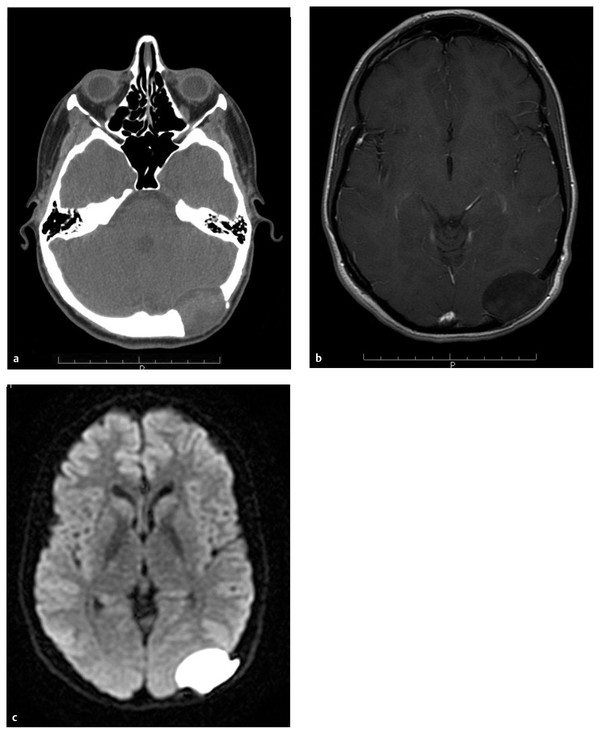

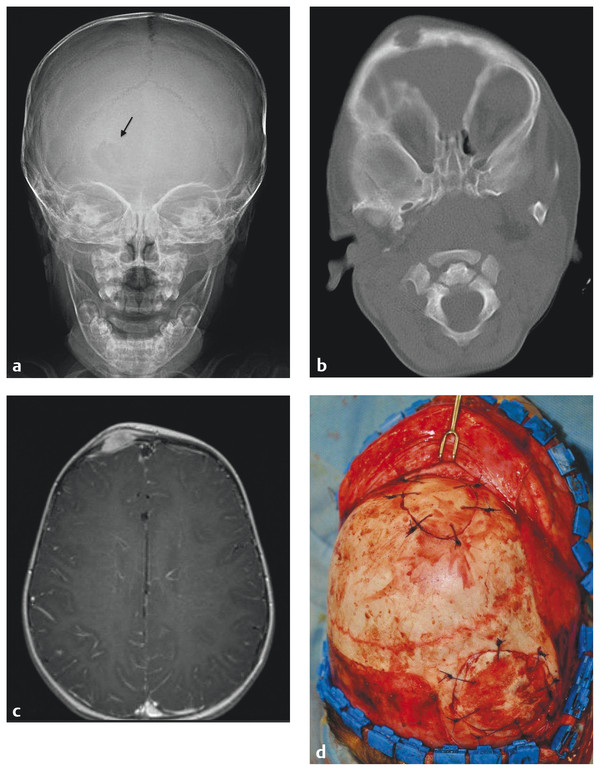

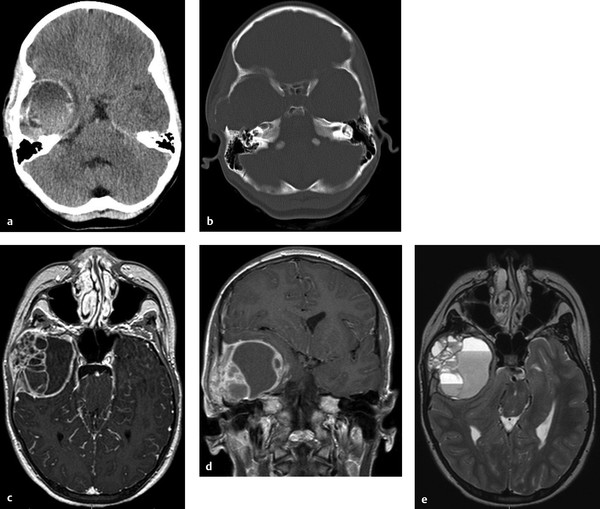

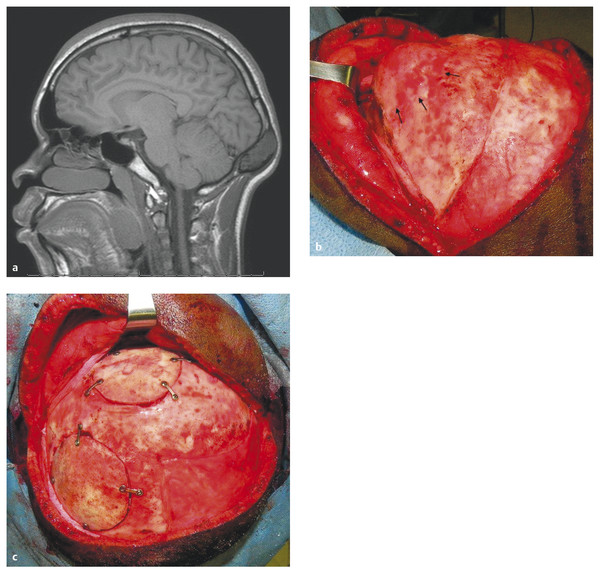

Scalp and Skull Neoplasms Children are frequently evaluated by neurosurgeons and other medical professionals for bumps on the head, but in reality neoplasms of the scalp and skull are relatively rare. In the pediatric population, tumors in this location comprise a diverse array of pathologies quite different from those seen in adults. Pediatricians, dermatologists, plastic surgeons, general surgeons, and otolaryngologists, as well as neurosurgeons, commonly evaluate children with scalp or skull masses. Therefore, clinical experience with these relatively rare lesions is limited in any given practice. The published medical literature reflects this, consisting mostly of case reports, which tend to concentrate on atypical presentations and small case series that are limited by patient preselection.1 Standardized protocols for the evaluation and treatment of children with scalp and skull tumors are lacking.2 Pediatric neurosurgeons are uniquely equipped to treat masses of the scalp and skull. Experience gained with modern techniques of craniofacial surgery charges the surgeon to consider the aesthetics of reconstruction as well as the efficacy of resection in the treatment of these lesions. Knowledge of the natural histories of specific neoplasms of this region, as well as familiarity with current adjuvant treatment regimens, will assist the neurosurgeon in planning both the resective and the reconstructive procedures. The majority of “lumps on the head” called to medical attention are not neoplastic. Congenital, posttraumatic, and inflammatory lesions frequently present as masses of the calvaria. An extremely wide range of pathologies appears in this location. General reviews of surgically treated scalp and skull masses in children show that about one-half are dermoid cysts.3–6 The remaining diagnoses consist of a wide variety of dissimilar lesions (▶ Table 32.1). The diagnosis is often obvious on physical examination; at other times, radiographic or histologic examination is necessary. Patients referred for evaluation of a scalp “lesion” or “mass” sometimes have an atypical form of an otherwise easily recognizable diagnosis, such as a meningoencephalocele. Congenital lesions are discussed in other chapters of this book and are included here for completeness only. Entities such as Langerhans cell histiocytosis, aneurysmal bone cyst, and fibrous dysplasia may not be truly neoplastic, but they share presentation and treatment patterns with neoplasms and thus are included in this chapter. Benign Malignant The presenting signs and symptoms of various scalp and skull lesions in children are quite similar, regardless of the primary pathology. The most common complaint is a visible or palpable mass. Congenital lesions may be noticed at birth by the examining physician or the parents. Birth-related swelling of the scalp may obscure a congenital lesion or cephalohematoma that will later become obvious. Newborns and infants with high-flow vascular malformations may have signs of high-output heart failure, including failure to thrive and cardiac murmurs. Some lesions are painful or tender to palpation. In preverbal children, pain may be expressed as irritability or failure to thrive. Careful neurologic examination is important, but newborns and infants may harbor surprisingly large intracranial masses and still exhibit a neurologic examination findings appropriate for their chronological age. Head circumference remains one of the most valuable measurements in the assessment of young children. Abnormal tufts of hair, discoloration of the scalp, and palpable skull defects may all present for neurosurgical evaluation at various ages. In older children, it is important to determine whether the lesion has changed in size or character recently. Not uncommonly, patients are referred by a general pediatric surgeon or dermatologist after lesions previously thought to be confined to the scalp have been found to extend through the calvaria.7 Most children referred to a neurosurgeon for the evaluation of a scalp or skull mass undergo imaging with computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance (MR) imaging. Ultrasound, however, is frequently used as a screening examination in newborns.8 Indeed, some form of neuroimaging is recommended for all but the most obvious of extracranial masses. Up to one-third of patients evaluated for a solitary nontraumatic lump on the head have some degree of intracranial extension.3,5 Occasionally, a predominantly intracranial process, such as a subdural empyema or even a brain tumor, may present with scalp swelling, especially in infants.3 Midline or pedunculated scalp masses should be evaluated with MR imaging to assess the degree of intracranial extension and any relation to the dural sinuses. For smaller scalp lesions, the abnormal area should be marked and called to the attention of the radiologist before scanning. MR imaging is generally preferable to CT for evaluating soft tissue masses and the diploic space of the skull. CT is superior for bony masses. The two imaging modalities, however, are frequently complementary (▶ Fig. 32.1a,b and ▶ Fig. 32.2).8 Many skull and scalp lesions are not well visualized on routine axial CT. Vertex skull lesions are obscured on axial images tangential to the lesion, so direct coronal or thin-section cuts with three-dimensional reconstruction are necessary for improved visualization. CT protocols should be specific for children to limit the radiation dose.9 Radionuclide bone scans should be reserved for lesions whose imaging characteristics are suggestive of possible multifocal pathology (e.g., Langerhans cell histiocytosis, Ewing sarcoma). Fig. 32.1 Skull dermoid. This young adult presented with a history of a lump on the back of her head for as long as she could remember. (a) Computed tomography demonstrates a full-thickness skull defect. (b) T1-weighted magnetic resonance (MR) imaging with contrast shows a large nonenhancing occipital mass hypointense to normal brain. (c) Diffusion-weighted MR imaging reveals restricted diffusion, consistent with a dermoid cyst. Fig. 32.2 Langerhans cell histiocytosis. This 18-month-old girl presented with swelling over the left side of the forehead. (a) Skull X-ray shows a lytic lesion with irregular but not sclerotic margins. (b) Computed tomography with bone window. (c) Axial T1-weighted magnetic resonance imaging with contrast shows marked enhancement. The lesion failed to resolve over 6 months and was completely resected. Pathology was Langerhans cell histiocytosis. (d) At the time of resection, primary reconstruction with split-thickness autologous cranial bone was performed. In children with scalp or skull tumors, surgery is indicated for the decompression of neural structures, curative or palliative resection, correction of disfiguring deformities, relief of pain, or biopsy of an unknown lesion. Given the low complication rate of craniotomy for the resection of skull lesions, total excision is generally performed rather than biopsy.2 It is not the intent of this chapter to describe specific surgical techniques, but rather to provide an overall framework for approaching the surgical management of these patients. All resective procedures should be planned in anticipation of a reconstructive procedure. It is the authors’ belief that the psychosocial effects of a cranial defect or a cosmetically disfiguring scar on a developing child, as well as the attitudes of others toward the child, should never be minimized. In many cases, the defect left by the resection of a skull tumor may be repaired primarily with a split-thickness bone graft taken from adjacent cranium. Accordingly, the scalp incision should be designed to allow maximum vascularity as well as access to potential donor craniotomy sites (▶ Fig. 32.3d and ▶ Fig. 32.4c). Despite its length, the standard coronal scalp incision is frequently the best choice. In situations in which poor wound or graft healing is anticipated (e.g., when radiation or chemotherapy is indicated), the reconstruction should be delayed until healing conditions are optimized. This may help avoid the loss of both donor and recipient grafts due to poor wound healing and/or infection. The need for intradural exploration is usually apparent from the preoperative imaging studies. Although most scalp or skull tumors do not demonstrate intradural extension, congenital lesions such as dermoid sinuses frequently have a definite connection to the underlying brain that must be appreciated. Failure to completely excise a dermal tract may allow growth of the residual intracranial component or result in delayed infection.10 Missed intracranial extension11 and postoperative adhesion of the brain to overlying dura12 have been reported to cause focal neurologic symptoms analogous to spinal cord “tethering.” Thus, intradural exploration should be performed when transdural extension is apparent. The presence of dural enhancement does not always necessitate opening of the dura. Many full-thickness skull lesions incite an inflammatory response in the dura, and neuroimaging reveals a “tail” of dural enhancement (▶ Fig. 32.3c). At the time of surgery, the tumor is often peeled off the outer dural layer, leaving the inner intact. Fig. 32.3 Aneurysmal bone cyst. This 12-year-old girl presented with a nontender firm mass in the right temple. (a,b) Computed tomography shows calcification surrounding the lesion; bone windows show a thin shell of intact bone externally. (c,d) Axial and coronal T1-weighted images with contrast reveal an enhancing soft tissue portion of the tumor. (e) Axial T2-weighted image shows typical fluid–fluid levels of nonclotted blood. Congenital lesions of the scalp are quite common, but actual neoplasms of the scalp are rare in children. Typical melanocytic nevi are common on the scalp.13 They are usually acquired, and although they may change with time, they rarely become suspicious for malignancy during childhood.14 Congenital melanotic nevi, on the other hand, are less common but require closer scrutiny for potential malignant transformation.15 Giant congenital melanotic nevi, sometimes called congenital hairy nevi, may occur anywhere on the skin, including the scalp. They are particularly distressing for families because of their conspicuous appearance. When these lesions involve the scalp or overlie the dorsal spine, abnormal collections of melanocytes may be observed in the underlying brain and meninges.16 The potential for intracranial or intraspinal proliferation in these situations is unknown. Congenital melanocytic nevi may be further classified as “compound” when the lesions involve both the dermis and epidermis. These nevi may give rise to basal cell carcinoma or malignant melanoma.17 Another type of congenital nevus requires special attention because of its known potential for malignant degeneration. Nevus sebaceus is a congenital hamartoma primarily of the sebaceous glands that may undergo transformation to basal cell carcinoma or other, more benign skin tumors.18–20 It appears as a hairless, slightly raised, pink or tan