14

PSYCHIATRIC ISSUES IN TOURETTE SYNDROME

INTRODUCTION

Tourette syndrome (TS) is considered to be a neuropsychiatric illness. Studies have shown that up to 88% of individuals display psychiatric comorbidity or psychopathology.1 Up to 36% have more than one psychiatric comorbidity.2

Tourette syndrome (TS) is considered to be a neuropsychiatric illness. Studies have shown that up to 88% of individuals display psychiatric comorbidity or psychopathology.1 Up to 36% have more than one psychiatric comorbidity.2

The presence of a psychiatric comorbidity correlates with a worse prognosis, exposure to more medications, and a greater degree of functional impairment.

The presence of a psychiatric comorbidity correlates with a worse prognosis, exposure to more medications, and a greater degree of functional impairment.

The age of onset of motor or phonic tics coincides with the onset of the most common psychiatric comorbidities, such as obsessive–compulsive disorder (OCD) and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD).

The age of onset of motor or phonic tics coincides with the onset of the most common psychiatric comorbidities, such as obsessive–compulsive disorder (OCD) and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD).

It is commonly thought that these psychiatric illnesses share neural circuitry with tic disorders

It is commonly thought that these psychiatric illnesses share neural circuitry with tic disorders

The severity of the symptoms associated with tics can be influenced by environmental changes or stresses.

The severity of the symptoms associated with tics can be influenced by environmental changes or stresses.

Effectively managing a tic disorder includes understanding the psychiatric/psychological aspects that are commonly seen with this illness.

Effectively managing a tic disorder includes understanding the psychiatric/psychological aspects that are commonly seen with this illness.

TICS AND BEHAVIOR

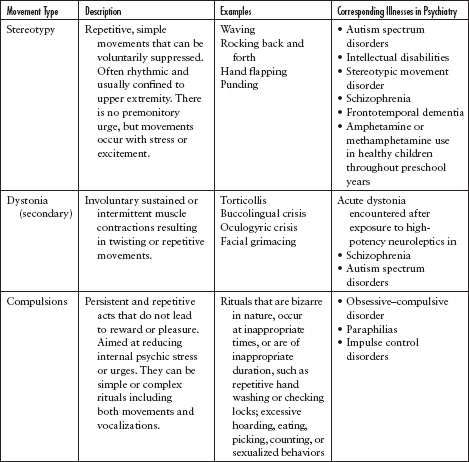

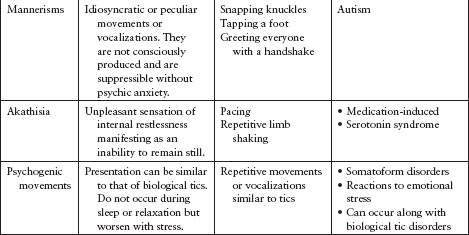

Tics themselves are categorized as either motor or vocal manifestations. Their characteristics include fluctuating symptomatology over time, suppressibility followed by rebound, suggestibility, and they are preceded by premonitory sensations. Multiple psychiatric symptoms can present in a similar manner (Table 14.1).

Tics themselves are categorized as either motor or vocal manifestations. Their characteristics include fluctuating symptomatology over time, suppressibility followed by rebound, suggestibility, and they are preceded by premonitory sensations. Multiple psychiatric symptoms can present in a similar manner (Table 14.1).

Persons with tic disorders may display behavioral symptoms even without psychiatric comorbidities, such as hyperarousal states manifesting as anxiety, hyperactivity, and even self-injurious behaviors.

Persons with tic disorders may display behavioral symptoms even without psychiatric comorbidities, such as hyperarousal states manifesting as anxiety, hyperactivity, and even self-injurious behaviors.

PSYCHIATRIC COMORBIDITIES

Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder

ADHD is a neurobehavioral disorder that affects 3% to 9% of children. It is characterized by symptoms of hyperactivity, impulsivity, and inattention.

ADHD is a neurobehavioral disorder that affects 3% to 9% of children. It is characterized by symptoms of hyperactivity, impulsivity, and inattention.

Children can exhibit symptoms of either inattention or hyperactivity, or they can meet the criteria for both. Symptoms must be present before the age of 11 years4 and must affect the individual in multiple settings (home, school, work, day care).

Children can exhibit symptoms of either inattention or hyperactivity, or they can meet the criteria for both. Symptoms must be present before the age of 11 years4 and must affect the individual in multiple settings (home, school, work, day care).

The frequency of ADHD in clinic samples of children with tic disorders is estimated at 50% to 70%.1 Conversely, up to 20% of children with ADHD present with a comorbid tic disorder.

The frequency of ADHD in clinic samples of children with tic disorders is estimated at 50% to 70%.1 Conversely, up to 20% of children with ADHD present with a comorbid tic disorder.

Studies suggest that the combination of a tic disorder plus ADHD results in greater overall impairment than either a tic disorder or ADHD alone.

Studies suggest that the combination of a tic disorder plus ADHD results in greater overall impairment than either a tic disorder or ADHD alone.

A comprehensive treatment program for a patient with a tic disorder and comorbid ADHD should include cognitive behavioral therapy plus psycho-educational and psychosocial interventions, along with a consideration of medications.

A comprehensive treatment program for a patient with a tic disorder and comorbid ADHD should include cognitive behavioral therapy plus psycho-educational and psychosocial interventions, along with a consideration of medications.

There is strong evidence to support the use of habit reversal training in individuals with TS and comorbid ADHD, and such training should be considered before and along with medication management.

There is strong evidence to support the use of habit reversal training in individuals with TS and comorbid ADHD, and such training should be considered before and along with medication management.

TREATMENT OF ATTENTION-DEFICIT/HYPERACTIVITY DISORDER

Stimulants (methylphenidate, dexmethylphenidate, dextroamphetamine, lisdexamfetamine, and mixed amphetamine salts) are widely recognized as first-line pharmacologic treatments of ADHD.

Stimulants (methylphenidate, dexmethylphenidate, dextroamphetamine, lisdexamfetamine, and mixed amphetamine salts) are widely recognized as first-line pharmacologic treatments of ADHD.

Multiple studies comparing the efficacy of stimulants have shown few differences between methylphenidate and mixed amphetamine salt preparations.

Multiple studies comparing the efficacy of stimulants have shown few differences between methylphenidate and mixed amphetamine salt preparations.

Available evidence indicates that 70% of children with ADHD will show a positive response to a stimulant trial and that approximately half of the nonresponders will show a positive response to a trial of an alternative stimulant.

Available evidence indicates that 70% of children with ADHD will show a positive response to a stimulant trial and that approximately half of the nonresponders will show a positive response to a trial of an alternative stimulant.

Stimulants, alpha-2-adrenoceptor agonists, atomoxetine, and partial dopamine agonists have been studied in individuals with comorbid tic disorders and ADHD. Stimulants may produce a transient worsening of tics upon initiation of the medication.

Stimulants, alpha-2-adrenoceptor agonists, atomoxetine, and partial dopamine agonists have been studied in individuals with comorbid tic disorders and ADHD. Stimulants may produce a transient worsening of tics upon initiation of the medication.

However, recent well-designed, controlled clinical trials have not indicated chronic exacerbation of tics in persons treated with stimulants.5,6

However, recent well-designed, controlled clinical trials have not indicated chronic exacerbation of tics in persons treated with stimulants.5,6

Alpha-2-adrenoceptor agonists activate presynaptic autoreceptors in the locus ceruleus and reduce norepinephrine release and turnover. These medications have been shown to be beneficial in reducing tics as well as hyper-activity and impulsivity in individuals with ADHD.

Alpha-2-adrenoceptor agonists activate presynaptic autoreceptors in the locus ceruleus and reduce norepinephrine release and turnover. These medications have been shown to be beneficial in reducing tics as well as hyper-activity and impulsivity in individuals with ADHD.

In a randomized, controlled study comparing clonidine, methylphenidate, and placebo, clonidine appeared to be most helpful for impulsivity and hyperactivity and methylphenidate for inattention.

In a randomized, controlled study comparing clonidine, methylphenidate, and placebo, clonidine appeared to be most helpful for impulsivity and hyperactivity and methylphenidate for inattention.

Atomoxetine is a novel nonstimulant medication used to treat ADHD. It acts by blocking presynaptic norepinephrine reuptake.

Atomoxetine is a novel nonstimulant medication used to treat ADHD. It acts by blocking presynaptic norepinephrine reuptake.

In one setting, atomoxetine was effective in treating both tics and ADHD in patients affected with both. In that study, significant increases were observed in pulse rate and nausea, and decreases in appetite and body weight.7

In one setting, atomoxetine was effective in treating both tics and ADHD in patients affected with both. In that study, significant increases were observed in pulse rate and nausea, and decreases in appetite and body weight.7

Obsessive–Compulsive Disorder

OCD is the second most common comorbidity in patients with TS. It is characterized by intrusive thoughts that produce uneasiness, apprehension, fear, or worry, and by repetitive behaviors aimed at reducing the associated anxiety.4

OCD is the second most common comorbidity in patients with TS. It is characterized by intrusive thoughts that produce uneasiness, apprehension, fear, or worry, and by repetitive behaviors aimed at reducing the associated anxiety.4

Approximately 20% to 30% of individuals with TS have an additional diagnosis of OCD. OCD is commonly accompanied by another psychopathology, such as depression, anxiety, ADHD, or aggression.

Approximately 20% to 30% of individuals with TS have an additional diagnosis of OCD. OCD is commonly accompanied by another psychopathology, such as depression, anxiety, ADHD, or aggression.

TS and OCD share several characteristics. Both are characterized by a juvenile or young adult onset, a waxing and waning course, and the presence of repetitive behaviors associated with premonitory urges.

TS and OCD share several characteristics. Both are characterized by a juvenile or young adult onset, a waxing and waning course, and the presence of repetitive behaviors associated with premonitory urges.

It can be difficult to distinguish compulsive behaviors from tics, and some individuals will display both. It is possible at times to distinguish compulsive behavior when the patient is able to explain that the ritualistic physical or mental affect serves to reduce intrusive thoughts or images rather than an uncomfortable feeling. However, this distinction is not easily made.8

It can be difficult to distinguish compulsive behaviors from tics, and some individuals will display both. It is possible at times to distinguish compulsive behavior when the patient is able to explain that the ritualistic physical or mental affect serves to reduce intrusive thoughts or images rather than an uncomfortable feeling. However, this distinction is not easily made.8

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree