations

Economic environment

Availability of resources such as finances at both a local and societal level

Organizational environment

Structures that mediate resources including the government, policies, managers

Culture and Play

THEORETICAL UNDERSTANDINGS OF PLAY

Classical Play Theories

Contemporary Play Theories

OCCUPATIONAL THERAPY AND PLAY

Play and Leisure as Occupations

Developing as a Player

Occupational Play Theories

Playfulness Theory

DEVELOPMENT OF PLAY OCCUPATIONS

Occupational Development in Children and Young People

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree