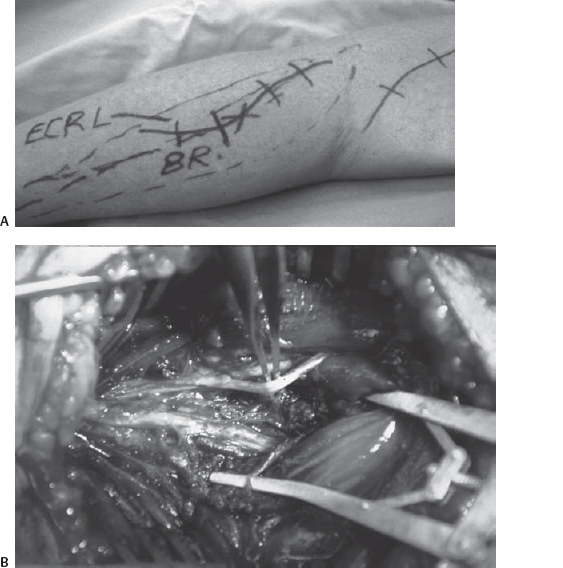

32 Radial Tunnel Syndrome A 48-year-old, right-handed treasury manager had been experiencing aching discomfort deep in her right posterolateral forearm for 14 months prior to her initial presentation. Her pain came on spontaneously with no specific physical activity or trauma. An episode of “lateral epicondylitis” had been successfully treated in the past. The pain had been radiating down her forearm to the wrist with exacerbation while squeezing objects, lifting, or even shaking hands. She had been a semiprofessional bowler for about 40 years who was now unable to lift the ball due to the pain. She could also no longer play golf. She denied any numbness or muscle weakness in her hand. Examination revealed normal muscle power and reflexes. Sensory exam revealed slightly altered sensation in the radial nerve distribution. There was a tender spot deep to the brachioradialis muscle ˜3 to 4 cm distal to the lateral epicondyle (which was not tender itself) (Fig. 32–1). The middle finger resisted extension, and resisted supination of the forearm reproduced her pain. Initially, she was managed conservatively with anti-inflammatory drugs, short periods of rest, and modified sports activity, with transient symptomatic relief. However, symptoms returned 1 year later when she tried to pick up a 3.5 lb bowling bowl. Her neurological examination remained completely normal. Due to the intractable symptoms and her wishes to pursue her professional bowling career, she opted for exploration and operative release of her radial nerve and posterior interosseous nerve (PIN) via an intermuscular approach between the brachioradialis and extensor carpi radialis longus muscles (Fig. 32–2). The nerve appeared grossly normal, and intraoperative electrophysiological studies were also normal. Follow-up over 1 year has confirmed relief of her symptoms even with previously provocative activities, and she has resumed bowling. Figure 32–1 Photo showing the forearm of the patient with radial tunnel syndrome and focal tender spot (X) deep to the brachioradialis (BR) and extensor carpi radialis longus (ECRL) muscles. Radial tunnel syndrome (RTS) At the level of the elbow, the radial nerve lies in an invariant intermuscular plane between the brachioradialis and brachialis muscles. Shortly thereafter, in the proximal forearm, the nerve divides into the smaller-diameter superficial sensory radial nerve (which lies deep to the brachioradialis as it courses down the forearm) and the larger motor branch, the PIN. The latter dives obliquely and deeply toward the posterior interosseous membrane, passing through a series of fibromuscular tunnels. The underlying pathology for RTS is assumed to be compression of the PIN at the following anatomical sites: Figure 32–2 (A) The incision between the brachioradialis and extensor carpi radialis longus muscles is outlined, as is the more classical incision for the more proximal and elbow-level radial nerve. (B) With adequate retraction of the extensor muscles, the radial nerve branching into the superficial sensory radial (with forceps underneath) and the larger and (seen to be) subdividing posterior interosseous nerve are exposed. The more superficial supinator muscle edge has already been divided to obtain the decompression and exposure seen. RTS is a pain syndrome characterized by pain over the lateral aspect of the proximal forearm, presumably related to entrapment of the PIN. This syndrome is often confused with tennis elbow, although patients can have both problems simultaneously. The diagnosis of RTS remains a clinical one, with no reliable objective criteria to differentiate among different pain syndromes in this region. Because of lack of objective criteria, the syndrome remains a controversial diagnostic entity. RTS is most frequently seen in workers who perform repetitive tasks requiring frequent forearm pronation-supination and elbow flexion-extension. The patient usually complains of lateral elbow pain. It may develop insidiously or more acutely after strenuous exercise of the elbow or forearm. The pain is typically dull and aching in nature, deep in the proximal forearm extensor muscle group with radiation usually down in the forearm. Night pain is a common complaint. Due to the resemblance of pain in tennis elbow, initial treatment is usually directed toward treatment of the latter. This treatment obviously fails, hence the term resistant tennis elbow, which is so commonly employed for RTS. The three important clinical characteristics of RTS are as follows: There are many causes of forearm pain, the vast majority of these being related to musculoskeletal conditions in and around the elbow joint. Pain following injury is usually a result of damage to soft tissue structures (muscles, ligaments, and tendons), joints, or bones and should not be diagnosed as RTS. Spontaneous onset of pain or pain following repetitive activity in the proximal lateral forearm is usually secondary to lateral epicondylitis or tennis elbow. This and similar inflammatory conditions must be entertained and treated, or excluded before the diagnosis of RTS is considered. Finally, there are patients with intrinsic pathology, such as a ganglion cyst or nerve sheath tumor, affecting the radial nerve in the proximal forearm that may present with pain in the lateral forearm and a paucity of neurological findings in the nerve distribution. Patients with these structural lesions may be diagnosed with appropriate imaging preoperatively or occasionally intraoperatively at nerve exploration. The role of electrophysiological study in the diagnosis of RTS is not clear. Part of the problem arises from a lack of uniform objective diagnostic criteria for the patient population. Most reports have found no abnormalities, although Rosen and Werner have demonstrated slowing of the motor conduction during forced supination of the forearm. Diagnosis is therefore based purely on the characteristic symptoms of pain and provocative findings, without neurological deficit. Considering the difficulty in diagnosing RTS with certainty, the initial step in treatment is an adequate period of conservative treatment for several months. This includes rest with a wrist dorsiflexion splint, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agents, and changes in activity, including avoidance of repetitive elbow extension, forearm supination/pronation with forceful wrist dorsiflexion. The occupations or hobbies involving the troublesome activities should be modified. If symptoms persist after conservative treatment, and other treatable causes including tennis elbow have been ruled out or appropriately managed, surgical release of the compressive pathologies may be considered. Ritts et al have advocated the use of local lidocaine block into the radial tunnel as a diagnostic confirmatory test for RTS. Although this may be useful, one concern is that an intraneural injection may result in an injection nerve injury. The goal of operation is wide and complete exposure with release of all the possible compressing structures as follows: There are three different approaches for exposure of the PIN at the proximal forearm. These include the proximal anterior at the elbow (between the brachioradialis and brachialis), proximal posterior intermuscular [longitudinal incision between the brachioradialis and extensor carpi radialis longus (ECRL)] muscle fibers, as shown in Fig. 32–2, and distal posterior (between ECRB and extensor digitorum) approaches. The differences lie in the approach to the PIN through the mobile muscle group in the radial forearm, which consists of the brachioradialis, ECRL, and ECRB. The authors prefer the intermuscular approach for most cases (Figs. 32–1 and 32–2). This provides access to the nerve where it is most likely to be compressed and with the least noticeable scar. The distal posterior approach between ECRB and extensor digitorum is preserved for cases with atypical tenderness at the distal edge of the supinator over PIN exit point or when initial proximal supinator division has failed to relieve the symptoms. In these cases pain and tenderness usually occur at the junction of the proximal and middle third of the forearm over the emerging PIN. This approach displays the distal two thirds of the supinator muscle and allows distal decompression of the PIN. Due to the difficulty in confirming the presumptive diagnosis of RTS in many patients, the treatment result remains variable. Patients typically present with prolonged duration of symptoms, usually due to delay in the diagnosis. However, the result can still be satisfactory. Good results have been reported in 65 to 70% of patients. It is of paramount importance to consider RTS when dealing with patients with forearm pain that has not responded to conventional therapies. Obviously, further objective criteria are required to reliably diagnose and subsequently treat the patients.

Case Presentation

Case Presentation

Diagnosis

Diagnosis

Anatomy

Anatomy

Characteristic Clinical Presentation

Characteristic Clinical Presentation

Differential Diagnosis

Differential Diagnosis

Diagnostic Tests

Diagnostic Tests

Electrophysiological Studies

Management Options

Management Options

Outcome and Prognosis

Outcome and Prognosis

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree