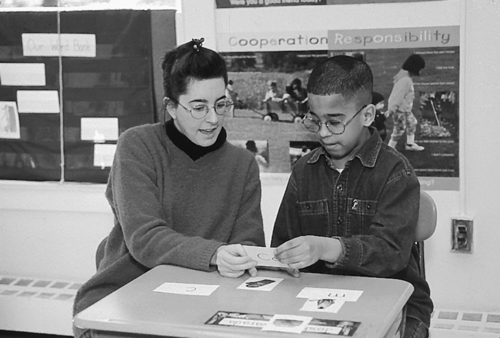

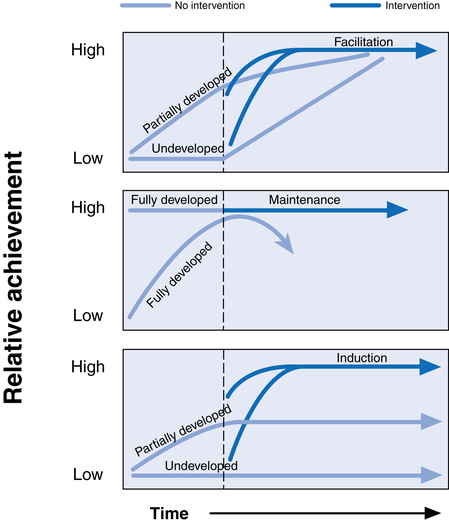

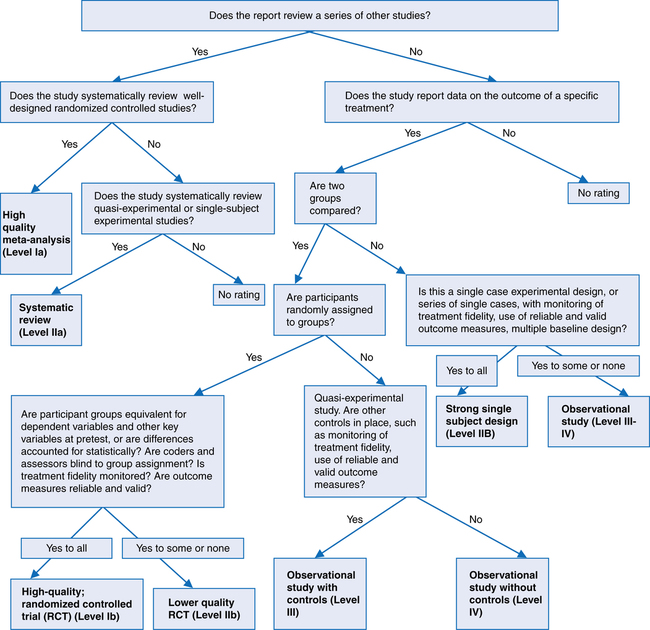

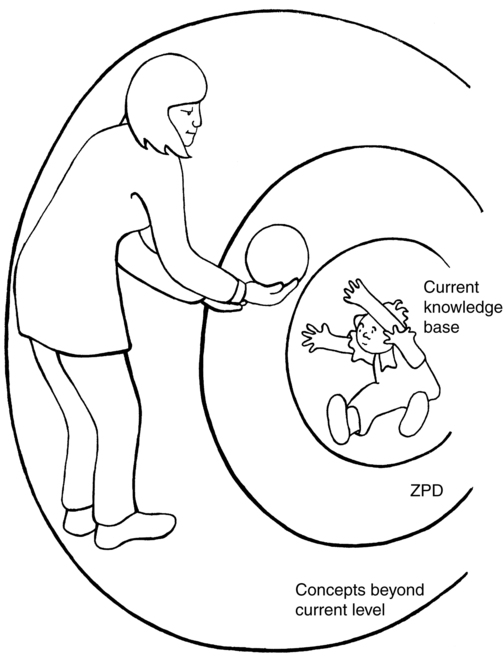

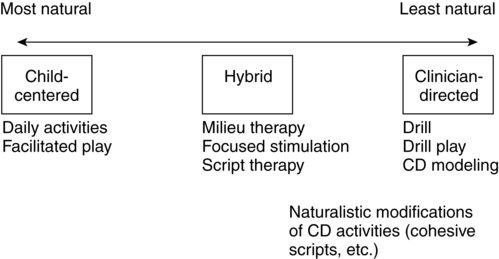

Chapter 3 Readers of this chapter will be able to do the following: 1. Discuss the various purposes of intervention. 2. List ways in which intervention can change communicative behavior. 3. Discuss way of identifying appropriate goals for communication intervention. 4. Describe interventions at various points on the continuum of naturalness. 5. List and discuss various contexts for providing intervention. 6. Describe methods of evaluating treatment outcomes. The first question we have to ask is, overall, what is the purpose of the intervention we are proposing? Olswang and Bain (1991) discussed three major purposes of intervention. The first is to change or eliminate the underlying problem, rendering the child a normal language learner, one who will not need any further intervention. Of course, all of us would like to achieve this with all our clients. Unfortunately, it is not usually possible. Frequently we do not even know what the underlying deficit is, let alone how to alleviate it. In a few instances, though, this might be a realistic goal. For a child with a hearing impairment, for example, if the loss is discovered during early childhood and amplification or cochlear implantation can be used to achieve normal or nearly normal hearing, the language pathologist might need only to provide the child with help in getting language skills to approximate the child’s developmental level (Geers, 2004; Niparko et al., 2010). Once these developmentally appropriate skills are achieved, normal acquisition could proceed, ideally anyway, without further intervention. Similarly, a young child who suffered a brain injury and developed an acquired aphasia might require intervention to restore language function, but a combination of intervention and the brain’s normal plasticity can sometimes result in language learning’s proceeding more or less normally, without need for further intervention after a period of time (Hanten et al., 2009). In the real world of language intervention, though, cases in which the underlying cause of the impairment is both known and fully remediable are the exception. Most children present with language disorders of unknown origin or associated with incurable conditions, such as intellectual disabilities or autism. In these more common cases, we must settle for something less than changing the child into a normal language learner. Olswang and Bain (1991) identified this second choice as changing the disorder. In this case we attempt to improve the child’s discrete aspects of language function by teaching specific behaviors. We teach the child, for instance, to expand the number of words and grammatical morphemes in sentences, to produce a broader range of semantic relations, or to use language more flexibly and appropriately. This makes the child a better communicator but does not guarantee that he or she will not need further help at a later time. This purpose is the one most commonly invoked when working with children who have developmental language disorders (DLD). A third option identified by Olswang and Bain is to teach compensatory strategies, not specific language behaviors. Rather than, for example, teaching a child with a word-finding problem to produce specific vocabulary items on command, we would attempt to teach the child how to use strategies to aid recall of vocabulary during conversational tasks. We might teach the child to use phonetic features of the target word, as a cue, or to try to think of words that rhyme with the word that the child can’t recall. This approach usually requires a good deal of cognitive maturity and is generally used to help older school-aged and adolescent students who have received language intervention for a number of years and will probably always retain some deficits (Wallach, 2005). Rather than trying to make their language normal, the clinician attempts to give them tools to function better with the deficits they have. According to Olswang and Bain (1991), when the purpose of intervention is to modify the disorder, language behavior can be changed in several ways. These alternatives are depicted in Figure 3-1. If all facilitation does is increase the rate of acquisition of a particular behavior without altering the child’s eventual language status, why bother to intervene? Gottlieb (1976) argued that facilitation could help a child increase his or her ability to differentiate among perceptions. In other words, facilitation can bring language to a higher level of awareness. This awareness can influence other aspects of development. For example, perhaps a child with a phonological disorder would outgrow his multiple articulation errors without intervention by age 8 or 9. But if intervention to overcome these errors is provided earlier, this intervention may not only improve articulation but also may focus the child’s attention on the sound structure of words. This increased awareness may contribute to the child’s phonological analysis skills, which, as we shall see later, are important for the development of literacy. Some writers (e.g., Whitehurst et al., 1991) suggest that if therapy is merely facilitative and the child would eventually outgrow the disorder anyway, there is no justification for intervening. But many clinicians (Olswang & Bain, 1991; Paul, 1991a; Robertson & Weismer, 1999) have argued that facilitative intervention is justified because of the other systems in development that accelerating language skills may affect. Take a child like Sammy. A second way that intervention can change behavior is through maintenance. Olswang and Bain (1991) explained that intervention for the purpose of maintenance preserves a behavior that would otherwise decrease or disappear. Gottlieb (1976) argued that maintaining behaviors is important to “keep an immature system intact, going, and functional so that it is able to reach its full development at a later stage” (p. 28). A toddler with a cleft palate, for example, for whom surgery was delayed for medical reasons, might need intervention to maintain babbling and early vocal behaviors. These behaviors would then be functioning and available for building intelligible language once the palatal vault was closed by surgery. Ochsner (2003) defined evidence-based practice as “the conscientious, explicit, and unbiased use of current best research results in making decisions about the care of individual clients” by integrating clinical expertise with the best available external clinical evidence from systematic research (Sackett et al., 2000). Dollaghan (2007) discussed these issues and reminded us that EBP does not only mean solving clinical problems by going to the external evidence, defined primarily as published literature, to find the best available scientific support for the use of specific intervention approaches, although it does mean that, too. Fey and Justice (2007) tell us that EBP includes evaluating internal evidence as well. Internal evidence comes from characteristics of the client and family, their willingness to participate in a treatment approach, and their preference; as well as our own clinician preferences, professional competencies, and values; and the values, policies, and culture of the institutions in which we work. Let’s talk about how we can evaluate external evidence first, then we’ll consider how internal evidence is included in this decision-making process. Dollaghan (2004, 2007) suggested we approach external evidence using three principles: 1. The opinions of expert authorities (including expert panels and consensus groups) should be viewed with skepticism. 2. All research is not created equal. Everything that gets published is not necessarily true (or to paraphrase your grandmother, you can’t believe everything you read). Some studies are better, and therefore better suited to inform clinical decisions, than others. 3. Clinicians must be critical about the quality of evidence they use to guide clinical decision-making. Dollaghan’s second and third principles tell us that not only must we view experts with skepticism, we must read published research with the same critical attitude. When we say “critical” in this context, though, we don’t just mean finding fault. We have a very specific set of criteria in mind that we want to measure the studies we read against. Fey and Justice (2007) outlined a series of questions we can ask ourselves to help determine the type and quality of a study. These are summarized in Figure 3-2. The answers to these questions allow us to classify a report we read in the literature according to the levels of evidence it provides. These levels are summarized in Table 3-1. The higher the level of evidence we can find for a particular approach, the more confident we can be that the approach has strong scientific support. Finn, Bothe, and Bramlett (2005) provide additional guidance for evaluating claims about evidence. Table 3-1 (Adapted from Fey, M., and Justice, L. [2007]. Evidence-based decision making in communication intervention. In R. Paul and P. Cascella [Eds.]. Introduction to clinical methods in communication disorders. Baltimore: Paul H. Brookes.) But suppose we find strong scientific support for a particular practice. Is that the end of our decision-making process? Perhaps, but perhaps not. I’ll give you an example. As we’ll see in Chapter 4, some of the strongest support available for any approach to eliciting initial speech from young children with autism spectrum disorders (ASD) is for behavioral, or operant, methods. These methods have been carefully investigated for many years, and have the greatest number of studies as well as the highest quality of research evidence behind them. Does this strong scientific evidence mean to us that every preverbal child with ASD must be given operant training? You’ve probably already thought of some reasons why the answer is “not necessarily.” Perhaps the clinician is not well trained or experienced in this approach, or perhaps it conflicts with her values. Maybe the parents don’t like it, and think it would make their child too passive. All these are examples of the internal evidence that also needs to go into deciding about an approach to intervention. What does EPB require of us, then? Do we have to read every published study in order to be EBP practitioners? Of course not—that would be impossible! Should we disregard scientific evidence if our own or a family’s values or experiences don’t match it? That would not be very responsible, either, since research does provide guidance in making clinical decisions. Fey and Justice (2007), Dollaghan (2007), and Sackett et al. (2000) outlined a reasonable approach to incorporating EBP that includes the following steps: 1. Formulate your clinical question, including the four “PICO” elements: I—Intervention being considered C—Comparison treatment (such as the prevailing approach or no treatment) Example: Would Brendan, a 3-year-old with ASD and no speech (P) show greater improvement with an intervention that targets speech through an operant approach (I), or one that uses an alternative modality, such as a Picture Exchange Communication System (PECS; Bondy & Frost, 1998) as shown by increases in verbal communicative acts (O)? 2. Use internal evidence (such as clinical experience and family preferences) to determine what your typical, “first stab” approach would be. Example: Brendan’s parents saw a newspaper article about PECS use in a nearby town. The child in the paper started saying a few words after working with PECS for several months. The parents think it makes sense and want to try it. You attended a PECS workshop several months ago, have used it with a few clients, and feel more confident using this technique than an operant approach with which you have little experience. You would opt for trying PECS first, other things being equal. 3. Find the external research evidence base. Use the American Speech-Language and Hearing Association (ASHA) database (www.asha.org) or other databases (such as MEDLINE or PsychInfo) available from libraries to search for information on your question. Start by reading the most recent review articles to find out what has been written lately; read abstracts of papers to decide if reading the whole paper will be worth your time. Choose just a few articles that come closest to answering your question to read in their entirety. If you have to choose just one or two, choose the most recent, since these will review earlier papers on the topic. 4. Grade the studies for (a) relevance to the clinical question, (b) the level of evidence provided by the study based on its design and quality, and (c) the direction, strength, and consistency of the observed outcomes, using the criteria in Table 3-1 and Figure 3-2. 5. Integrate internal and external evidence. Example: After reading several reviews and recent papers on behaviorist approaches, you are impressed with their high level of scientific support. You have read a few studies supporting PECS, but their quality is not very high. Still, the internal evidence for PECS seems strong, and Brendan has started doing more vocalizing, so he may be ready to use speech, once he learns some communication skills through PECS. 6. Evaluate the decision by documenting outcomes. Example: You take a baseline sample of play between Brendan and his mother for communicative acts using verbal and nonverbal means before starting PECS. Brendan is producing fewer than one communicative act/minute; most are vocal but not verbal. After 6 weeks of PECS, you take another sample of communication; Brendan now produces two acts/minute spontaneously, using both PECS and vocal behavior. He produces a one word approximation, with prompting from Mom: /mƏ/, for more, using it three times to request repetition of a tickle game. You conclude that PECS is doing its job, and decide to continue with the program, but to re-evaluate in another 6 weeks to be sure verbal communication continues to emerge. If it does not, you will consider a more direct speech approach, perhaps using more operant methods, at that time. As you can see from this brief introduction to EBP, it offers a framework to help us make the crucial clinical decisions that go into the planning of an intervention program. Brackenbury, Burroughs, & Hewitt (2008) provide additional guidelines for using EBP in clinical practice. Let’s look at some of the other elements that go into this planning process. McCauley and Fey (2006) and McLean (1989) suggested that there are three aspects of the intervention plan: the intended products, or objectives, of the intervention; the processes used to achieve these objectives; and the contexts, or environments, in which the intervention takes place. Let’s see what each of these aspects entails. A major source of information for goal setting is the assessment data. The appraisal tells us about the child’s current level of functioning in the various language areas. McCauley and Fey (2006) describe intervention goals at three levels. These include the following: Basic goals: Identify areas selected because of their importance for functionality or because of the severity of the deficit; these are general goals and usually correspond to long-term objectives in an educational plan (e.g., new grammatical forms). Intermediate goals: Provide greater specification within a basic goal; usually there are several levels of intermediate goals associated with each basic goal (e.g., auxiliaries, articles, pronouns). Specific goals: Specific instances of the language form, content, or use identified as intermediate goals. These are considered steps along the way to the broader and more functional basic goals, and should be based on the child’s functional readiness, those which the child uses correctly on occasion or for which the child produces obligatory contexts without producing the target form (e.g., is, are; a, the, he, she). Because many children with DLD have multiple linguistic deficits, it is helpful to have some criteria for setting priorities among the deficits identified in the baseline assessment. Nelson, Camarata, Welsh, Butkovsky, and Camarata (1996) found that both forms that did not appear in the child’s speech at all and forms that were used correctly some of the time were equally amenable to improvement with intervention. This research suggests that both these types of forms make suitable intervention targets. Fey (1986) and Fey, Long, and Finestack (2003) suggested, though, that forms that the child is already using a majority of the time correctly, even if some errors are still being made, should not be targeted for intervention. These forms are well on their way to mastery and will probably improve without direct teaching. Their suggestions are summarized in Box 3-1. This strategy for goal setting can be thought of as targeting the child’s zone of proximal development (Levykh, 2008; Schneider & Watkins, 1996; Shepard, 2005; Vygotsky, 1978). The zone of proximal development (ZPD) is the distance between a child’s current level of independent functioning and potential level of performance. In other words, the ZPD defines what the child is ready to learn with some help from a competent adult. Figure 3-3 gives a schematic representation of the ZPD. Choosing a goal within the child’s current knowledge base is wasting the child’s time, teaching something that is already known. Unfortunately, this error is sometimes made in intervention out of a misguided desire to ensure that the child succeeds on an intervention task. If a goal, such as production of a plural morpheme, is identified, and a child is found to perform at 80% correct on the first activity involving this morpheme, this indicates that the child does not need to be taught it. To persist in providing intervention on such an objective is to work short of the child’s ZPD. The client is not being challenged to assimilate new knowledge and is simply demonstrating what he or she has already learned. This may make the clinician feel good, but it does not help the child acquire new forms and functions of language. Similarly, it is important to choose objectives that are not beyond the client’s ZPD. If a goal is too far above the current knowledge base, the child will be unable to acquire it efficiently and may not learn it at all. For a child in the two-word stage of language production, for example, using comparative “-er” forms, which are normally acquired at a developmental level of 5 to 7 years (Carrow-Woolfolk, 1999a), is in most circumstances too far from the child’s current level of functioning to be an appropriate goal. Again, the probable range of the ZPD is based on detailed assessment data, which pinpoints where the child is already functioning, and on knowledge of normal development, which allows us to determine the next few pieces of language development to fall into place. Lidz and Gindis (2003) and Schneider and Watkins (1996) point out that using dynamic assessment techniques to establish the ZPD also is helpful. This would mean identifying a particular form that is used infrequently or not at all in the client’s spontaneous speech. Diagnostic teaching could be used to determine whether adult scaffolding makes it possible for the child to produce the form more accurately or often. If so, the form is within the child’s ZPD and makes an appropriate therapy target. Fey (1986), Lahey (1988), and McCauley and Fey (2006) all emphasized the importance of choosing objectives not only on developmental grounds, but also on the grounds of how efficient the targeted behaviors will be in increasing a child’s ability to communicate. This suggests that when a variety of communicative problems emerges from assessment, it makes sense to choose skills that most readily accomplish social goals as highest-priority targets for intervention. This dictum, articulated by Slobin (1973), tells us that when choosing targets for intervention, we must be careful to require that the child do only one new thing at a time. In targeting a new form, such as color vocabulary, we need to ask the child to use this form to serve a communicative function that has already been expressed with other forms. For example, if a child has used “big” and “little” to express attribution relations in two-word sentences, we could ask him or her to produce color words in these two-word attribution utterances. But if the child is not yet producing any utterances encoding the semantic relation of attribution, color vocabulary might not be a wise choice, or it ought to be taught in a simple labeling context using one-word utterances rather than two-word phrases. Another consideration in choosing intervention targets for young children in the first stages of language, when mean utterance lengths are less than three morphemes, was pointed out by Fey (1986) and Schwartz and Leonard (1982). This concerns the phonological abilities of the client. Schwartz and Leonard showed that young children are less likely to acquire the production (but not necessarily the comprehension) of new words if the new words contain phonological segments or syllable shapes that the children are not already producing in their other words. So “shoe” would not be a good word to choose as one of the vocabulary goals for a child who was not using any words containing the /∫/ sound, even though “shoe” might be a good choice from other perspectives. Similarly, plural morphemes might not be a high-priority goal for clients who did not produce any /s/ or /z/ sounds in their current vocabulary. For developmentally young children, phonological constraints can be quite powerful and should be factored into decisions about targets for language production. Fey (1986) also pointed out that the ease with which a form or function can be taught should be considered in choosing objectives for intervention. He suggested that forms that are more teachable are (1) easily demonstrated or pictured; (2) taught through stimulus materials that are easily accessed and organized; and (3) used frequently in naturally occurring, everyday activities in which the child is engaged. Fey (1986) discussed a continuum of naturalness in intervention approaches. This continuum represents the extent to which the settings and activities in intervention resemble “real life” or the world outside the clinic room (Figure 3-4). We can vary intervention activities along this continuum of naturalness. Activities in language intervention can be a lot like the activities a child engages in during the rest of his or her life, or they can be very different. We can go from very naturalistic settings and activities such as play in the child’s home to very contrived activities, such as drill in a setting such as a clinic room, or we can choose settings and activities somewhere midway along this continuum. Three basic approaches to intervention identified by Fey (1986) will be outlined here. We don’t mean to suggest that a clinician has to choose just one of them. Our aim should be to make the best match among a particular client, a particular objective, and an intervention approach. Some clients may do better with one approach than another. Other clients may do well with one approach for one objective and a different approach for another. One objective may be well suited to a highly structured approach; another may be better served by a more open-ended approach. Often, several activities are designed to address a particular objective—some highly structured, some with a low level of structure, and others a compromise between the two. The important thing is to be aware of the range of approaches available for planning intervention activities and to be able to take advantage of this range of approaches in setting up a comprehensive, economical, efficient intervention program that meets each client’s individual needs. We should also, as we will see later in the chapter, evaluate the available evidence in the research literature for the effectiveness of particular approaches with particular goals for particular kinds of clients. In these approaches, the clinician specifies materials to be used, how the client will use them, the type and frequency of reinforcement, the form of the responses to be accepted as correct, and the order of activities—in short, all aspects of the intervention. Clinician-directed (CD) approaches, also referred to as drill (Shriberg & Kwiatkowski, 1982a) or discrete trial intervention (DTI), attempt to make the relevant linguistic stimuli highly salient, to reduce or eliminate irrelevant stimuli, to provide clear reinforcement to increase the frequency of desired language behaviors, and to control the clinical environment so that intervention is optimally efficient in changing language behavior. CD approaches tend to be less naturalistic than other approaches we will discuss, since they involve so much control on the part of the clinician and since they purposely eliminate many of the natural contexts and contingencies of the use of language for communication. Peterson (2004) defined these approaches as ones in which the clinician selects the stimulus items, divides the target language skill into a series of steps, presents each step in a series of massed trials until the client meets a criterion level of performance, and then provides an arbitrary reinforcement. Roth and Worthington (2010) provide an excellent introduction to this approach. Their summary of this basic training protocol appears in Box 3-2. Proponents of this approach (e.g., Connell, 1987; Fey & Proctor-Williams, 2000; Smith, Eikeseth, Sallows, & Graupner, 2009) also point out that its unnaturalness is itself an advantage. They argue that if clients were going to learn language the “natural” way, by listening and interacting with others, they would not need intervention. The fact that the child has, for whatever reason, failed to learn language through natural interactions suggests that something else is needed. The something else, in this view, is the highly structured, clinician-controlled, tangibly reinforced context of the behaviorist’s intervention. There is something to be said for this position. CD approaches have been shown in a large literature of research studies to be consistently effective in eliciting a wide variety of new language forms from children with language disabilities of many types (see Abbeduto & Boudreau, 2004; Fey, 1986; Goldstein, 2002; Paul & Sutherland, 2005; Peterson, 2004; Reichow & Wolery, 2009; Rogers, 2006, for reviews). The proponents of the CD approach appear to be justified in arguing that children who have not learned language the “old-fashioned way,” by interacting naturally with their parents, benefit from formal behavior modification procedures. Furthermore, some research (Friedman & Friedman, 1980) suggests that, while children with higher IQs learn better in a more interactive intervention program, those with lower IQs or more severe disabilities perform better when a CD approach is used. Connell (1987) showed, using an invented morpheme, that children with normal language acquisition learned more efficiently when the form was merely modeled for them, whereas children with DLD learned the form better when they were required to imitate the instructor’s production of it. These studies tend to support the behaviorist position that CD approaches to language intervention work better than more naturalistic ones for children with DLD. Studies of children with ASD have also shown that CD approaches appear superior to more eclectic approaches for improving language and cognitive skills (e.g., Cohen, Amerine-Dickens, & Smith, 2006; Eikeseth, Smith, Jahr, & Eldevik, 2002; Eikeseth, Smith, Jahr, & Eldevik, 2007). But, of course, that’s not the whole story. Cole and Dale (1986), for example, were not able to replicate the Friedman and Friedman results and found no differences between interactive and CD approaches. Nelson et al. (1996) showed more rapid acquisition of grammatical targets and increased generalization with a conversational intervention treatment than an imitative one. Camarata, Nelson, and Camarata (1994) reported that children with language impairments learned syntactic targets more quickly under naturalistic conditions than with a CD approach. A meta-analysis by Delprato (2001) suggested that naturalistic interventions showed a consistent advantage over CD methods. Howlin, Magiati, Charman, and MacLean (2009) found CD approaches worked well for some children but not others. More fundamentally, perhaps, numerous studies (e.g., Hughes & Carpenter, 1983; Mulac & Tomlinson, 1977; Zwitman & Sonderman, 1979; see Peterson, 2004, for review) show difficulties in generalization to natural contexts of forms taught with a CD approach, even when use reaches high levels of accuracy within the CD framework. Cirrin and Gillam (2008) report, in a review of literature, that imitation (CD), modeling (child-centered, CC), or modeling plus evoked production (hybrid) all are equally but modestly effective in teaching new syntactic and morphological forms. Gillum et al. (2003), while generally favoring more naturalistic approaches, argue that clinicians and researchers need to determine which developmental profiles in clients are best matched to particular intervention methods. It seems, then, that while CD approaches can be highly efficient in getting children to produce new language forms, they are not so effective in getting them to incorporate these forms into real communication outside the structured clinic setting, and that more naturalistic methods can also provide an efficient means of addressing language targets. What shall we make of these findings? Some writers, including Hubbell (1981), Norris and Hoffman (1993), and Owens (2009), have argued that the lack of generalization seen in CD approaches renders them useless and that the only approaches that are right for language intervention are more natural and interactive. This view, in our opinion, involves “throwing the baby out with the bath water.” Since CD approaches have proven efficacy in eliciting new language forms, why not take advantage of this efficacy? CD approaches can be used in initial phases of treatment to elicit forms that the child is not using very much spontaneously or at all. Fey, Long, and Finestack (2003) argue that drill formats that emphasize contrasts between two forms (such as past/present or singular/plural) are the most effective use of CD formats. Either simultaneously, or later, once the form or function has been stabilized with a CD approach, some of the more naturalistic approaches we will discuss can be used to help bring the form into the child’s conversational repertoire (Smith, 2001). Let’s look at three major varieties of CD activities: drill, drill play, and modeling. Shriberg and Kwiatkowski (1982a) defined several types of clinical activities in terms of their degree of structure. The most highly structured in their framework is drill, which makes use of the classic DTI format. In a drill activity, the clinician instructs the client concerning what response is expected and provides a training stimulus, such as a word or phrase to be repeated. These training stimuli are carefully planned and controlled by the clinician. Often they contain prompts or instructional stimuli that tell the child how to respond correctly, for example by imitating the clinician. If prompts are used, they are gradually eliminated or faded on a schedule predetermined by the clinician. When prompts are used, the client provides a response to the clinician’s stimulus. If this response is the one the clinician intended, the child is reinforced with verbal praise or some tangible reinforcer, such as food or a token. A motivating event also may be provided. For example, if the child is to label clothing items, he or she may be asked to place a sticker of the item in a sticker album after it has been named appropriately and the response has been reinforced. If the client’s response is not the intended target, the clinician attempts to shape the response by reinforcing the production of parts of the complete target and gradually increasing the number of components that must appear correctly to obtain the reinforcement. Drill is the most efficient intervention approach in that it provides the highest rate of stimulus presentations and client responses per unit time. Shriberg and Kwiatkowski (1982a) found drill and drill play to be equally efficient and effective in eliciting responses in phonological intervention. Furthermore, clinicians in the study liked drill play a lot better than they did drill and believed that their clients did, too. Do these findings about phonological intervention transfer to language? We don’t really know, since this question has not been addressed in language intervention research in as clear a manner as Shriberg and Kwiatkowski have addressed it. But it seems reasonable to expect the two modes of intervention to produce similar outcomes with semantic, syntactic, pragmatic, and phonological goals. These findings suggest that many of the advantages of highly structured CD approaches can be retained while client motivation and clinician comfort are increased, by small but well-thought-out modifications of the basic DTI approach. Fey (1986) presented a second CD alternative to straight drill procedures. This arises from social learning theory and involves the use of a third-person model—thus the name, modeling approach. Like drill, modeling uses a highly structured format, extrinsic reinforcement, and a formal interactive context. But here, instead of imitating, the child’s job is to listen. The client listens as the model provides numerous examples of the structure being taught. Through listening, the child is expected to induce and later produce the target structure. The child never has to imitate a structure immediately after the model. Instead this procedure implicitly requires the child to find a pattern in the model’s talk that is similar across all the stimuli presented. In Leonard’s (1975a) modeling procedure, a “confederate,” such as a parent, is used by the clinician as a model. The clinician, after pretesting the client on the target structure, gives the model a set of pictures not used in the pretest and asks, “What’s happening here?” The confederate provides, for example, a be + (verb)+-ing utterance that describes each picture presented by the clinician (e.g., “the boy is drinking,” “the girl is eating,” “the cat is walking”). After 10 or 20 of these descriptions, the client is asked to “talk like” the model and to describe a similar but not identical set of pictures. In this phase the model and client alternate their productions until the child produces three consecutive correct versions. Then, the child is asked to continue until a criterion (say, 8 out of 10 consecutive correct responses) is reached. At this point, the client would be tested on the pretest stimuli without models. This method can easily be adapted when a confederate is not available by using a doll or puppet (with the clinician’s voice) as a model. For another kind of client, too, the CD approach may not be the best first step. This is the child that Fey (1986) called “unassertive.” An unassertive child responds to speech, but rarely initiates communication. These children are passive communicators who let others control interactions. In a sense, a CD approach panders to these clients’ propensity to sit back and let others do the interactive work. Having these clients respond when and how they are told to is essentially reinforcing them to continue the old, passive communication pattern. For both these children—the obstinate child and the unassertive communicator—CD approaches may not be the most appropriate first step in an intervention program. That is not to say that CD approaches never work for these clients, only that we may need to do something else first before we ask them to work with us. For the obstinate and unassertive child particularly, the child-centered (CC) approach (Fey, 1986; Girolametto & Weitzman, 2006; Sheldon & Rush, 2001) may be a good introduction to intervention. CC approaches can be appropriate adjuncts to the program for many children with language disorders. CC approaches go by several names, including indirect language stimulation (ILS; Fey, 1986), facilitative play (Hubbell, 1981), pragmaticism (Arwood, 1983), and developmental or developmental/pragmatic approaches (Prizant & Wetherby, 2005a). In using a CC approach, a clinician arranges an activity so that opportunities for the client to provide target responses occur as a natural part of play and interaction. From the child’s point of view, the activity is “just” play or conversation. A clinician may use a variety of linguistic models as instructional language when they seem appropriate in the context of the child’s activity. There are no tangible reinforcers, no requirements that the child provide a response to the clinician’s language, and no prompts or shaping of incorrect responses when they do occur, although the clinician does consequate, or follow up, any child remarks in specific ways, as we’ll see.

Principles of intervention

The purpose of intervention

How can intervention change language behavior?

Facilitation

Maintenance

Developing intervention plans

Evidence-based practice

Level

Type(s) of Evidence

Ia

A systematic meta-analysis of multiple well-designed randomized controlled studies.

Ib

A well-conducted single randomized controlled trail (RCT) with a narrow confidence interval

IIa

A systematic review of nonrandomized quasi-experimental trials or a systematic review of single subject experiments that documents consistent study outcomes.

IIb

A high quality quasi-experimental trial or a lower quality RCT or a single subject experiment with consistent outcomes across replications.

III

Observational studies with control (retrospective studies, interrupted time-series studies, case-control studies, cohort studies with controls)

IV

Observational studies without controls

V

Expert opinions without critical appraisal or theoretical background or basic research

Products of intervention: setting goals

Communicative effectiveness

New forms express old functions; new functions are expressed by old forms

Client phonological abilities

Teachability

Processes of intervention

Intervention approaches

The clinician-directed approach

Drill

Drill play

Modeling

Child-centered approaches

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Justin was born with severe cerebral palsy. After years of intervention he was still not able to produce much intelligible speech. In middle school, his language comprehension and literacy skills were near age level, though. He had been given an augmentative communication device that could speak what he typed out with a headstick. But his parents commonly forgot to bring the device along when they went out, and often forgot to send it to school with him, so he was forced to revert to vocal attempts to communicate, which were usually not very successful. Without an easy way to communicate with him, his classmates usually left him alone with his aide, so he had few peer interactions. His teacher interacted mostly with the aide, rather than Justin, giving her assignments to have Justin complete. His parents requested additional therapy for the oral language since they felt he was trying so hard to communicate that way. Instead, his clinician helped the family obtain a speech-generating program that worked on a smartphone. She also helped Justin devise a signal to use as a request for the phone, in order to remind his parents to send it to school with him. In addition, the clinician showed Justin’s classmates how to use the program, so that they could talk to Justin by using it, as well as allowing him to talk to them. The classmates thought that being able to bring his phone to class was pretty cool and started spending more time interacting with Justin. The clinician encouraged the teacher, too, to use the device to give Justin his assignments directly, rather than talking to the aide. Now Justin can usually get someone to talk with him when he wants to say something. He also spends more time interacting with peers and participating, through his device, in class discussions.

Justin was born with severe cerebral palsy. After years of intervention he was still not able to produce much intelligible speech. In middle school, his language comprehension and literacy skills were near age level, though. He had been given an augmentative communication device that could speak what he typed out with a headstick. But his parents commonly forgot to bring the device along when they went out, and often forgot to send it to school with him, so he was forced to revert to vocal attempts to communicate, which were usually not very successful. Without an easy way to communicate with him, his classmates usually left him alone with his aide, so he had few peer interactions. His teacher interacted mostly with the aide, rather than Justin, giving her assignments to have Justin complete. His parents requested additional therapy for the oral language since they felt he was trying so hard to communicate that way. Instead, his clinician helped the family obtain a speech-generating program that worked on a smartphone. She also helped Justin devise a signal to use as a request for the phone, in order to remind his parents to send it to school with him. In addition, the clinician showed Justin’s classmates how to use the program, so that they could talk to Justin by using it, as well as allowing him to talk to them. The classmates thought that being able to bring his phone to class was pretty cool and started spending more time interacting with Justin. The clinician encouraged the teacher, too, to use the device to give Justin his assignments directly, rather than talking to the aide. Now Justin can usually get someone to talk with him when he wants to say something. He also spends more time interacting with peers and participating, through his device, in class discussions. Sammy is a cute, apparently bright 3-year-old who has trouble communicating. His speech is hard to understand, his sentences are limited to two or three words, and he tends to push first and talk later. An appraisal by the local education agency (LEA) revealed that his problems were pretty much limited to expressive language; his cognitive and receptive language skills were at age level. He was having some difficulty with social skills and was showing some behavior problems, though, and seemed to be very frustrated about not getting his ideas across. His parents were quite anxious and concerned, particularly about his difficulties in getting along with other children. The LEA reported that he did not qualify for intervention because his deficits were limited to expression and were in the mild-to-moderate range. His parents were told that he would probably outgrow these deficiencies by the time he got to school. But they didn’t want to wait. They were able to arrange for him to see a clinician through a private charitable agency. After 6 months his intelligibility, although still not normal for a child nearly 4 years old, had improved so that at least half of his utterances were comprehensible to peers. Sammy seemed a happier little boy; his aggressive behavior had decreased, neighbors were inviting him over to play more often, and his parents were feeling much more at ease.

Sammy is a cute, apparently bright 3-year-old who has trouble communicating. His speech is hard to understand, his sentences are limited to two or three words, and he tends to push first and talk later. An appraisal by the local education agency (LEA) revealed that his problems were pretty much limited to expressive language; his cognitive and receptive language skills were at age level. He was having some difficulty with social skills and was showing some behavior problems, though, and seemed to be very frustrated about not getting his ideas across. His parents were quite anxious and concerned, particularly about his difficulties in getting along with other children. The LEA reported that he did not qualify for intervention because his deficits were limited to expression and were in the mild-to-moderate range. His parents were told that he would probably outgrow these deficiencies by the time he got to school. But they didn’t want to wait. They were able to arrange for him to see a clinician through a private charitable agency. After 6 months his intelligibility, although still not normal for a child nearly 4 years old, had improved so that at least half of his utterances were comprehensible to peers. Sammy seemed a happier little boy; his aggressive behavior had decreased, neighbors were inviting him over to play more often, and his parents were feeling much more at ease.