11 Primary and Secondary Headache

Primary Headache Disorders

Migraine

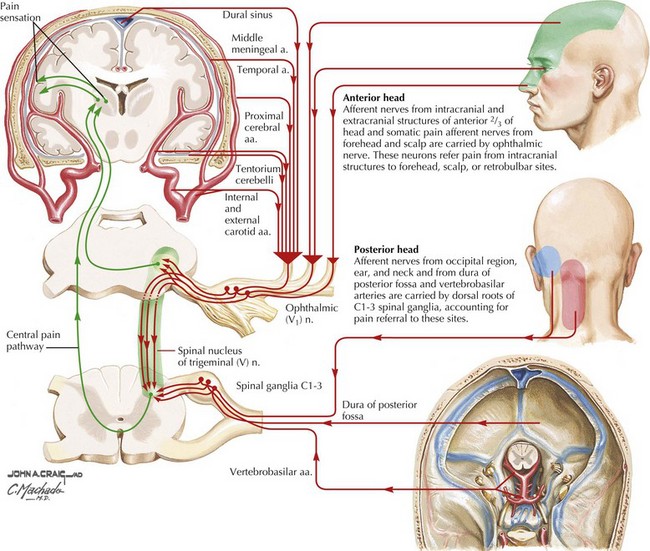

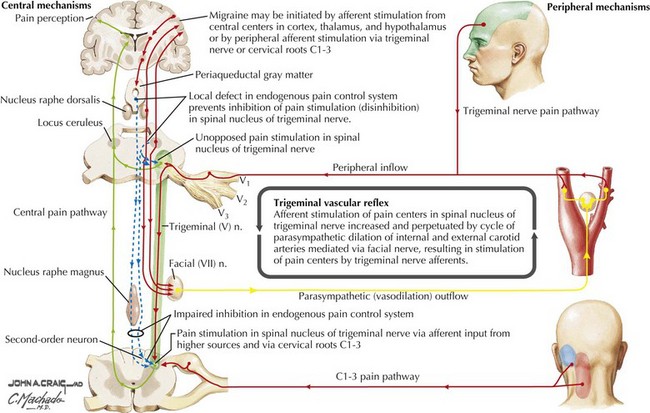

Migraine pathophysiology includes a combination of cortical hyperexcitability and discharge followed by cation and neurotransmitter release with secondary activation of trigeminal pathways, and subsequent release of vasoactive neuropeptides and proinflammatory substances. These promote meningeal blood vessel dilatation and neurogenic inflammation in the primary pain nerve endings of the head lying in the arteries, leptomeninges, and nasal sinuses (Figs. 11-1 and 11-2). In migraine with aura, the pathophysiology of the aura is thought to be related to slow neuronal discharge of the cortex in a sequential pattern or “spreading depression” followed by a concomitant decrease in cerebral blood flow.

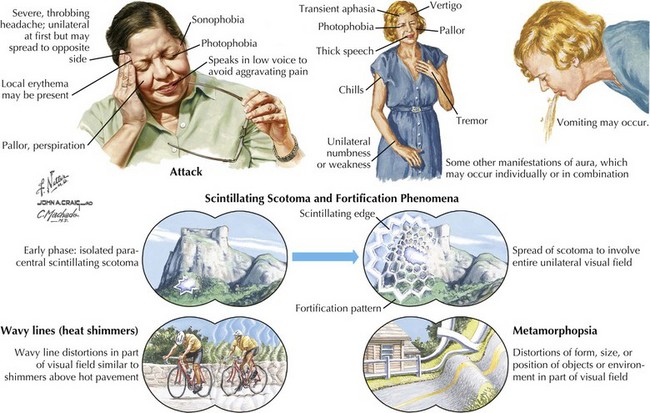

Patients with migraine often have prodromal symptoms that herald the oncoming headache. These include fatigue, thirst, anorexia, fluid retention, food cravings, gastrointestinal symptoms, and emotional or mood disturbances such as irritability, elation or depression. Approximately 15% of migraine patients have an aura preceding the pain phase. This presentation known presently as migraine with aura (formerly classic migraine) comprises focal neurologic symptoms, most commonly visual (>95% of all auras), that typically evolve and then regress over minutes before headache onset. These visual phenomena can occur in a homonymous or hemifield distribution. Typical migraine scotomata include scintillating flashes or stars (phosphenes) and geometric patterns known as fortification spectra (Fig. 11-3). Auras may also involve sensory, motor or rarely higher cortical pathways, including language. Most auras develop slowly over several to 20 minutes, last less than 1 hour, and may spread over different anatomic areas. For example, the patient may initially experience numbness in the fingers that gradually spreads up the arm to the face and sometimes even down the leg. In some individuals, the auras may not be necessarily followed by the headache phase. Less commonly, the aura phase consists of complex symptomatology with a more abrupt onset. For example, in basilar artery migraine, symptoms may include dysarthria, vertigo, ataxia, diplopia, hearing deficits, and even altered mentation or loss of consciousness. In confusional migraine, cognitive deficits are more prominent. Ocular nerve palsies are the hallmark of ophthalmoplegic migraine. Hemiplegic migraine is associated with variable but prominent unilateral weakness, and there is often a family history with an inherited voltage-dependent calcium channelopathy.

Management and Therapy

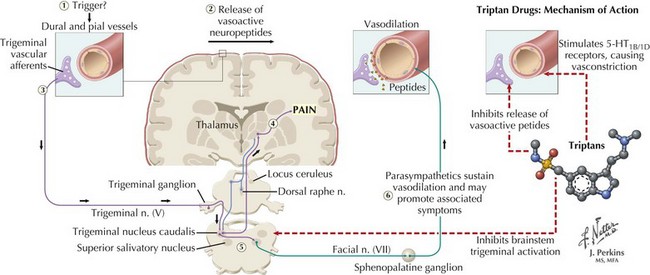

However, in patients with more severe disabling migraines, oral, injectable, intranasal, or quick-dissolve sublingual serotonin 1B/1D receptor agonist (“triptan”) preparations are the medications of choice. Their success is attributed to the multiple sites of action triptans have on the migraine cascade that include decreasing cortical hyperexcitability, decreasing tissue leakage of neuropeptides and blocking their dural neurovascular effects, tempering trigeminal afferent input, suppressing or down-regulating brainstem activation, gating thalamic pain response, and finally countering progressive vasodilation (Fig. 11-4). The rapidly acting triptans include almotriptan, eletriptan, rizatriptan, sumatriptan, and zolmitriptan. The longer acting triptans include naratriptan and frovatriptan. These preparations are also recommended for patients with milder migraines that are not initially disabling but are refractory to simple analgesics. Butalbital, ergotamine, and isometheptene/dichloralphenazone preparations are also commonly used for abortive therapy. When the above-mentioned therapeutic options are ineffective in patients with the most severe migraines or if those treatments are contraindicated, nonnarcotic treatments, such as ketorolac and antiemetics, are attempted. When these fail, opiate-category medications are often used, primarily in the emergency room. However, the possibility of sedation and, more importantly, subsequent overuse and dependence must be considered.

Cluster Headache

Clinical Vignette

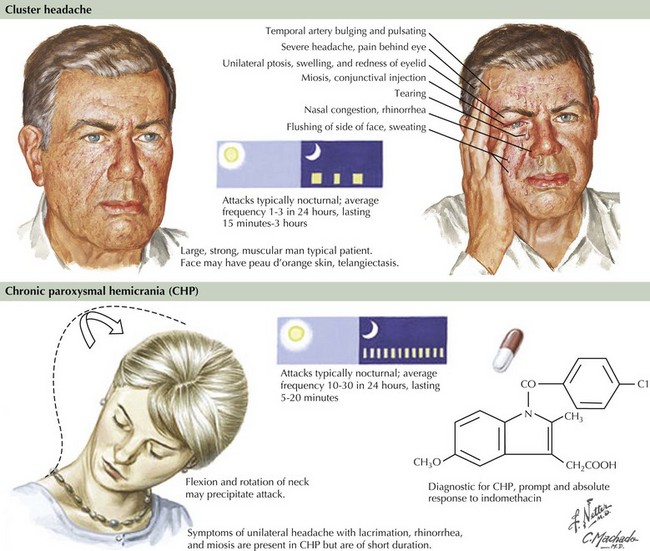

The distinctive clinical features, as summarized in the clinical vignette, assist in diagnosing cluster headaches (Fig. 11-5). The underlying pathophysiology is related to activation of the trigeminal vascular and parasympathetic systems. The first two divisions of the trigeminal pathway are more commonly involved. Recent positron emission tomographic scan studies by Goadsby and colleagues revealed activation of the medial hypothalamic gray matter, an area involved in the control of circadian rhythms. It is felt that dysfunction of neurons in this area leads to activation of a trigeminal-autonomic loop in the brainstem. These pathophysiologic mechanisms would explain the cardinal symptoms of cluster headache that include the episodic/circadian nature of the attacks, the distribution and quality of pain, and associated autonomic symptoms.

Other Trigeminal Autonomic Cephalgias

Paroxysmal Hemicranias

These are unusual primary headaches—unilateral and short-lived (2–45 minutes), which occur in a chronic or episodic manner. Typically, the pain has a severe throbbing or boring quality and often recurs several times during the same day. These headaches are associated with ipsilateral cranial autonomic dysfunction but, unlike cluster headaches, occur more often in women than in men. Furthermore, these headaches have daily recurrences and tend not to conglomerate over a few days such as in cluster headaches. They usually respond well to 25–50 mg indomethacin 2–3 times daily for at least 48 hours. These headaches by definition are “indomethacin responsive,” and a trial is always warranted if there are no medical contraindications to its use (Fig. 11-5). There are reports of good response as well to acetazolamide. Calcium channel blockers, such as verapamil, are used for long-term prophylactic treatment.