area, usually on the scalp but at times on the face or elsewhere. Traditionally, resection of these lesions has been recommended both for cosmetic reasons and to decrease the risk for future malignancy.17,18,21 The risk for malignant transformation may, however, be less than previously suspected, and therefore the timing of resection can be flexible.22 In large lesions, staged resection may be required, and scalp tissue expansion may be necessary for reconstruction after resection.21 In practice, dermatologists and plastic surgeons usually treat superficial lesions confined to the dermis; it is not until subgaleal or cranial involvement is apparent that neurosurgical consultation is obtained. The following conditions, although not necessarily neoplastic, are frequently encountered by pediatric neurosurgeons. Subcutaneous nodules of the scalp are common in children. Most do not extend intracranially.23 Lesions of the midline, painful lesions, or masses that on palpation are found to be fixed to the skull may require further neurosurgical evaluation. Scalp nodules result from numerous processes. In children especially, enlarged lymph nodes may present as scalp nodules, particularly in the postauricular region. Lymphadenopathy appears as firm, rubbery, mobile nodules, which may be tender. There is frequently a history of upper respiratory infection, and the lymphadenopathy is self-limited. After trauma, it is not uncommon in children to notice very firm nodules fixed to the skull, with or without skull fracture. These periosteal reactions should also resolve spontaneously. Scalp nodules associated with a tuft of abnormal hair frequently have a stalk, which may penetrate the skull to a variable extent. Although they are often assumed to represent a dermal sinus tract, these lesions may actually prove to be heterotopic neural nodules.24 These malformations are most likely part of a continuum of developmental pathology that includes atretic meningocele, cephalocele, and encephalocele, as well as dermal sinus tracts. The location is usually midline or para-midline in the parieto-occipital regions. Despite an underlying bony defect, no intracranial pathology is usually identified apart from a persistent falcine sinus.24 As a practical matter, knowledge of the histology in this clinical setting may differentiate heterotopic neural nodules from dermal sinus tracts, thus decreasing concern regarding the need for intradural exploration and continued observation. Neurofibromas of the scalp may accompany neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF-1) and to a lesser extent neurofibromatosis type 2 (NF-2).25 With an incidence of 1 in 3,000 live births, NF-l is a commonly observed condition in pediatric neurosurgical practice.26 In a patient with NF-1 or NF-2, the discovery of painless, subcutaneous nodules of the scalp does not usually present a diagnostic problem. Occasionally, however, a nodule may be found in the absence of known neurofibromatosis. Characteristic cutaneous markings such as café au lait spots and axillary freckling should be sought, although they may not yet be present in young children. Biopsy of a lesion that shows neurofibroma, although not usually essential, will prompt consideration of the diagnosis of neurofibromatosis. Resection of neurofibromas of the scalp may be indicated when lesions are painful (e.g., in proximity to the occipital nerve) or disfiguring. Biopsy or resection should be considered in neurofibromas that have rapidly enlarged because malignant degeneration is possible. Plexiform and diffuse neurofibromas may present as disfiguring masses in the scalp and face.27 Because of the diffuse nature of these lesions, complete resection is often impossible. When indicated, subtotal debulking may be performed for large disfiguring lesions or for airway protection. Multiple painless subcutaneous nodules of the scalp may result from an inflammatory process of unknown origin known generically as necrobiosis. Necrobiotic granulomas of the scalp are described under many titles, including rheumatoid nodules, benign rheumatoid nodules, pseudo-rheumatoid nodules, subcutaneous granuloma annulare, xanthogranulomas, and subcutaneous palisading granulomas of the scalp.28–30 Necrosis and degeneration of the dermal collagen are the predominant histologic features, with surrounding histiocytes and epithelioid and multinucleated cells.30 In contrast to true rheumatoid nodules associated with rheumatoid arthritis, these granulomas involve the scalp and pretibial subcutaneous tissue and are not found near the joints. Progression to clinical rheumatoid arthritis does not usually occur.29 The lesions have a predilection for the occipital and frontal regions of the scalp and usually resolve spontaneously. In general, biopsy is not indicated in typically appearing lesions.28,29 Necrobiotic xanthogranuloma may be associated with a systemic disease such as multiple myeloma. A single case with dura-based intracranial lesions has been reported in an adult.31 Fibrodysplasia ossificans progressiva is a rare genetic inflammatory disorder that commonly presents with scalp nodules in infancy.32 The disease is characterized by progressive heterotopic calcification of the soft tissues, which may be stimulated by trauma or surgery. Thus, biopsy or excision may be contraindicated.33 Patients with fibrodysplasia ossificans progressiva nearly always have a characteristic deformity of the great toes, and a definitive diagnosis can obtained by genetic testing.34 When surgery is indicated, specific anesthetic and perioperative considerations are recommended.35 Despite the benign nature of the majority of scalp nodules in children, the potential for the development of malignant lesions that require aggressive treatment should not be overlooked. Essentially any pathology that can affect the skin can involve the scalp. The diversity of pathologic conditions affecting the scalp is beyond the scope of this chapter, but as neurosurgeons we remain aware of the ability of the hair-bearing scalp to conceal pathologic lesions. A variety of benign proliferative disorders of mesenchymal tissue occur in infancy and may result in masses involving the scalp, skull, and occasionally the dura. These lesions have variable histologic appearances and generally have excellent long-term prognoses despite initial periods of alarmingly rapid growth. Biopsy and excision are generally performed for diagnosis and decompression. Definitive diagnosis depends on the histopathologic features, including the results of immunohistochemical studies.36 Infantile myofibromatosis is a mesenchymal proliferative disorder resulting in fibrous tumors of the skin, subcutaneous tissue, muscle, bone, and viscera. Sixty percent of lesions are present at birth and 88% appear by 2 years, making this the most common fibrous tumor of infancy.37 It may occur as a solitary tumor (myofibroma) or as multiple tumors (myofibromatosis). Solitary myofibromas often occur in the head and neck and may involve the skull.38–43 Some lesions appear to arise from the dura and result in a significant intracranial mass effect, although the brain and arachnoid are not invaded.39 Interestingly, the literature contains multiple reports of the spontaneous regression of infantile myofibromas, many of which reportedly occurred after biopsy.44–48 The reliability and time course of possible regression have not yet been defined, so that surgical excision is generally undertaken. If at operation dural invasion is observed, dural resection may be required.39,40 After complete resection, recurrence is rare, and adjuvant treatment is not indicated except in the case of multiple lesions involving the viscera.45 The histology of infantile myofibromatosis is characterized by two populations of cells: myoid spindle cells and perivascular cells comparable to hemangiopericytoma cells.40,41 There are rare reports of intracerebral myofibromas, usually occurring in patients with multiple lesions.48–50 It is postulated that these rare intracerebral tumors in the setting of infantile myofibromatosis may derive from the perivascular population of cells.48–50 This finding is consistent with the concept of a spectrum of infantile myofibroblastic lesions consisting of infantile myofibromatosis, infantile hemangiopericytoma, and possibly congenital infantile fibrosarcoma.51,52 Cranial fasciitis of childhood (CFC) is a relatively rare, benign scalp mass consisting of an abnormal proliferation of spindle cell fibroblasts in a myxoid stroma.36 Initially described in 1980, CFC is now considered a subset of the more common nodular fasciitis, distinguished—as its name indicates—by a cranial location and childhood presentation.53 CFC usually presents by 2 years of age as a firm, rubbery, nontender mass firmly attached to the skull, most commonly in the temporal region. The lesion is presumed to arise from the deep fascia or periosteum. These masses may grow rapidly and to alarming dimensions. Occasionally, the lesion grows predominantly intracranially, and although usually dura-based, it may rarely be purely intraparenchymal.54 CT generally reveals an enhancing osteolytic lesion with sclerotic edges. MR imaging also shows enhancement, but with a central nonenhancing component. The enhancing region is presumed to represent the fibrous component and the nonenhancing region the myxoid matrix.55 The etiology of CFC is unknown, but it may have a reactive component. Up to 15% of cases are associated with trauma.56–59 Other cases have been reported after radiation therapy60 and at sites of prior craniotomy.61 Recently, a subset of CFC has been found to have molecular similarities to desmoid fibromatosis and Gardner fibroma.62 Although spontaneous regression of CFC has been described, the reliability and time course remain unknown.63,64 Therefore, surgical resection of CFC is generally indicated for histologic diagnosis and relief of mass effect. Dural resection is usually unnecessary except in cases with a large intracranial extension.54 Bone invasion should be treated with excision or curettage. Despite an appearance alarmingly suggestive of malignancy, these lesions usually do not recur, and even incompletely resected lesions may regress over time.58,59,65–67 Intralesional steroid injection has recently been reported to be effective in a single child with multiple small CFC lesions without skull erosion.68 For lesions that are neither disfiguring nor of neurologic concern, this may be a acceptable option. Desmoplastic fibroma is a benign tumor arising from bone and characterized by abundant collagen formation. It generally occurs in adults but has been reported in the skulls of infants and children.69,70 Radiographically, it appears as a osteolytic lesion, and although histologically benign, it can be locally aggressive. Complete surgical resection is recommended when possible because incomplete resection may result in local recurrence, and unlike the other fibrous lesions mentioned previously, it has not been observed to undergo spontaneous regression.69,70 Failure of closure of the cranial neural tube results in a spectrum of anomalies ranging from massive encephaloceles to small skull defects through which the cranial meninges herniate without underlying cerebral abnormality. Small midline lesions, usually in the occipital region, are frequently referred to as atretic cephaloceles and are commonly seen in pediatric neurosurgical practice.1 The lesions are soft and compressible, and they may increase in size with Valsalva maneuvers. The overlying skin is frequently thin, hairless, and discolored. Neural elements may be present within the cavity of the lesion with variable or no connection to the underlying brain. As noted in the preceding section, these ectopic collections of neural cells may present as scalp nodules, as well.24 There are frequently associated structural anomalies of the brain seen on MR imaging.1,24 Aplasia cutis congenita is a full-thickness skin defect that frequently involves the scalp. Lesions of variable size usually occur in the midline vertex.71 In 20% of cases, there is also a defect of the underlying skull.72 In severe cases, the dura may also be deficient, and the child may have a large area of exposed brain. Initial efforts are aimed at the prevention of infection, with timely coverage of the defect. Although these lesions are known to heal with dressing changes, staged procedures may be necessary with tissue expansion and skull reconstruction. Vascular lesions of the scalp are common in children, occurring in up to 75% of all newborns.73The most common type appears as pink to red macular lesions over the forehead, face, or nuchal regions, and it usually fades completely over the first year or two of life. Some cutaneous vascular lesions actually progress with age. Cutaneous hemangiomas and cavernous malformations occur predominantly in the head and neck in newborns. They typically progress during the first year of life with spontaneous, often remarkable, involution thereafter. So-called port-wine stains are dermal regions containing abnormal blood vessels, usually capillaries and venules within the superficial vascular plexus.73 Port-wine stains may become increasingly conspicuous with progressive deformity of the soft tissues and occasionally the underlying bone. This process appears to result from progressive ectasia of the involved vessels rather than vessel proliferation. A deficiency of normal sympathetic innervation of the involved vessels may be causative.74 From a neurosurgical point of view, port-wine stains of the scalp and face may be markers of underlying cerebral involvement. Five percent of patients with port-wine stains have Sturge-Weber syndrome, with abnormal pial vasculature of the ipsilateral cerebral cortex, seizures, and varying degrees of cognitive impairment.73 Treatment of the cutaneous lesions is usually by argon or tunable dye laser irradiation and is dependent on cosmetic and psychological concerns in young children.73 Fistulous arteriovenous communications may occur in the scalp and appear as pulsatile, compressible masses or with high-output heart failure in infants. These scalp arteriovenous malformations (AVMs) are frequently referred to as cirsoid aneurysms of the scalp.75 Most scalp AVMs, especially in children, appear to be congenital; however, up to one-third may be acquired after trauma.76 In infants, the lesions may enlarge, thus consuming an increasing proportion of the cardiac output as well as creating marked venous dilatation throughout the scalp and face. Contrast CT may show enhancement of the subgaleal scalp, and MR imaging with MR angiography may further demonstrate the malformation, but catheter angiography is necessary to delineate the vascular anatomy clearly. CT angiography in children should be carefully considered because of the radiation exposure. Arterial feeding and venous draining vessels are predominantly extracranial; however, a small contribution may be demonstrated from “parasitized” intracranial vessels with compression of the extracranial arterial supply.76 The direct surgical treatment of AVMs of the scalp may be exasperating, with significant blood loss intraoperatively and an unexpectedly high recurrence rate postoperatively.76 Modern endovascular techniques of either direct puncture or transarterial embolization with a variety of thrombogenic agents can significantly reduce blood flow or even obliterate these malformations.75–79 Surgery is often required to resect residual fistulas or to remove the mass of embolic material.75,78 Apart from blood loss, the most significant surgical complication is scalp necrosis.76 Care must be taken not to carry the epigaleal dissection into the hair follicles of the scalp. The scalp incision should be planned based on the anatomy of the AVM as well as on the possible need for scalp flap rotation. In contrast to scalp AVMs, the vascular lesion referred to as sinus pericranii is a relatively slow-flow anastomosis between extracranial and intracranial veins, usually involving the superior sagittal sinus.80 The lesion presents as a painless swelling of the scalp, usually in the midline or para-midline. The lesion is compressible, deflates with head elevation, and refills with Valsalva maneuver or with the head in a dependent position. Like scalp AVMs, most sinus pericranii lesions appear to be congenital, although some may be posttraumatic. Sinus pericranii presents predominantly in childhood but may come to medical attention during adulthood, especially when acquired after trauma. In most cases, sinus pericranii can be diagnosed clinically. Skull X-rays show only the skull defect, which may be quite small. Contrast CT and conventional angiography frequently fail to adequately illustrate the lesions. Direct injection of contrast into the blood-filled subgaleal mass may be required if radiographic confirmation is desired.80,81 Sinus pericranii is usually adequately treated by direct surgical obliteration without preoperative embolization. The decision to operate is based on symptoms, cosmetic concerns, and fear of bleeding from the lesion, the perceived risk of which is usually greater than the actuality.80 A wide variety of bone lesions present in childhood, including developmental, inflammatory, traumatic, and both benign and malignant neoplastic pathologies. Mostly, these lesions occur in the extracalvarial skeleton, with only sporadic appearances in the skull. The list of lesions is extensive, and only those pathologies with significant presence in the skull are reviewed here. The interested reader is referred to the more general reviews of bone tumors in children.82,83 Dermoid and epidermoid cysts are the most common lesion of the scalp and calvaria encountered by pediatric neurosurgeons; they account for about half of masses in this region.3,4 Dermoid cysts and dermal tracts are more likely to present in the scalp and skull of young children, whereas epidermoids tend to occur intracranially in older children and young adults. These congenital lesions are thought to result from varying degrees of failure of disjunction of neuroectoderm from cutaneous ectoderm during closure of the neural tube. Dermoid cysts contain elements of full-thickness skin, including epithelium, hair structures, and sebaceous glands. There may or may not be a visible sinus or pit overlying the lesion. The lesions are usually first observed by the parents in the newborn period. Occasionally, a small cyst may enlarge or become infected, prompting evaluation. Growth occurs as epithelial cells desquamate and break down, producing an accumulation of keratin and cholesterol. The most common location in children is at the anterior fontanel, where there is rarely dural penetration.84 Many experienced surgeons forego neuroimaging of lesions in this location except in unusual situations. Dermoid cysts also occur along sutures, usually without dural penetration. However, dermoid cysts of the occipital midline often have some degree of intracranial involvement, and MR imaging is recommended.10 MR images should be obtained with diffusion weighting, which reveals restricted diffusion (▶ Fig. 32.1c). Even when neuroimages fail to show intracranial penetration, exploration frequently shows a slender tract extending through the cranial bone and attaching to the dura. In these cases, the tract may simply be coagulated and divided, and intradural exploration is usually not indicated because of the relationship to midline dural venous sinuses.10 Langerhans cell histiocytosis (LCH) is an abnormal proliferation of cells similar to Langerhans cells normally found in skin and lymph nodes.85 Although the proliferations are clonal, current thinking regarding etiology is shifting from neoplasia to defective immune regulation.86 An inciting stimulus is as yet unidentified. LCH has an incidence of 8 to 9 per million per year in children.86 In the past, depending upon the extent of involvement, LCH was variously known as eosinophilic granuloma, Hand-Schüller-Christian disease, or Letterer-Siwe syndrome. In the aggregate, these forms were also known as histiocytosis X. Langerhans cell histiocytosis is the current preferred terminology. LCH usually appears before puberty, typically in children 4 to 12 years of age.87–89 The clinical presentation of LCH is extremely variable. Most bones and virtually any organ, including the brain, may be affected.88,89 Risk is based on classification into single-system LCH and multisystem LCH (Minkov). Single-system disease may be uni- or multifocal. The most frequent site of involvement is the skull; the child typically presents with a painful mass and often with a history of recent growth or antecedent trauma.90 LCH of the skull base also occurs and may present more of a diagnostic dilemma. Temporal bone lesions can present with symptoms resembling those of otitis media or mastoiditis.91 Lesions of the clivus may present with abducens nerve palsies, which in children may appear as abnormal head position.92 Dural sinus thrombosis caused by compression from an occipital LCH lesion may lead to symptoms of pseudotumor cerebri.93 Skull radiographs show a radiolucent, “punched-out” lesion without sclerotic margins (▶ Fig. 32.3a). CT of the skull defines intracranial extension, which is usually minimal (▶ Fig. 32.3b).94 The lesion is characterized by low intensity on T1-weighted MR images and high intensity on T2-weighted MR images.95 LCH lesions enhance markedly but inhomogeneously.95 A tail of dural enhancement and enhancing reactive change in the overlying galea and muscle is a common finding not indicating invasion (▶ Fig. 32.3c).95,96 Although unifocal involvement of the skull is common, it is important to rule out involvement at other sites. Multifocal bone involvement occurs in 28% of children and 20% of adults.87 Radiographic skeletal survey and radionuclide bone scan appear to be complementary for the evaluation of polyostotic disease.97–99 Bone scan better detects lesions in the ribs and vertebrae, and skeletal X-rays are more accurate for the skull and long bones.97 Cerebral involvement is often heralded by diabetes insipidus, and hypothalamic lesions may be seen on MR imaging.99,100 The treatment of unifocal LCH of the skull usually consists of complete, full-thickness excision of the lesion.101–103 There is rarely underlying dural penetration. Reconstruction of the defect with autologous split-thickness cranial bone from adjacent skull is easily performed at the time of primary resection. Biopsy and curettage have been recommended, but without clean bone margins, the healing of a bone graft may be impaired. Complete resection is associated with a low recurrence rate, and adjuvant treatment is not usually indicated.101–103 Although surgical treatment is generally undertaken, spontaneous resolution of skull lesions has also been documented.104 Thus, some authors recommend a period of observation to see if spontaneous resolution occurs.87,89,104 Enthusiasm for conservative management may be tempered by the possibility of hemorrhagic complications arising from cranial LCH lesions.105,106 It is also unclear if persistent lesions predispose to disseminated disease.107,108 Recently, LCH in the orbit, mastoid, or temporal skull region has been classified as “central nervous system risk” because of an increased frequency for the development of diabetes insipidus and other endocrine abnormalities or parenchymal brain lesions.109 Surgery for LCH of the long bones is often avoided because of the risk for instability. Thus, there is more experience with the nonsurgical management of lesions in these locations. Success has been demonstrated for local steroid injection108 and for a wide variety of systemic therapies and low-dose radiation therapy.86 Disseminated or multisystem involvement, patient age younger than 2 years at diagnosis, and hepatosplenomegaly or thrombocytopenia are poor prognostic factors.87,89 Recurrent or progressive disease may be treated with low-dose radiation or chemotherapy. Stereotactic radiotherapy may prove beneficial for focal skull base lesions.50 Chemotherapeutic regimens for high-risk patients are actively being developed.109,110 In keeping with the unknown etiology of LCH, the natural history of the disease is also not clearly understood; likewise, the influence of current therapeutic modalities is not well defined. Surgery, radiation, and chemotherapy have not been shown conclusively to affect outcome. The reported occurrence of new bone lesions in children is 22%, and the local recurrence rate after treatment is 6%.87 Recurrence is usually seen within 2 years of the diagnosis; in adults, recurrence may be years later.87 It seems reasonable to follow children with LCH of the skull for at least 5 years with X-rays, bone scans, or both. Fortunately, recurrent or new bone lesions without extraskeletal involvement are not associated with a worsened prognosis.87,109,111 Aneurysmal bone cysts (ABCs) are tumorlike expansions of the diploic space that distort and attenuate the overlying cortical bone (▶ Fig. 32.42). The cystic lesions themselves are filled with blood and lined by connective tissue with giant cells and trabecular bone.112 About 80% of these lesions come to medical attention before the end of the second decade of life.112,113 Only 2% of ABCs arise in the bones of the skull.114 Up to 30% may involve the spine (Novais). Most experience with ABCs has been obtained with lesions in the long bones. Of skull lesions, about two-thirds are confined to the maxilla or mandible.114 Presentation in the skull usually involves a painful expanding mass.115 Cranial neuropathies may be present if the lesion is in proximity to the cranial nerve foramina.116 These tumors may grow to considerable size, especially in infants, and may present with raised intracranial pressure117,118 Although the etiology of ABCs is not known, nearly one-third of the lesions in the long bones are considered “secondary” to other bone lesions, such as giant cell tumors and osteoblastomas.112,113 A similar association has been observed in ABCs of the skull67 with additional primary pathologies, including LCH and fibrous dysplasia.117–119 Thus, although the radiographic appearance of these lesions may be characteristic, a diligent pathologic search must be made for any accompanying lesion. ABCs have a distinctive radiographic appearance, with expansion but not destruction of the cortical bone and fluid–fluid levels within the cysts themselves (▶ Fig. 32.2e). Although they may expand intracranially, they do not penetrate dura. ABCs are vascular lesions, and direct operation in children is frequently associated with significant blood loss. Preoperative angiography is thus often indicated, with the consideration of embolization. Treatment is usually surgical, after embolization. Complete resection is the goal, followed by primary reconstruction. Curettage of residual abnormal bone along margins that are not safely resected is acceptable. However, in long bones, curettage alone is associated with a recurrence rate of up to 60%.113 For this reason, and considering the association of ABCs with other bone lesions, close postoperative radiographic surveillance is recommended. Residual or recurrent lesions usually respond to radiation therapy, with its inherent risks.113 Cryosurgery reduces rates of recurrence after primary surgery and offers an alternative to radiation therapy when recurrent disease is treated.113 However, application in the cranium has not yet been reported. In cases in which the risk of operative resection is considered too great, the direct injection of acrylic sclerosing agents has been reported to be effective.120 Fig. 32.4 Fibrous dysplasia. This 17-year-old young man presented with a long-standing occipital mass that had recently enlarged and became tender. (a) Sagittal T1-weighted magnetic resonance image showing isointense expansile calvarial lesion in the region of the inion. (b) Intraoperative photograph of lesion. (c) Intraoperative photograph showing reconstruction with split-thickness autologous cranial bone.

32.1 Differential Diagnosis

Etiology

Lesion

Congenital

Aplasia cutis congenita Dermoid cyst/dermal sinus tracts Atretic meningocele/meningocephalocele Nevus sebaceus

Neoplastic

Neurofibroma Osteoma, osteoid osteoma, osteoblastoma Fibrous dysplasia Ossifying fibroma Giant cell tumor Aneurysmal bone cyst Melanotic neuroectodermal tumor of infancy Neuroblastoma Lymphoma Ewing sarcoma Osteogenic sarcoma

Posttraumatic

Calcified cephalohematoma Growing skull fracture (leptomeningeal cyst)

Vascular

Hemangioma Sinus pericranii Arteriovenous fistula/cirsoid aneurysm

Inflammatory

Langerhans cell histiocytosis Lymphadenopathy Necrobiotic nodules (benign rheumatoid nodules/subcutaneous palisading granulomas) Myofibromatosis Cranial fasciitis Osteomyelitis

32.2 Clinical Presentation

32.3 Diagnostic Studies

32.4 Surgical Concepts

32.5 Lesions of the Scalp

32.5.1 Scalp Nodules

32.5.2 Mesenchymal Tumors

32.5.3 Scalp Defects

32.5.4 Vascular Lesions of the Scalp

32.5.5 Arteriovenous Malformations of the Scalp

32.5.6 Sinus Pericranii

32.6 Lesions of the Skull

32.6.1 Epidermoid and Dermoid Cysts

32.6.2 Langerhans Cell Histiocytosis

32.6.3 Aneurysmal Bone Cysts

Scalp and Skull Neoplasms

Only gold members can continue reading. Log In or Register to continue

Full access? Get Clinical Tree