Radiation Physics and Safety

Glenn R. Rechtine II

Brian D. Giordano

RADIATION PHYSICS AND SAFETY

The use of x-rays has been a mainstay of medical practice since William Roentgen’s discovery in 1895. In fact, over time, the use has continued to grow. There are 20 times as many CT scans done today as in 1980 (1). As reported by Steve Sternberg (2) on the front page of the November 29, 2007, USA Today, overuse of CT scans could result in three million unnecessary cancers. As we move to progressively more minimal access surgeries, the use of intraoperative fluoroscopy is increasing as well. So, it becomes increasingly apparent that appropriate utilization of x-rays is necessary. Knowledge of the potential risks and benefits is necessary for good medical practice. Unfortunately, there is very little, if any, routine education toward this end in medical school or residency.

BASIC PHYSICS

Ionizing radiation used in medical imaging is quantified by several criteria (see Table 22.1).

As the x-ray machine produces the beam, the kVp affects tissue penetration and contrast, while mA affects the total amount of x-ray production and more. The radiation that penetrates the patient and reaches the image intensifier or film produces the image. This is a very small amount of the total radiation produced. Some radiation is absorbed by the patient; this is what produces the patient dose, and some radiation is scattered into the area surrounding the patient. See Table 22.2 for typical patient radiation doses during medical imaging.

We must also consider scattered radiation. Scatter is responsible for the majority of the occupational exposure of medical personnel.

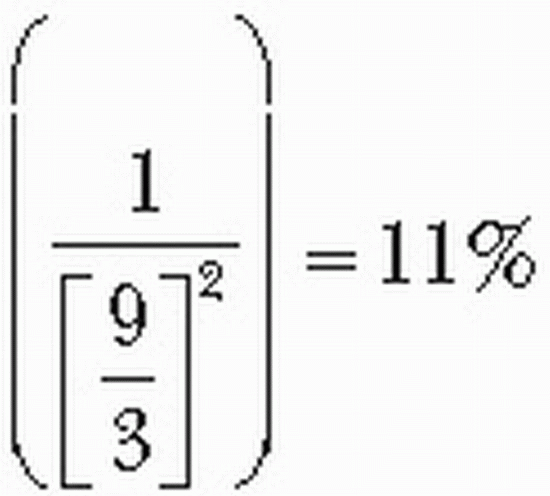

The x-ray beam is considered a point source. As such, the inverse square law predicts the effect of increasing distances from the beam; an object three times as distant will receive one-ninth of the radiation. Therefore, moving even a small distance away makes a large difference in exposure. Equation 1 shows that if the surgeon moves from 3 to 9 inches from the source, exposure decreases only by 11%.

Equation 1: Exposure Reduction after Moving Away from a Point Source

CHRONIC AND ACUTE RADIATION EXPOSURES

Why do we even need to worry about radiation exposure? In the 1950s, fluoroscopes were placed in shoe stores so patrons could use the x-ray to buy the correct size shoe. Dentists used to routinely hold the film in a patient’s mouth when taking dental x-rays. Over time, we found that what was considered inconsequential exposure could have negative consequences.

We know that when someone is exposed to large doses of radiation, immediate and predictable medical effects occur.

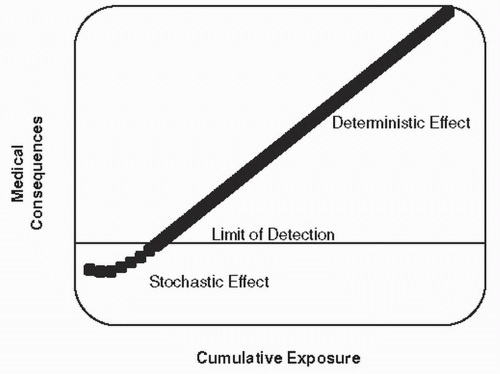

Examples of this are skin erythema and ulcerations. This represents the deterministic effect. When we plot a direct exposure to consequence graph, at low levels of exposure, the linearity breaks down. This represents the stochastic or nonlinear effect (see Fig. 22.1). Doses below the limit of detection indeed have an effect. The medical practitioner using poor technique is at risk of multiple low-level exposures. Since exposure is cumulative, poor technique can have consequences years and sometimes generations in the future. This can be expressed as increased risks of cataracts, cancer, or birth defects (see Fig. 22.1).

Examples of this are skin erythema and ulcerations. This represents the deterministic effect. When we plot a direct exposure to consequence graph, at low levels of exposure, the linearity breaks down. This represents the stochastic or nonlinear effect (see Fig. 22.1). Doses below the limit of detection indeed have an effect. The medical practitioner using poor technique is at risk of multiple low-level exposures. Since exposure is cumulative, poor technique can have consequences years and sometimes generations in the future. This can be expressed as increased risks of cataracts, cancer, or birth defects (see Fig. 22.1).

TABLE 22.1 Measuring Ionizing Radiation | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

RADIATION EXPOSURE TO THE PATIENT AND SURGEON

Several parameters of imaging technique can affect radiation exposure to the patient and surgeon. The size of the body area to be imaged, or field size, use of magnification, proximity to the radiation source, and angulation of the beam affect radiation exposure.

FIELD SIZE

The field size is the body surface area exposed to radiation. Increasing the field size increases the amount of the patient’s body exposed. It also causes more scatter, which degrades the image. The scatter is also responsible for the majority of the exposure to medical personnel.

Collimation is the process by which the size of the field is restricted. Collimating the field is good medical practice, as it decreases the exposure to the patient, increases the quality of the image, and reduces the exposure of others in the vicinity.

TABLE 22.2 Patient Radiation Exposure during Medical Imaging | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

MAGNIFICATION

The magnification feature of an image intensifier artificially manipulates a small radiation input area into a large output area. This requires four times as much radiation output and therefore patient exposure to obtain an image.

PROXIMITY AND POSITION RELATIVE TO THE INSTRUMENT

Common sense dictates that medical personnel keep their hands and other body parts outside the direct x-ray beam. When doing so, the risk of exposure is from scatter radiation. Under most circumstances, the exposure is highest closest to the source. In a lumbar surgery model, the surgeon exposure standing on the x-ray source side of the table was 52 mrem/min. When standing on the image intensifier side, this was reduced to 2 mrem/min (3).

This is consistent when large portions of the body are imaged (4). When the cervical spine was imaged, the exposure was similar on both sides. This is presumably because the x-ray beam is larger than the neck and a portion of the radiation gets to the image intensifier side without being attenuated by the patient (5).

ANGULATION OF THE X-RAY BEAM

Angulation of the x-ray beam to produce oblique images requires higher radiation doses and thus more scatter radiation to expose the personnel.

EFFECTIVE DOSE

In 1975, Jacobi proposed a new way to assess radiation exposure among occupational workers. The relative radiation sensitivity of the specific organs was estimated to try to better predict the stochastic carcinogenic potential of long-standing, occupational exposure (6). For example, the gonads are some of the most sensitive tissues and are therefore given a higher rating than skin or muscle. This helps to quantify the risk of occupational exposure. There are still several weaknesses with this approach. The relative weighting factors are estimates and not based on hard data. In 2007, the International Committee on Radiation Protection (ICRP) changed the relative values with Publication 103 (7). This now places a higher value on exposure to the breast and salivary glands with a concomitant decrease in the value for the gonads. The effective dose does not take into effect other local changes associated with exposures other than cancer and death. For extremities, equivalent dose is used for occupational exposure for this reason. This is more of a total radiation exposure without using the weighting factor used in effective dose calculations.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree