Toyota Production System Seven Wastes. (©Virginia Mason Medical Center)

Examples of types of waste identified in lean methodology

Type of waste | Description | Examples in anesthesia and spine surgery |

|---|---|---|

Defect | Waste related to costs for inspection of defects in materials and processes, not meeting specifications | Medication errors |

Unplanned readmissions due to complications | ||

Overproduction | Producing something at the wrong time or in unnecessary amounts | Unused blood products |

Unused sterile equipment | ||

Waiting/time | Waiting for people or services to be delivered (people, processes or equipment are idle) | Waiting on laboratory results |

Waiting for operating room turnover | ||

Waiting for an available bed in PACU | ||

Transportation | Conveying, transferring, picking up, setting down, piling up, or otherwise moving unnecessary items | Poor layout in patient flow leading to multiple patient transfers |

Inventory | Supplies, material, or information exceeding what is required/needed | Unused sterile equipment |

Excessive stock in storerooms | ||

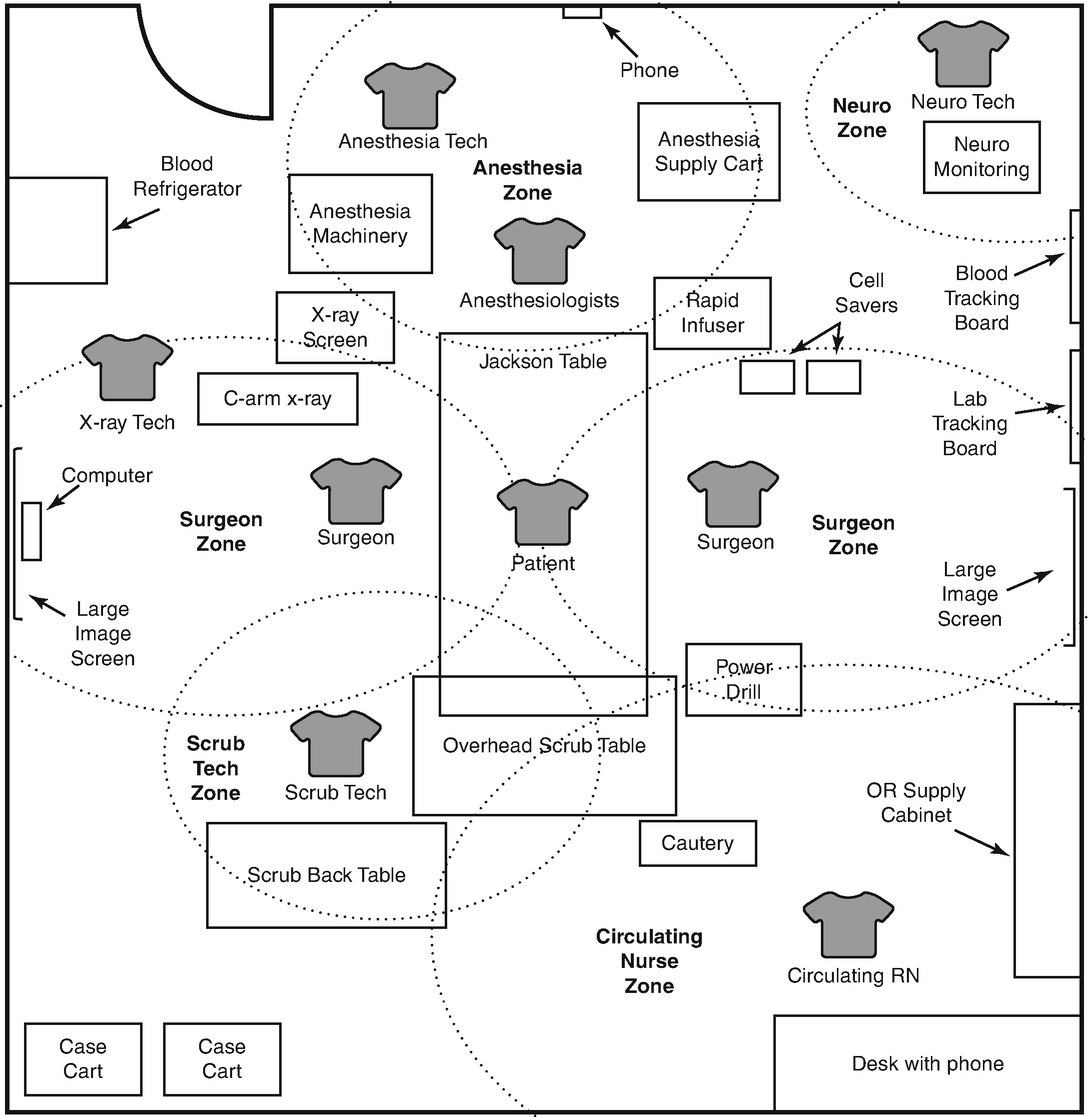

Motion | Unnecessary movement performed too quickly or slowly, which does not add value to a process | Less than optimal operating room design resulting in unnecessary movement |

Unknown location of a needed item | ||

Extra processing | Unnecessary processes and operations | Repeated collection of data, including laboratory testing, resulting in duplicate entries |

Preoperative

The Seattle Spine Team protocol is initiated once the patient with a diagnosis of Adult Spinal Deformity (ASD) is scheduled for a consultation at our tertiary referral surgical spine clinic. The first step in the treatment pathway entails gathering a standard set of full-length scoliosis films needed to evaluate the extent of spinopelvic malalignment as measured by sagittal and coronal balance, pelvic parameters, and Cobb angles of major and minor curves [12]. If symptoms of radiculopathy or neurogenic claudication are present on examination, Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) of the lumbar spine is added to rule out disc herniation or spinal stenosis. Dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry (DEXA) measurements from the femoral neck are also collected in advance of a multidisciplinary case review to aid in the discussion of patient’s risk for developing a non-union or Proximal Junction Kyphosis (PJK) following multilevel fusion for the correction of ASD [13–15]. Cohort studies have suggested that the risk of non-union and graft subsidence increases with a decreasing T-score [16], with similar findings reported by investigators analyzing the relationship between preoperative Vitamin D levels and postoperative outcomes following spine surgery [13–15]. Thus, we currently include femoral neck T-score measurements when assessing surgical appropriateness during patient’s preoperative evaluation and counseling.

In addition to the radiographic data, we collect a comprehensive medical history and conduct a thorough physical examination for all patients with significant medical comorbidities and those who are expected to undergo a procedure involving six or more levels of fusion or six or more hours of case duration. A comprehensive report summarizing the patient and including preoperative Body Mass Index (BMI), age, Hemoglobin A1c [17–19], tobacco use, mental health [20–29], opioid utilization, pulmonary [30] and cardiac function [31], and radiographic data is prepared for presentation to a live multidisciplinary team consisting of neurosurgeons, dedicated complex spine anesthesiologists, orthopedic surgeons, internists, physiatrists, mental health professionals, and nurses as part of a comprehensive strategy aimed at preoperative risk mitigation.

Treatment recommendation provided by this core team of specialists is case-specific and evidence-based when possible. We understand that not all medical decisions can be supported by clear scientific evidence, and therefore we will attempt to reach a consensus opinion that balances our understanding of the relevant literature with the expertise and experience of the members of the conference. We attempt to allow for an equal “vote” by all team members independent of specialty and, in cases of significant dispute, we will attempt to identify particular areas of contention that could be addressed with further evaluation, a second opinion visit with a surgical or non-surgical provider, or further discussion with the patient. Documented recommendations are communicated to the patient at a follow-up visit and may involve additional testing or lifestyle modifications. Recognizing functional limitations, patients with BMI exceeding 40 kg/m2 are counseled on potential lifestyle interventions and medical alternatives targeting weight loss, while patients with history of tobacco use and positive cotinine studies are offered various smoking cessation strategies well in advance of their scheduled surgery. The benefit of preoperative smoking cessation in patients undergoing surgery has been shown to correlate with the timing of the intervention, with greatest reduction in the rate of intra- and postoperative complications reported for patients whose smoking interventions were initiated at least 3 weeks before surgery [32, 33]. In our practice, two negative cotinine studies are required in patients with history of tobacco use with the second test scheduled at least 1 week prior to the schedule surgery. In the event of a positive test and after discussion with the patient, the surgical date will be rescheduled to allow for complete smoking cessation.

Results of non-surgical interventions and further diagnostic testing are re-presented on case-by-case basis at the monthly multidisciplinary conference. Upon consensus regarding surgical appropriateness, a tailored treatment plan is designed to provide optimal surgical correction while anticipating unavoidable patient-specific medical issues. For example, acute pain management of patients on active opioid replacement or agonist therapy prior to surgery due to history of addiction is provided by the dedicated Complex Spine Anesthesia Pain Service (APS). Faced with a complicated task of providing adequate pain relief in a patient population at a high risk of relapse [34], the APS team is essential to optimizing postoperative outcomes with a safe pain medication regimen.

Once cleared for surgery, a monthly educational class taught by a clinical nurse specialist offers another opportunity for patients and their caregivers to review surgical risks and procedure-related information. Administration of a health literacy questionnaire in the beginning of the class ensures that all learning styles and barriers to understanding are adequately addressed during both the class and following surgery. Previous studies have shown that patients who have limited comprehension of surgical risks are more like to be dissatisfied and file legal claims after surgery, while those who receive additional preoperative education report increased patient and family member satisfaction, fewer pain medication requests, and reduced length of hospital stay [35–38]. Since the clinical nurse specialist teaching the course is involved throughout the continuum of spine care, including in the preoperative multidisciplinary conference and postoperative outpatient care in the spine clinic, their experience facilitates ongoing communication with patients that can help clarify any points of misunderstanding or concern.

The final preoperative step is a preoperative clinic assessment by an anesthesiologist. This assessment is part of the standard work processes for any patient undergoing surgery at our institution, not only the complex spine patients, and the findings from this system review are used in standard OR work on the day of surgery.

Intraoperative

The intraoperative surgical plan will have been discussed and reviewed as part of the preoperative conference. During these discussions, the surgeons will review the rationale for the magnitude of the surgical procedure including the extent of fusion, the use of interbodies, the desired surgical goals, and the potential role for staging within the surgical procedure. The field of spine surgery is an ever-changing one, and we attempt to utilize current best practices in deciding upon the answers to the above questions. As discussed within the preoperative subsection, all patients will have a set of full-length standing scoliosis films and during the conference the type of deformity will be clearly identified. Our population is primarily an adult one, with a smaller subset of pediatric patients or adult patients with untreated adolescent curves, and so we will ensure that the surgical plan attempts to address issues of coronal and sagittal balance in addition to the more standard issues of central or foraminal stenosis that plague adult patients. Over the past decade, we have moved towards a greater use of lateral interbodies in the mid-lumbar levels or anterior interbodies at the lower lumbar levels to aid in lordosis restoration and eventual fusion. The decision for particular interbodies often guides the decision for staging of the surgical procedure. Our general algorithm is that any two surgical approaches can be performed within a single day, but if three distinct approaches are going to be utilized, then the operation will typically be staged over two separate days. In the earlier implementation of this protocol, the stages would be separated by 2–3 days to allow for some delayed resuscitation, but with greater experience of both the surgical and anesthesia teams, the two stages will typically be performed on sequential days. The anesthesia team typically will place a central line prior to any complex spine procedure with an expected blood loss approaching 1 L, which includes the majority of the scoliosis deformity procedures . In the event of a staged procedure we will aim to stack the interbody procedures on the first day to provide a large amount of the curve correction and indirect decompression. As these procedures are often performed through minimally invasive means or through smaller incisions that do not require extensive dissection, the central line is not placed on this first operative day but is instead placed after induction on the second day of surgery, thereby reducing the number of days that patients have an indwelling line. We understand that the data regarding surgical staging is conflicting [39–42], with some reports suggesting an increase in infection rates or total blood loss while other reports do not demonstrate such effects. In our experience, the potential advantage of completing an operative procedure involving three approaches within one operative setting are outweighed by the length of the surgical day, the fatigue of the operative team, the potential requirement upon substitute operating room personnel in the late afternoon or early evening hours, and the development of an intraoperative coagulopathy that appears to be time-related. This late coagulopathy can drive up the blood loos in later portions of the surgical procedure and further slow the operating team as they struggle to complete the procedure in an operative field that is partially obscured by ongoing bleeding. This staging decision is one that will have to be made by each individual surgical/anesthesia team, and we agree that others may place a lesser or greater reliance on the use of alternate approaches for the placement of interbodies that may lead to different decisions regarding the role for operative staging. We would hasten to add, however, that it has also been our experience that including the option for staging and not requiring it due to an easier-than-expected procedure is often far better received than the opposite, and therefore especially in the younger surgeon’s or newer teams’ career, such an option should be srongly considered.

The Seattle Spine Team Approach mandates the use of two surgeons for complex spine procedures. The logic behind this portion of the protocol arose from the airline industry’s use of pilot-copilot roles for all larger carrier airplanes. The medical community has recognized that there may be benefit to utilizng the learnings of other industries that have instruments of high complexity and which involve the direct care of human life [43]. Operator error is a potentially controllable source of poor outcome, and the presence of a surgical colleague may be able to reduce this risk. This colleague can aid not only the physical component of the surgical work, but can aid in decision-making during the procedure. In the case of a straightforward uncomplicated case, the mental load of surgery may be relatively minimal, but the field of complex spine surgery is often filled with less than ideal situations, including abnormal anatomy, unclear boundaries, or previous scar and the loss of standard landmarks. These difficult scenarios may be surmounted more easily with two proficient surgeons than one. The effect of the two-surgeon model has been studied in both adult and pediatric spine surgery [44–46], with most studies demonstrating an improvement in both operative time and total estimated blood loss and some describing a reduction in surgical complications. While the question may arise as to the need for two attending surgeons versus merely one attending and an experienced fellow, one study that broke down the surgical procedure into six individual steps noted a significant improvement in operative time in four of these steps when two attendings were used rather than an attending and fellow [46]. Our initial protocol called specifically for two attending surgeons, however with the greater experience of the surgical team and in the presence of a fellow with appropriate surgical skills, we allow for completion of a surgical case by an attending and fellow after discussion with the anesthesia team and other attending surgeons. More difficult procedures such as pedicle subtraction osteotomies, severe revision cases or more pronounced deformities are still performed by two attending surgeons, however. This requirement does have financial and scheduling ramifications, and it appears that the difficulty in implementing this portion of the protocol in other institutions is primarily related to these two factors, even as many surgeons agree with its benefits [47].

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree