Chapter 52 Retropleural Approach to the Ventral Thoracic and Thoracolumbar Spine

Two of the most widely used approaches to the ventral thoracic and thoracolumbar spine are the transpleural thoracotomy and the lateral extracavitary approach.1,2 Each approach has its advantages and disadvantages. The major advantage of the ventrolateral transpleural thoracotomy is that it provides unparalleled exposure of the ventral vertebral column over several segments. Nevertheless, this exposure has several disadvantages. First, this approach is characterized by an extensive incision and soft tissue dissection that are necessitated by a deep operative field. Second, because with this approach the chest cavity is entered from the ventrolateral chest quadrant, significant retraction of the unprotected lung is required. Finally, identification and decompression of the ventral spinal canal are also problematic, because the rib head partially obscures the spinal canal and the epidural veins are difficult to control via this trajectory. The aforementioned factors can create a less secure operative environment, increase surgical morbidity, and hinder the attainment of the surgical objective(s).

A retropleural thoracotomy, ideally, is more suited for a ventral exposure of the thoracic and thoracolumbar spine.3–7 Similar to the situation in ventrolateral thoracotomy, the line of vision provided with a retropleural thoracotomy is ventral to the ventral aspect of the spinal canal, but because the chest cavity is entered more dorsally, there is a significantly shorter distance to the ventral vertebral column and canal. The extrapleural nature of the dissection allows safer and more secure lung retraction and avoids postoperative tube thoracostomy placement. This approach allows for earlier identification and entry into the lateral spinal canal, via a resected pedicle. It greatly facilitates ventral spinal canal decompression through the disc space and vertebral bodies. Unlike the lateral extracavitary approach, however, mobilization or sacrifice of the foraminal neurovascular structures is avoided. Thus, retropleural thoracotomy represents a hybrid surgical approach, incorporating the advantages of both standard transpleural ventrolateral and dorsolateral extrapleural approaches while avoiding their limitations.

Surgical Technique

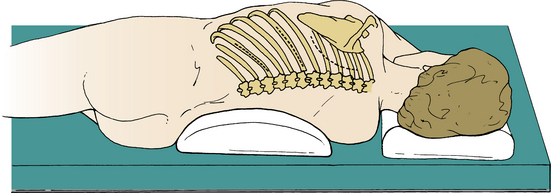

After appropriate arterial and venous line access has been established, induction and intubation are performed. A double-lumen tube is used for lesions above the T6 vertebral level. An epidural catheter may be placed after intubation or at the conclusion of the procedure for postoperative pain management. A broad-spectrum antibiotic is usually administered 30 minutes before the skin incision, and this may be continued for two postoperative doses. The patient is carefully turned into a lateral position on a beanbag chair, with a small, soft roll under the dependent axilla. The upper arm is supported on a pillow or sling. The lower leg is slightly flexed at the hip and knee to help secure the position. All bony prominences and subcutaneously coursing nerve trunks must be well padded. The ulnar nerve at the elbow and the peroneal nerve at the fibular neck are particularly vulnerable areas. Thoracolumbar lesions should be centered over the kidney break. The skin incision is planned according to the level of exposure. For midthoracic lesions (T5-9), a 14-cm skin incision should extend from a point 4 cm off the dorsal midline to the dorsal axillary line. Extension of the incision toward the midaxillary line expands ventral access and may be required in some cases (Fig. 52-1, center incision). A curved incision that parallels the medial and inferior scapular border is used for upper (T3-4) thoracic lesions (see Fig. 52-1, right incision). For thoracolumbar exposure (T10-L2), the incision should parallel the rib one spinal segment above the pathologic level because of the more caudal inclination of the proximal portion of the lowest ribs (see Fig. 52-1, left incision). Therefore, whereas the approach to a T7-8 disc is exposed through the T8 rib bed, a T12 lesion is approached through the bed of the T11 rib.

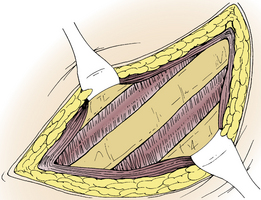

The skin incision is carried down to the rib (Fig. 52-2). A 10- to 12-cm rib segment, extending from the costotransverse ligament to the dorsal axillary line, is subperiosteally exposed and removed with rib shears (Fig. 52-3). The exposed bone surfaces are waxed. Note that the proximal 4 cm of the rib, extending from the costotransverse articulation to the rib head, has yet to be removed. The bed of the resected rib is now inspected. Muscle fibers of an inconstant subcostal muscle may be seen. At thoracic levels above T10, the endothoracic fascia will be identified in the rib bed. The endothoracic fascia is analogous to the transversalis fascia of the abdominal cavity.8 Both types of fascia line the walls of their respective visceral cavities and are reflected onto the surface of the diaphragm. The endothoracic fascia is tightly applied to or is continuous with the inner periosteum of the rib and vertebral bodies. The parietal pleura maintains its attachment to the chest wall through a surface tension seal with the inner surface of the endothoracic fascia. The intercostal vessels, nerves, and sympathetic chain are contained within the endothoracic fascia. Although only a potential (subendothoracic) space exists between the endothoracic fascia and the parietal pleura, a small amount of fluid and loose adipose tissue is occasionally identified, particularly dorsally near the rib head and vertebral bodies. Because the endothoracic fascia is continuous with the inner periosteum of the rib, it may be inadvertently torn during rib dissection and removal. This is common in older patients. If the endothoracic fascia is intact, it should be incised in line with the rib bed (Fig. 52-4). The underlying parietal pleura is bluntly and widely separated from the endothoracic fascia, either manually or with a Kittner (peanut) clamp (Fig. 52-5). The endothoracic fascia incision is continued dorsally to the margin of the cut surface of the remaining proximal rib. Blunt dissection of the pleura off the proximal rib head extends dorsally to expose the vertebral bodies and disc space. When the ventral convex border of the vertebral body has been exposed, a self-retaining, table-mounted retractor maintains exposure of the vertebral column (Fig. 52-6).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree