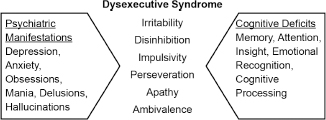

13 PSYCHIATRIC ISSUES IN HUNTINGTON’S DISEASE Figure 13.1

INTRODUCTION

Huntington’s disease (HD) is a neuropsychiatric disorder characterized by impairments in movement, emotional regulation, and cognitive functioning.

Huntington’s disease (HD) is a neuropsychiatric disorder characterized by impairments in movement, emotional regulation, and cognitive functioning.

Psychiatric disorders are a frequently encountered and longitudinal problem in HD.1,2

Psychiatric disorders are a frequently encountered and longitudinal problem in HD.1,2

The psychiatric and cognitive symptoms may often be more challenging to manage than the movement disorder itself and lead to a greater decline in quality of life for both patients and caregivers.3

The psychiatric and cognitive symptoms may often be more challenging to manage than the movement disorder itself and lead to a greater decline in quality of life for both patients and caregivers.3

The average age at the onset of HD is typically identified as 40 years; however, this refers to the emergence of physical deficits (ie, chorea). In many patients with HD, the psychiatric and cognitive deficits present much earlier.

The average age at the onset of HD is typically identified as 40 years; however, this refers to the emergence of physical deficits (ie, chorea). In many patients with HD, the psychiatric and cognitive deficits present much earlier.

There are complicated family dynamics that are important to consider in evaluating the psychiatric vulnerability of any patient with HD.

There are complicated family dynamics that are important to consider in evaluating the psychiatric vulnerability of any patient with HD.

Dysexecutive syndrome in HD is a complex group of behaviors resulting from the manifestation of psychiatric and cognitive deficits (Figure 13.1).

Dysexecutive syndrome in HD is a complex group of behaviors resulting from the manifestation of psychiatric and cognitive deficits (Figure 13.1).

GENETIC TESTING

Genetic counseling is a critical component of the genetic testing process.

Genetic counseling is a critical component of the genetic testing process.

All patients should ideally be seen by a mental health provider before testing, to be evaluated for their emotional and cognitive capacity to receive and understand the results of genetic testing.

All patients should ideally be seen by a mental health provider before testing, to be evaluated for their emotional and cognitive capacity to receive and understand the results of genetic testing.

Predictive testing for minors is not routinely recommended.

Predictive testing for minors is not routinely recommended.

Common acute emotional reactions associated with a positive test result include sadness, anger, anxiety, agitation, shock, tearfulness, and hopelessness.

Common acute emotional reactions associated with a positive test result include sadness, anger, anxiety, agitation, shock, tearfulness, and hopelessness.

Psychiatric and cognitive deficits in Huntington’s disease leading to dysexecutive syndrome.

Family dynamics may become altered by a positive or negative test result. For example, parents may feel guilt about passing the gene on to their offspring, children with a positive gene may display anger toward the parent or an unaffected sibling, and unaffected individuals may experience relief and gratitude about not passing the gene on to subsequent generations.

Family dynamics may become altered by a positive or negative test result. For example, parents may feel guilt about passing the gene on to their offspring, children with a positive gene may display anger toward the parent or an unaffected sibling, and unaffected individuals may experience relief and gratitude about not passing the gene on to subsequent generations.

COGNITIVE DYSFUNCTION

Cognitive deficits usually begin in a gradual fashion, initially affecting the speed of cognitive processing and compromising executive functions, such as organization, planning, attention, and multitasking. Visuospatial dysfunction, decline in working memory, and learning impairments are other frequently seen cognitive deficits.4

Cognitive deficits usually begin in a gradual fashion, initially affecting the speed of cognitive processing and compromising executive functions, such as organization, planning, attention, and multitasking. Visuospatial dysfunction, decline in working memory, and learning impairments are other frequently seen cognitive deficits.4

Inattention and distractibility can be accentuated by motor abnormalities, such as restlessness and chorea.

Inattention and distractibility can be accentuated by motor abnormalities, such as restlessness and chorea.

Cortical impairments, such as aphasia, amnesia, and agnosia, are rarely seen in HD. Language comprehension also remains fairly unaffected.

Cortical impairments, such as aphasia, amnesia, and agnosia, are rarely seen in HD. Language comprehension also remains fairly unaffected.

Cognitive inflexibility, inability to appreciate negative consequences, lack of self-awareness, and failure to read social cues and facial expressions are other features that may be encountered in HD and contribute to abnormal behavioral reactions.5

Cognitive inflexibility, inability to appreciate negative consequences, lack of self-awareness, and failure to read social cues and facial expressions are other features that may be encountered in HD and contribute to abnormal behavioral reactions.5

Cognitive dysfunction may be the consequence of or exacerbated by overlapping psychiatric symptoms, such as depression and anxiety, or it may be the result of treatment-related adverse effects (ie, sedation).

Cognitive dysfunction may be the consequence of or exacerbated by overlapping psychiatric symptoms, such as depression and anxiety, or it may be the result of treatment-related adverse effects (ie, sedation).

The Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MOCA) is a useful screening instrument in detecting HD-related cognitive changes. Deficits in the serial 7s exercise of the Mini-Mental Status Examination (MMSE) are another change seen in early HD.

The Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MOCA) is a useful screening instrument in detecting HD-related cognitive changes. Deficits in the serial 7s exercise of the Mini-Mental Status Examination (MMSE) are another change seen in early HD.

Treatment of Cognitive Dysfunction

There are no significant pharmacologic interventions to change the course of cognitive decline.

There are no significant pharmacologic interventions to change the course of cognitive decline.

Efforts should be directed at reducing any medications that may be contributory while incorporating interventions that center around environmental adjustments, such as these:

Efforts should be directed at reducing any medications that may be contributory while incorporating interventions that center around environmental adjustments, such as these:

Minimizing distractions

Minimizing distractions

Implementing routines and structure

Implementing routines and structure

Creating reminder lists

Creating reminder lists

Allowing extended time to complete tasks

Allowing extended time to complete tasks

DEPRESSION AND APATHY

The estimated lifetime prevalence of depression in HD is 30% to 70%.3

The estimated lifetime prevalence of depression in HD is 30% to 70%.3

Patients are susceptible to depression at any point in the course of HD, even if the symptoms are relatively mild and cause minimal functional impairment. As in other degenerative conditions, hopelessness may also surface after a significant change in quality of life (ie, loss of job, loss of driving privileges, increased falls).

Patients are susceptible to depression at any point in the course of HD, even if the symptoms are relatively mild and cause minimal functional impairment. As in other degenerative conditions, hopelessness may also surface after a significant change in quality of life (ie, loss of job, loss of driving privileges, increased falls).

Tetrabenazine, an approved treatment for chorea in HD, carries a boxed warning regarding its propensity to cause depression and suicidal thinking.

Tetrabenazine, an approved treatment for chorea in HD, carries a boxed warning regarding its propensity to cause depression and suicidal thinking.

Suicide rates are significantly higher in patients with HD than in the general population;6 therefore, acute changes in mood and/or an increase in hopelessness should be taken seriously, trigger an immediate assessment, and never be considered a normal reaction.

Suicide rates are significantly higher in patients with HD than in the general population;6 therefore, acute changes in mood and/or an increase in hopelessness should be taken seriously, trigger an immediate assessment, and never be considered a normal reaction.

Physicians should be aware of how many at-risk children a patient may have and be watchful for changes in mood if these children elect to undergo genetic testing. A positive test result may trigger guilt, self-directed anger, and/or thoughts of self-harm in the affected parent.

Physicians should be aware of how many at-risk children a patient may have and be watchful for changes in mood if these children elect to undergo genetic testing. A positive test result may trigger guilt, self-directed anger, and/or thoughts of self-harm in the affected parent.

Apathy, defined as a loss of motivation or initiation, appears to worsen with disease progression. Apathy is typically associated with a neutral mood, although it can occur in a patient with depression, which will accentuate the loss of motivation and lack of spontaneity.

Apathy, defined as a loss of motivation or initiation, appears to worsen with disease progression. Apathy is typically associated with a neutral mood, although it can occur in a patient with depression, which will accentuate the loss of motivation and lack of spontaneity.

Depression may be difficult to detect or evaluate later in the disease process because of the presence of apathy and impairments in speech and/or cognition. Severe depression may be complicated by hallucinations and delusions.

Depression may be difficult to detect or evaluate later in the disease process because of the presence of apathy and impairments in speech and/or cognition. Severe depression may be complicated by hallucinations and delusions.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree