31 Rheumatoid Arthritis of the Cervical Spine

KEY POINTS

Introduction

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is a chronic inflammatory disease that commonly presents with polyarthropathy, systemic symptoms, and cervical spine involvement. Some reports state that RA was first described by A.J. Landre-Beauvais, whereas others credit Robert Adams. Robert Adams described it as a separate entity from gout in the nineteenth century in Dublin. The term rheumatoid arthritis was coined by A.B. Garrod, and its predilection for the cervical spine was first highlighted by his son, A.E. Garrod.1

Epidemiology and Natural History

The prevalence of RA is up to 1% to 3% of the United States population. It is commonly seen in those 40 to 70 years of age, and the male to female ratio is approximately 1:3. Symptomatic cervical spine disease is present in 40% to 80% of patients with RA. Up to 86% of patients have radiographic evidence of cervical spine involvement. In a study that evaluated patients with RA undergoing hip and knee arthroplasty, over 60% had cervical spine involvement.2

Pathophysiology

Rheumatoid arthritis is a chronic immune-mediated response. Unknown antigens, perhaps viral, trigger a cell-mediated response resulting in the release of various inflammatory mediators. The inflammatory response is put into motion by the CD4+ lymphocytes, which activate the B lymphocytes to produce immunoglobulins that are found in the rheumatoid synovium. The rheumatoid synovium contains two distinct cell types: type A cells are morphologically similar to macrophages and type B cells are similar to fibroblasts. Type A cells are mainly for phagocytosis, whereas type B cells are highly metabolic and are equipped with organelles for protein synthesis. These cells produce multiple inflammatory mediators, such as TNF-α, metalloproteinases, collagenases, progelatinases, and IL-1.3 These mediators are targets for DMARDs.

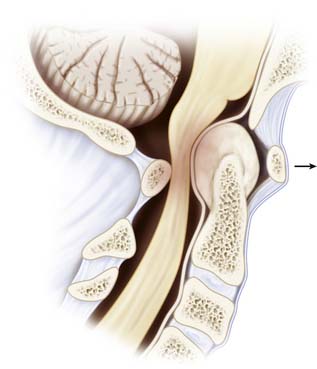

Atlantoaxial instability is the most commonly seen (40% to 70%) affliction in the rheumatoid spine. The formation of periodontoid pannus leads to erosion of the transverse, alar, and apical ligaments. The weight of the head combined with flexion and extension at this level leads to stretching and eventual rupture of these ligaments. The odontoid itself and the lateral atlantoaxial articulations are commonly eroded as well, leading to further instability. Depending on the pattern and location of bony and ligamentous erosion, the subluxation may present as anterior, posterior, lateral, or rotational. Anterior is the most common (70%). Anterior subluxation of 0 to 3 mm is normal in adults, 3 to 6 mm is suggestive of instability and rupture of the transverse ligaments, and greater than 9 mm suggests gross instability and incompetence of all periodontoid stabilizing structures. Posterior subluxation is rare and may be associated with a defect in the anterior C1 arch or fracture or erosion of the odontoid. Lateral subluxation is defined as 2 mm of lateral displacement at the atlantoaxial articulation.

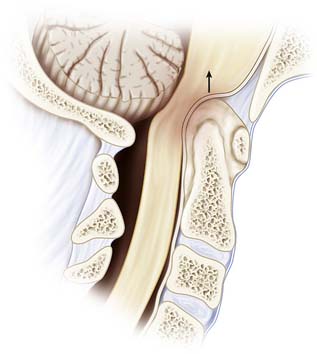

Cranial settling, or basilar invagination, is a late finding that is due not only to ligamentous and capsular erosion, but mainly to bone and cartilage destruction of the atlantoaxial and atlantooccipital articulations (Figure 31-1). Cranial settling carries an ominous prognosis. Anterior compression of the medulla oblongata can lead to injury to cranial nerve nuclei, syringomyelia, or obstructive hydrocephalus. Sudden death may also occur due to brainstem compression or vertebrobasilar dysfunction.

Clinical Presentation

Careful examination is necessary, as neurological deficit can be masked by weakness from peripheral joint involvement. Myelopathy is progressive and often goes unnoticed because of peripheral involvement. Fine motor skill deterioration may be mistaken for hand involvement, or decreasing ambulatory status may be mistaken for large joint involvement. As patients become more myelopathic, prognosis worsens. The Ranawat grading system for neural assessment may be used to appropriately classify the severity of myelopathy and can be used as a prognostic tool (Table 31-1).

TABLE 31-1 Ranawat Grading Scale for Myelopathy

| Grade | Severity |

|---|---|

| I | Normal |

| II | Weakness, hyperreflexia, altered sensation |

| IIIA | Paresis and long-tract signs, ambulatory |

| IIIB | Quadriparesis, nonambulatory |

Radiographic Analysis

Plain Radiographs

Radiographic criteria for RA, as defined by Bland, include atlantoaxial subluxation of 2.5 mm or more, multiple subaxial subluxations, disc space narrowing without osteophytes, vertebral erosions, eroded (pointed) odontoid, basilar impression, apophyseal joint and facet erosions, osteopenia, and secondary osteosclerosis from occiput to C2, which may indicate degenerative change.

The lateral neutral, flexion, and extension films are an effective screening tool for detecting cervical involvement in RA. They allow for identification of static and dynamic instability in the upper and lower cervical spine. Anterior atlantodental interval (AADI) and posterior atlantodental interval (PADI) can be determined from these views. These two values are used to determine atlantoaxial instability. The AADI is measured from the posterior aspect of the anterior arch of the atlas to the anterior surface of the dens. Anatomically, the transverse ligament holds the odontoid process against the anterior arch of the atlas and acts as the primary stabilizer of the atlantoaxial articulation. As the transverse ligament attenuates, there is more motion between the odontoid and atlas, which manifests on flexion/extension films as dynamic instability. An AADI greater than 6 mm has been used as a sign of instability, whereas an AADI greater than 9 mm has been considered an indication for surgery. However, the use of the AADI in management has been questioned, as erosive changes and anatomic abnormalities may be present. Boden et al 4 showed that the PADI may be more reliable and a better predictor of neurological recovery after surgical stabilization. Patients with a PADI greater than 14 mm experienced a higher rate of neurological recovery, while those with a PADI less than 10 mm had no recovery (Figure 31-2). Posterior subluxation may also be seen on lateral radiographs and should raise the suspicion of an absent or fractured odontoid. The open-mouth view is useful to identify lateral subluxation, which is defined as greater than 2 mm of lateral displacement at the C1-2 lateral articulation.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree