35

CHAPTER

![]()

Reproductive Issues

Lynn Liu

HISTORY

Historically, people with epilepsy (PWE) around the world have been stigmatized due to misconceptions about seizures. In ancient times they were typically thought to be possessed by evil spirits and therefore were feared. The belief that seizures were contagious resulted in isolation from the rest of society. PWE were also legally denied the right to go to public places such as restaurants, theaters, or other recreational areas. Based upon these misconceptions, the 17th-century treatment for women with epilepsy (WWE) included hysterectomies. Laws were established over two hundred years ago that PWE could not marry or procreate. In 1956, 17 states in the United States still prohibited PWE from marrying, and it was not until 1980 that the last state repealed this law. During the same time period, laws enforcing eugenic sterilization for PWE existed; the last state repealed this law in 1970 (1). As a result, the issue of reproduction for PWE is a fairly modern concept.

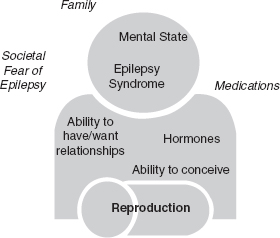

Even with progress to the legal system, social awareness and acceptance of comorbid mental health disorders and improved treatment for epilepsy, the physiologic barriers to reproduction persist at various levels, including the epilepsy syndrome itself, hormones, and medications. PWE feel isolated and have limited interactions with other people. In general, they have reduced quality of life (QOL), which diminishes their desire to have intimate relationships and even consider having children. Epilepsy syndromes that start earlier in life impact social and physiological development compared with adults-onset epilepsy. Both men and women with epilepsy have more endocrine dysfunction compared to the general population and as a result have reduced libido and fertility. The medications they take to control their seizures further alter mood, seizure frequency, hormones, or interact with other medications. Women with epilepsy have additional fears. Family planning and choosing the appropriate contraceptive methods are topics they feel providers try to avoid. They worry about their children inheriting their epilepsy, the effect of their medications on a developing fetus, and the additional concerns about undergoing a pregnancy and delivery. Supports and precautions should be considered for the mother with epilepsy raising children. Misinformation in the medical community and society persist even in the face of established practice parameters for the management of WWE and public campaigns. This chapter reviews some of the issues related to reproduction in men and women with epilepsy.

RELATIONSHIPS

In order for anyone to develop a successful relationship, they need positive self-esteem and have an appropriate mental state with adequate social supports. PWE have higher rates of both depression and anxiety compared to the general population in part due to the unpredictable nature of seizures and the limitations society sets on PWE. Physiological consequences of seizures, both generalized and focal, along with their treatments alter the neurologic circuitry of mood and behavior. Psychosocial factors that restrict PWE from having meaningful relationships include reduced independence and lower socioeconomic status. Both factors sustain the cycle of limited social interaction and isolation (Figure 35.1).

Mood Disorders

Depression and anxiety have been estimated to affect 30% to 50% of PWE; a higher rate compared with the general population, which ranges from 7.2% to 20% in the literature (2). The wide range of percentages depends on whether the population studied was based on community or tertiary care centers where the epilepsy syndrome may be more difficult to control. Their risk of suicide is estimated to be 10-fold over the general population especially if they feel hopeless (2). Theories why PWE may be more vulnerable to depression arise from the unpredictable nature of an uncontrollable adverse event: the seizure. This results in a poor health-related locus of control and learned helplessness. With this, they tend to have lower self-esteem. They use primitive coping mechanisms such as escape-avoidant and wish-fulfilling fantasy. Mental health providers unfamiliar with the diagnosis of epilepsy have concerns that starting antidepressant medications will increase the likelihood of a seizure, and as a result, many PWE suffering from depression are undertreated.

FIGURE 35.1 Pictorial representation of how epilepsy does not effect the individual alone, but it also affects the way they feel about themselves and their interactions with family and society.

![]()

Epilepsy Syndrome and Mood

The type of seizure influences the rates of depression and anxiety both positively and negatively. The diffuse discharge of generalized seizures can exert an effect on depression much like electroconvulsive therapy, and with improved seizure control, increased mood issues can emerge. Focal seizures, particularly seizures arising from the temporal region, activate the limbic system. Amygdalar seizures initially get misdiagnosed as panic attacks because they are characterized by episodic fear, especially if they do not progress to confusion and staring, indicating an evolution to the complex phase of a seizure. Episodic stimulation of the limbic circuitry has been associated with both elevated and depressed mood, both pre- and postictally. Within the frontal lobe, seizures arising from the cingulate gyrus activate in the limbic system as well. Prefrontal cortex seizures have been associated with altered behavioral regulation. Knowing the localization of the seizure can provide further understanding to the management of the patient’s overall well-being.

Most of the medications used to treat seizures have common side effects of sedation, fatigue, and anhedonia. Nonetheless, seizure medications have been noted specifically to alter mood beyond the improved control of seizures. Mental health providers use seizure medications to stabilize mood disorders independent of the diagnosis of seizures.

Psychosocial Factors

PWE tend to have lower academic achievement, lower financial status, and limited transportation. Furthermore, PWE are less likely to have friends, steady relationships, or marriage. If their epilepsy begins while they are still in school, the seizure frequency and medications impact their educational experience. Lower educational status, limited transportation, work restrictions, and increased absenteeism all result in less employment. They remain dependent on their families for support. If they marry, the person with epilepsy takes on the dependent role in the relationship and feels limited in their independence. However, it has been observed that after successful surgery for medically intractable epilepsy, improved seizure control leads to a change in marital dynamic, often leading to divorce due to increased independence for the person with epilepsy.

Although culturally specific, surveys worldwide suggest that PWE are less likely to marry and more likely to divorce compared to the general population. The stability of the marriage typically has been associated with later age of onset of the epilepsy and better seizure control. The decrease in marriage rates cannot be explained by the increased rates of developmental delays and cognitive impairment completely. PWE discuss whether to disclose the diagnosis before marriage; most do not. In Canada, marriage rate were estimated to be 59% of expected in men with epilepsy and 83% of expected in women especially if the epilepsy began before the age of 20 (3). In a study conducted in India, one of the last countries to repeal the marriage laws, the rates were even lower: 46.6% in men and 46.7% in women (3). In an opinion survey about marriage and raising children, people in Hong Kong agreed that PWE should be able to marry and have children, but they would discourage their children from marrying someone with epilepsy (3).

SEXUALITY

Once a person with epilepsy commits to an intimate relationship, about one- to two-thirds encounter higher rates of sexual dysfunction. The majority experience hyposexuality with decreased libido, which is the desire or interest in sexual activity, and diminished potency, which is the physiologic arousal that occurs during sexual activity. In men, these changes are externally evident as decreased penile rigidity and tumescence. A medical evaluation should clarify if the altered responses are a result of a mood disorder or a physiological disorder. The presence of nocturnal erections during rapid eye movement sleep indicates normal physiology and distinguishes the cause of decreased potency to be related to emotional issues. WWE report that they do not experience orgasms and have increased dyspareunia, vaginismus, and reduced vaginal lubrication with sexual intercourse. Both men and women with epilepsy have reduced blood flow to genital tissues in response to visual erotic stimuli compared to age-matched controls.

Epilepsy Syndrome and Sexuality

Some associate intimacy with fear because hyperventilation and physical exertion may result in a seizure. Others who have sexual auras have negative associations with seizures. Automatisms of a sexual nature such as masturbation or removing clothing postictally have been interpreted as hypersexuality or paraphilias historically in the literature. The advent of video EEG (vEEG) monitoring documenting the simultaneous electrographic pattern documents the ictal nature of these acts. Repeated stimulation of the limbic system by seizures can alter sexuality. Bilateral mesial temporal injury is associated with Kluver-Bucy syndrome.

The cause of altered sexuality has a complicated network of etiologies related to hormones, medications, and seizures. PWE have reduced levels of sex steroids especially testosterone and estrogen, which are necessary for both men and women in appropriate amounts for maturation, sexual desire, and reproductive fitness. Seizure medications, especially those that induce hepatic enzymes, reduce the bioavailability of these sex hormones. Seizure types can change the regulation of hormonal secretion perpetuating the cycle.

Medications and Sexuality

Starting in the 1970s to 1980s, researchers observed that the use of seizure medications influenced the reproductive endocrine system, resulting in reduced sexual function (4). Both gonadal hormones and many seizure medications are metabolized through the cytochrome P450 (CYP450) and specifically the 3A4 isoenzyme. When agents such as phenytoin, carbamazepine, phenobarbital, and primidone (PRM) are used, a couple of things happen concomitantly: increased metabolism of the sex hormones and an increased production of sex hormone binding globulin (SHBG). This protein binds circulating sex steroids to make the free fraction less bioavailable and not available to act on the appropriate end organ. The total levels may still be within the normal range, but the free level will be lower. Not only are estrogen and testosterone levels affected, so are dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEAS), a precursor to both androgens and estrogens. As a result of the lower active hormone levels, pituitary feedback also diminishes.

In contrast, valproic acid (VPA) inhibits hepatic enzymes and yet it also has been associated with sexual dysfunction in both men and women with epilepsy. The mechanism studied in the 1990s in WWE who also have menstrual dysfunction suggest an increased rate of polycystic ovarian syndrome (PCOS). This syndrome is evident if the use of VPA began earlier than 20 years and for those who gain weight. VPA changes androgen levels before puberty and therefore could influence maturation in young girls.

Medications that do not influence the CYP450 system significantly do not cause as many hormonal changes. Oxcarbazepine at low doses is not considered an enzyme inducer, but at higher doses it can induce CYP450. Switching from carbamazepine to low-dose oxcarbazepine can reverse some of the endocrine dysfunction, but its effect on reproductive hormones is dose related. Lamotrigine has not been shown to alter the reproductive endocrine system in contrast to animal studies. In fact, switching to lamotrigine from VPA seems to reverse some of the observed endocrine dysfunction in both testosterone and insulin within a year of changing medications. Data are limited on the newer medications and none of the other seizure medications have been rigorously studied in this same manner.

Hormones and Sexuality

In addition to their reproductive functions, gonadal sex steroids also have neuroactive properties. Estrogen in animal models stimulates glutamate and inhibits gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) receptors. It has also been demonstrated to alter neuronal architecture and increase the number of dendritic spines. All these changes can lead to a proconvulsant state. In contrast, progesterone inhibits glutamate and stimulates GABA, resulting in a relatively protective state. The actions of testosterone on seizures are not clear. Animal models and human tissue samples also note an upregulation of androgen receptors in the presence of enzyme-inducing medications and therefore increased sensitivity to neuroactive steroids. Aromatase (CYP19), another CYP450 enzyme, converts androgens to estrogen and acts on the cerebral cortex. Several seizure medications can inhibit its actions and reduce the conversion of testosterone to estrogens; the end result is an increase in testosterone and less estrogen levels in women.

The brain regulates the hypothalamic–pituitary–gonadal axis with regular pulsatile stimulation to the hypothalamus. Pituitary hormones are necessary for normal sexual function. Synchronized discharges of generalized seizures disrupt the regulation by causing a surge in prolactin levels within 20 minutes of the seizure. In animal models, temporal lobe seizures and interictal epileptiform discharges also alter the regular pulsatile stimulation of the hypothalamus, which in turn also increases prolactin secretion. One function of prolactin is to provide sexual gratification by inhibiting dopamine released during sexual intercourse. Chronic hyperprolactinemia has been associated with hyposexuality.

Owing to the personal nature of sexuality, providers rarely ask or discuss the topic despite the implications to quality of life. In men with erectile dysfunction, evaluation for alternative causes such as cardiovascular disease, diabetes, or depression should be initiated or opt for treatment with phosphodiesterase type 5 (PDE5) inhibitor such as sildenafil. In the evaluation and treatment of women, just as in men, it is important to explore whether the sexual dysfunction is related to emotional well-being or physiological changes. The treatment of hyposexuality in women has not been well studied and there are few recommendations other than sex therapy and lubrication. Working with a reproductive endocrinologist and replacing necessary hormones can also be of benefit.

FERTILITY

Fertility rates have been noted to be lower for both men and women with epilepsy compared to their sibling controls. Fertility in married WWE is 69% to 85% expected number of offspring especially those who have temporal lobe epilepsy (5). WWE have an increased frequency of menstrual dysfunction. Men with generalized epilepsy have 36% fertility rate of their siblings. Men with epilepsy have decreased sperm counts with abnormal morphology and impaired motility. Hypogonadism can be related to low testosterone levels due to reduced gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH). Hyperprolactin states can result in reduced reproductive function. There may be cultural influences as well, since in Iceland there are no noted changes in fertility. Factors that seem to influence fertility are localization-related epilepsy, especially early age of onset, hormonal regulation, and medications used to treat seizures.

Epilepsy Syndrome and Fertility

Menstrual disorders in WWE are more frequent in women who have more seizures. The characteristics of the menstrual dysfunction may have lateralized differences. Left temporal lobe seizures increase GnRH release, which results in increased lutinizing hormone (LH) and follicle stimulating hormone (FSH) that can cause altered follicular development in the ovaries and increasing testosterone levels in women as a potential mechanism for polycystic ovarian syndrome (PCOS). In contrast, right temporal lobe seizures results in decreased GnRH and thus LH and FSH resulting in lower estrogen levels and increased prolactin levels. The clinical consequence results in hypothalamic amenorrhea and possibly premature menopause that begins before 30 years of age.

Medications and Fertility

Epilepsy and the use of VPA both have been independently associated with PCOS. Studies have demonstrated increased rates of PCOS in WWE. On further evaluation, it was suggested that this syndrome was more frequently associated with left temporal lobe epilepsy and the use of VPA in contrast to the use of lamotrigine. The frequency of PCOS in WWE was estimated between 10% and 20% versus 5% and 6% in the general population (6). Recently this association has been called into question because of different study designs and different definitions of polycystic ovaries (PCO) and PCOS. PCO have more than 10 follicular cysts sized between 2 and 8 mm that are located in the periphery of the ovaries and have increased ovarian stroma or size. This finding can be identified by ultrasound in the setting of menstrual irregularity due to erratic or infrequent ovulation. PCOS defined by an NIH consensus statement includes ovarian dysfunction and hyperandrogenism or hyperandrogenemia exclusive of other endocrine abnormalities. Clinical manifestations include menstrual dysfunction, infertility, hirsutism, and obesity with hyperinsulinemia. Three hypothetical mechanisms include (a) increased LH pulse frequency and amplitude, resulting in retained follicular cysts and continued androgen production that is not converted to estrogens by aromatases, (b) primarily ovarian failure, and (c) reduced sensitivity to insulin (6).

Hormones and Fertility

The relationship between sex steroid hormones and seizures has been well established since Gowers. Some women observe that their seizures vary in frequency based on the phase of their menstrual cycle: catamenial epilepsy. On evaluation, WWE tend to be most vulnerable when the estrogen/progesterone ratio is higher. Studies of this phenomenon categorize vulnerable timeframes into three periods identified as C1, C2, and C3. Two timeframes of ovulatory cycles as progesterone levels are falling rapidly include peri-ovulation (C1) when there is an LH surge and a rise in estrogen levels while progesterone levels remain low and peri-menstrually (C2) (7). For a variety of reasons WWE have a lower proportion of ovulatory cycles and a higher proportion of anovulatory cycles compared to their sibling controls. The vulnerable time frame for seizures during an anovulatory cycle, when there is an inadequate luteal phase, ranges from ovulation to the onset of menses (C3). In order to establish the diagnosis, a woman should maintain both a seizure diary and a menstrual calendar and chart the relationship between the two for at least three cycles. They can monitor which cycles are ovulatory and which are not with over-the-counter ovulation kits. Sharing this information with her provider may open discussions in treatment options.

CONTRACEPTION

Women use hormonal agents for a variety of indications: family planning, dysfunctional uterine bleeding, and menstrual cycle regulation. Hormonal preparations come in a variety of forms including pills, patches, and hormonally impregnated devices. This decision to choose an effective and tolerable method in a woman with epilepsy has added considerations including the effect of hormones on seizure control, the effect of seizure medications on hormonal contraceptives, and the effects of hormonal contraceptives on seizure medications. With the variety of types and forms available, the decision may need to be coordinated with a primary care provider or gynecologist.

The majority of oral contraceptive preparations are composed of a combination of an estrogen and a progestin. The estrogen component is the synthetic agent, ethinyl estradiol (EE), and the dose can vary by preparation. Maintaining steady levels of EE inhibits the LH surge necessary for ovulation, thereby preventing pregnancy. Additional changes include increasing the thickness of the cervical mucus and providing an additional barrier, altering the endometrial lining that reduces the likelihood of implantation. The progestin component can vary in type and dose. In the phasic preparations, there may be 7 days of placebo pills that mimic a regular menstrual cycle. In the extended preparations, the cycle can be extended to once every 3 months to once a year. These preparations have advantages for women who have catamenial epilepsy. Common side effects include nausea, headache, breast tenderness, and breakthrough bleeding. However, venous thromboembolism (VTE) represents the most serious side effect and this risk increases in the setting of advancing age, smoking, and prior history of VTE. Historically, the dose of EE has been reduced to minimize these side effects.

Medications and Hormonal Contraception

Of greater concern to WWE is the interaction of AEDs on combined oral contraception (COC) when it is used to prevent pregnancy. In the general population, estimated failure rates are 0.3% under ideal conditions and up to 8% with real-world experience (8). The consequences of an unintended pregnancy in a woman with epilepsy on medications used to treat seizures are the increased risks of pregnancy and teratogenicity from the medications. Proper counseling should be given before starting any hormonal contraception. To compound the issue further, providers who treat WWE may not be familiar with the interactions between seizures medications and combined oral contraceptives and avoid the discussion or provide misinformation.

Lower hormone levels put women at risk of becoming pregnant. If a woman on a CYP450-inducing agent chooses a combined oral contraception (COC), then based on guidelines from the American Academy of Neurology (AAN) and American Epilepsy Society (AES), the ethynil estradiol should be increased to 50 mg or the frequency of IM injections should be more frequent (Table 35.1). Currently the patches only have one dosage form and therefore are not recommended for this situation. Breakthrough bleeding mid-cycle may indicate low estradiol levels. When used exclusively for contraception, a second form of birth control such as barrier methods (eg, condoms (male and female), diaphragm, and cervical caps) and sterilization may be necessary to prevent pregnancy. Most women prefer this method exclusively due to the increased availability, no prescription, and no interactions despite the increased failure rate. Medications that inhibit hepatic enzymes do not have any documented effect on COC effectiveness so doses of medications do not need to be adjusted.