16 Presurgical Psychological Screening William W. Deardorff Someone once said, “There is no medical condition that cannot be made worse by surgery,” and this certainly holds true in the area of spine. Even though technologic advances in the area of spine surgery have been significant, numerous patients will undergo spine surgery for chronic low back or neck pain without benefit, or even become worse.1–9 Several studies have demonstrated that purely “structural” issues (e.g., preoperative diagnostic severity, success of arthrodesis) are not highly correlated with clinical outcomes.1,7,9 Technical failure rarely explains a diminished surgery result9; rather, poor patient selection due to psychosocial variables appears paramount.1,9 Several psychosocial variables have been found to be predictors of clinical and functional outcome to spine surgery, especially for chronic pain conditions (Table 16.1).1,7,9 There are few unequivocal predictors, however, and these often explain a relatively low proportion of the variance in outcome.9 To address this problem, biopsychosocial decision-making algorithms have been developed that take into account multiple predictor variables, including demographic, lifestyle, biologic, work, psychosocial, and medical factors.1 Comprehensive presurgical psychological screening prior to spine surgery is an extensive process usually completed by a psychologist with special expertise in this area. It is beyond the scope of this chapter to review the literature supporting psychological screening in spine surgery, and the reader is referred elsewhere.1,9 Rather, the brief screening tools that the spine surgeon can use in his or her practice to identify patients at risk for poor outcome are the focus here. The most robust and easily assessed biopsychosocial variables will be reviewed and a rapid assessment protocol presented (the Brief Presurgical Screening [BPSS]). A patient’s appropriateness to undergo presurgical screening can be conceptualized as being on a continuum from not necessary to critical. As pointed out by Carragee,10 conditions such as metastatic cancer to the spine or idiopathic scoliosis progression are unlikely to have a significant psychosocial component affecting surgical outcome, and presurgical screening is not necessary. On the other hand, a disabled, work-injured, chronic low back pain patient with depression, other psychosocial issues, and equivocal structural findings, should certainly undergo presurgical screening. Between these two extremes, the need for the screening becomes less clear. The predictive power of presurgical screening in patients undergoing surgery for straightforward conditions such as a lumbar disc herniation has not been established and is likely weak.10,11 In this patient population, although psychological distress may be present preoperatively, it often decreases postoperatively, presumably due to the fact that the nociceptive input has been successfully remedied. In general, if a pain generator can be clearly identified, there is a high correlation between subjective and objective findings, there are minimal psychosocial issues present, and the surgery is minimally invasive, then a presurgical screening is not necessary. As these variables change, presurgical screening becomes more important.

Presurgical Screening

| Biological/lifestyle |

| Age |

| Gender |

| Smoking |

| Weight |

| Exercise |

| Substance use |

| Work related |

| Low income |

| Low education |

| Low job level |

| Workers’ compensation |

| Job dissatisfaction |

| Heavy job |

| Sick leave |

| Psychosocial |

| Pain sensitivity |

| Depression |

| Anxiety |

| Anger |

| Fear avoidance |

| Coping strategies |

| Personality features |

| Disability payments contingent on pain |

| Family reinforcement |

| Other psychological disorders |

| Involvement in litigation |

| Medical |

| Number of affected levels |

| Duration of symptoms |

| Clinical severity |

| Previous spine surgery |

| Other (nonspinal) medical problems |

Predictor Variables

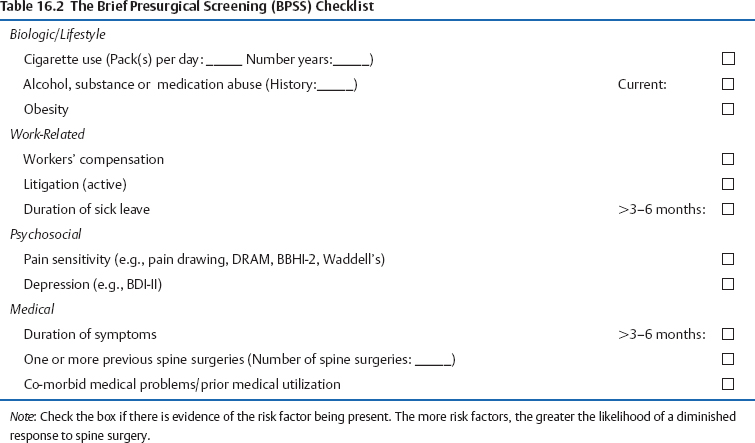

A brief presurgical screening should assess those variables that (1) have consistently been shown to be predictive of poor spine surgery outcome, and (2) are easily assessed within the context of a spine surgery practice. Lengthy presurgical screening procedures (e.g., interview, record review, and psychological testing) are more appropriately done by the psychologist upon referral from the surgeon once the patient has been identified by the initial presurgical screening. In designing a BPSS, the most important variables from each of the four major predictor categories are assessed (Table 16.2).

Biologic and Lifestyle Variables

Although several biologic, demographic, and lifestyle variables have been investigated (Table 16.1), most have shown inconsistent predictive power when assessed independently.1,9 Of these variables, cigarette use, alcohol and substance use, and obesity are the most useful to include in a brief screening.

Cigarette use

Smoking is a frequently assessed predictive variable especially related to outcome to spinal fusion.1,5,9,12,13 Research suggests that it is a predictor of poor outcome for two reasons: (1) habitual nicotine use is thought to decrease revascularization of the bone graft, slow healing rates, increase the risk of infection, and increase the risk of pseu-darthrosis1,13,14; and (2) cigarette use has been correlated with other variables that may exert their own negative influence on spine surgery outcome such as “unhealthy” lifestyle behaviors (e.g., lack of exercise, poor nutrition, alcohol use, etc.), lower socioeconomic status, and heavy physical job demands.5,9,15,16 If a spinal fusion is being considered for a patient there are no clear guidelines about preoperative cessation of smoking.17,18 Certainly, the longer a patient is abstinent from smoking preoperatively, the more likely he or she will be able to stay abstinent during the lengthy and often-stressful postoperative recovery period.

Alcohol and Substance Abuse

It is difficult to accurately assess alcohol or substance abuse in spine surgery candidates because many patients are reluctant to reveal this type of information.1 As a result, few studies have directly examined the effect of alcohol or substance abuse on spine surgery outcome. Excessive alcohol use has the potential to negatively impact a patient’s recovery from spine surgery in several ways, including slower wound healing, sleep disruption, increased depression and anxiety, increased likelihood of smoking due to lowered impulse control, poor nutrition, amplified endocrine changes in response to surgery, and synergistic interactions with medications.1,19,20

Substance abuse in spine surgery candidates might include use of illicit drugs (current or history) or abuse of prescription medications. With the increased acceptance of long-term opioid treatment in the management of chronic pain conditions, evaluation of the possible abuse of prescription medications becomes more difficult. As part of the BPSS, the surgeon should be aware of the following questions: what is the overall level of pain medication use, is the patient showing a need for escalating dosages, has the medication actually improved patient function, is the patient taking the medications as prescribed (compliance or noncompliance), is there any evidence of abuse of prescription medications (e.g., doctor shopping, frequent emergency room visits, getting medication from illegitimate sources), are all the patient’s medications related to the chronic pain problem being managed by one physician, and is the patient under an opioid treatment contract? If there is any evidence of alcohol or substance abuse, or if the patient has been on high doses of opioids for quite some time, it is most prudent to address these issues prior to surgery.

Obesity

Body weight has not emerged as a consistent predictor of spine surgery outcome,9 but recent studies have demonstrated an increased risk for surgical site infection in spinal surgery patients who were morbidly obese.21,22 Obesity has been found to contribute significantly to several variables predictive of poor outcome to spine surgery.23 In a workers’ compensation population, it has been correlated with greater compensation costs but not medical costs.24 Elderly obese patients undergoing decompressive laminectomy and/or discectomy (fusion cases excluded), have demonstrated a greater level of being “very dissatisfied” with the surgery outcome, higher pain ratings, and lower activities of daily living relative to the nonobese comparison group.25 Interestingly, studies have generally found no differences between obese and nonobese spine surgery groups in terms of duration of surgery, blood loss, duration of hospitalization, and most clinical outcomes.25,26

The inconsistent findings of these studies are likely due to the marked differences in patient population variables (age, work status, etc.), definitions of obesity, and type of spine surgery being investigated (fusion versus nonfusion procedures). As a predictor of poor spine surgery outcome, obesity probably interacts with these other factors. As such, it is conceptualized as a variable to be assessed within the context of other more powerful predictors (e.g., disability, litigation, psychological distress).

Work-Related Variables

Work-related variables, as a group, demonstrate some of the strongest correlations with poor spine surgery outcome. Those variables amenable to a BPSS include workers’ compensation, litigation, and extended disability duration.

Workers’ Compensation

A great number of studies have demonstrated that involvement in the workers’ compensation system predicts a poorer outcome to spinal surgery.1,9 Although it might be concluded that this is related to financial incentives for staying disabled, it is more likely due to the various difficulties experienced by the disabled worker, including such things as financial distress, loss of identity related to the job, an adversarial relationship with the employer and insurance carrier, delays in treatment, having to “prove” one is injured, among other things. The longer the patient is off of work, the more time a “system-induced functional disability syndrome” has to develop.27 Although workers’ compensation status is a significant predictor of spine surgery outcome, studies suggest that this effect is mediated by other variables such as time off of work, legal representation, job satisfaction, and so forth.1,9,27 For the patient who loves his job and is undergoing a spine surgery for a disc herniation that occurred at work just 2 months prior, workers’ compensation status will rarely be a predictor of poor outcome.

Litigation

Another predictor variable that has consistently been linked to poorer spine surgery outcome is litigation status (related to workers’ compensation, personal injury, or disability benefits).1,5,7,9,24 Although one might surmise that this is due to symptom exaggeration for secondary gain, it must be assumed that the spine surgery is being recommended because some evidence of pathophysiology has been identified.5 The litigious patient might very well do poorly because of increased somatic sensitivity to pain as a consequence of financial incentives and social-contextual variables.5,9

Duration of Sick Leave

Lengthy preoperative sick leave is a consistent predictor of diminished response to spine surgery including global outcome, overall satisfaction, back-specific function, and return to work.1,3,9,28,29 Longer duration of sick leave allows for development of the functional disability or chronic pain syndrome, which is probably the reason for the poorer spine surgery outcomes.1,27

Psychological Factors

Psychological factors are among the most frequently investigated predictive variables for spine surgery outcome. Some of the common psychological variables assessed include pain sensitivity, depression, anxiety, anger, fear avoidance, severe psychopathology, and various personality disorders or features.1,9 Psychological predictive variables are often assessed through the use of psychometric testing, and the most commonly researched test has been the Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory (MMPI/MMPI-2).30,31 It is beyond the scope of a brief initial presurgical screening to include an MMPI-2 (567 questions and 1.5 hours to complete), although it is often used as a component of a comprehensive presurgical screening.1 Ideally, a BPSS would include some very brief questionnaires that assess the same predictive psychological variables captured by the MMPI-2 and other more comprehensive tests. Although many psychological variables have been identified as predictive of poor spine surgery outcome, pain sensitivity and depression have received the most attention.

Pain Sensitivity

Of all the psychological factors investigated, those falling under the rubric of “pain sensitivity” have shown the most consistent predictive power.1,9 Pain sensitivity might be defined as a patient’s propensity to display pain behaviors beyond what would be expected due to nociceptive input and objective findings. Pain sensitivity also encompasses the idea of how much the patient is “suffering” due to the pain; or, the emotional contribution to the patient’s perception of pain and level of disability. Pain sensitivity includes such concepts as heightened somatic awareness, fear of movement (kinesophobia), somatic anxiety, and general psychological distress (but not necessarily depression). Given this conceptualization of pain sensitivity, it is not surprising that any test that assesses some component of this construct might predict poor spine surgery outcome. This is probably why many tests (aside from the MMPI-2) have been shown to correlate with spine surgery outcome, including the Distress Risk and Assessment Method (DRAM),29,32 the Dallas Pain Questionnaire,33 the Mental Component Score of the SF-36,12 and the Waddell Non-Organic Signs,1,34 among others.

The pain drawing is another purported assessment of pain sensitivity. Pain drawings are hypothesized to identify the psychological contribution to a patient’s pain and are scored in several ways.35 Pain drawings that are deemed “abnormal” or “nonorganic” (unexplainable pain distribution) are thought to identify patients with a greater psychological component to their pain, although this conclusion has been contested in a recent review.35 The pain drawing has been investigated as a predictor variable for spine surgery outcome but the results are inconsistent.36 Even so, the pain drawing is easily administered; when it is grossly abnormal, it might be a useful piece of information to incorporate with other screening variables.1

Assessing pain sensitivity as part of a BPSS might be done in several ways. Certainly, the pain drawing can be used adjunctively, but not as a stand-alone predictive test. The DRAM system was developed as a measure of distress in back pain patients32 and has been used as a rapid presurgical screening tool.29 The DRAM consists of a modified version of the Zung Depression Inventory (ZDI; 23 items) and the Modified Somatic Perceptions Questionnaire (MSPQ; 22 somatic items). The DRAM takes ~10 minutes to complete and places patients into one of four categories based upon classification rules for the results of the two tests: Normal (N), at Risk (R), Distressed-Depressive (DD), and Distressed-Somatic (DS). Patients in the distressed groups (DD, DS) have been found to have a diminished response to spine surgery,29 although results did not always rise to the level of statistical significance.11,37 Research suggests the DRAM may be most useful in screening of chronic back pain patients rather than more acute conditions.10,11

Another instrument that is emerging as a possible choice for quickly assessing pain sensitivity and other predictive variables is the Brief Battery for Health Improvement version 2 (BBHI-2).37 This 63-item test takes ~10 minutes to complete and was developed for use with medical patients. The BBHI-2 yields scores for six scales covering three content areas: validity (defensiveness), physical symptoms (somatic complaints, pain complaints, functional complaints), and affective symptoms (depression and anxiety). The BBHI-2 assesses many areas that have been found to be predictive of poor outcome to spine surgery (e.g., somatic complaints, pain complaints, depression, anxiety); however, it has not been directly tested in any spine surgery outcome studies.38

Depression

Major depression occurs frequently in patients with chronic spine pain39,40 and has been found to predict poor spine surgery outcome in some studies5,6,23,29 but not in others.3,11,41 These inconsistent findings are likely due to several reasons.1 Patients with protracted depressive symptoms (either antedating a chronic pain problem or associated with it) may be less likely to have their psychological symptoms resolve after surgery than a patient with depression that is more acute and reactive to the pain. This has been substantiated in recent studies suggesting that spine pain patients with shorter duration of symptoms and lack of other psychosocial risk factors might show preoperative depression in response to the pain (“reactive depression”) but this resolves after successful surgery.10,11 If the DRAM or BBHI-2 is used to assess pain sensitivity, a depression score is included in the test. Other rapid measures of depression are the Beck Depression Inventory-II (BDI-II) and the BDI-PC (BDI for primary care).42

Medical Variables

Few studies have identified medical factors that are consistent and unequivocal predictors of poor spine surgery outcome. Of the predictive variables investigated (Table 16.1), duration of symptoms, number of previous spine surgeries, and associated medical problems have reasonable support in the outcome studies and are most amenable to a BPSS.

Duration of Symptoms

Duration of symptoms has been measured directly and as a component of other predictor variables (e.g., length of disability, workers’ compensation, sick leave).19 Consistent with theories on the development of the chronic pain syndrome,27 the longer duration of symptoms allows for other psychosocial issues to emerge that adversely impact spine surgery outcome (e.g., physical deconditioning, psychological distress).

Number of Previous Spine Surgeries

It is estimated that the failed back surgery syndrome occurs in 10 to 40% of all spine surgeries,43 and the probability of good surgical outcome decreases with each successive surgical intervention.1,9 However, there is evidence that patients who have responded well to a previous spine surgery are more likely to do better with additional surgery, assuming a clear pain generator has been identified and is amenable to surgical intervention.1,9

Associated Medical Problems

This predictive variable category is assessed by evaluating prior medical utilization and comorbid health conditions. A myriad of studies have demonstrated diminished spine surgery outcomes in patients with a history of many prior illnesses and nonspine surgeries. This may be due to the fact that prior medical utilization reflects sensitivity not only to pain, but also to physical symptoms in general.1 Comorbid medical conditions and poor general health might impact spine surgery outcome due to such things as problems with wound healing (e.g., with diabetes) or postoperative rehabilitation (e.g., with other joint problems or systemic issues such as fibromyalgia).

The Brief Presurgical Screening

As part of the surgery decision-making process, the BPSS can help avoid the creation of a failed back surgery syndrome case. Table 16.2 summarizes those variables that are amenable to rapid screening and have, as a group, been shown to have reasonable predictive power. There are no empirical guidelines or scoring criteria for the checklist; however, the research suggests that the greater the number of risk factors the more likely the spine surgery outcome will be diminished. There are some risk factors that the surgeon might want to “weight” more heavily than others. For instance, according to the research, a patient who is in the workers’ compensation system, represented by an attorney, has been on disability for 4 years, and is facing a third surgery is at high risk for failure regardless of any other variables.

Disposition of patients identified as high risk for clinical failure might include (1) referring the patient to a qualified psychologist for more extensive screening, and possibly pain management or preparation for surgery treatment1,44; (2) helping the patient successfully address the risk factors and then reassessing for surgery at a later date (e.g., detoxification, quitting smoking, weight loss, treating a clinical depression, etc.); and (3) avoiding spine surgery and referring the patient to an appropriate functional restoration program.3,45

References

6. Franklin GM, Haug J, Heyer NJ, et al. Outcome of lumbar fusion in Washington state workers’ compensation. Spine 1994;17:1897–1903

18. Porter SE, Hanley EN. The musculoskeletal effects of smoking. J Am Acad Orthop Surg 2001;9:9–17

44. Deardorff WW, Reeves JL. Preparing for Surgery. Oakland: New Harbinger Press; 1997

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree