Adapted from Gorchein A. Drug treatment in acute porphyria. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 1997;44:427–434.

OXYGEN DEPRIVATION

Perinatal Anoxia and Hypoxia

Whether it occurs in utero, during delivery, or in the neonatal period, significant anoxia can extensively damage the CNS and lead to neonatal seizures, which carry a risk for increased mortality. The pathophysiology, classification, diagnosis, evaluation, and treatment of neonatal seizures are covered in Chapter 35.

Adult Anoxia and Hypoxia

In adults, anoxic or hypoxic seizures are residuals of cardiac arrest, respiratory failure, anesthetic misfortune, carbon monoxide poisoning, or near-drowning. Precipitating cardiac sources typically are related to embolic stroke, 13% of which involve seizures (58) or hypoperfusion or hyperperfusion of the cerebral cortex (2). Approximately 0.5% of patients who have undergone coronary bypass surgery experience seizures without evidence of focal CNS injury (59). In patients with respiratory disorder, acute hypercapnia may lower seizure threshold, whereas chronic stable hypoxia and hypercapnia rarely cause seizures. Subacute bacterial endocarditis can lead to septic emboli and intracranial mycotic aneurysms, which can produce seizures either from focal ischemia or from subarachnoid hemorrhage. Syncopal myoclonus and convulsive syncope may result from transient hypoxia.

Subtle seizures may involve only minimal facial or axial movement (60), increasing the suspicion for nonconvulsive status epilepticus that typically signifies a poor prognosis (61,62). Myoclonic status epilepticus or generalized myoclonic seizures that occur repetitively for 30 minutes are usually refractory to medical treatment (63). Concern has been raised that myoclonic status epilepticus may produce progressive neurologic injury in comatose patients resuscitated from cardiac arrest (63). When postanoxic myoclonic status epilepticus is associated with cranial areflexia, eye opening at the onset of myoclonic jerks, and EEG patterns that include generalized bilateral independent epileptiform discharges or burst suppression pattern, the outlook for neurologic recovery is grim (64).

Treatment is directed mainly toward preventing the cascade of hypoxic injury. Barbiturate medication and reduction of cerebral metabolic requirements by continuous hypothermia may prevent the delayed worsening (65). Frequently, the seizures cease after 3 to 5 days. Phenobarbital 300 mg/day, clonazepam 8 to 12 mg/day in three divided doses, and 4-hydroxytryptophan 100 to 400 mg/day have been recommended (66), as has valproic acid (67). Levetiracetam 1000 to 3000 mg/day may also be useful for posthypoxic seizures and myoclonus with less sedating effects (68).

ALCOHOL

Generalized tonic–clonic seizures occur during the first 48 hours of withdrawal from alcohol in intoxicated patients and are most common 12 to 24 hours after binge drinking (69). Seizures that occur more than 6 days following abstinence should not be ascribed to withdrawal. Interictal EEG findings are usually normal. Partial seizures often result from CNS infection or cerebral cicatrix caused by remote head trauma. Recent occult head trauma, including subdural hematoma, should be considered in any alcoholic patient. Although the incidence of alcoholism in patients with seizures is not higher than in the general population, alcoholic individuals do have a higher incidence of seizures (70).

The treatment depends on associated conditions, but replacement of alcohol is generally not recommended. To prevent the development of Wernicke–Korsakoff syndrome, thiamine should be administered prior to IV glucose. Magnesium deficiency should be corrected, as reduced levels may interfere with the action of thiamine. Preferred treatment is with benzodiazepines or paraldehyde. In countries outside the United States where paraldehyde is available, it may be administered in doses of 0.1 to 0.2 mL/kg orally or rectally every 2 to 4 hours. Diazepam, lorazepam, clorazepate, and chlordiazepoxide in conventional dosages are equally useful (71).

INFECTIONS

Infection is associated with seizures, both directly via parenchymal invasion by the pathogen and indirectly via neurotoxins. Direct parenchymal infections may be bacterial, fungal, mycobacterial, viral, spirochetal, or parasitic. Neurodegenerative disorders, such as Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease and subacute sclerosing panencephalitis, can also result from CNS infection.

Meningitis

Patients with seizures, headache, or fever (even low grade) should undergo lumbar puncture once a mass lesion has been excluded. In the infant with diffuse, very high intracranial pressure, lumbar puncture should be delayed until antibiotics and pressure-reducing measures are initiated. The pathogenic cause of bacterial meningitis varies with age: In newborns, Escherichia coli and group B streptococcus are most common; in children 2 months to 12 years of age, Haemophilus influenzae, Streptococcus pneumoniae, and Neisseria meningitidis are usual; in children older than 12 years of age and in adults, S. pneumoniae and N. meningitidis are found most often; in adults older than 50 years of age, H. influenzae is increasingly being reported. In infants, geriatric patients, and the immunocompromised, Listeria monocytogenes must also be considered.

Encephalitis

The herpes simplex variety is the most common form of encephalitis associated with seizures (72). Fever, headache, and confusion are punctuated by both complex partial and generalized seizures secondary to the propensity of the virus to produce a hemorrhagic encephalitis involving the temporal lobe. Equine encephalitis, St. Louis encephalitis, and rabies also produce seizures.

Diazepam or lorazepam may be used for the acute control of seizures caused by meningitis or encephalitis. Recurrent seizures or the development of status epilepticus indicates the need for maintenance AED therapy.

Nonbacterial Chronic Meningitis

Lyme disease, a tick-borne spirochetosis, is associated with meningitis, encephalitis, and cranial or radicular neuropathies in up to 20% of patients. Seizures are not a prominent feature. Treatment consists of high-dose IV penicillin G in addition to AEDs (73).

Neurosyphilis is another spirochetal cause of seizures, which occasionally are the initial manifestation of syphilitic meningitis. In the early 20th century, 15% of patients with adult-onset seizures had underlying neurosyphilis. The incidence decreased dramatically over the years; however, the recent upsurge in primary syphilis among younger individuals is reflected in the report that seizures occur in approximately 25% of the patients with symptomatic neurosyphilis. The diagnosis rests on the demonstration of positive serologic findings and clinical symptoms, but the signs are not pathognomonic and often overlap with those of other diseases. IV penicillin remains the treatment of choice.

Sarcoidosis involves the CNS in approximately 5% to 15% of cases. Neurosarcoidosis should also be considered in patients with nonbacterial meningitis and seizures (74).

Opportunistic CNS Infections

Acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) is associated with several unique neurologic disorders, and seizures may play a major role when opportunistic infections or metabolic abnormalities, especially cerebral toxoplasmosis or cryptococcal meningitis, occur. Listeria monocytogenes should also be considered in immunocompromised patients. Metabolic abnormalities, particularly uremia and hypomagnesemia, predispose patients infected with the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) to seizures. New-onset epilepsia partialis continua as an early manifestation of progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy in patients with HIV-1 infection has been reported (75). CNS lymphoma in HIV-infected patients may also give rise to seizures.

Parasitic CNS Infections

In some areas, neurocysticercosis is the most commonly diagnosed cause of partial seizures. The adult pork tapeworm resides in the human small bowel after ingestion of infected meat. The oncospheres (hatched ova) penetrate the gut wall and develop into encysted larval forms, usually in the brain or skeletal muscle. Computed tomography (CT) scans reveal calcified lesions, cysts with little or no enhancement, and usually no sign of increased intracranial pressure. In the past, treatment involved the use of only praziquantel 50 mg/kg/day for 15 days or albendazole 15 mg/kg/day. However, while undergoing therapy, most patients had clinical exacerbations, including worsening seizures, attributed to inflammation with cyst expansion caused by the death of cysticerci. For this reason, treatment with the antihelminthic drug and steroids has been advocated. Antihelminthic agents by themselves do not change the course of neurocysticercosis or its associated epilepsy. A trial of antihelminthic agents combined with steroids or steroids alone showed comparable efficacy in terms of patients who were cyst free at 1 year or seizure free during follow-up (76).

Hydatid disease of the CNS (echinococcal infection) may result from exposure to dogs and sheep. Echinococcal cysts destroy bone, and a large proportion of such cysts are found in vertebrae. On CT scans, echinococcal brain cysts are fewer and larger than the cysts associated with cysticercosis. Treatment is usually surgical, largely because mebendazole and flubendazole have been associated with disease progression in up to 25% of patients. Nonetheless, adjuvant chemotherapy may be warranted in some cases (77).

Trichinosis may be encountered wherever undercooked trichina-infected pork is consumed. Complications of CNS migration include seizures, meningoencephalitis, and focal neurologic signs; eosinophilia is common during acute infection. Muscle biopsy may be necessary for diagnosis (72).

Cerebral malaria is similar to neurosyphilis, in that almost every neurologic sign and symptom has been attributed to the disorder. Diagnosis requires characteristic forms in the peripheral blood smear. Treatment depends on whether chloroquine resistance is present in the geographic region of infection.

Toxoplasmosis is a parasitic infection that affects adults, children, and infants. Use of immunosuppressive agents in patients with malignancies or transplants (see related sections later in this chapter), as well as recognition of AIDS, has emphasized the need to reconsider the neurologic sequelae of toxoplasmosis. Diagnosis may be elusive. Cerebrospinal fluid may reveal normal findings or mild pleocytosis (78). Serologic data may be difficult to interpret because encephalitis caused by Toxoplasma gondii may occur in patients who reactivate latent organisms and do not develop the serologic response of acute infection. CT scanning may reveal typical lesions. Therapy includes pyrimethamine and sulfadiazine or trisulfapyrimidines.

Cytomegalovirus retinitis, the most common ocular opportunistic infection in patients with AIDS (79), is increasingly being treated with a combination of foscarnet and ganciclovir. Foscarnet is also used to treat cytomegalovirus esophagitis associated with AIDS, but seizures have occurred with this agent, possibly as a result of changes in ionized calcium concentrations (80).

Systemic Infections

Systemic infection involving hypoxia (e.g., pneumonia) or metabolic changes may give rise to seizures. Through an indirect, poorly understood mechanism, seizures are prominent in two serious gastrointestinal (GI) infections: shigellosis and cholera. Ashkenazi et al. (81) demonstrated that the Shiga toxin is not essential for the development of the neurologic manifestations of shigellosis and that other toxic products may play a role.

Zvulunov et al. (82) examined 111 children who had convulsions with shigellosis and were followed for 3 to 18 years. No deaths or persistent motor deficits occurred. Only one child developed epilepsy by the age of 8 years; 15.7% of the children had recurrent febrile seizures. The convulsions associated with shigellosis have a favorable prognosis and do not necessitate long-term follow-up or treatment.

Most clinical manifestations of cholera are caused by fluid loss. Seizures, which are the most common CNS complication, occasionally occur both before and after treatment and may result from hypoglycemia or overcorrection of electrolyte abnormalities. The cornerstone of treatment, however, is fluid replacement. Up to 3% of body weight, or 30 mL/kg, should be administered during the first hour, followed by 7% for the next 5 to 6 hours. Lactated Ringer solution given IV with potassium chloride or isotonic saline and sodium lactate (in a 2:1 ratio) is used. Adjunctive treatment with a broad- spectrum antibiotic shortens the duration of diarrhea and hastens the excretion of Vibrio cholerae.

The seizures associated with shigellosis and cholera infection may share a common pathogenesis. Depletion of hepatic glycogen and resultant hypoglycemia are typically reported in children with these illnesses (83).

GASTROINTESTINAL DISEASE AND SEIZURES

In nontropical sprue, or celiac disease, damage to the small bowel by gluten-containing foods leads to chronic malabsorption. Approximately 10% of patients have significant neurologic manifestations, with the most frequent neurologic complication being seizures (reported in 1% to 10% of patients), which are often associated with bilateral occipital calcifications (84,85). Possible mechanisms include deficiencies of calcium, magnesium, and vitamins; genetic factors (86); and isolated CNS vasculitis (87). Malabsorption may be occult, and seizures may be the dominant feature. Strict gluten exclusion usually produces a rapid response.

Inflammatory bowel disease (ulcerative colitis and Crohn disease) is associated with a low incidence of focal or generalized seizures. Unsurprisingly, generalized seizures frequently accompany infection or dehydration. In approximately 50% of all patients with focal seizures, a vascular basis is suspected (88).

Whipple disease is a multisystem granulomatous disorder caused by Tropheryma whippelii (89). Approximately 10% of patients have dementia, ataxia, or oculomotor abnormalities; as many as 25% have seizures (90). Early treatment is important, as untreated patients with CNS involvement usually die within 12 months (91). Some patients develop cerebral manifestations after successful antibiotic treatment of GI symptoms (92). Although several agents that cross the blood–brain barrier, such as chloramphenicol and penicillin, have been suggested for treatment (93), a high incidence of CNS relapse led Keinath et al. (94) to recommend penicillin 1.2 million units and streptomycin 1.0 g/day for 10 to 14 days, followed by trimethoprim–sulfamethoxazole 1 double-strength tablet twice a day for 1 year. Treatment of the underlying disease may not prevent seizures; however, in which case, AEDs in a suspension or elixir are usually required because malabsorption is a significant problem (95).

Hepatic Encephalopathy

Wilson disease, acquired hepatocerebral degeneration, Reye syndrome, and fulminant hepatic failure, among other disorders, may lead to hepatic encephalopathy. Manifestations progress through four stages. Stage 1 is incipient encephalopathy. In stage 2, mental status deteriorates and asterixis develops. In stage 3, focal or generalized seizures may occur. Stage 4 is marked by coma and decerebrate posturing.

The incidence of seizures varies from 2% to 33% (96). Hypoglycemia complicating liver failure may be responsible for some seizures. Hyperammonemia is associated with seizures and may contribute to the encephalopathy of primary hyperammonemic disorders; treatments that reduce ammonia levels also ameliorate the encephalopathy (96). Therapy should be directed toward the etiology of the hepatic failure; levels of GI protein and lactulose must be reduced. Long-term use of AEDs is not usually required unless there is a known predisposition to seizures (e.g., previous cerebral injury). Little experience with the use of AEDs has actually been reported. Those AEDs with sedative effects may precipitate coma and are generally contraindicated. Valproic acid and its salt should be avoided. Nonhepatic metabolized AEDs including levetiracetam and gabapentin are more likely to be efficacious and avoid further exacerbation of the liver failure.

INTOXICATION AND DRUG-RELATED SEIZURES

This section is not to be used as a guide to the management of drug intoxication. Rather, it reviews specific instances of intoxication during which intractable seizures sometimes develop.

Prescription Medication–Induced Seizures

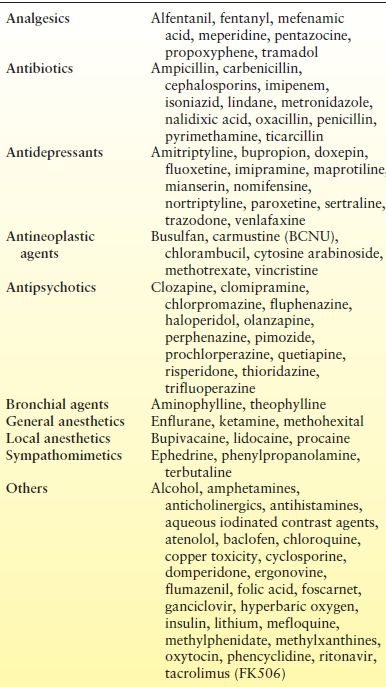

Many medications provoke seizures in both epileptic and nonepileptic patients (Table 36.2). Predisposing factors include family history of seizures, concurrent illness, and high-dose intrathecal and IV administration. The convulsions are usually generalized with or without focal features; status epilepticus may occur in up to 15% of patients (97). Because many medical conditions result from polypharmacy, drug- induced seizures may be more common in geriatric patients.

Table 36.2 Agents Reported to Induce Seizures

Intoxication from treatment with tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs) has led to generalized tonic–clonic seizures at therapeutic levels in approximately 1% of the patients (98). Because desipramine is believed to have a lower risk for precipitating seizures than other drugs in this class, the agent is preferred in patients with known epilepsy (99). Physostigmine may reverse the neurologic manifestations of TCA reactions; however, because it may also cause asystole, hypotension, hypersalivation, and convulsions, this agent should not be used to treat TCA-induced seizures. Benzodiazepines are preferred as the initial treatment. The combination of clomipramine with valproic acid may result in elevation of clomipramine levels with associated seizures (100).

Fluoxetine, sertraline, and other selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) have an associated seizure risk of approximately 0.2%. The SSRIs may have an antiepileptic effect at therapeutic doses (101). Fluvoxamine overdose has also been reported to provoke status epilepticus (102). When combined with other serotonergic agents or monoamine oxidase inhibitors, however, they may induce the “serotonin syndrome” of delirium, tremors, and, occasionally, seizures (103). Venlafaxine, a serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor, has emerged as a common cause of drug-induced seizures (104). There are reports of serotonin syndrome developing after concomitant use of antibiotics such as linezolid and the SSRI paroxetine, citalopram (105), and mirtazapine (106). Over-the-counter substances used in combination with SSRIs that have precipitated the serotonin syndrome include St. John’s wort (107).

Antipsychotic agents have long been known to precipitate seizures (97). Both the phenothiazines and the haloperidol have been implicated, but the potential is greater with phenothiazines, and seizures occur more frequently with increasing dosage (108). Clozapine, an atypical antipsychotic agent (dibenzodiazepine class) used for the treatment of intractable schizophrenia, also produces an increased incidence of seizures with increasing dosage (109). Lithium may also precipitate seizures (110). If reduction of dosage is not practical, phenytoin or valproate may be added; however, carbamazepine should be avoided because antipsychotic agents may induce agranulocytosis.

The use of theophylline and other methylxanthines may lead to generalized tonic–clonic seizures; rarely, patients may experience seizures with nontoxic levels of theophylline. Seizures resulting from overdosage are best treated with IV diazepam. Massive overdosage may induce hypocalcemia and other electrolyte abnormalities (111).

Lidocaine precipitates seizures, usually in the setting of congestive heart failure, shock, or hepatic insufficiency. General anesthetics, such as ketamine and enflurane, are also implicated (see section Central Anticholinergic Syndrome). Alfentanil is a potent short-acting opioid agent that may induce clinical and electroencephalographic seizures (112). Meperidine, pentazocine, and propoxyphene, among other analgesic drugs, infrequently cause seizures (113).

Verapamil intoxication may be associated with seizures through the mechanism of hypocalcemia, although hypoxia also may have a contributing role (114). Interestingly, other calcium channel blockers have not been reported to produce this adverse effect.

Many antiparasitic agents and antimicrobials, particularly penicillins and cephalosporins in high concentrations, are known seizure precipitants. It should be noted that some antibiotics, such as the fluoroquinolones, may lower the seizure threshold. Carbapenem antimicrobials also have significant neurotoxic potential, with meropenem perhaps having the lowest incidence (115,116). Lindane, an antiparasitic shampoo active against head lice (Pediculosis capitis), has a rare association with generalized, self-limited seizures; it is best to use another agent should reinfestation occur. Seizures have not been reported with permethrin, another antipediculosis agent.

Severe isoniazid intoxication involves coma, intractable seizures, and metabolic acidosis. Ingestion of >80 mg/kg of body weight produces severe CNS symptoms that are rapidly reversed with IV administration of pyridoxine at 1 mg per every 1 mg of isoniazid (117). Conventional doses of short-acting barbiturates, phenytoin, or diazepam are also recommended to potentiate the effect of pyridoxine (118).

Recreational Drug-Induced Seizures

Alldredge et al. (119) retrospectively identified 49 cases of recreational drug-induced seizures in 47 patients seen between 1975 and 1987. Most patients experienced a single generalized tonic–clonic attack associated with acute drug intoxication, but seven patients had multiple seizures and two had status epilepticus. The recreational drugs implicated were cocaine (32 cases), amphetamines, heroin, and phencyclidine; a combination of drugs was responsible for 11 cases. Seizures occurred independently of the route of administration and were reported in both first-time and chronic abusers. A total of 10 patients (21%) reported prior seizures, all temporally associated with drug abuse. Except for one patient who experienced prolonged status epilepticus causing a fixed neurologic deficit, most patients had no obvious short-term neurologic sequelae (119). Marijuana is unlikely to alter the seizure threshold (120) and is a common drug utilized by epileptics for self-medication. Patients with seizures who test positive for marijuana on toxicologic screening should be investigated for other illicit drugs and alcohol use.

Cocaine commonly gives rise to tremors and generalized seizures. Seizures can develop immediately following drug administration, without other toxic signs. Convulsions and death can occur within minutes of overdose. Pascual-Leone et al. (121) retrospectively studied 474 patients with medical complications related to acute cocaine intoxication. Of 403 patients who had no seizure history, approximately 10% had seizures within 90 minutes of cocaine use. The majority of seizures were single and generalized, induced by IV or “crack” cocaine, and were not associated with any lasting neurologic deficits. Most of the focal or repetitive attacks involved an acute intracerebral complication or concurrent use of other drugs. Of 71 patients with previous non–cocaine-related seizures, 17% presented with cocaine-induced seizures, most of which were multiple and of the same type as they had previously experienced (121).

The treatment of choice for recreational drug-induced seizures is lorazepam or clonazepam. Bicarbonate for acidosis, artificial ventilation, and cardiac monitoring are also useful, depending on the duration of the seizures. Urinary acidification accelerates excretion of the illicit drug. Chlorpromazine has also been recommended because it raised, rather than lowered, the seizure threshold in cocaine-intoxicated primates (122).

Acute overdose of amphetamine causes excitement, chest pain, hypertension, tachycardia, and sweating, followed by delirium, hallucinations, hyperpnea, cardiac arrhythmias, hyperpyrexia, seizures, coma, and death. Seizures are treated with benzodiazepines or, if long-term antiepileptic therapy is indicated, with phenytoin. Acidification of urine may enhance drug excretion.

Methamphetamine is a synthetic agent with toxic effects, including seizures, that is similar to those with amphetamine and cocaine (123). The amphetamine derivative (MDMA) stimulates the release and inhibits the reuptake of serotonin (5-HT) and other neurotransmitters, such as dopamine, to a lesser extent. Mild versions of the serotonin syndrome often develop, when hyperthermia, mental confusion, and hyperkinesia predominate (123). MDMA may also cause seizures in conjunction with rhabdomyolysis and hepatic dysfunction (124).

γ-Hydroxybutyric acid (GHB), or sodium oxybate, is an agent that is approved for use in patients with narcolepsy who experience episodes of cataplexy and excessive daytime sleepiness, It is also a popular agent among recreational drug users. GHB is a naturally occurring inhibitory substance in the human brain. GHB is believed to bind to GABAB and GHB-specific receptors. It blocks dopamine release at the synapse and produces an increase in intracellular dopamine. This is followed by a time-dependent leakage of dopamine from the neuron. Its abuse potential is secondary to its ability to induce a euphoric state, hallucinations, and relaxation without a hangover effect. Additional effects of increased sensuality and disinhibition further explain the popularity of the agent. Abusers will often ingest sufficient quantities to lead to a severely depressed level of consciousness. It is not uncommon to observe seizures in these cases. With acute overdose, patients have experienced delirium and transient respiratory depression, which can be fatal (125). The toxicity of GHB is dose dependent and can result in nausea, vomiting, hypotonia, bradycardia, hypothermia, random clonic movements, coma, respiratory depression, and apnea. Deaths involving solely the use of GHB appear to be rare and have involved the “recreational abuse” of the drug for its “euphoric” effects. Combining GHB with other depressants or psychoactive compounds may exacerbate its effects. GHB abuse frequently involves the use of other substances, such as alcohol or MDMA (126).

CENTRAL ANTICHOLINERGIC SYNDROME

Many drugs used as anesthetic agents and in the intensive care unit may cause seizures. Although a discussion of each agent is beyond the scope of this chapter, we review the central anticholinergic syndrome (127), a common disorder associated with blockade of central cholinergic neurotransmission, whose symptoms are identical to those of atropine intoxication: seizures, agitation, hallucinations, disorientation, stupor, coma, and respiratory depression. Such disturbances may be induced by opiates, ketamine, etomidate, propofol, nitrous oxide, and halogenated inhalation anesthetics, as well as by such H2-blocking agents as cimetidine. An individual predisposition exists for central anticholinergic syndrome that is unpredictable from laboratory findings or other signs. The postanesthetic syndrome can be prevented by administration of physostigmine during anesthesia.

OTHER SEIZURE PRECIPITANTS

Heavy metal intoxication, especially with lead and mercury, is a well-known seizure precipitant. Ingestion of lead from paint and inhalation of lead oxide are specific hazards among young children. Hyperbaric oxygenation provokes seizures, possibly as a toxic effect of oxygen itself. Some antineoplastic agents, such as chlorambucil and methotrexate, precipitate seizures. Table 36.2 lists other agents reported to induce seizures (128).

Increasingly utilized prophylactically and as alternative medicine, many herbs and other alternative treatments may increase the risk for seizures (129). This may be through intrinsic proconvulsive effects of contamination by heavy metals. These include cyanobacteria (aka spirulina, blue–green algae), ephedra (ma huang), Ginkgo biloba, pennyroyal, primrose oil, sage, star anise, star fruit, and wormwood. In addition, many herbs may have an effect on AED concentrations via the cytochrome P450 and P-glycoprotein systems.

More recently, there has also been concern that seizures may also be induced following consumption of energy drinks and supplements. It has been proposed that large consumption of compounds rich in caffeine, taurine, and guarana seed extract may provoke seizures (130). With the large consumption of energy drinks around the world, there is concern that there may be underestimation of the potential effects to induce seizures. Discussions also infer that the high intake of caffeine may induce sleep deprivation, or the concomitant higher consumption of alcohol with energy drinks may also be precipitating factors inducing seizures (131).

ECLAMPSIA

A condition unique to pregnancy and puerperium, eclampsia is characterized by convulsions following a preeclamptic state involving hypertension, proteinuria, edema, and coagulopathy, as well as headache, drowsiness, and hyperreflexia. Eclampsia is associated with a maternal mortality of 1% to 2% and a rate of complications of 35% (132). In the United States, magnesium sulfate is the chosen therapy, whereas in the United Kingdom, such conventional AEDs as phenytoin and diazepam are used (133,134). The antiepileptic action of magnesium sulfate is accompanied by hypotension, weakness, ataxia, respiratory depression, and coma. The recommended therapeutic range is 1.8 to 3.0 μmol/L; however, weakness and ataxia appear at 3.5 to 5.0 μmol/L and respiratory depression at 5.0 μmol/L (135). Kaplan et al. (136) argue that magnesium sulfate is not a proven AED; even at therapeutic levels, 12% of patients continued to have seizures in one study (137). The use of magnesium sulfate or conventional AEDs for preeclamptic or eclamptic seizures remains controversial. Because eclamptic seizures are clinically and electrographically indistinguishable from other generalized tonic–clonic attacks, the use of established AEDs, such as diazepam, lorazepam, and phenytoin, is recommended (136). In a randomized study of 2138 women with hypertension during labor (138), no eclamptic convulsions occurred in women receiving magnesium sulfate, whereas seizures were frequent with phenytoin use. Methodologic problems, however, involved the route of administration of the second phenytoin dose after loading and the low therapeutic phenytoin level at the time of the seizure.

Magnesium sulfate has a beneficial effect on factors leading to eclampsia and can reverse cerebral arterial vasoconstriction (139). By the time a neurologist is consulted, however, the patient will have received magnesium sulfate and will typically require additional AED treatment to control the seizures.

MALIGNANCY

Mechanisms for induction of seizures in patients with cancer include direct invasion of cortex or leptomeninges, metabolic derangements, opportunistic infection, and chemotherapeutic agents (140). Limbic encephalitis is a paraneoplastic syndrome seen in patients with small cell carcinoma, ovarian cancer commonly teratomas, germ cell tumors of the testes, or, less commonly, Hodgkin disease. Patients usually present with amnestic dementia, affective disturbance, and sometimes a personality change. During the illness, both complex partial and generalized seizures may occur. Paraneoplastic limbic encephalitis associated with anti-Hu (antineuronal nuclear antibody type 1) antibodies may present with seizures and precede the diagnosis of cancer (141). If the etiology of new-onset seizures is not defined in a patient with known cancer, frequent neuroimaging studies should assess the individual for metastatic disease. Chapter 33 details other paraneoplastic disorders that can present with seizures, including anti-NMDA receptor encephalitis.

Opsoclonus–myoclonus syndrome (myoclonic infantile encephalopathy) occurs most frequently in young children (mean age, 18 months). Approximately half of the cases have been reported in patients with neuroblastoma, but only approximately 3% of all neuroblastoma cases are complicated by the syndrome. Opsoclonus–myoclonus syndrome has been reported with carcinoma, including breast, ovarian, and small cell lung cancer, but occurs idiopathically as well. Because the idiopathic and paraneoplastic syndromes are indistinguishable clinically, opsoclonus–myoclonus syndrome should always prompt a search for neuroblastoma in children and these other cancers in adults. Symptoms respond to steroid or immunosuppressive therapy. In the majority of cases, successful treatment of the neuroblastoma or surgical resection of the primary cancer may lead to remission; however, the syndrome may reappear with or without tumor recurrence (142).

Finally, chronic treatment with nonhepatic metabolized AEDs including levetiracetam and gabapentin avoid drug interactions that may reduce the efficacy of chemotherapeutic agents.

VASCULITIS

Seizures as a manifestation of vasculitis may occur as a feature of encephalopathy, as a focal neurologic deficit, or in association with renal failure (143). The incidence of seizures increases with the duration and severity of the underlying vasculitis (144) and ranges from 24% to 45% (145). The relationship of the seizure disorder to the underlying disease may not always be clear, however. A confounding feature of AED therapy is the occurrence of drug-induced systemic lupus erythematosus (146

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree