Primary Malignant Tumors of the Cervical Spine

Stefano Boriani

Stefano Bandiera

Luca Boriani

James N. Weinstein

A low rate of occurrence, nonspecific symptoms, and sometimes slow evolution (1,2) frequently result in late diagnosis of primary malignant tumors of the cervical spine. Computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) can allow early detection of lowgrade malignancies (3), but it is uncommon to order these expensive diagnostic studies in the face of neck pain unaccompanied by neurologic deficit. Therefore, these conditions are mostly discovered when pain becomes intractable or when neurologic or anatomically related symptoms (like dysphagia) occur (1). The high-grade malignancies, such as osteosarcoma, Ewing’s sarcoma, and malignant fibrous histiocytoma, are typically detected earlier because of their more rapidly evolving clinical picture: they are expansive and involve more anatomic “compartments” at first detection (4). Excluding metastases and plasmacytomas, most bone tumors of the cervical spine are benign (1,2). Malignant hemoglobinopathies are more common than primary malignant bone tumors in the cervical spine, but the role of surgery in these conditions remains controversial.

Surgical treatment of primary malignant bone tumors of the cervical spine, when indicated, is difficult and frequently requires multiple approaches. The peculiarities of the surgical anatomy of the neck—characterized by close proximity of the spine to vital neurovascular and soft tissue structures—make it difficult to plan oncologically appropriate surgical treatment (5). Only the most recently published literature contains reports of en bloc surgical resection of neoplasms in the cervical spine (6, 7, 8, 9, 10 and 11). Intralesional surgery, combined with modern techniques of radiation therapy, or radiation alone (when high doses can be delivered without undue radiation effects on the spinal cord and other radiosensitive structures), is more frequently an option (12).

Advances in anesthesiology have made it possible to perform these often time-consuming and bloody procedures more safely. One example is performing a dorsal approach to the cervical spine in the sitting position (13). Unlike benign lesions of the cervical spine, malignant processes such as chordomas are seen more often in elderly patients, adding further anesthesiologic risk and associated morbidity.

Often, the rapid evolution or the late discovery of such lesions makes it difficult to identify the site of origin within the vertebra of primary malignant tumors of the cervical spine. These primary malignancies can involve the entire vertebra and the surrounding tissues at the time of discovery. In this chapter, we discuss the role of imaging techniques, oncologic surgical planning, and the expected outcome of different histologic tumor types by using the published literature and our institutional experience.

A word of caution is in order. These tumors in and of themselves provide even the most skilled clinician with a diagnostic and therapeutic challenge. A multidisciplinary approach is needed to provide the best opportunity for surgical success. Institutions without significant experience in the diagnosis, staging, and treatment options in these cases should refer them to a center where such experience exists. As with most tumors, the coordinated effort of an experienced intensive care unit is important to the management of such cases. Finally, it is often difficult to make definitive treatment recommendations because each tumor in every patient is different, and generalities or algorithmic approaches to such cases do not have evidence-based support. Cancer, in and of itself, is difficult for patients and their families to deal with, but “shared decision making” with patients in such cases is essential. All options must be considered and the patient’s values entered into the treatment equation.

POPULATION

From the archives of C.A. Pizzardi and Rizzoli Institutes in Bologna (Italy), 1,109 cases of bone tumors of the spine treated between 1990 and 2008 were selected for review. This resulted in 178 cases of primary malignant, 335 benign lesions, 434 spinal metastases, and 162 myelomas. Out of 513 cases of primary bone tumors of the spine, 115 cases (20%) occurred in the cervical spine; 39 of these were primary malignant in origin (Table 57.1) and 76 were benign. Males were more frequently affected by malignancies than females (25:14); 43.5% of the cases occurred in patients

aged over 50 years; and 23% were in patients over 60 years of age. Fourteen cases arose from C2, four from C3, three from C4, four from C5, three from C6, and ten from C7. It is of some relevance to remark that in the series of 76 benign tumors (48 males and 28 females), 25 (33%) arose in the first two decades and 50% before the age of 30. Only two cases arose over the age of 50, one of which was over 60. Sixty metastases arose in the cervical spine out of 434 cases, and 26 cervical spine myelomas were noted out of 162 cases of patients with spinal involvement.

aged over 50 years; and 23% were in patients over 60 years of age. Fourteen cases arose from C2, four from C3, three from C4, four from C5, three from C6, and ten from C7. It is of some relevance to remark that in the series of 76 benign tumors (48 males and 28 females), 25 (33%) arose in the first two decades and 50% before the age of 30. Only two cases arose over the age of 50, one of which was over 60. Sixty metastases arose in the cervical spine out of 434 cases, and 26 cervical spine myelomas were noted out of 162 cases of patients with spinal involvement.

TABLE 57.1 Histologic Diagnoses of 39 Cases of Primary Malignant Tumors of the Cervical Spine Treated at C.A. Pizzardi and Rizzoli Institute, Bologna, Italy | ||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Most chordomas occurred at either C2 or C3. The osteosarcomas, malignant fibrous histiocytomas, and chondrosarcomas were located at the lower cervical segments. At initial presentation, multisegmental involvement was seen in six cases (chordoma, chondrosarcoma, and Ewing’s sarcoma). Although all malignant histologic types, except for chondrosarcomas, originated from the vertebral body, extension to include the whole vertebra was often the case at the time of diagnosis.

DIAGNOSIS

SIGNS AND SYMPTOMS

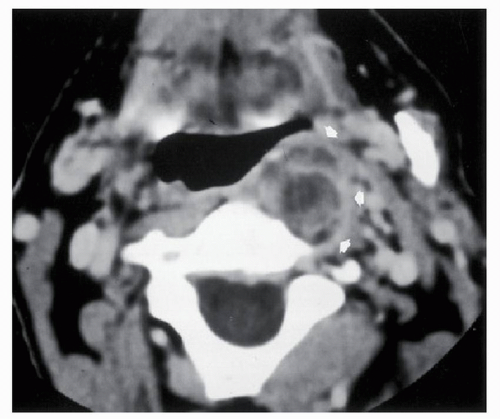

The clinical onset of primary tumors of the cervical spine is usually nonspecific (1,2). Persistent cervical pain, mostly night pain, and muscular spasm occur in most patients. Dysphagia (Fig. 57.1) is associated with large lesions arising from C2 that extend ventrally (e.g., chordoma, Ewing’s sarcoma, plasmacytoma) and was observed in 8 of 46 cases (17.4%) in our series.

Pathologic fracture is the result of neoplastic erosion of the cortex or the collapse of the vertebral body after massive destruction of the cancellous bone and substitution with neoplastic tissue. Before 1980, 10 of 12 cases (83%) of primary tumors of the cervical spine presented with symptoms related to a pathologic fracture. In more recent times, with a high index of suspicion, early detection of these tumors is possible with bone scan, CT, or MRI. Thus, the rate of pathologic fractures at the onset of symptoms in primary malignant bone tumors of the cervical spine has fallen (20.6%; 7 of 34 observed since 1980).

Major neurologic symptoms occurred in 15 patients (38.5%). Five chordomas and two Ewing’s sarcomas presented with signs of cord compression and slow development of incomplete quadriplegia; in eight other cases (plasmacytomas and osteosarcomas), root compression with mild cord involvement was present at baseline.

DIAGNOSTIC IMAGING STUDIES

In the past, primary tumors of the cervical spine were discovered only by standard radiographs when associated with significant bone loss. Today, although plain radiographs remain the first imaging study, bone scan, CT, and MRI help to make definitive identification in patients suspected of having a malignant process (3). Symptoms that should suggest performing further studies after a negative plain radiograph are dysphagia, persistent night pain, sudden occurrence of neurologic symptoms, and extremity pain, which may or may not fit a dermatomal distribution.

STANDARD RADIOGRAPHS

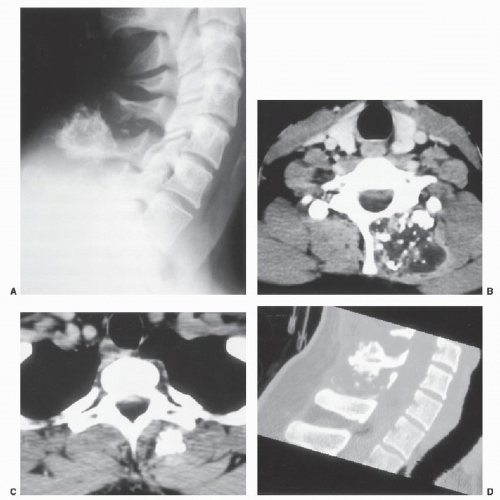

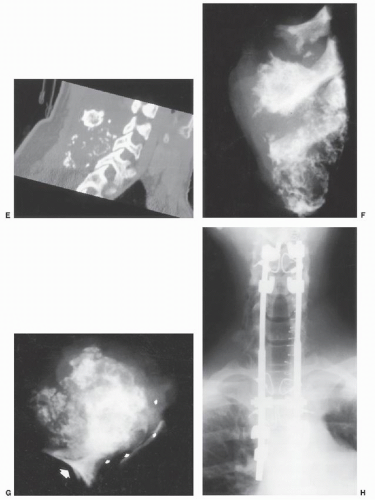

Due to the superposition of anatomical profiles typical of the standard radiographic picture of the cervical spine, the plain radiograph may be normal in some smaller lesions and in some myxoid tumors with expansion outside the vertebral body without evidence of bone involvement. Specific tumors have a more typical appearance; for example, chondrosarcomas are frequently calcified and lobulated (Fig. 57.2 and 57.2), and plasmacytomas and chordomas appear mostly as pure radiolucent lesions with variable definitions of their margins and are often difficult to distinguish from one another on plain radiographs. High-grade malignancy, such as an osteosarcoma, typically presents as an aggressive,

osteolytic destructive process accompanied by variable amounts of ossification. Round cell tumors (i.e., Ewing’s sarcoma and lymphomas) present with a typical permeative pattern and an associated soft tissue mass before there is evidence of bone destruction. The disks are involved only rarely but sometimes are surrounded by tumor. This factor is important in distinguishing tumors from pyogenic and tuberculous spinal infections.

osteolytic destructive process accompanied by variable amounts of ossification. Round cell tumors (i.e., Ewing’s sarcoma and lymphomas) present with a typical permeative pattern and an associated soft tissue mass before there is evidence of bone destruction. The disks are involved only rarely but sometimes are surrounded by tumor. This factor is important in distinguishing tumors from pyogenic and tuberculous spinal infections.

BONE SCAN

The technetium-99 (99Tc) scan in the workup of a malignant tumor is rarely necessary to find the lesion, which is almost always evident on standard radiographs. More frequently, the bone scan is used for detection of possible distant metastases. Only in cases of tumors like chordoma, which are difficult to see on plain radiographs due to the

infiltrative pattern of growth, are isotope scans helpful in guiding the use of a CT scan or MRI. Plasmacytomas are not always detectable by bone scan. Tomographic bone scan technology, however, can improve the sensitivity but not necessarily the specificity.

infiltrative pattern of growth, are isotope scans helpful in guiding the use of a CT scan or MRI. Plasmacytomas are not always detectable by bone scan. Tomographic bone scan technology, however, can improve the sensitivity but not necessarily the specificity.

COMPUTER-ASSISTED TOMOGRAPHY

The CT scan is highly sensitive for early bone destruction and in some clinicians’ minds remains unique for planning definitive surgical treatment. Contrast enhancement is often requisite to the careful evaluation of tumor margins and the tumor’s intrinsic vascularity. Preoperative CT imaging also provides an assessment of bony involvement and is important in the planning of both surgical resection and instrumented fixation.

MAGNETIC RESONANCE IMAGING

The MRI has greater sensitivity than the bone scan in detecting occult lesions not visualized on standard radiographs. The advantages are particularly evident for plasmacytomas. Furthermore, it is usually well tolerated, noninvasive, and safe. Compared with normal bone marrow, most tumors demonstrate decreased signal intensity on T1-weighted images and increased signal on T2-weighted sequences. Also, MRI is extremely sensitive to alterations in the vertebral body marrow, but it lacks specificity as to the etiology of the various pathologic processes. Any disorder or therapeutic procedure resulting in loss of myeloid elements—such as radiation therapy—may demonstrate increased signal intensity in the marrow secondary to fatty replacement of hematopoietic tissue. Soft tissue extension of a tumor and its particular relationship with the dura and nerve roots are better visualized by MRI than by CT scan (3).

MYELOGRAPHY

In most countries, myelography has now been replaced by MRI to assess spinal cord or nerve root compression, but still can be useful in concert with CT when a stainless steel device, which is known to cause metal artifacts, is present. CT myelography is also important in the diagnosis of spinal cord compression in patients who have a medical contraindication to MR imaging.

ANGIOGRAPHY

Angiography allows visualization of the vascularity of the tumor and the relationships of the tumor mass to the vertebral arteries. Preoperative embolization can be helpful in reducing intraoperative bleeding when an intralesional procedure is planned, but it can be performed only rarely because of common vascularity with the cervical cord and should be performed only in experienced institutions (14).

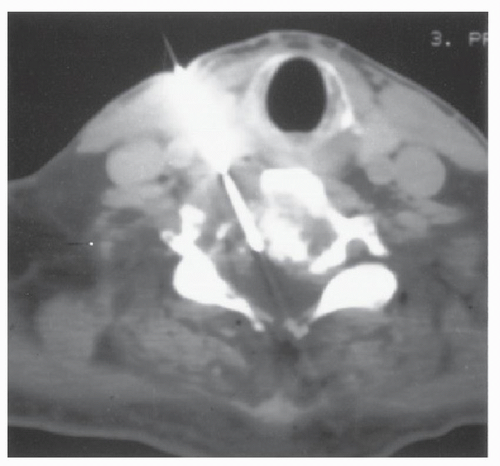

BIOPSY TECHNIQUES

Histologic confirmation of the diagnosis is mandatory to distinguish between primary and secondary malignancies and to differentiate malignancies that require varied treatments (e.g., chordoma vs. plasmacytoma) (1,5,15). Trocar/needle biopsy under CT scan guidance (Fig. 57.3) is theoretically a good way to achieve a diagnosis and usually does not require general anesthesia. Often CT scanning will help in reaching even the smallest of lesions. Correct use of this technique minimizes tumor contamination (16). The trocar/needle should be introduced at a point within the incision line, and the direction should pass through a muscle in order to resect the entire scar and needle track together with the tumor and ensure en bloc resection. Pressure should also be applied to reduce bleeding as the trocar is removed. In the cervical spine, this procedure is technically demanding and frequently is not well tolerated by patients. Knowing that these malignant primary tumors of the cervical spine are often extracompartmental at the time of discovery, it is generally not feasible to perform an en bloc resection. However, perioperative frozen sections should be examined before submitting the patient to an intralesional excision. The extent of surgical extirpation, together with the necessity of adjuvant therapies, will be decided by this important information obtained for histologic diagnosis. In rare cases of resectable tumors (small and often dorsally located), particular attention should be given to the imaging studies. In fact, the peculiar pattern of chondrosarcoma or chordoma must make the surgeon vigilant. In these cases, the risk of contamination by the myxoid tissue is extremely high, and at times justifies performing primary en bloc resection without previous histologic confirmation (Fig. 57.2).

STAGING

ONCOLOGIC STAGING

Oncologic and surgical staging is of the utmost importance in order to provide appropriate treatment. The

oncologic staging (5) is based on the histology and the local aggressiveness of the tumor, thereby defining its biologic behavior. The WBB (Weinstein, Boriani, Biagini) surgical staging system (5) describes the extension of the tumor and provides a tool for planning surgery, exchanging information, and evaluating the relationship between treatment and outcome. The Enneking staging system divides benign tumors into three stages and localized primary malignant tumors into four stages (IA-B and IIA-B). This system is based on clinical features, radiographic patterns, CT scan, MRI data, and histologic findings. It was formerly described for long bone tumors and later applied to spinal tumors (5). Histologically low-grade malignant tumors are included in stage I and are further subdivided into IA (the tumor remains inside the vertebra) and IB (the tumor invades perivertebral compartments). No capsule is found, but a thick pseudocapsule of reactive tissue is permeated by small microscopic islands of neoplastic tissue. High-grade malignancies are defined as IIA and IIB. The neoplastic growth is so rapid that the host has no time to form a continuous reactive tissue layer. These rapidly growing tumors are known to seed locally with satellite lesions or to have skip metastases at a distance from the main tumor mass. These malignancies are usually seen on plain radiographs as radiolucent and destructive processes and may be associated with a pathologic fracture. The CT scan and MRI define the transverse and longitudinal extent of tumor and may confirm the absence of a reactive tissue layer.

oncologic staging (5) is based on the histology and the local aggressiveness of the tumor, thereby defining its biologic behavior. The WBB (Weinstein, Boriani, Biagini) surgical staging system (5) describes the extension of the tumor and provides a tool for planning surgery, exchanging information, and evaluating the relationship between treatment and outcome. The Enneking staging system divides benign tumors into three stages and localized primary malignant tumors into four stages (IA-B and IIA-B). This system is based on clinical features, radiographic patterns, CT scan, MRI data, and histologic findings. It was formerly described for long bone tumors and later applied to spinal tumors (5). Histologically low-grade malignant tumors are included in stage I and are further subdivided into IA (the tumor remains inside the vertebra) and IB (the tumor invades perivertebral compartments). No capsule is found, but a thick pseudocapsule of reactive tissue is permeated by small microscopic islands of neoplastic tissue. High-grade malignancies are defined as IIA and IIB. The neoplastic growth is so rapid that the host has no time to form a continuous reactive tissue layer. These rapidly growing tumors are known to seed locally with satellite lesions or to have skip metastases at a distance from the main tumor mass. These malignancies are usually seen on plain radiographs as radiolucent and destructive processes and may be associated with a pathologic fracture. The CT scan and MRI define the transverse and longitudinal extent of tumor and may confirm the absence of a reactive tissue layer.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree